Introduction

The complexity of contemporary health care demands interprofessional collaboration (IPC) and teamwork1,2. WHO defines IPC as ‘when multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, carers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care2(p.7) and has advocated for IPC for several decades. In its most recent Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice2 the WHO reasserts that effective interprofessional education (IPE) is necessary for preparing a collaborative practice-ready health workforce. There is mounting support, nationally and internationally, for IPE to be embedded in undergraduate learning to ensure students are equipped with the requisite knowledge, skills and attitudes for employment in the healthcare sector3-5. Given the need for graduates to be practice-ready, pre-qualification IPE can be seen as ‘an investment in the future…’ 4(p.16). Interprofessional education is defined as ‘when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’6. For the purpose of this review, IPE is interpreted as applied by Reeves and colleagues 4(p.5), as ‘… all types of educational, training, learning or teaching initiatives, involving more than one profession in joint, interactive learning.’

The increased momentum of IPE in Australia mirrors international activity3,7-9, although it is yet to become embedded across all health professional curricula and the clinical learning environment3,7,8,10. In Australia, despite efforts to progress a national agenda, IPE remains a disparate range of fundamental or grass roots activities, often in rural environments, with no shared vision and little synchronisation within and between states and territories3,7,11,12. The clinical learning environment constitutes an integral part of undergraduate healthcare curricula where the links between theory and practice are optimised through work-integrated learning13-15. Accordingly, the clinical learning environment affords an ideal setting for promoting IPE, understanding IPC and developing the skills required to facilitate transition from student to collaborative practitioner4,16-18.

Since 1999, there have been a number of Cochrane reviews, Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) reviews and other scoping and integrative reviews that reflect a growing body and higher level of evidence supporting IPE. In their literature review of 83 IPE studies, Abu-Rish and colleagues16 cited more than 20 related reviews. In cataloguing these reviews, they noted that IPE research has predominantly targeted three key themes: the conceptual basis for IPE and associated competencies, research methods signifying effective teamwork and communication, and developing sustainable models for applying IPE to health professional curricula and clinical practice16. Although Reeves, Zwarenstein and colleagues, key authors in the IPE field, have undertaken multiple reviews related to IPE interventions and outcomes 4,19-24, none of these reviews consider the implications of IPE in the context of rural practice settings or clinical learning environments.

Despite the growing body of IPE literature, little is known about rural clinical learning environments and their capacity to support IPE. To the knowledge of the authors, only one review has explored IPE in rural clinical settings and its focus was on paramedic involvement25. This represents a noticeable gap in knowledge because there are increasing expectations that students will be exposed to rural practice settings, IPE will be provided to students undertaking workplace learning2,5,15 and graduates will be ready for IPC2. Other factors fuelling the need for a review that maps IPE in rural settings include:

- the movement towards community-based person-centred care26-28

- the reliance in rural health on IPC29-31

- efforts to build placement capacity in non-acute, including rural, settings15,32

- the drive to increase students’ engagement in rural practice to address workforce shortages26,33.

Furthermore, if the clinical learning environment is considered an ideal location for promoting work-integrated learning and preparing practice-ready graduates, attention is warranted to exploring the potential for IPE in rural as well as other contexts. This review seeks to address the gap in knowledge about IPE in the rural context. Accordingly, the focus has been to map the rural IPE landscape; that is, the learning opportunities available in rural settings, the settings involved, the nature of IPE provided to students undertaking rural placements, the types of students (disciplines) that have access to IPE in rural settings and the outcomes of IPE in the rural context.

In rural areas, the community represents the platform for care34,35. Killam and Carter note that ‘distinct characteristics of rural areas include isolation, limited access to healthcare resources, small populations, significant distances between services and providers, and informal social structures’(p. 2)31. There is a well-established body of evidence that associates rural practice with care across the lifespan, advanced generalist knowledge and integrated collaborative care29,30,35. This integration of health and social care, and continuum of community and hospital care, makes it especially important that rural health professionals are equipped for IPC 31,35,36. For undergraduates to be equipped with the prerequisite skills and attitudes for IPC, they need to experience these in the practice setting35,37-39.

