Introduction

The Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population has a higher age-standardised cancer mortality rate than the non-Aboriginal population (221 per 100,000 vs. 172 per 100,000, respectively)1 and a significantly lower 5-year survival rate for all cancers than the non-Aboriginal population (40% vs. 52%, respectively)2, despite having a lower age-standardised incidence rate of cancer1. The discrepancy can be partly explained by the fact that the most common cancers in the Aboriginal population have high case fatalities3. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (respectfully referred to as Aboriginal people herein) from regional and remote areas experience even lower survival rates and poorer outcomes due to reduced access to health services, later diagnosis and more advanced cancer upon diagnosis4, less complete cancer treatment, and high rates of other co-morbidities3. The more remote the population, the greater the disparity5.

Aboriginal people from regional and remote South Australia and the Northern Territory who are diagnosed with cancer are often required to travel to Adelaide to access specialist cancer care services. However, the burden and expenses associated with transport and accommodation arrangements have been identified as barriers to accessing medical treatment for regional and remote Aboriginal cancer patients, who may additionally encounter cultural and linguistic barriers when accessing health services6. These inequalities underpin the need for culturally appropriate, educational cancer resources that facilitate the engagement of Aboriginal people7 to be implemented in conjunction with primary prevention strategies3.

To support Aboriginal Health Workers (AHWs) and services that work with Aboriginal families affected by cancer, Cancer Council South Australia led the development of The Cancer Healing Messages flipchart and patient flyer. The aim was to create culturally appropriate cancer support and information resources for use by AHWs, to guide their interactions with Aboriginal cancer patients and assist in the provision of effective and relevant support. AHWs are frequently key providers of information to Aboriginal people in their navigation of the health system after a cancer diagnosis.

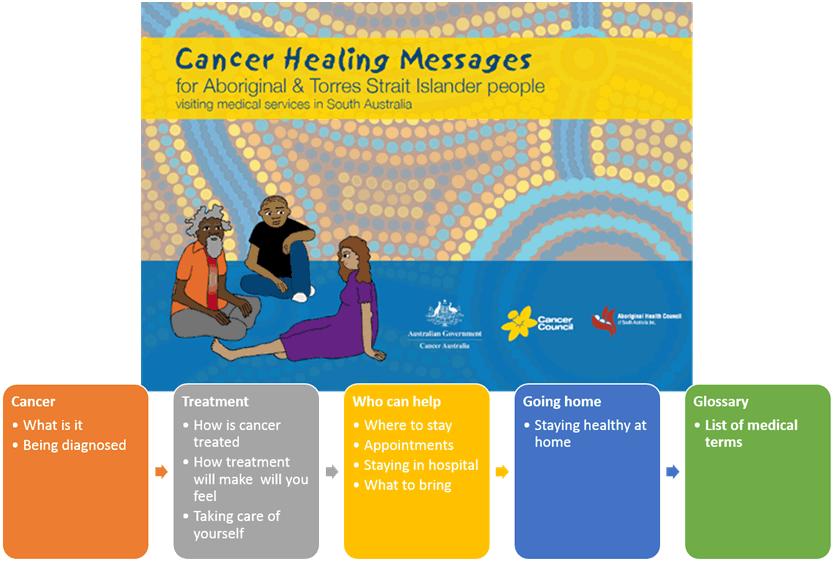

The 31-page Cancer Healing Messages booklet explains cancer and possible cancer pathways from diagnosis. The information is presented in a flipchart format, with alternate pages designed for use by AHWs and patients respectively. Flipcharts have been extensively used as tools to enhance health education among various groups8, including Aboriginal populations9,10. They are viewed by health professionals as practical, economical and easy-to-use educational tools that aid communication with patients and families10. The Cancer Healing Messages flipchart includes a glossary of commonly used medical terms, uses culturally appropriate language throughout and includes information on key topics (Figure 1). On the basis of research conducted with Aboriginal populations, which demonstrates that information presented visually is more effective than text alone11,12, visual imagery was included throughout the flipchart. Following recommendations from stakeholders, an accompanying patient flyer was also developed, which incorporates the most pertinent information in a take-home resource.

