Introduction

Disparity between health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and the broader Australian population is well recognised1-4. A contributing factor to this situation is the lack of access to culturally safe primary health care services5. Any effort to close this gap must acknowledge the significant contribution that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers (Indigenous health workers – IHWs) make to this process and support the development of policies and strategies that strengthen and sustain this integral component of the Australian health workforce6,7.

In 2012 a number of significant events occurred that were vital in enhancing recognition of the IHW role and strengthening the IHW workforce. First, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practice Board of Australia was established to regulate and register a new profession, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioner (ATSIHP). The role of IHW was integrated into this new profession7. This marked an important recognition of the contribution made by the profession to the Australian health workforce8. Second, in recognition of the need to further develop the IHW workforce, the Australian Government produced Growing our future: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Project final report6. Recommendation 27 of the report endorsed the requirement to help the existing workforce to meet the minimum qualification requirements for registration as an ATSIHP, through recognition of prior learning and/or further education6.

In June 2013, Health Workforce Australia contracted James Cook University (JCU) and its consortia partners (Technical and Further Education (TAFE) Queensland North Cairns; Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services Council, Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council, Mount Isa Centre for Rural and Remote Health, Townsville Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporation for Health Services and Apunipima Cape York Health Council) to implement the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Skills Recognition and Up-skilling Project over a 2-year period for north Queensland and Western Australia9. Due to changes within Health Workforce Australia and the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services Council, the project was refined to cover north Queensland. The project aimed to deliver skills assessment, recognition of prior learning and/or upskilling training to eligible IHWs to assist them to qualify for a Certificate IV in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care Practice. This brief commentary will share the process of implementation of this project, highlighting some of the key issues experienced and the subsequent lessons learned.

Context

The IHW profession has a long, proud and complex history in northern Australia. Northern Australia is characterised by a dispersed and diverse population who live in regional, rural and remote locations. Populations across rural and remote settings are often culturally diverse and relatively small, creating challenges for health service delivery. IHWs who operate in this challenging environment deal with complex and acute clinical scenarios, often involving family and friends. Therefore it is essential that ongoing professional training is available to support the IHW role.

Approximately 200 IHWs expressed an interest in undertaking the upskilling program – far beyond the scope of the 2-year project. This demonstrated a clear need for such programs to assist IHWs to develop personally and professionally to work within this challenging environment and to help ensure sustainable health services into the future. Students who applied to undertake the upskilling program came from locations that covered a large geographical area. Students travelled from as far north as the Torres Strait and Cape York, as far south as Rockhampton and Woorabinda and as far west as Mount Isa. Figure 1 illustrates the final number of students selected for the upskilling program and the Queensland communities in which they were located.

Training was delivered by and under the auspice of TAFE Queensland North Cairns. TAFE worked collaboratively with the Clinical Skills Unit team, College of Medicine and Dentistry at JCU to deliver the clinical skills sessions by way of residential blocks. There were three cohorts of students (approximately 19 students per group) throughout the duration of the project and each cohort attended a 2-week residential block where clinical skills training, lectures and assessments were conducted.

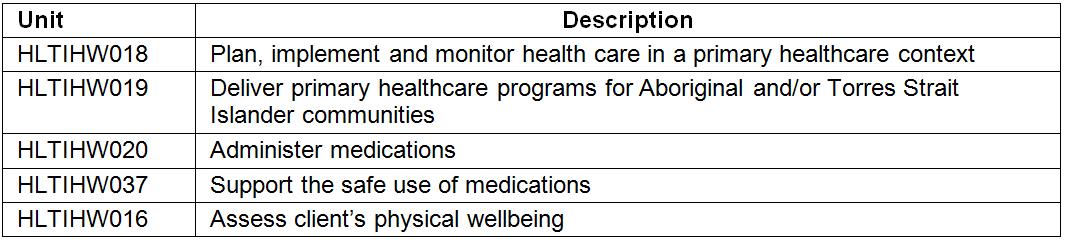

The upgrade practice skill set training that was delivered included five core units (Table 1), which were identified by the Community Services and Health Industry Skills Council as the training required of IHWs to be eligible for registration with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practice Board of Australia under a grandparent clause10.