Evidence suggests that ‘rural placements have the potential to provide a better learning experience than that of the urban campus, due to the close contact between student and supervisor in the rural setting’40(p.122). Rural placements are often in smaller settings such as small rural hospitals and community-based health services where students learn and gain experience in a multidisciplinary team environment with health professionals often well known to each other35,36,41. Like other primary healthcare settings, one of the benefits afforded by rural placements is the opportunity to experience IPC within a close-knit community of practice30,35,41,42. Rural placements have been shown in before-and-after studies to improve interprofessional abilities and influence future collaboration in the workplace34,39,43. Rural practice settings may therefore be an ideal IPE environment for students because they provide a range of opportunities for students to follow the patient journey and work across the continuum of care and professional boundaries34,39,41,44.

There is potential for other practice settings to provide IPE, but the inherent importance in rural practice of sustaining collaborative interprofessional relationships renders the lack of attention to IPE in the rural context a critical omission in the literature. While there is considerable scholarship about rural clinical learning environments, the notion of IPE in these settings is relatively new and has not received the same level of attention that it has in more urban and classroom settings. Having more than a decade of experience in teaching and studying IPE, the authors were cognisant of the need for a review to address the gap in knowledge about IPE in the rural context. The aims of this review were to identify, analyse and synthesise the research available about the nature of and the potential for IPE provided to students undertaking rural placements, the settings and disciplines involved and the outcomes achieved.

Methods

The integrative review process outlined by Whittemore and Knafl was adopted for this review, ‘allowing for the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research in order to more fully understand a phenomenon of concern’ 45(p.547). An integrative review process was considered the most appropriate method because of the diverse and complex nature of IPE, the range of disparate research methods used to study IPE4,16 and the applicability of this process to build theoretical understanding and to guide policy and practice46,47. Moreover, as a ‘new emerging topic’, the notion of IPE in the rural practice environment was well suited to an integrative approach47(p.356).The five-stage process outlined by Whittemore and Knafl incorporates problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation of integrated findings45. The process was expanded in recognition that integrative reviews can also synthesise data, include theoretical and empirical data and fulfil a range of purposes, such as the development of a conceptual framework or identification of a research agenda46,47.

Problem identification

The increasing complexity of contemporary health care is driving the need for effective teamwork and IPC, which in turn, is increasing the impetus to facilitate IPE within the clinical learning context1,2,5,7,24,48. The need for IPE is compounded by current and projected workforce shortages in rural health worldwide5,40,49,50, increasing expectations that students will undertake rural placements40,48, that IPE will be provided to students undertaking workplace learning7, and the need to graduate collaborative practice-ready health professionals2.Collectively, the drivers stimulating IPE in rural practice settings necessitate a review of the nature of and potential for IPE available for students undertaking rural placements.