The flipchart and flyer were designed according to principles of best practice for developing acceptable and useful resources for Aboriginal communities13-15 and were deemed culturally appropriate for the Aboriginal population in South Australia by the project Advisory Committee, supporting partners and stakeholders. Both resources are available in printed, online and audio format (http://cancersa.org.au/get-informed/atsi/health-professionals) in English and Pitjantjatjara (Pitjantjatjara is the language and name of the Aboriginal people of the central Australian desert, including far north-west South Australia, extending into the Northern Territory and Western Australia). Pitjantjatjara was chosen as an appropriate Aboriginal language to use following consultations with Aboriginal Hospital Liaison Units.

The resources were distributed in 2010 in conjunction with a series of educational workshops, which delivered training to 166 AHWs on the information presented in the resources and the usage of the flipchart (including the AHW pages and patient pages). Following completion of the workshops, the resources were distributed to relevant services and agencies including Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services and health services in rural and remote areas of South Australia. The aims of this evaluation were to:

- Determine the current level of use (or intended use) of the resources.

- Identify barriers inhibiting use of the resources.

- Obtain feedback on the resources from target users.

Figure 1: Cancer Healing Messages flipchart key topics.

Figure 1: Cancer Healing Messages flipchart key topics.

Methods

Participants

In total, 64 individuals from 42 organisations that deliver health services to Aboriginal people across South Australia were identified as previous recipients or potential intended users of the flipchart and flyer. Although the target users were AHWs working with Aboriginal clients in rural and remote regions, due to the transient nature of the AHW workforce and the movement of the Aboriginal community between remote, rural and metropolitan areas, the resources were distributed more broadly across the state. Twenty-four organisations were based in metropolitan Adelaide, ten were regional, and eight were situated in remote regions of South Australia.

Procedure

An introductory email was sent to inform recipients about the evaluation of the Cancer Healing Messages flipchart and flyer, and the resources were then distributed via post. One week later, participants were emailed a survey link with details about how to request a hard copy of the survey or a telephone interview if preferred. Participants were reminded to complete the evaluation survey via email and/or telephone call 1 week later.

Survey

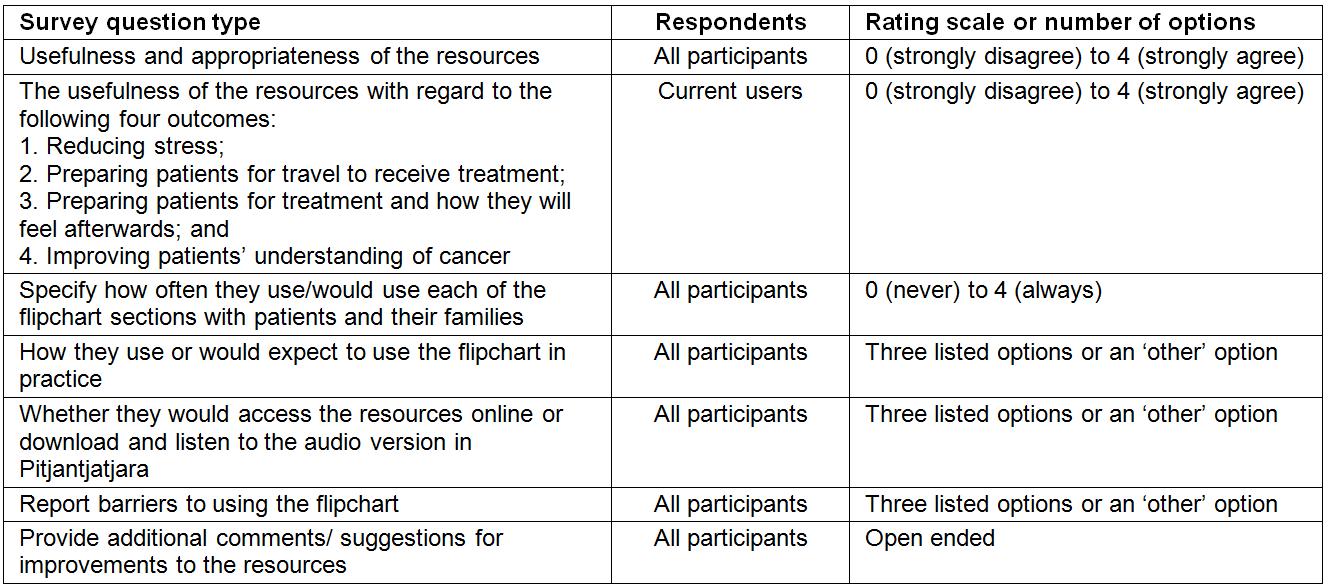

The survey asked participants to indicate whether they had previously received and used the resources, previously received but never used the resources, or received the resources for the first time. These groups are referred to as current users, non-users, and potential users, respectively (Table 1).

