Context

High quality health services require health professionals who have up-to-date skills and expertise, and are trained to be 'fit for purpose' for the work context. Allied health professionals (AHPs) working in rural and remote areas require unique skills. For example rural and remote AHPs frequently work in interprofessional teams, have greater work responsibility, less management support, reduced access to professional support structures, and deliver services across broader clinical areas to more culturally diverse populations than AHPs in metropolitan areas1-4. Establishing competencies for practice is one way of ensuring health care delivered by AHPs in rural and remote areas meets the high demands of their work, and that the attainment of these skills is recognised.

Competency and health

While the exact definition and usage of the term is contested, competency can be broadly defined as 'the knowledge, skills, ability and behaviours that a person possesses in order to perform tasks correctly and skilfully'5,p198. Recently there has been substantial focus on identifying competencies in health, both in Australia and internationally6,7. This is driven by a range of current and predicted challenges in the delivery of health care, particularly in remote and rural Australia6. Competencies are gaining prominence in health as means to increase both the quality and efficiency of health care services.

Competency frameworks serve many purposes in the delivery of quality health care. They are frequently employed as a tool to determine staff skills against the requirements of a position. They are also used to support staff development, as a tool to facilitate individual performance review, and to identify the ongoing professional development needs of individual employees8. At the organisational or institutional level, competency frameworks allow for the identification of skills and knowledge necessary to achieve an organisation's strategic agenda8. In terms of health management and leadership, Baker suggests that most importantly competency frameworks 'provide a language for talking more precisely about leadership knowledge and skills... [they] offer a way to deepen current conversations about the specific knowledge and skills necessary for leaders'8,p55, and provide a mechanism for measuring these.

Identifying competencies also has the potential to allow for the development of new work roles in health and increased efficiency of the healthcare workforce. Job re-design that includes using skilled workers in roles beyond the traditional scope of their work, is seen as one way of addressing future challenges in heathcare delivery6,9. Allied health assistants in rural and remote areas working under the supervision of AHPs are an example of this; they have the potential to increase work efficiency by increasing caseload throughput10.

WA Country Health Service

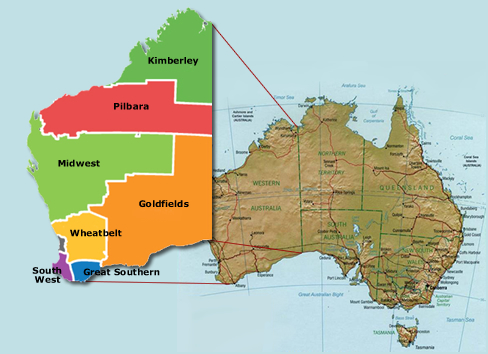

The WA Country Health Service (WACHS) is the state government provider of health and allied health services to rural and remote Western Australia (Fig1)11. The WACHS employs both base-grade and senior-level AHPs. In general, senior AHPs are charged with higher duties, which may include an advanced clinical role, the management and planning of service delivery, staff management and various other context specific duties. In WACHS, senior AHPs are occasionally line managed by AHPs of the same discipline working in a senior management role; however, more frequently this is by a manager with a different professional background. Senior AHPs in the areas of audiology, dietetics, occupational therapy, podiatry, physiotherapy, social work and speech pathology (excluding mental health and aged care), including vacant positions, are approximately 103 full time equivalent (FTE) of the WACHS workforce (pers. comm.; Human Resource Information System, Western Australian Department of Health; 16 May 2008). As a way to support these senior AHPs, WACHS aimed with this project to articulate in detail the competencies required by these professions. It was anticipated that the competencies could inform a range of strategies to enhance support for this workforce.

Figure 1: WA Country Health Service (WACHS) health regions in Western Australia.

Issue

Aim and scope of project

The aim of the Senior Allied Health Competencies Project was to develop a competency tool for senior allied health practitioners within WACHS. The primary target was AHPs from a core group of disciplines, including audiology, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, speech pathology, social work, podiatry and dietetics.