Literature search

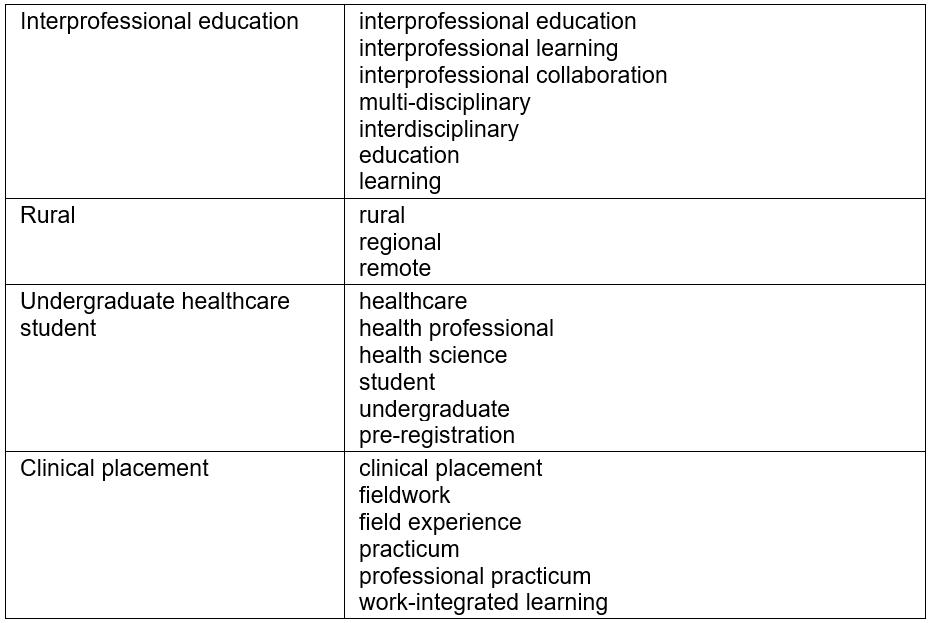

Nine databases were searched: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google Scholar. A range of search terms were used to ensure the different nomenclature and related concepts used by different disciplines were incorporated by the search strategy (Table 1).

The search strategy was adapted to suit each database and the Boolean technique using AND/OR was applied to capture similar or interchangeable concepts. To promote rigour, the reference lists of retrieved articles were searched manually by the first author to identify additional studies and published reports of IPE initiatives not captured by the search strategy.

The inclusion criteria included primary research and reports of IPE activities in rural settings, peer reviewed and published in English between 2000 and mid-2016. The timeframe was chosen purposefully by the authors to capture the increased focus on rural placements and expectations since the turn of the century that students will be exposed to IPE, developing trends in IPE and the outcomes of longitudinal studies5,24. For the purpose of this review, the clinical learning environment is recognised to include rural and regional hospitals, multi-purpose services, community health services, general medical practice settings, community pharmacies, mobile and outreach health services and rural communities. Exclusion criteria included postgraduate and professional development activities, lack of evaluative detail and uniprofessional studies involving students working with health professionals from other disciplines.