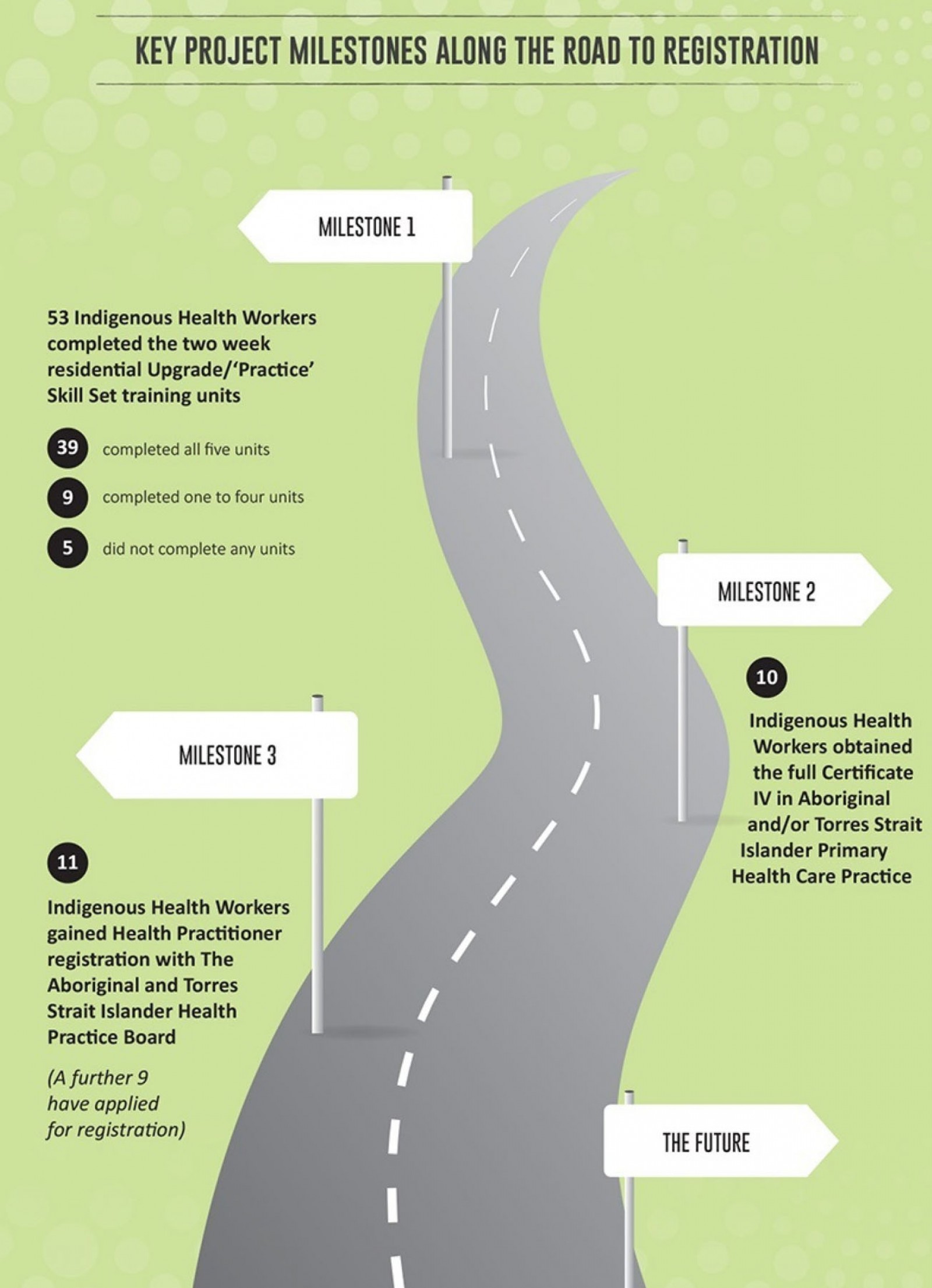

Despite a series of challenges and unexpected events, which will be discussed next, the project achieved some significant milestones as depicted in Figure 2. There are still approximately 150 names of IHWs on the waitlist for upskilling training.

Table 1: Five units of the upgrade ‘practice’ skill set

Figure 1: Distribution of students by community.

Figure 1: Distribution of students by community.

Figure 2: Key project milestones along the road to registration.

Figure 2: Key project milestones along the road to registration.

Issues

The project experienced a number of challenges, particularly during the establishment phase, that impacted on the project. First, the opportunities for training in Certificate IV Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care qualification in north Queensland was severely hampered with the closure of the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Education Program Aboriginal Corporation at the end of 2012. This was compounded by the upgrading of the national Health Training Package and new release of Certificate IV in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care Practice (HLT40213), for which TAFE was required to spend a considerable amount of lead time developing new training resources.

Second, the project team faced an enormous task given that the ATSIHP role and registration process was relatively new in north Queensland. In 2012, only 10 ATSIHPs were employed in Queensland, with most of these based in south-east Queensland11. As a result of this role being relatively new, there was uncertainty about the scope of practice, the appropriate utilisation of the ATSIHPs within the current primary healthcare system and the process for registration. This was compounded by a history of underutilisation and undervaluing of the IHW workforce which continues to diminish the efforts of IHWs to improve health standards in their communities and help close the gap4.

There was also little uniformity in IHW training, roles and job descriptions in Australia12,13 and the role and scope of practice of the IHW was often poorly understood by the community and also by a significant number of health professionals4. This made it necessary to cater for diverse educational needs in each cohort, which was challenging. Some IHWs came with significant clinical skills whilst others were more skilful in advocacy and cultural translation or health promotion. Prior educational standards of individual IHWs in terms of language, literacy and numeracy (LLN) also impacted on their ability to progress successfully in the program.

