Introduction

It is well established that Australians living in rural and remote areas experience higher mortality, poorer mental health outcomes (as demonstrated by the higher suicide rate) and a higher prevalence of several chronic diseases than their metropolitan counterparts1. Likely contributors to this disparity have been documented in the literature. The costs of accessing essential services such as health, education and aged care in rural areas have been reported as two to ten times that demanded of urban residents2. Further, shortages of general practitioners, nurses, allied health professionals, support services, clinical trials and specialist follow-up in rural areas are well documented3. Education levels are substantially lower2, transport issues more severe4, and there is higher representation of vulnerable groups (eg Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people) in rural Australia5. Poor awareness of available support services4,6,7 due to limited exposure to them and hence limited awareness of their role and benefits8, combined with lower levels of mental health literacy9,10 and general health literacy11, may also explain why people living in rural areas are more reluctant than their urban-based counterparts to seek medical and mental health support.

In addition to structural/system-based and knowledge-related factors, there is emerging evidence that unique subcultural values and attitudes affect patterns of health-related support seeking in rural communities12-16. Examples of attitudinal barriers identified by previous research include stigma13,14,17-19, self-reliance20, concerns about confidentiality21 and reluctance to seek help from ‘newcomers’22. There is also emerging evidence to support long-held anecdotal beliefs that men face greater barriers to help-seeking than women. For example, Emery et al. interviewed rural men and women and highlighted the need to be perceived as ‘tough’ or ‘macho’ as a reason men are sometimes reluctant to seek help for symptoms of tumours (eg prostate and colorectal cancer)19. Other studies have also concluded that men face more negative attitudes towards mental health help-seeking23, for example due to stoicism, stigma and concerns about privacy24.

While these studies are useful in explaining how the ‘culture’ of rural communities contributes to rural health, to date, few studies have tested widely held assumptions in this field, in particular differences between barriers to help seeking for physical health versus mental health issues, or the assumptions about differences in perceived barriers between rural men and women in the context of seeking help for physical health issues. Increasing the knowledge about the barriers to help seeking, separately by gender, and the contexts in which they operate is a necessary first step to informing new strategies to reduce health disparities between urban and rural populations. In particular there is a need to increase access to interventions that address health and mental health issues in the early stages, when treatment is often least burdensome and most effective. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare gender-specific perceived barriers to support seeking, separately in relation to physical health and mental health, in a sample of rural South Australians. To the authors’ knowledge, it is the first study of this type.

Methods

Participants

In 2014, adults (≥18 years) from three rural and remote regions in South Australia (Eyre Peninsula, Riverland and Yorke Peninsula/Copper Coast) were randomly selected from the White Pages electronic phone directory (non-commercial) to participate in a computer assisted telephone interview (CATI) on their perceived barriers to seeking support from health professionals. These three regions were selected to capture diverse industries (including grain, livestock, grape, citrus production, fishing) and because they had sufficient populations for time-efficient sampling. Up to five attempts to individual telephone numbers were made before a non-response was recorded. Participants were randomly allocated to respond in the context of either a physical health scenario or a mental health scenario, as it was anticipated that the burden on participants of responding in reference to both contexts would be unacceptably high. People were selected from the general rural population because it was expected that if samples were collected from people who had already received diagnoses of mental or physical health disorders, they would hold different views to those rural people who had less experience with the health system. It was also hoped that the study would identify barriers that could be reduced to promote early intervention.

Measures

CATI introductory script: The scripts described below were used to set the context for the physical health and mental health scenarios at the beginning of each CATI. To minimise the chance of confusion, the script was repeated midway through each CATI to remind participants of the response context, and participants were free to seek clarification at any time during the interview. The physical health scenario was a slightly modified version of the scenario presented in the original Barriers to Help Seeking Scale (BHSS)25 while the mental health scenario was developed for the current study based on features of major depressive disorder, described in the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5)26. This mental health scenario was considered appropriate by two experienced mental health practitioners (KF and MJ) and the whole CATI script was pilot tested with a demographically compatible group, who confirmed that it made sense to them.