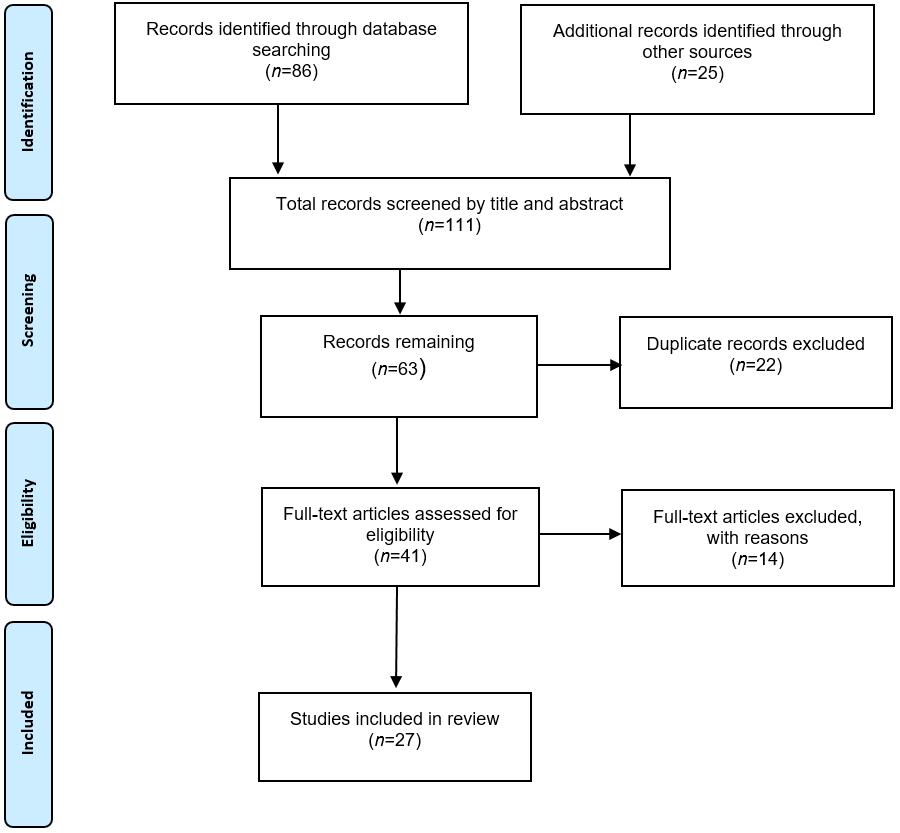

The search was undertaken by the first author with advice from a research librarian. Titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The initial search, including those sourced from reference lists, identified 111 articles. After reviewing the titles and abstracts against inclusion criteria, 63 were retrieved for detailed review. Duplicates were eliminated, leaving a total of 41 articles. Ten studies were reported twice and four lacked detail, effectively reducing the number of included studies to 27 (Fig1). Similar to the approach adopted by Reeves and colleagues23, studies were not excluded on the grounds of methodological quality but were examined with a specific lens prescribed by the review objectives and inclusion criteria47.

Table 1: Search terms used as part of the search strategy within the nine chosen databases

Figure 1: Flow diagram of article selection process.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of article selection process.

Data evaluation and analysis

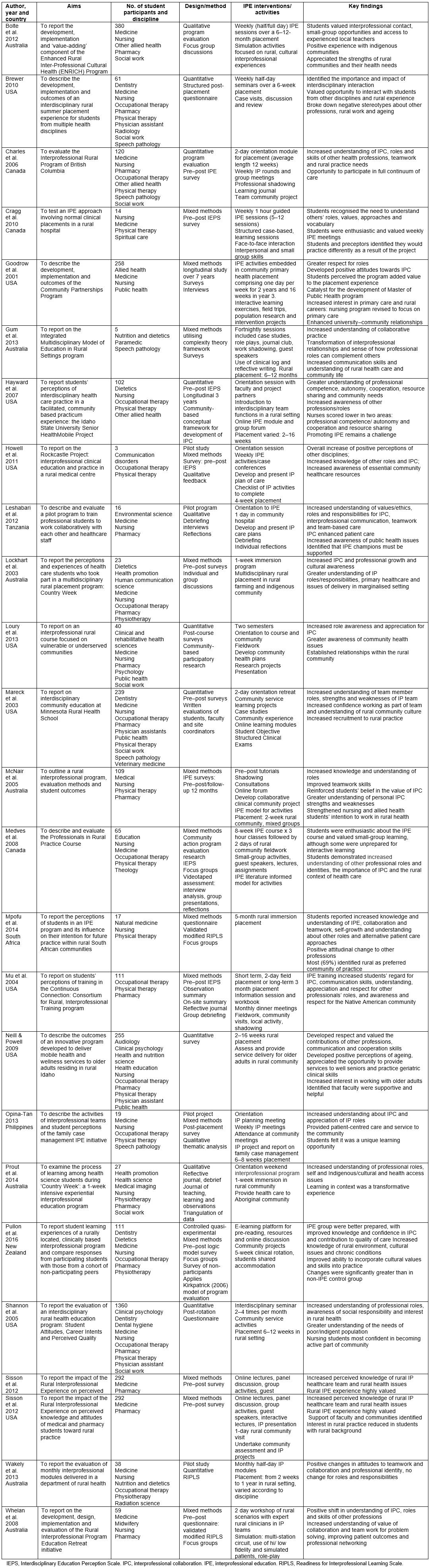

The authors devised a data extraction tool that addressed the review aims. The first author undertook the data extraction. To facilitate evaluation and analysis, the authors independently appraised and collectively reviewed the included studies. Findings were aggregated where meaningful, for example the disciplines engaged in IPE. Content was analysed manually to identify and extract the main ideas and themes as they related to the research aims; in other words, identifying and analysing the nature of the IPE initiatives available to students undertaking rural placements, the settings, students (disciplines) involved, methods used to evaluate outcomes, and the outcomes achieved (Table 2). Recurring patterns and themes were analysed together with similarities and differences, outliers and learning interventions. This process facilitated description, aggregation, abstraction and elicited insights into some of the reported challenges to provision of IPE programs. The IPE activities described in each report were compared and contrasted, observing for patterns, congruence across jurisdictions and unique identifiers. Meanings were discussed, abstracted and synthesised by the authorship team and any differences were resolved by consensus.