Drawing on the Skills for Health project in the UK12, the project team conceptualised the competencies necessary for rural and remote allied health practice as including three intersecting broad domains (Fig2): generic competency; professional competency and technical competency.

Figure 2: Conceptual model of rural and remote allied health competency areas.

Generic competency includes skills shared by all those within a health organisation and are not specific to health service provision roles (eg leadership and management, communication and interpersonal skills). Professional competency refers to skills shared by those in a healthcare role that are required by all health professionals or a specific subset (eg allied health competencies, and health professional competencies). Technical competeny describes skills relevant to a specific context, setting or patient group, and may include profession-specific competencies, specialty specific competencies or program-specific competencies. This includes profession-specific clinical competencies which are generally specified on a discipline-specific basis by professional associations, governing boards or program leadership organizations (examples13,14).

While alluding broadly to all domains of practice, this project is primarily focussed on professional competency necessary for rural and remote allied health practice across a range of professions. By its nature there is some overlap among the competency domain areas. Because of this, and because there are currently no existing generic competencies that exist for AHPs in WACHS, the potential was anticipated for rural and remote AHPs to identify generic competencies they believed were important to their role. The competency tool was intended to be used to identify the learning and developmental needs of senior staff, including areas of strength and proficiency. The framework was designed to be used either by individual AHPs for self-assessment, with peers or with line managers in the performance development process.

Project steps

The purpose of this project was consistent with a quality assurance (QA) endeavour, and carried minimal risk to participants, had voluntary participation, and protected participants' privacy. Exemption from formal ethical review was initially sought from and granted by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee on the basis of QA. Institutional ethical approval was provided by WACHS. A small project working group was established to advise and support the project officer on aspects of project development and management (eg project planning and methodology, monitoring progress, project promotion, and participant recruitment). These preliminary steps were followed by two substantive project stages: a formal literature review, and the development and refinement of the competencies via a Delphi review process.

Literature review: A review of the available literature was undertaken to identify potential competencies and competency frameworks in health management, with particular reference to the allied health field. The literature review aimed to identify existing competency frameworks for senior rural and remote AHPs, and in the absence of these to identify other competency frameworks with applicability to senior rural and remote AHPs.

Peer reviewed and non-peer reviewed databases were searched, including: Cochrane Library; Medline; and ProQuest Health and Medicine Complete. A Google web search was also undertaken to identify non-published material available on the world wide web. WACHS job description forms for senior allied health positions, and professional standards available on Australian allied health professional association websites were also reviewed.

A number of competency frameworks in health were identified. These fell broadly into three categories: multidisciplinary, clinical, and rural and remote. The multidisciplinary frameworks (examples14,15) sought to describe the necessary workplace competencies of a broad range healthcare professionals, across a range of professional levels and stages of career development.

Clinical frameworks described the clinical skills required of practitioners in a specific clinical context. These included: discipline specific frameworks (examples16-19) which described the competencies required of allied health practitioners in a specific discipline across a range of professional levels and stages of career development; entry to practice frameworks (examples13,20) which described the discipline specific clinical skills required of entry to practice practitioners, and generally supported the transition from student to professional; and condition or program specific frameworks (examples14,21-24) which described the competencies required of health professionals working in specific program areas or with specific conditions.

A single rural and remote competency framework was identified25. This framework described the skills required of community health staff working in a Scottish rural and remote context at a range of professional levels. While relevant identified competency frameworks were used to inform the project at this stage, no materials found captured the role of senior allied health staff within WACHS. However, thematic analysis of identified competency frameworks reflected a series of recurring key themes that contributed to the development of our senior allied health competency model. The themes included:

- management skills

- human resources

- leadership skills

- health and safety

- clinical practice

- ethics and professional practice

- policy

- workforce planning

- strategic planning/ governance

- education and professional development

- technology

- cultural awareness

- research and evaluation

- financial and physical resource management.