Physical health scenario: ‘Imagine that you begin to experience an unusual physical feeling in your body. This might be a persistent pain in your back or headaches. The pain is not so overwhelming that you can’t function. However, it continues for more than a few days and you notice it regularly.’

Mental health scenario: ‘Imagine that you have been feeling unusually down in recent times. You haven’t been sleeping well, seem to have lost interest in things that you used to enjoy and are having difficulty concentrating.'

The interviewer then continued with the following script (modified slightly from the original BHSS scale) in both scenarios: ‘You consider seeking help from a medical doctor or other healthcare provider. I am going to read out several reasons why you might choose not to seek help. Please consider each reason and decide how important it would be in keeping you from seeking help.’

Scenarios have been used in similar studies of help-seeking in general Australian27 and rural Irish populations23.

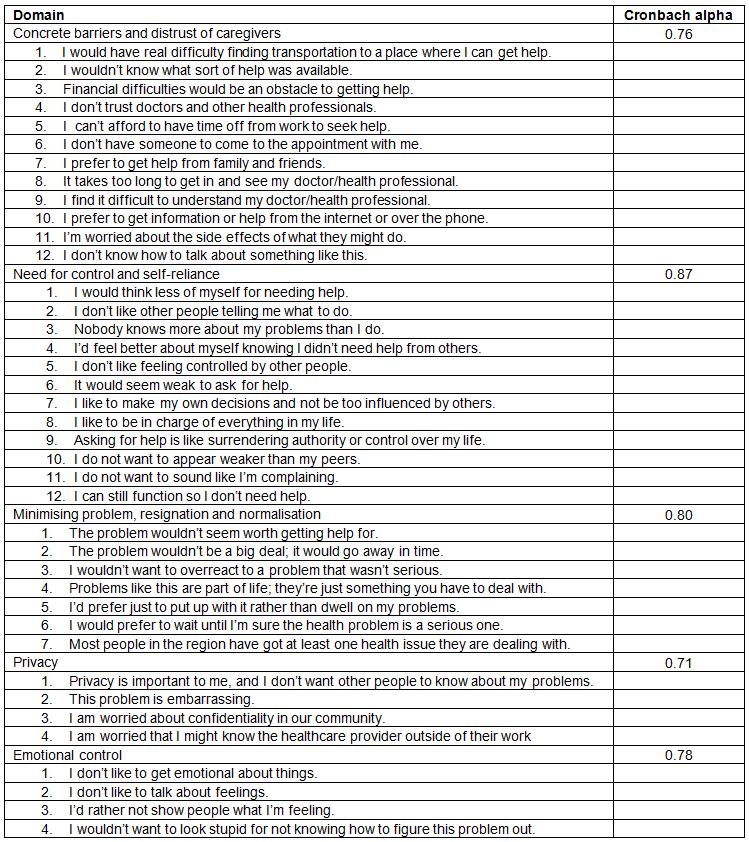

Barriers to help-seeking: The following domains were represented in the questionnaire, which was adapted from the BHSS25: ‘need for control and self-reliance’ (12 items), ‘concrete barriers and distrust of caregivers’ (12 items), ‘minimising problem, resignation and normalisation’ (7 items); ‘privacy’ (4 items) and ‘emotional control’ (4 items). Items 11 and 12 (Table 1) in the ‘need for control and self-reliance’ domain were added to the 10 items in this domain in the BHSS, while item 7 in the ‘minimising the problem, resignation and normalisation’ domain was added to the six items in this domain in the BHSS. The added items represent health-related attitudes that have emerged in the authors’ unpublished, qualitative research on barriers to help seeking among South Australian farmers and an author review of the literature. Item responses from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’) were averaged to form domain scores (higher scores representing stronger barriers to seeking support) with acceptable internal consistency (Table 1).

Education level: Highest education level was represented as follows: never attended, some primary school, completed primary school, some high school, completed Year 12 at high school, trade or diploma, university or other tertiary qualification.