Table 2: Overview of included studies

Results

The 27 studies reviewed were undertaken in seven countries: Australia (10), USA (10), Canada (3), and one each from New Zealand, Tanzania, South Africa and the Philippines. Despite geographical, cultural and health system differences, the studies reviewed were all concerned with developing collaborative interprofessional practice-ready graduates. Data were collected in similar ways, utilising a range of procedures such as student surveys, focus group discussions and/or debriefing. Two studies also utilised direct observation: one through the use of facilitators51, the other by video capture52. A mixed methods approach was adopted in 15 of the studies, nine were quantitative, and three qualitative. Eleven applied a controlled pre–post study design. Only one longitudinal study was reported43. There were no randomised controlled trials related to IPE in the rural context although one quasi-experimental study with a comparator group of non-participating students was reported53. Some studies utilised validated survey tools: three used the Interdisciplinary Education Perception Scale (IEPS), one used the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS), two used a modified version of the RIPLS and one used the Team Performance Scale. Other studies utilised customised survey tools; however, the development, pilot testing and psychometric properties of these instruments were not reported.

Settings

The IPE activities were undertaken in a combination of university and rural placement settings including hospitals, community health centres and other community venues. The settings ranged from an immersion simulation exercise at rural sites in Australia54,55 to a mobile outreach program that promoted access to primary health care for an under-served migrant population in the USA56. The most common setting for IPE activities was community-based primary care where students identified healthcare needs and developed related activities. Several studies – one in Canada, one in Australia and two in the USA43,56-58 – emphasised that the community were joint participants in the IPE activities and provided support for the IPE undertaken. Loury and colleagues56 noted that the growth of a collaborative team requires community partners, students and faculty to share common goals. Brewer59 reported that although their program received funding support from the local area health education centre, financial constraints may impact on programs.

Participants

Overall, the 27 studies reviewed reported IPE activities involving a total of more than 3800 students. The number of participants in each ranged from three60 to 1360 61. All studies except for one62 included students from at least three professions. Although nursing and medical students predominated, collectively the IPE studies reviewed included students from 36 disciplinary fields. There were several ‘outlier’ groups, such as theology, veterinary medicine, natural medicine and human communication science. Student demographics were rarely identified and academic levels were reported inconsistently. Students’ participation in IPE was predominantly voluntary and not mandated as part of their undergraduate course.

Interprofessional learning activities

The nature of the rural clinical learning environment in a range of settings and countries provided rich and varied interprofessional learning opportunities for students to engage with other disciplines and participate in a broad range of IPE activities. Some IPE initiatives were a ‘one-off’ or pilot44,60,63-65, several programs had been offered successively for 3 years or more39,55,57 and two for 10 years66,67. Regardless of the country of origin, the most frequent IPE activities were seminars, tutorials, discussion groups (n=21, 84%), case presentations (n=11, 44%) and community projects (n=11, 44%).

The most utilised IPE format was an initial orientation or discussion followed by interacting with clinicians during placement. This practice-based role-modelling format was considered conducive to developing a greater understanding of teamwork, interprofessional communication and collaborative practice52,68. Community-based participatory research was a key element of one program which involved students writing scholarly papers, posters and attending conference presentations56. The timeframes dedicated to IPE activities varied considerably, for example a one-day rural community visit, a structured weekly program over two semesters and a whole-of-course program for 3 years (Table 2).