Survey questions were appropriately framed according to the participant’s experience with the resources. Information about participant demographics, job position, time in current role, and frequency of contact with Aboriginal cancer patients was also collected. The survey was designed to be brief, to encourage participation and minimise respondent burden.

Table 1: Questions from the Cancer Healing Messages flipchart and patient flyer evaluation survey

Data analysis

Responses are presented as frequencies and sample sizes vary due to missing responses. Participants’ comments are summarised into key themes: Perceived usefulness of the resources; Use of the resources; Barriers to using the resources; and Additional feedback. Findings are summarised for the total sample and, where informative, the patterns of responses for current, non-users and potential users are presented.

Ethics approval

This study received ethics approval from the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (AHREC). All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the AHREC, the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2007), and the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research (2007).

Results

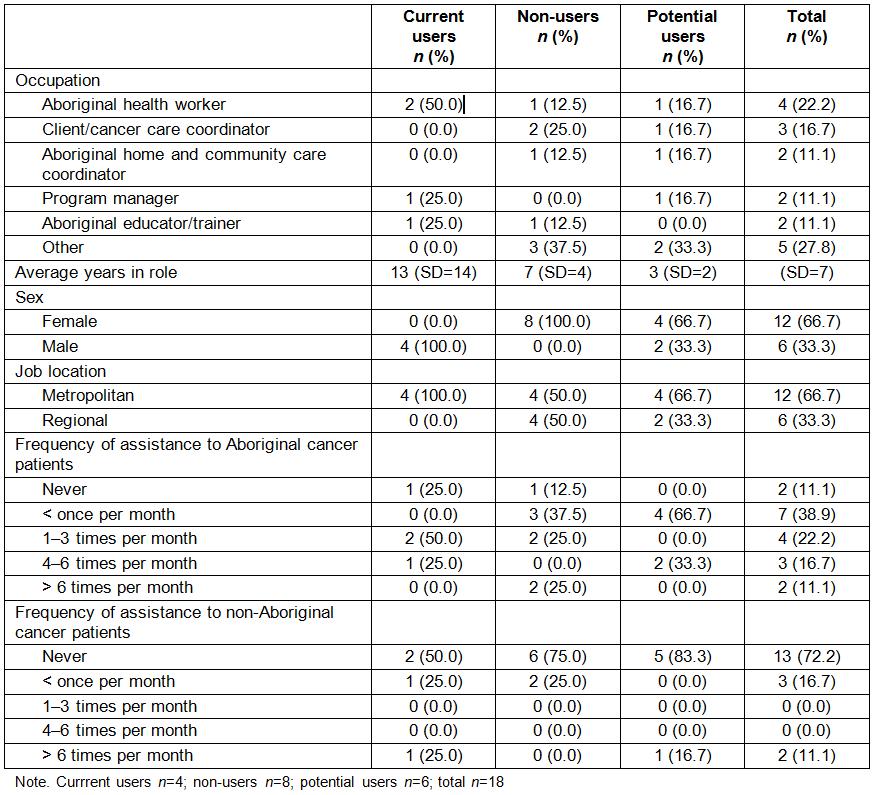

Eighteen participants completed the survey, including 4 current users, 8 non-users and 6 potential users (Table 2). The majority were female (67%) and worked in metropolitan areas (67%).

Table 2: Participant characteristics from the Cancer Healing Messages flipchart and patient flyer evaluation survey