Work status: Work status was represented as follows: self-employed, employed for salary or wage, unemployed, home duties, student, retired, unable to work.

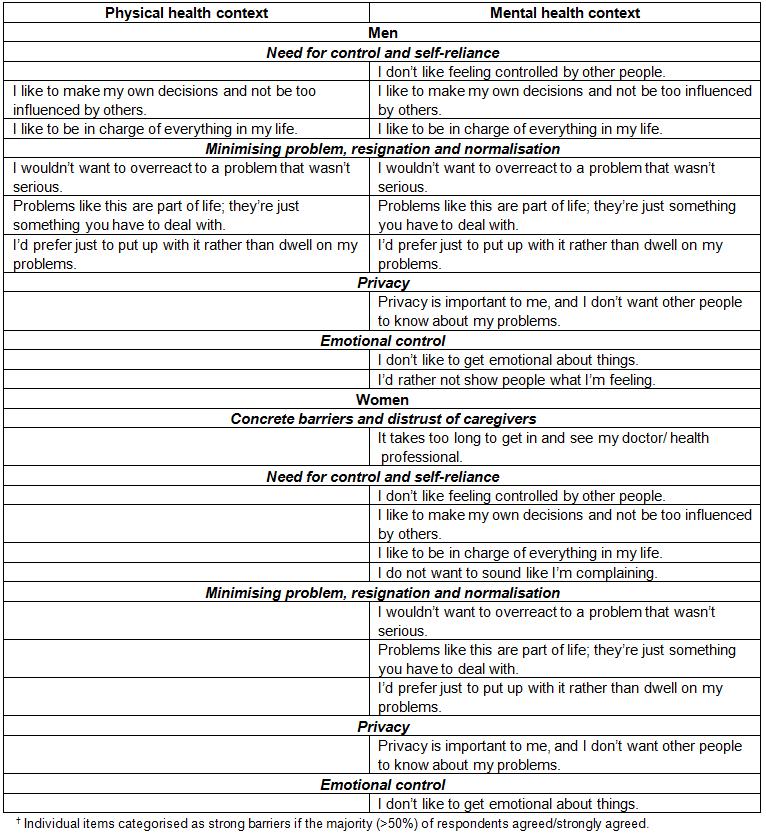

Table 1: Individual items, by domain, from the questionnaire, with internal consistency for each domain

Statistical analyses

Domain scores were normally distributed and therefore compared between the physical and mental health contexts using ANOVA or ANCOVA, separately in men and women. Candidate covariates (age and education level) were initially tested using first-order correlations. Age was unrelated to domain scores in both the mental health and physical health contexts, among both men and women, and so was not controlled for. However, education level was inversely correlated with most domains in the female sample, and so was subsequently controlled for using ANCOVA in the female sample (but not in the male sample).

As domain scores provide no absolute scale of barrier strength, the percentages of respondents who agreed (by indicating that they ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’) with the barrier represented by each item were calculated. Individual items were then categorised as strong barriers if the majority (>50%) of respondents agreed. Analyses were performed in Stata v12 (StataCorp; http://www.stata.com). Statistical significance was inferred at p<0.05.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (Application ID: 0000033418).