Outcomes

All 27 studies reported a range of positive learning outcomes. The most common outcomes assessed were students’ attitudes toward IPE, knowledge of and respect for roles of other professions and development of collaborative skills such as communication, shared decision-making and conflict resolution. All studies reported evidence of changes in the attitude or perception of students. Two studies reported the breaking down of ageing stereotypes and increased interest in working with older adults59,69. Three studies reported increased student understanding of the diverse needs of the rural community and intent to practice rurally39,61,66. In contrast, Sisson and Westra found that although the rural IPE experience was highly valued, interest in rural practice was reduced in students with a rural background62.

Only one study reported the longitudinal assessment of change in behaviour or attitudes43. Using the IEPS pre-test–post-test instrument, Hayward and colleagues43 reported a significant difference (p≤0.001) in changes in behaviour and attitudes for all students over a 3-year period. There were also statistically significant differences between discipline categories: nursing students scored lower than other disciplines regarding professional competence and autonomy and on cooperation and resource sharing within and across disciplines (p≤0.011).

Engagement in IPE enabled students to develop a greater understanding of their own and other professional roles, the value of other professions and the importance of teamwork (Table 2). Students found being involved in the full continuum of care that occurs in rural settings beneficial and gained greater understanding of the complexity of rural healthcare issues and practice63,70-73. Likewise, local clinicians and communities reported positive benefits from having students and developed a greater understanding of IPE, students’ needs and the complexities of placement43,67.

Discussion

This review summarises and synthesises the research available about the nature of and potential for IPE initiatives offered to undergraduate students undertaking rural placements, the students involved and the outcomes achieved in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of IPE in the rural context. The rural setting was chosen because of the drive to build placement capacity by increasing students’ exposure to expanded settings, including rural practice15,40, the collaborative nature of this environment and the reliance in rural practice of sustaining effective interprofessional relationships34-36,41. Inevitably, the context of learning environments influences the capacity of agencies to provide IPE and the type of IPE opportunities available. The variation between studies reveals the heterogeneity of rural clinical learning environments and eclecticism of IPE programs as reported in other IPE reviews4,16,22, but also similarities and relevance across different jurisdictions. The differences also reflect alternative ways that placements are configured, IPE is conceptualised and the types of students that are ‘connected’ to engage in IPE. The similarities in focus may partially reflect the international uptake of the WHO framework2.

A range of activities were undertaken, from seminar-based group discussions to observation-based learning where students were closely engaged with the community. However, although Barr and colleagues74 identify simulation as a modality for IPE, it featured in only four of the studies reviewed. As simulation is being increasingly adopted in academia and clinical practice settings75, its use and potential in rural IPE warrant further investigation.

Recently, there has been a focal shift in the mainstream literature to underpin IPE with theoretical foundations23,76. According to Barr and Low ‘all IPE is more coherently planned, consistently delivered, rigorously evaluated and effectively reported when it is built on explicit and clear theoretical foundations’ 76(p.18). Only two of the studies reviewed provided a clear outline of the theoretical framework employed44,52.

Scheduling and sequencing IPE activities were considered challenging but critical for meaningful collaboration to occur. The challenges of scheduling IPE activities are not unique to rural practice and have been identified as problematic in other settings7,77-79. In the studies reviewed, IPE activities were invariably developed by academics and not always in collaboration with clinical leaders and clinicians. Where clinicians were involved in the development of IPE, there was a greater focus and acceptance of these activities, which in some instances led to ongoing programs66,67. Four studies identified implementation and sustainability issues related to lack of funding and staffing52,53,66,79.

Few studies reported the validity or reliability of evaluation instruments. Researchers that reported the validity of instruments principally used those with established psychometric rigour, such as IEPS and RIPLS. However, there is some debate over the utility and psychometric integrity of these instruments for measuring outcomes of IPE80. This debate highlights the need to review existing instruments for their validity and relevance to the rural context. Additionally, the lack of description of the evaluation instruments used undermines replication. The findings reported most frequently were individual student outcomes: increased IP understanding, respect for professional roles and IPC, and a sense of how individual professional roles can complement others. These learner-focused outcomes reflect those reported in other reviews81,82. While most studies identified improved communication skills and transformed relationships between student groups, other outcomes included increased understanding of rural health issues and healthcare needs83-85.