Perceived usefulness of the resources

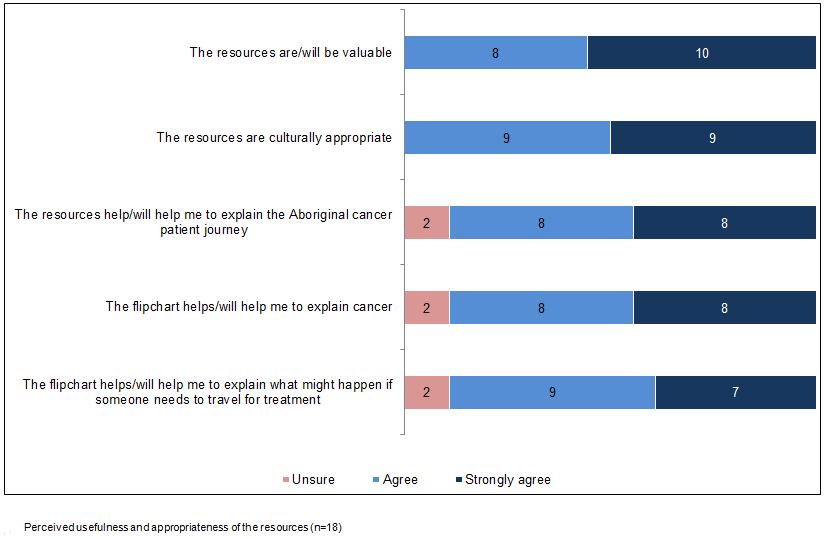

The majority (89–100%) of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the flipchart and flyer were valuable, culturally appropriate, useful for explaining the Aboriginal cancer patient journey, useful for explaining cancer, and useful for explaining what might happen should a client need to travel to receive treatment (Figure 2). All participants agreed or strongly agreed that the resources were useful for giving Aboriginal cancer patients and their families a better understanding of cancer, preparing them for travel to receive treatment, and preparing them for treatment and how they will feel afterwards. All but one participant agreed or strongly agreed that the resources would be useful for reducing stress.

Figure 2: Perceived usefulness and appropriateness of the resources (n=18).

Figure 2: Perceived usefulness and appropriateness of the resources (n=18).

Use of the resources

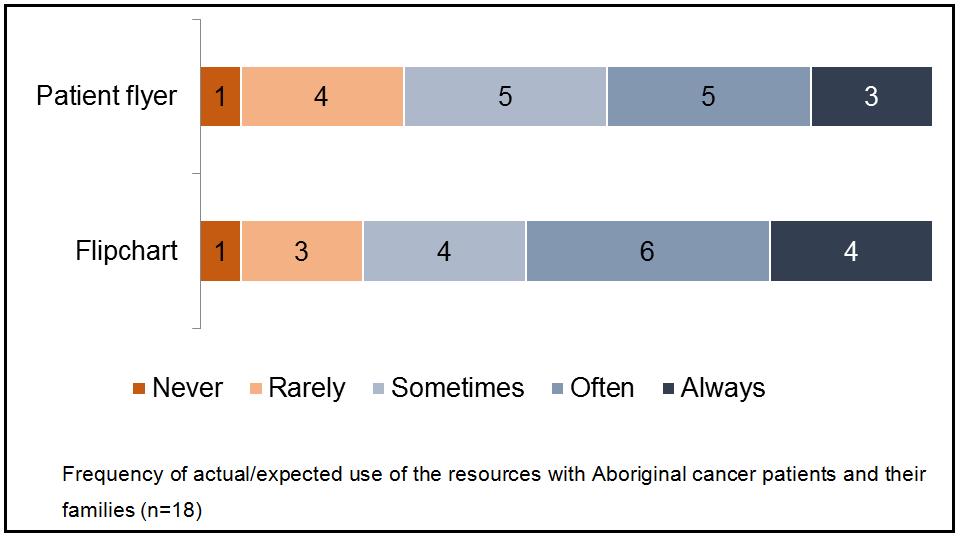

Frequency of flipchart and flyer use: All sections of the flipchart were used or expected to be used with a similar frequency, therefore responses for all sections were combined (Figure 3). The majority (78%) of participants said they would use each flipchart section ‘sometimes’ or more frequently. When asked to indicate how often they used/would use the patient flyer with patients and their families, three-quarters (72%) of participants reported that they would use it ‘sometimes’ or more often. One participant stated that they had never used the flipchart or flyer because they worked with cancer patients who were already receiving treatment.

Figure 3: Frequency of actual/expected use of the resources with Aboriginal cancer patients and their families (n=18).

Figure 3: Frequency of actual/expected use of the resources with Aboriginal cancer patients and their families (n=18).

Flipchart use: Thirteen participants (76%) reported that they used/would use the flipchart differently for each patient, two participants (12%) reported that they would use selected pages, and two participants (12%) reported that they used the whole resource in sequence.