Results

Descriptive statistics/response rate

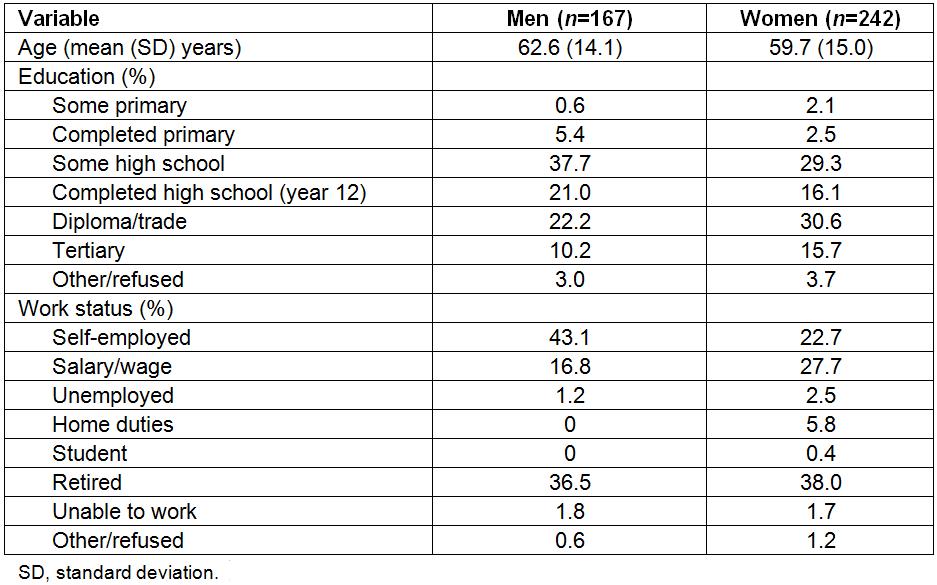

Four hundred and nine adults (average age=60.4±14.4 years) participated, 40% of those who answered the telephone and met the inclusion criteria. Approximately half of the participants were presented with the physical health scenario (n=206) and the remainder with the mental health scenario (n=203). Descriptive statistics for the sample are displayed in Table 2. The majority of men were self-employed (43.1%) or retired (36.5%), while a higher proportion of women than men worked for a wage. Over 50% of men and 60% of women had completed secondary school or higher. Only 2% reported that English was their second language.

To examine the representativeness of the sample, demographic characteristics were compared with the broader Australian population using representative population-based data collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics28,29. The study sample was older than the general adult population and comprised relatively fewer men, people with trade and/or tertiary qualifications and people who currently worked. The relatively high proportion of older participants may be attributable to sampling from the telephone directory and younger people’s preference for mobile phones30, for which numbers are rarely listed.