Finally, because the project covered a large and diverse geographic area with a high proportion of IHWs living in rural and remote areas there were associated complexities and challenges with providing training; this is a common issue for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in rural and remote areas14,15. Some of these challenges include the cost of being away from family, work and community; and difficulty accessing learning materials and support due to unreliable internet and other infrastructure barriers.

Lessons learned

Evaluation

A course experience questionnaire was used to evaluate the program and students’ experience. Results showed that student satisfaction improved with each cohort: 65.5% for cohort 1, 90.32% for cohort 2 and 93.75% for cohort 3. Student feedback was also collected through TAFE evaluation forms and opportunistic feedback. Students reported that having quality clinical skills training, particularly within a simulation learning environment, with the opportunity to practice clinical skills, was the most beneficial aspect of the training. The opportunity to share and learn from each other was also identified by each cohort of students as an important success factor. Some students reported challenges in hearing and understanding content due to English being a second or third language.

A number of lessons were learned throughout the project, but five stand out. Firstly and foremost, there is a need to continue to recognise and promote understanding of the contribution that the IHWs and ATSIHPs make in providing sustainable healthcare services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in rural and remote Australia. Recognition and promotion of the role will help prevent undervaluing and underutilisation of this important role in the future and ultimately improve health outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

Another important lesson pertained to the selection process for enrolment into the upskilling project. Student selection and support were improved upon each time a new cohort of students commenced. It is recommended for future upskilling training that a comprehensive student selection process is undertaken, allowing sufficient time for screening, building relationships with IHWs and their employers, and for formulating a list of selection criteria by which students are assessed. Implementing these processes will provide more positive training outcomes.

The third lesson involved the value of working collaboratively between the vocational and educational training and university sectors. Working in partnership, TAFE Cairns and the Clinical Skills Unit, College of Medicine and Dentistry at James Cook University were able to deliver quality learning experiences for the IHWs enrolled in the upskilling project. Strategies utilised for delivering quality clinical education in a collaborative environment included regular collaborative meetings to explore innovative teaching strategies and enhanced simulation opportunities and a commitment to providing quality education. Benefits included sharing resources such as simulation equipment, access to clinical skills teaching staff, and access to lesson plans and learning activities. It is recommended that future training models should consider utilising the substantial capacities (both in the way of clinical expertise and infrastructure) within university departments of rural health, clinical schools and rural universities to support the training of ATSIHPs.

Equally as important as the collaborative relationship between TAFE Cairns and JCU were partnerships between higher education and the health industry. In addition to selecting the right applicants, significant effort was put into ensuring that both applicants and their employers understood the goals of the training and how it related to the new ATSIHP role and health practitioner registration. Time spent building stronger relationships with employers and employees will not only ensure more satisfied students and employers but also assist in bridging the gap between the higher education sector and the health industry to ensure that training is reflective of industry needs. Furthermore, building these relationships will promote understanding of the ATSIHP profession.

The final lesson involved the need to ensure flexible funding models that enable adequate learning support to be embedded in any future training projects. TAFE Cairns conducted an LLN assessment on the first morning of the final residential block. The results revealed that most students were below the necessary standard to complete Certificate IV level units. As a result, the teaching staff incorporated a number of learning support sessions during the 2-week residential block. This was particularly important in supporting students to complete the ‘administer medications’ unit where drug calculations was a large component. It is recommended that, in future, LLN testing should be conducted prior to students attending the residential training in order for learning support staff to develop and implement individualised learning support plans.

Conclusion

In this commentary we have shared a north Queensland experience of the somewhat new process of training and registering ATSIHPs in Queensland through accredited skills recognition and upskilling training. Despite a number of challenges and unexpected events, the region has benefitted from the opportunity to work collaboratively both within the higher education sector (TAFE and JCU) and with the health industry to strengthen the ATSIHP workforce in north Queensland.

The project identified a need for more skills recognition and upskilling training, with approximately 150 IHWs in north Queensland potentially interested. More work is required to determine the needs and aspirations of this group of IHWs, and to develop flexible funding models and training pathways that respond to this need.

There is no doubt that the journey along the road to registration for ATSIHPs has some way to go. Furthermore, the journey continues with regards to recognising the significant contribution that ATSIHPs make to the health of Australia. This project has identified some useful lessons for future upskilling training. Most significantly, there is a need for further training opportunities in this region, and this commentary advocates funding models that allow for flexible training models, such as the one demonstrated in this project between TAFE Cairns and JCU.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Jane Mills for her consultation and guidance in the planning of this article and acknowledge the financial support of the Australia Government through the former Department of Industry, Innovation, Climate Change, Science, Research and Tertiary Education and Health Workforce Australia, for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Skills Recognition and Up-skilling Project.