Competency development and refinement: Prior to the commencement of this project, a draft bank of competencies had been developed informally by senior AHPs within the WACHS Allied Health Reference Group (AHRG). These competencies were combined with results of the literature review in order to develop a draft competency framework.

A modified Delphi review process was undertaken with rural and remote senior level AHPs and managers to refine and reach agreement on competencies relevant to senior AHPs within WACHS. Delphi is a technique used to reach consensus on a particular subject or problem from a large number of often geographically dispersed groups26. Stakeholders are asked to provide feedback on the particular subject or problem, the original subject or problem is reviewed and further developed, then it is returned to stakeholders for further feedback. This review process is repeated several times until consensus is reached26.

The project included three phases of modified Delphi review. First, feedback from allied health managers and senior allied health staff from occupational therapy, physiotherapy, speech pathology, social work and dietetics, was sought from each of the WACHS regions. Respondents ranked the appropriateness and importance of each of the initial 109 competencies to the role of a senior AHP on a three-point scale (1 = highly appropriate/important, to 3 = not relevant to role/low priority). Open-ended questions prompted respondents to identify other areas requiring development. Feedback was received from 34 respondents.

With the exception of one item relating to financial skills, the mean response scores were between 1 and 2, indicating general agreement on the appropriateness and importance of each competency. Based on the feedback received the draft framework was refined to reflect the hierarchy as ranked by respondents, and then consolidated to reduce areas of repetition (respondents valued a short document for ease of practical administration). As well as the previously mentioned item relating to financial skills, two further domain areas that scored relatively poorly (research and evaluation, and consumer involvement in services) were consolidated and abbreviated to reflect their relatively low ranking (although overall these were considered relevant to the role). At the conclusion of this round there were 107 competencies.

Focus group interviews27 were used in the second Delphi round to allow in-depth interrogation of the refined competencies. A purposive sampling strategy included key informants who had provided in-depth feedback during the first Delphi round and other AHPs recruited to encompass each of the target disciplines and WACHS regions. Sixteen participants took part in four focus groups, either face to face or via videoconference. Focus group interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min. A guided interview schedule was used to examine the relevance, appropriateness and utility of the framework as a whole, domain areas, each individual competency, and format and layout. Again, feedback was consistently positive about the document content. Participants again highlighted the need for a succinct document and, as a result, a number of competencies were again prioritised and consolidated (eg a domain on 'human resources' was incorporated as a sub-domain of 'professional skills').

The third and final Delphi round involved the circulation of the developing framework to the AHRG, WACHS population health directors and managers, and all senior AHPs within WACHS for review via organisational email distribution lists. Fourteen responses were received. Feedback was consistently positive. Comments were received on language, wording, grammar and clarity and these comments were incorporated in the final draft document. Following final proofreading the competency framework was disseminated to senior allied health staff in WACHS for final endorsement.

Rural and Remote allied health competencies - senior professional framework

The final Rural and Remote Allied Health Competencies - Senior Professional (RRAHC-SP) framework consists of 88 competencies under 33 sub-domain and 8 overarching domain areas (Fig3). The complete tool is available (http://www.wacountry.health.wa.gov.au/alliedhealthcompetencies).

Figure 3: The domain and sub-domain areas of the rural and remote allied health competencies - senior professional.

To assist in using the RRAHC-SP, five cyclical steps were recommended. First, the competencies most relevant to current work role are identified (Fig4). Second, the level of proficiency in these competencies is rated as emergent, developing, refining or highly developed. These are rated either by an individual, a peer or a manager. This allows for the identification of priority competency areas that in the third step are listed in the summary of priority competencies table within the document. Fourth, these priority areas are integrated into a learning plan (eg performance management plan, supervision plan, mentoring plan, individual learning plan, departmental/team learning plans). The fifth and final step is to operationalise the plan, and to reflect and review progress on a regular basis.