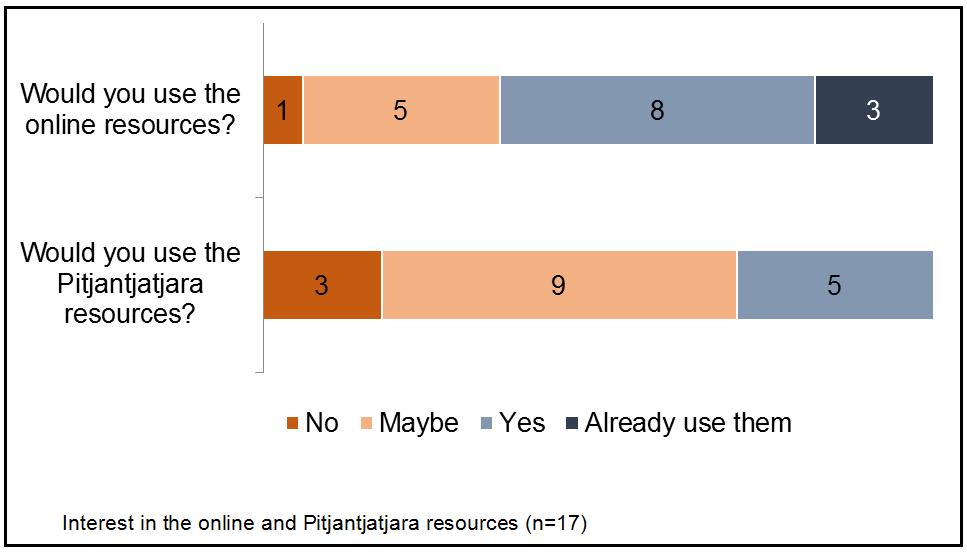

Online resource use: The majority of participants (76%) reported that they were, or might be interested in using the online resources, while 18% indicated that they had already used them (Figure 4). The majority of participants (82%) also reported that they were, or might be interested in using the Pitjantjatjara resources, although none had used them previously.

Figure 4: Interest in the online and Pitjantjatjara resources (n=17).

Figure 4: Interest in the online and Pitjantjatjara resources (n=17).

Barriers to using the resources

The most commonly reported barrier to using the resources was that they are not appropriate for some patients (n=9), followed by not having enough copies of the flipchart available in consulting rooms (n=5) and the resources not being available when making home visits (n=3). Additionally, participants reported that even when the resources were available, they were not being used by staff, the presentation may be too simplified for some clients, and that health care workers are unlikely to use the resources in hospital settings as patients may have already commenced treatment.

Additional feedback

Three participants (one non-user and two potential users) made suggestions for improvements to the flipchart. One suggestion was to include a skeleton diagram as a visual aid, and another was to flip the orientation of the top pages of the flipchart so that they face the same way as the bottom pages. One current user commented that the flipchart is a valuable resource and can also be used as a training tool. Among non- and potential users, comments indicated that the resources were perceived as informative, easy to understand, and useful for community workers who directly support patients. One participant suggested the resources be made available to the whole community, not just regional and remote populations.

Discussion

The present study reports on the usage and uptake of the Cancer Healing Messages resources, which were developed in response to the lack of culturally specific resources available for health workers assisting Aboriginal cancer patients and their families. The results confirm the acceptability of the resources among target users who were not involved in the development process, as all participants agreed that the resources were culturally appropriate and would assist them in explaining cancer and the cancer journey. Furthermore, all current users agreed that the resources improve patients’ understanding of cancer and preparedness for treatment and related travel.

Flipcharts are a preferred health education tool in populations with lower overall and health literacy, but in order for flipcharts to be used effectively, it is essential that flipchart users receive adequate training8. The provision of training is important because it builds users’ confidence, knowledge and skills to utilise the resource effectively and as intended9,16. When the resources were initially developed, educational workshops were conducted with 166 potential users of the flipchart. However, due to the high turnover of staff in the Aboriginal health workforce, it was not possible to recruit any of the initial workshop attendees to participate in the evaluation. A high rate of staff turnover has been previously identified as a barrier to successful implementation of health promotion programs, particularly within remote communities in Australia9.

The results suggest that the evaluation participants (none of whom had participated in the training workshops) were not all familiar with how to use the resources. This lack of training meant participants reported using the flipchart in different ways than were intended. For example, one participant suggested that the orientation of the chart be flipped so that the top pages of the flipchart face the same way as the bottom pages, reflecting a misunderstanding about how to use the patient and health worker pages separately. Due to the transient nature of the AHW population, it would be beneficial if electronic educational materials explaining how to use the flipchart were available. The provision of a guide on how to use the Cancer Healing Messages flipchart would be a cost-effective way to educate AHWs, inform new employees about the correct use of the flipchart and ensure ongoing employees stay up to date. Although the guide would ideally be used as a supplement to face-to-face training, it would enable further reach of the resources to those unable to participate in workshop training. Ideally, the resources should be promoted in the context of existing training and development for AHWs, and considered as a standard practice tool for AHWs working with cancer patients.