There is some evidence that IPE provided in context in a clinical learning environment has more impact on learning outcomes than classroom-based IPE11,85. The benefit of IPE situated within the clinical learning environment is consistent with the need for students to have work-integrated learning experiences that immerse them in the actualities of everyday practice85,86. In the workplace setting, students can engage professionally with clinicians, including those from other disciplines, begin to unravel the elements of being interprofessional and develop an understanding of IPC in context11,35,44,85.

Although the level of IPE evidence available in the rural context precludes the development of a robust conceptual framework, there are signposts in the literature to guide those interested in providing IPE in rural settings. These include the need to assess the local rural IPE landscape – that is, the opportunities and resources potentially available, such as:

- identifying local interprofessional learning opportunities

- incorporating primary care into student placements

- identifying IPE leaders/champions to facilitate the planning, organisation and development of activities and programs

- exploring simulation resources suitable for IPE

- accessing discipline experts (eg visiting specialists)

- involving local communities

- providing opportunities for students to share meaningful IPE experiences with other disciplines.

This review contributes a more comprehensive understanding of the nature of and potential for IPE available to students in rural clinical learning environments; however, there are a number of limitations.

Limitations

Although all 27 of the studies reviewed reinforced the value of providing IPE in the rural setting, this review is limited by the lack of IPE research in this context, the heterogeneity of studies, limited use of validated tools and the dearth of longitudinal evidence. Such variation mitigates meta-analysis, limits understanding of the benefits of IPE in rural settings over time and, specifically, its relationship to IPC. The integrative review process allows for synthesis of all of the data from primary sources regardless of level of evidence; however, lower levels of evidence preclude the findings being generalised. While only one study was quasi-experimental and reported control groups53, Stone argues that this type of research may not be optimal for evaluating IPE87. According to Stone, the use of randomised controlled designs in this sphere ‘where there are too many variables that cannot, and in most cases probably should not be controlled for’87(p.263} would limit the studies undertaken and the knowledge gained.

Although the literature search was extensive, some studies may have been missed by the search strategy because of the content of titles and abstracts, those published in languages other than English. Others may have been missed due to lack of information, or because of researcher bias. The reviewers are invested in the field and therefore may have unwittingly ascribed bias to the review process. To mitigate bias and promote rigour, advice was sought from a research librarian, and the authors individually searched for additional articles, independently reviewed the articles and collectively discussed the findings. Another limitation was that this review focused on IPE opportunities for students from different disciplines undertaking rural placements to interact, engage and learn with and from other students. As such, it does not address the opportunities the rural clinical learning environment affords for students to work individually within a small interdisciplinary team or the potential of other learning environments to provide IPE. Finally, although the scope of the review focused on profiling the IPE initiatives provided to students rather than exploring the challenges and barriers, some findings suggest these warrant further investigation.

Conclusion

This review reinforces the immaturity of the concept of IPE in the rural context. It addresses an important gap in the existing IPE literature and provides Australian and international evidence that a range of IPE initiatives are available to diverse student groups undertaking placements in rural practice settings. The findings demonstrate the potential that rural settings can offer for promoting IPE to students; the outcomes achievable such as interprofessional understanding, professional respect for other roles, collaboration and teamwork; and greater understanding of the collaborative and interprofessional nature of rural practice. Rural clinical learning environments afford a rich resource whereby students and practitioners can create constructive and transformative IPE experiences. This review contributes new insights to inform the practice of IPE in rural areas and provides a compelling case supporting the development, trialling, evaluation and translation of IPE in the rural context. Furthermore, this review proposes a research agenda to help build and develop a conceptual framework that could support rural IPE. The agenda includes higher level research that examines the prerequisites for optimising IPE opportunities, the challenges to developing sustainable IPE programs, the potential for simulation-based IPE in rural settings and the impact of IPE on IPC and health outcomes over time.