Introduction

The relationship between tobacco use and consequent disease burden is an issue of social justice 1. People who are poor, less educated and marginalized have higher rates of smoking compared to their more privileged counterparts. They also suffer tobacco-attributable morbidity and mortality at significantly higher rates. These circumstances operate in the Appalachian region of the state of Ohio, USA, a rural area differing from the state on important social and economic characteristics relevant to tobacco control. Socioeconomic disadvantage2, smoking prevalence3, and incidence of cancer and heart and lung disease4 are all heightened in Appalachia in comparison to other regions of Ohio.

Notably, women residing in rural Appalachia have high proportions of poverty, low educational attainment and employment in unskilled positions, compared to other groups2,5. The smoking prevalence among adult women residing in Appalachia is higher than in the remainder of Ohio (26.6% vs 20.3%)3. Risk factors for smoking among female residents of Appalachian Ohio include younger age, low socioeconomic position, depressive symptoms, and first pregnancy before age 206. The proportion of Appalachian women who smoke during pregnancy is estimated to be as high as 35–40%7. Fewer households in Ohio Appalachia ban indoor smoking, as compared to Ohio non-Appalachian counties8.

Social and contextual factors including, but not limited to, socioeconomic status, social networks, worksite conditions and neighborhood resources have been proposed as a foundation for the examination of tobacco use9-11. Despite this social-ecological underpinning, traditional tobacco prevention and control programs have focused on a smoker’s individual characteristics and have been criticized for lack of attention to social and contextual factors10,12. There is concern that failing to address these factors may partially explain the increasing class-based disparity in smoking behavior13. A gendered and contextual framework for tobacco disparities research has been advocated for use to help to explain the persistent tobacco use among low income rural women, in particular14-16.

Social and contextual factors are organized across multiple levels including individual, interpersonal, organizational (eg workplace) and neighborhood/community. As applied to tobacco use, individual factors include conditions such as socioeconomic status, daily stressors, and affective state13. Depression and stress are associated with persistent smoking12,17,18, and poorer smokers are more nicotine dependent13. Higher rates of smoking are associated with loneliness, and the relationship is more pronounced in environments where smoking is accepted19. Interpersonal factors can involve social networks, social support, social norms and social participation. A smoker’s social network is complex; often these networks include others who smoke, like family, friends and co-workers20. However, if social support to quit smoking is provided from family, friends or co-workers, there is increased likelihood of maintaining abstinence21. Similarly, social norms, such as the perception of whether others think one should quit smoking, have influenced cessation22. While tobacco use has gradually been denormalized in some regions of the USA (eg California), the social norms in other parts, like the rural Appalachian region, continue to promote smoking as normative23. High social participation is a predictor of maintaining smoking cessation24, although some studies have noted it to be associated with persistent smoking25. As an organizational factor, the workplace has the potential to offer support for behavior change. Worksite smoke-free policies and cessation services have decreased the prevalence of smoking among employees10,26. Among smokers employed in small firms, the workplace social network positively influenced quitting20. Neighborhood/community factors such as neighborhood level of social cohesion, or connectedness, are associated with lower neighborhood smoking prevalence27. Deprived neighborhoods have been targets for tobacco industry marketing, with poor residents disproportionately exposed to aggressive advertising of tobacco products28. Deprived neighborhoods are also less likely to be depicted by adequate social cohesive factors of trust, hope and reciprocity29.

As applied to the Appalachian region of Ohio, the social-contextual model of tobacco control and the potential mechanisms that may partially explain the maintenance or cessation of a smoking behavior among women have yet to be comprehensively studied. Further investigation of the model can inform an understanding of the behavior and offer guidance about the salience of future innovative tobacco prevention and control interventions. Individual factors such as age, socioeconomic position, depression, and early age at first pregnancy among disadvantaged smokers have received some attention 6,13. However, less is known about other factors embedded within a social-contextual perspective. As such, the purpose of this study was to determine the association of selected individual, interpersonal, workplace, and neighborhood characteristics with smoking status among women in Ohio Appalachian counties. These findings may assist in continued efforts to design and test scientifically valid tobacco control interventions among vulnerable groups.