The results indicate that, despite being viewed as appropriate and valuable for use with Aboriginal cancer patients and their families, utilisation of the flipchart was low. This discrepancy highlights the need for a clear dissemination strategy and long-term implementation plan that involves relevant education and training to achieve broad reach and utilisation of the resources. Strengthening organisational partnerships may also encourage incorporation of the flipchart into routine practice17. Other studies examining the uptake of educational materials in the Aboriginal population have found that a clear dissemination strategy, incorporating relevant training and support materials, can help build capacity18 and lead to successful uptake9,10,16,19.

The number of non-users indicates that there may be barriers to using the flipchart in practice. Lack of appropriateness for some patients was the most frequently reported barrier to using the resources. One participant suggested that health workers often see patients at a later stage of the cancer journey after treatment has commenced, and therefore using the flipchart would be inappropriate. Another participant commented that the content was too simplified for their clients, which illustrates the challenge of developing a suitable resource that can cater to the variability in the population. Other barriers that contributed to low utilisation included not having enough copies of the flipchart or not having it available at home visits. To address these issues, organisations could be provided with additional copies for clinic appointments and (if appropriate) tablet-compatible versions could be developed for use during home visits.

Current evidence suggests targeted and tracked promotion of resources can assist in generating interest in the target audience and lead to effective dissemination18. In the short term, promotion of the resources is required to encourage familiarity with the flipchart and confidence to use it in routine practice. This is particularly important for AHWs who have infrequent contact with people affected by cancer and may find it more difficult to incorporate use of the flipchart into their practice. In our sample, half of the participants reported seeing Aboriginal people affected by cancer less than once a month. It is therefore important to remind AHWs, particularly those who have only intermittent contact with cancer patients, that the resources are available via ongoing promotion.

Accredited cancer education has been developed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals (HLTAHW035 – Provide Information and Support Around Cancer) and in South Australia the flipchart is included in the training materials. The HLTAHW035 course was developed for delivery over 4–5 days and provides cancer information and awareness education but does not include specific training about the utilisation of the flipchart. There is no publicly available information regarding evaluation of this training.

The implications for rural delivery include exploring the current needs of rural and remote AHWs in relation to how to best support their clients affected by cancer, determining whether flipchart training in rural and remote areas would be of value and gathering input into how the flipchart could be updated and improved.

The findings from this evaluation should be considered in light of several limitations. First, despite attempts to recruit as widely as possible, AHWs were a difficult population to access, and only a small sample size was obtained, preventing broader generalisation of the results. Second, there was a low proportion of participants from regional or remote areas, who are the intended target users of the Cancer Healing Messages resources. This resulted in metropolitan-centric data, which limited the ability to draw conclusions about the utilisation of the flipchart in rural and remote areas. Third, it was not possible to recruit into the study any AHWs who had participated in the workshop training on how to use the flipchart. This prevented comparisons of the use of the resource by participants who had and hadn’t been trained to use the resource, and the capacity to draw conclusions about the impact of the training on the use of the flipchart.

Conclusion

This formative evaluation has identified some of the barriers inhibiting use of the Cancer Healing Messages resources and proposed recommendations for increasing their uptake and sustainability, including a revision of the implementation approach. Ongoing evaluation is required to ascertain whether AHWs are accessing and utilising the flipchart, and to determine their confidence in using it. Ongoing evaluation should also consider improvements to the flipchart based on regular feedback from users. The evaluation findings have demonstrated that broad and effective dissemination of health promotion materials in the Aboriginal community requires not only engagement and collaboration to ensure acceptability, but long-term implementation strategies to ensure utilisation is high and sustainable. Furthermore, the success of the implementation process requires regular review to determine whether the resources are improving equity of access to support services for Aboriginal cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all of the South Australian Aboriginal Health Workers, Aboriginal Health Services and Aboriginal community members who contributed to the resources and this evaluation. We would also like to thank the Aboriginal Health Council SA, the Aboriginal Liaison Unit of the Royal Adelaide Hospital and the Aboriginal Health Division SA Health for their support of this project. Editing, illustrations and design for the resources were completed by Dreamtime Public Relations. The Cancer Healing Messages resources were developed with a Cancer Australia Collaborative Cancer Support Networks (CanSUPPORT) grant awarded in 2008 with matched funding from Cancer Council SA.