Figure 4: Example of a service planning competency with work relevancy and competency ranking scale.

Lessons learned

The primary outcome of this project has been the completion of the RRAHC-SP framework. The findings of the literature review suggest this is the first competency tool developed for senior level AHPs in the rural and remote context. Similarly this is the first attempt known to the authors to document the unique roles of this workforce, and to identify common competencies across a core of allied health professions. Competencies for AHPs are in their infancy in Australia, if not internationally, and to the authors' knowledge have not been addressed for rural and remote AHPs previously. While these competencies are designed to meet the organisational requirements of WACHS, we believe they will have some currency for AHPs in other rural and remote areas of Australia and in similar health service environments in other countries, and may contribute to further discussion on competencies.

The RRAHC-SP has been designed to have multiple applications for AHPs in WACHS. Individually or with peers, the tool may be used by AHPs to identify areas of work proficiency and need in developing a continuous professional development plan. The framework may also be used in organisational performance development processes. This has particular utility in situations where senior AHPs are managed by people from different professional backgrounds. Finally, the tool can be used broadly to identify common areas of development need across multiple professions in the AHP workforce, enabling WACHS to develop targeted training. There is potential to extend this function as the RRAHC-SP aligns with elements of development frameworks used in medicine28 and currently under review in WACHS for nurses. This allows for future identification and mapping of multi-professional competency requirements, and allows for the development of strategies to meet these broad competency training needs across the health sector.

Conclusion

The use of competency frameworks is an emerging area in the health arena. To date, little work has been performed on the inter-professional competencies of AHPs, and less on those in the Australian rural and remote context. This project has developed a competency framework to guide the clinical management and leadership role of senior AHPs in rural and remote Western Australia.

The RRAHC-SP framework has been designed to support a range of life-long learning strategies. It provides a framework for senior AHPs for use in planning their personal/professional learning and developmental needs, and it can be applied to a range of scenarios. While the primary focus of this project was to increase quality in allied health services by increasing competency and support of AHPs, using this tool to identify cross-profession training needs potentially allows WACHS to provide cost-effective, targeted training across its broader workforce.

The next step is the implementation of the RRAHC-SP framework. A multi-level implementation strategy is planned and will include: the dissemination of the tool throughout WACHS; the incorporation of the tool into the orientation and induction of all new senior AHPs; and linking the tool to performance development, clinical supervision and continuing professional development activities. Once this is done WACHS can commence developing relevant training and development programs to respond to identified priority areas. Future steps will be to evaluate the reach, uptake, utility and outcomes of the RRAHC-SP framework in supporting the developmental needs of senior level AHPs. Developing similar competency frameworks in other rural and remote health workforces, for example targeting entry level AHPs, is an area of ongoing work.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge participants from WA Country Health Services, in particular allied health professionals, the Allied Health Reference Group, and the managers who participated in survey and focus groups. Also acknowledged are Aasta Abbot and Dawn Logan who were original members of the steering group, and Ann Larson who provided feedback on an earlier draft of the manuscript. The Combined Universities Centre for Rural Health is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing.

References

1. Bent A. Allied health in Central Australia: Challenges and rewards in remote area practice. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 1999; 45: 203-212.

2. Grimmer K, Bowman P. Differences between metropolitan and country public hospital allied health services. Australian Journal of Rural Health1998; 6(4): 181-188.

3. Sheppard L. Work practices of rural and remote physiotherapists. Australian Journal of Rural Health2001; 9: 85-91.

4. Wakerman J. Rural and remote public health in Australia: Building on our strengths Australian Journal of Rural Health 2008; 16(2): 52-55.

5. Whelan L. Competency assessment of nursing staff. Orthopaedic Nursing 2006; 25(3): 198-204.

6. Productivity Commission. Australia's health workforce: research report. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005.