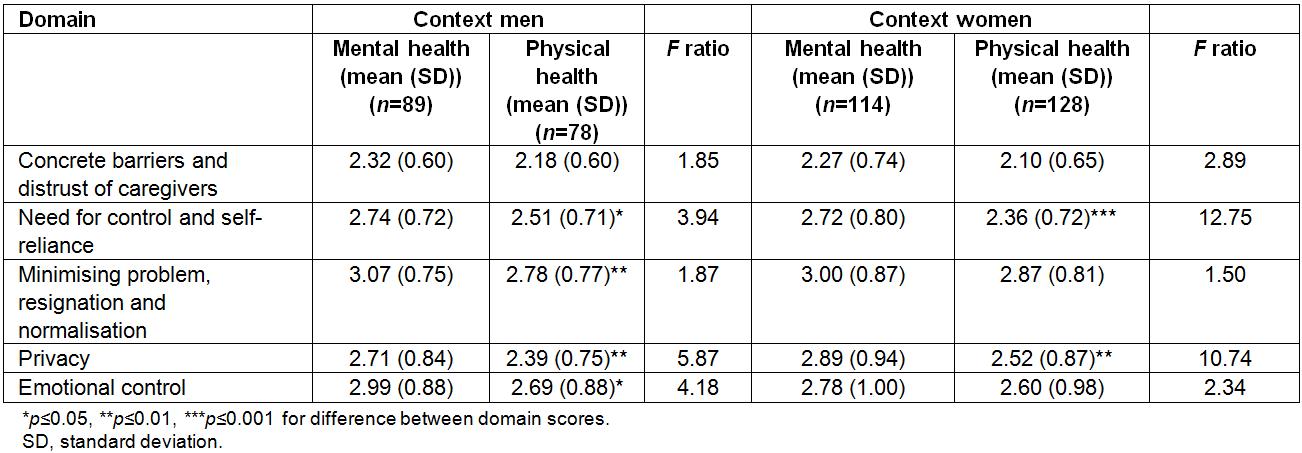

Among men, there were statistically significantly higher perceived barriers for the mental health scenario compared with the physical health scenario in the following domains: ‘need for control and self-reliance’, ‘minimising the problem, resignation and normalisation’, ‘privacy’ and ‘emotional control’ (Table 3). Among women, there were significantly higher perceived barriers for the mental health scenario in the following domains: ‘need for control and self-reliance’ and ‘privacy’. For each of these domains, the F ratios for comparing scenarios were negligibly different in unadjusted and adjusted (for education level) models: ‘need for control and self-reliance’ (unadjusted F=13.46 and adjusted F=12.75) and ‘privacy’ (unadjusted F=10.62 and adjusted F=10.74). These statistics indicate that, in the sample of females, education level explained very little of the observed differences between scenarios. There were no domains for which perceived barrier scores were higher in the physical health context than the mental health context, among men or women.

The item-level barriers that were strongly endorsed, separately by health context and gender, are summarised in Table 4. In the context of physical health, there were two strong item-level barriers in the ‘need for control and self-reliance’ and ‘minimising the problem, resignation and normalisation’ domains among men, and no strong barriers at the item level among women in any domains (Table 4). On the other hand, in the context of mental health, there were strong item-level barriers in all domains for both men and women. Gender-specific strong item-level barriers in the mental health context were, ‘It takes too long to get in and see my doctor/health professional’ (in the ‘concrete barriers and distrust of caregivers’ domain) among women, ‘I don’t want to sound like I’m complaining’ (in the ‘need for control and self-reliance’ domain) among women, and ‘I’d rather not show people what I’m feeling’ (in the ‘emotional control’ domain) among men.

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of the sample

Table 3: Comparisons of domain scores (mean ±SD) between the physical health and mental health contexts, stratified by gender

Table 4: Strong barriers at the item level†, separately in mental and physical health contexts

Discussion

The rural South Australians who participated in this study perceived more and stronger barriers to accessing support for a mental health condition than a physical health condition. The attitudinal barriers that were endorsed significantly more strongly by both men and women in relation to mental health (eg ‘need for control and self-reliance’ and ‘privacy’) than physical health are in accord with the growing literature on ‘typically rural’ personalities and dispositions21,31-35. Men additionally endorsed ‘minimising the problem, resignation and normalisation’ and ‘emotional control’ more strongly in the mental health scenario, which supports the notion that rural men face more barriers to accessing mental health care than rural women. This is unsurprising given previous findings on men’s barriers to help-seeking in the context of mental health23,24, and their significantly higher rate of suicide36. Importantly, it also provides some insight into the attitudes specifically held by rural men that need to be addressed to improve mental health outcomes in this at-risk population.

The authors’ finding that both women and men perceive privacy (and stigma) as a barrier to accessing support for mental health issues is consistent with previous research that has highlighted the negative effect of stigma and rural people’s concerns about privacy when considering using mental health services13,14,17-19. However, while previous research has identified stigma as a particularly prevalent barrier among rural men24, this study provides evidence that concerns about stigma and privacy are also barriers faced by rural women. In addition, this study confirms the long-held but previously untested assumption that stigma/privacy is a lower barrier to help seeking for physical health conditions than for mental health conditions. However, given that these conclusions have been based on one item (‘Privacy is important to me, and I don’t want other people to know about my problems’), future research that uses a validated, comprehensive stigma scale is warranted.

The finding that no barriers were endorsed significantly more strongly by men or women in the physical health compared to the mental health context was expected, but is a new addition to the literature. The finding from the item-level analysis that men strongly endorsed barriers to seeking help for physical health issues, while women did not, is evidence of the need for strategies to increase help-seeking in rural areas for physical health issues too, which may be of particular benefit to rural men.