Methods

Design, recruitment and procedure

This study, conducted from August 2012 through October 2013, used a cross-sectional survey design. Women, 18 years of age and older, who resided in three Ohio Appalachian counties, were eligible to participate. A two-phase address-based sampling methodology30 was modified and implemented. In brief, the US Postal Service listing of county household addresses served as the sampling frame from which a random sample of households was selected, by participating county, in batches of 50–100 for phase 1 household mailing. Phase 1 involved a mailed recruitment letter including a US$2 bill and one-page questionnaire requesting the household to enumerate and provide contact information for women aged 18 years and older. The household was instructed to return the completed enumeration questionnaire in a return-addressed stamped envelope included in the mailing. At weeks 3 and 6, additional mailings were sent to households not responding to the first mailing. The subsequent mailings included no additional monetary incentives. Once the enumeration questionnaire was returned, one eligible woman in each household was randomly selected for invitation to the study.

At phase 2, a field interviewer contacted the randomly selected woman to explain the study, confirm eligibility and invite participation. Once the woman agreed, an interview was scheduled at a convenient time and place (usually her home) where informed consent was obtained. Next, a face-to-face survey, which took about 60 minutes to complete, was administered by the interviewer. Each woman was given a $50 gift card for her time.

This two-phase recruitment process continued until 400 women were enrolled (the recruitment goal based on power calculations detailed elsewhere31).

Measures

The interviewer-administered survey included the following measures.

- individual factors: (1) sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, education, marital status, income, employment status); (2) Perceived Stress Scale18; (3) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale32; (4) loneliness33; and (5) smoking status (never, former or current) based on National Health Interview Survey categories34

-

interpersonal factors: (1) social networks including a time network, which asked the woman 'to identify up to 9 social ties with whom she spends the most time with in daily activity'; and an advice network, which asked the woman 'to identify up to 9 social ties the woman goes to for advice and feedback'. All social ties were eligible for nomination in both network measures. For both the time and advice network measures, the woman was asked to report the following information about her social tie: name; smoking status (non-smoker or current smoker); age (younger, older or same as woman); education (more, less or same as woman); current romantic or intimate partner (yes/no); and which nominated social ties knew each other.

(2) social norms, using van den Putte’s 6-item Social Influences Scale22, which characterizes verbal, behavioral, explicit smoking and quitting, injunctive and subjective norms, and number of persons regularly seen trying to quit smoking

(3) perceived social support, as measured by the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support35, which assesses partner, family, and friend support

(4) social participation, which considers past year engagement in activities such as church, sports, clubs, and service groups24 - workplace factors (if currently employed): presence of smoking policies that ban or restrict smoking to designated areas of the workplace36

- neighborhood/community factors: social cohesion as measured by perceived levels of neighborhood dependency, security, and trust37.

Data analyses

An egocentric analytic approach was used to structurally characterize social networks. This approach utilizes data collection from survey respondents about their social ties without interviewing the tie38. First, absolute size (0–9) and density (number of relationships among ties ÷ maximum possible number of relationships x 100)38 were computed. Density scores ranged from 0 to 1, with a score of 1 representing a network that is completely dense where all ties are linked (ie are reported to know each other). A density score of 0 represents a network where none of the ties are linked (ie not reported to know each other). Next, E/I social network index on smoking, or similarity of respondent with ties (ie homophily) on smoking status (number of ties with same smoking status as respondent ÷ total number of ties), was estimated and ranged from –1 to 1. An estimate of –1 means that all ties are the same as the respondent on smoking status (ie homophilous) and 1 reflects that none of the ties are like the respondent on smoking status (heterophilous). Finally, percentage of network ties who smoke, percentage of network ties the same age or older than the respondent, and percentage of network ties with the same or more education were calculated. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software v9.3 (SAS; http://support.sas.com/software/93).