7. National Health Workforce Taskforce. Education and training: core competencies framework for the health workforce. Melbourne, VIC: NHWT, 2008.

8. Baker R. Identifying and assessing competencies: a strategy to improve healthcare leadership. Healthcare Papers 2003; 4(1): 49-58.

9. Duckett SJ. Health workforce design for the 21st century. Australian Health Review 2005; 29(2): 201-210.

10. Goodale BJ, Spitz S, Beattie NJ, Lin IB. Training rural and remote therapy assistants in Western Australia. Rural and Remote Health 7: 774. (Online) 2007. Available: www.rrh.org.au (Accessed 30 March 2009).

11. Department of Health Western Australia. WA Country Health Service. (Online) 2006. Available: http://www.wacountry.health.wa.gov.au/ (Accessed 20 October 2008).

12. Skills for Health. Skills for health. (Online) 2008. Available: http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/page/competences/completed-competences/list (Accessed 20 October 2008).

13. Speech Pathology Australia. Competency-Based Occupational Standards (CBOS) for speech pathologists entry level. (Online) 2001. Available: http://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/library/CBOS%20Entry%20Level%202001.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

14. Australian Physiotherapy Association. Musculoskeletal physiotherapy professional practice standards. (Online) 2003. Available: http://physiotherapy.asn.au/images/Document_Library/Standards/2003%20musculoskeletal%20standards.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

15. Department of Human Services Victoria. Competency standards for health and allied health professionals in Australia. (Online) 2005. Available: http://www.health.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/306195/core_clinical_skills_mapping.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

16. Speech Pathology Australia. Principles of practice. (Online) 2001. Available: http://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/library/PrinciplesOfPractice.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

17. Australian Physiotherapy Council. Australian standard for physiotherapy. (Online) 2006. Available: http://www.physiocouncil.com.au/australian_standards_for_physiotherapy (Accessed 20 October 2008).

18. Australian Association of Social Workers. Practice standards for social workers, Australian Association of Social Workers. (Online) 2003. Available: http://www.aasw.asn.au/adobe/publications/Practice_Standards_Final_Oct_2003.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

19. Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Competency standards for pharmacists in Australia. (Online) 2003. Available: http://www.psa.org.au/site.php?id=643 (Accessed 20 October 2008).

20. Australian Association for Occupational Therapists. Australian competency standards for entry-level occupational therapists. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Association for Occupational Therapists, 1984.

21. National Mental Health Education and Training Advisory Group. National practice standards for the mental health workforce. (Online) 2002. Available: http://www.aasw.asn.au/adobe/publications/mental/MH_endorsed_prac_standards.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

22. Australian Physiotherapy Association. Sports physiotherapy professional practice standards. (Online) 2003. Available: http://physiotherapy.asn.au/images/Document_Library/Standards/2003%20sports%20standards.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

23. Queensland Health and Griffith University. Audit of the training and education needs of staff working in community based rehabilitation in Queensland. (Online) 2006. Available: http://www.health.qld.gov.au/qhcrwp/docs/comp_audit_summary.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

24. Australian Association of Occupational Therapists. Australian Competency Standards for Occupational Therapists in Mental Health. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Association for Occupational Therapists, 1999.

25. Skills for Health. Map of competences for remote and rural healthcare. (Online) 2004. Available: http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/remote_and_rural_healthcare_competences.pdf (Accessed 20 October 2008).

26. Turoff M, Linstone H. The Delphi method: techniques and applications. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1975.

27. Kitzinger, J. Focus groups with users and providers of health care. In: C Pope, N Mays (Eds). Qualitative research in health care. Bristol: BMJ Books, 2000.

28. Confederation of Postgraduate Medical Education Councils. Australian curriculum framework for junior doctors. (Online) 2006. Available: http://curriculum.cpmec.org.au/Curriculumv2.1_A3.pdf (Accessed 30 March 2009).