Further exploration of the data at the item level demonstrated that, other than the perception among women of long waiting times to access mental health services, strong structural barriers to seeking support for either physical or mental health conditions were not evident. This is at odds with the literature that suggests that direct and indirect costs of service utilisation18, limited availability of appropriate services17,35,37 and restricted public transport options38 act as major barriers to health service use in rural contexts39,40. However, the findings are consistent with Corboy et al’s conclusion that health professionals tend to report structural or system-based barriers to help-seeking in rural areas, while rural patients are more concerned with social factors and/or attitudinal barriers41. Similar differences in perceptions about barriers between providers and patients have been noted among rural Australian men with cancer accessing support41 and among Canadian, American and Dutch populations accessing mental health services42. This finding may also be explained by the fact that the regions from which the sample was drawn (the Riverland, Copper Coast/Yorke Peninsula and Eyre Peninsula) range from being ‘accessible’ to ‘very remote’ according to the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia, which categorises locations based on distance from service centres43. It is possible that structural barriers would have been more strongly endorsed if a higher proportion of the sample was drawn from more remote locations.

There are limitations of this study that should be acknowledged. The sample was limited to people living in three rural regions of South Australia who use a landline telephone that is listed in the White Pages non-commercial directory. Younger people and people for whom English is a second language were under-represented in the sample. Data was not collected on Aboriginal status or previous or actual health service use. The authors acknowledge that Aboriginal people are likely to be underrepresented in the sample (as they are in many studies of this type), which is problematic; that previous health service use is likely to impact upon future use; and that help-seeking intention is not a perfect predictor of help-seeking behaviour44. Longitudinal studies would be a useful addition to this field. Further, due to the lack of context-specific scales, the measure of help-seeking used had been developed among college men in the USA25. However, pilot testing showed it was acceptable in the present study’s target population and Cronbach coefficients for domains in the current study were slightly higher in women (range: 0.79–0.87) than men (0.68–0.86), supporting the appropriateness of the domain structure for both men and women in this context. Unfortunately, no test–retest reliability data relevant to the study sample are available.

As Judd et al. noted, to improve mental health help-seeking for rural people, we need to better understand attitudinal barriers and how to reduce them45. Further, resulting interventions should be founded on the well-developed behaviour change literature. By drawing on frameworks such as Michie et al’s behaviour change wheel46-48, and the notion that motivation, capability and opportunity must be present for a particular behaviour to be performed, dominant barriers should be matched with relevant evidence-based interventions. For example, the barrier ‘I wouldn’t want to overreact to a problem that wasn’t serious’ relates to both reflective motivation and psychological capability. Therefore, according to the behaviour change wheel (and the comprehensive literature underpinning this), the appropriate behaviour change strategies to address this issue include coercion, training, modelling and environmental restructuring48. As concerns about privacy (highlighted in the present research as an important barrier to seeking mental health services) relate to reflective motivation, psychological capability and social opportunity, the aforementioned strategies, plus education and persuasion, are likely to be most effective in addressing this barrier.

Finally, while the present study has made an important contribution by identifying many rural barriers to help-seeking for mental health issues, which may contribute to the high rate of rural suicide, the fact that very few barriers to help-seeking for physical health conditions were strongly endorsed (none by women) suggests that other potential contributors to the rural–urban physical health gradient (eg smoking and sedentary behaviour) need to be further explored.

Conclusions

The current discourse on health service utilisation in rural Australia is dominated by urgent structural issues such as recruitment and retention of health professionals across the full range of specialisations. The present study has demonstrated that attitudinal barriers, which are particularly restrictive in relation to mental health, also require careful consideration. Slade et al. found that only one-third of people with a mental health disorder in Australia had used relevant health services in the 12 months prior to being interviewed49. This is likely to be even higher in rural communities, and these findings together with the disproportionately high rate of suicide in rural Australia highlight an urgent national health priority. To minimise the burden of mental health issues on rural communities, evidence-based strategies must urgently guide responses by the mental health workforce and policymakers to change attitudes and increase the likelihood of rural people with ‘meetable’ mental health needs accessing appropriate and effective care in a timely fashion.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by a South Australian Cardiovascular Research Development Fellowship (#0000035126) awarded to Associate Professor Dollman. Additional funding was provided by a University of South Australia Department of Rural Health Support Grant.