Differential distributions of sociodemographic characteristics by smoking status were analyzed using χ2 and Kruskal–Wallis tests. To determine the association between selected individual, interpersonal (including social network), workplace and neighborhood/community-related characteristics and smoking status (categorized as never, former and current smoker), generalized linear models (using the generalized logit link) were fit using smoking status as the dependent variable and multilevel characteristics as reported by each woman as independent variables. To create a final multivariable multinomial logistic regression model, factors were entered into the model in four steps, in the order of individual, interpersonal, neighborhood and workplace level factors. Workplace level factors were entered last due to a small number of employed respondents. At each step, factors with p≤0.20 from the univariate analyses were included in the multivariable model. Backward selection was used to eliminate those factors with p>0.05.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (study ID: 2011C0041).

Results

Household enumeration packets were mailed to 1950 households in phase 1. A total of 776 households completed and returned enumeration questionnaires, while 201 households were deemed ineligible (195 whose mailing was returned undeliverable and 6 whose forwarding address was out of county), 30 refused enumeration, 17 returned incomplete questionnaires, and 926 did not respond. Based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research response rate 1 formula38,39, phase 1's household response rate was 44.4% (776/1749)30. After review of the enumerated questionnaires, 177 households were deemed ineligible for phase 2 participation because they contained no women. Of phase 1 responding households, 599 contained eligible women from which one per household was randomly selected and invited to participate in an interview. A total of 21 selected women were found to be ineligible, 116 refused to interview, 1 was unable to participate, and 53 were not able to be contacted. Subsequently, 408 women completed the survey, representing a 70.6% (408/578) participation rate for phase 230.

Sample characteristics

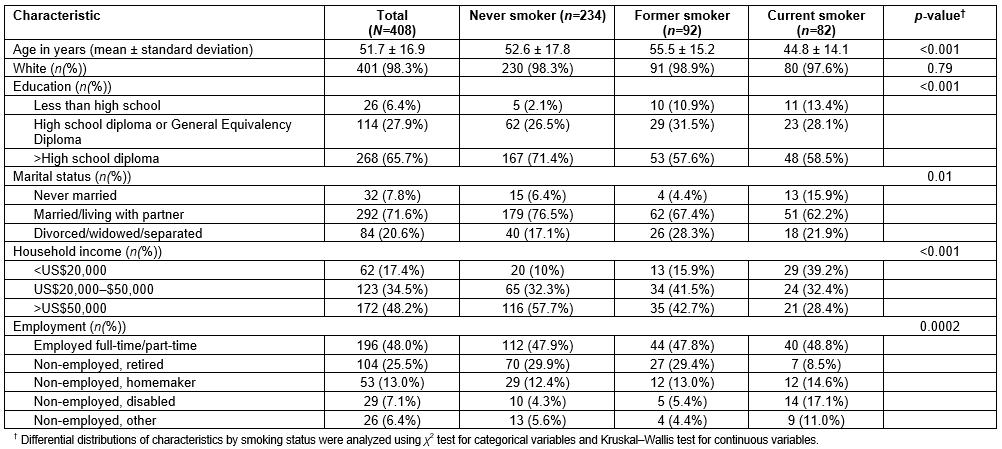

In Table 1, the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are presented for the total sample and according to smoking status. Participant age range was 18–95 (mean 51.7) years and most were married or living with a partner (71.6%). About two-thirds had more than a high school education (65.7%) and almost half were employed full- or part-time (48.0%) and had a household income of >US$50,000 (48.2%). The sample included 82 (20.1%) current smokers and 92 (22.5%) former smokers, with the remaining 234 (57.4%) reporting never smoking. Significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics were noted by smoking status. Current smokers were younger than never and former smokers (p<0.001), more likely to have never been married (p=0.01), and earned less income than never and former smokers (p<0.001). Distributions of employment status were different by smoking status, as well (p=0.0002). For instance, only 4.3% and 5.4% of never and formers smokers, respectively, reported non-employment due to disability, whereas 17.1% of current smokers did.

Findings

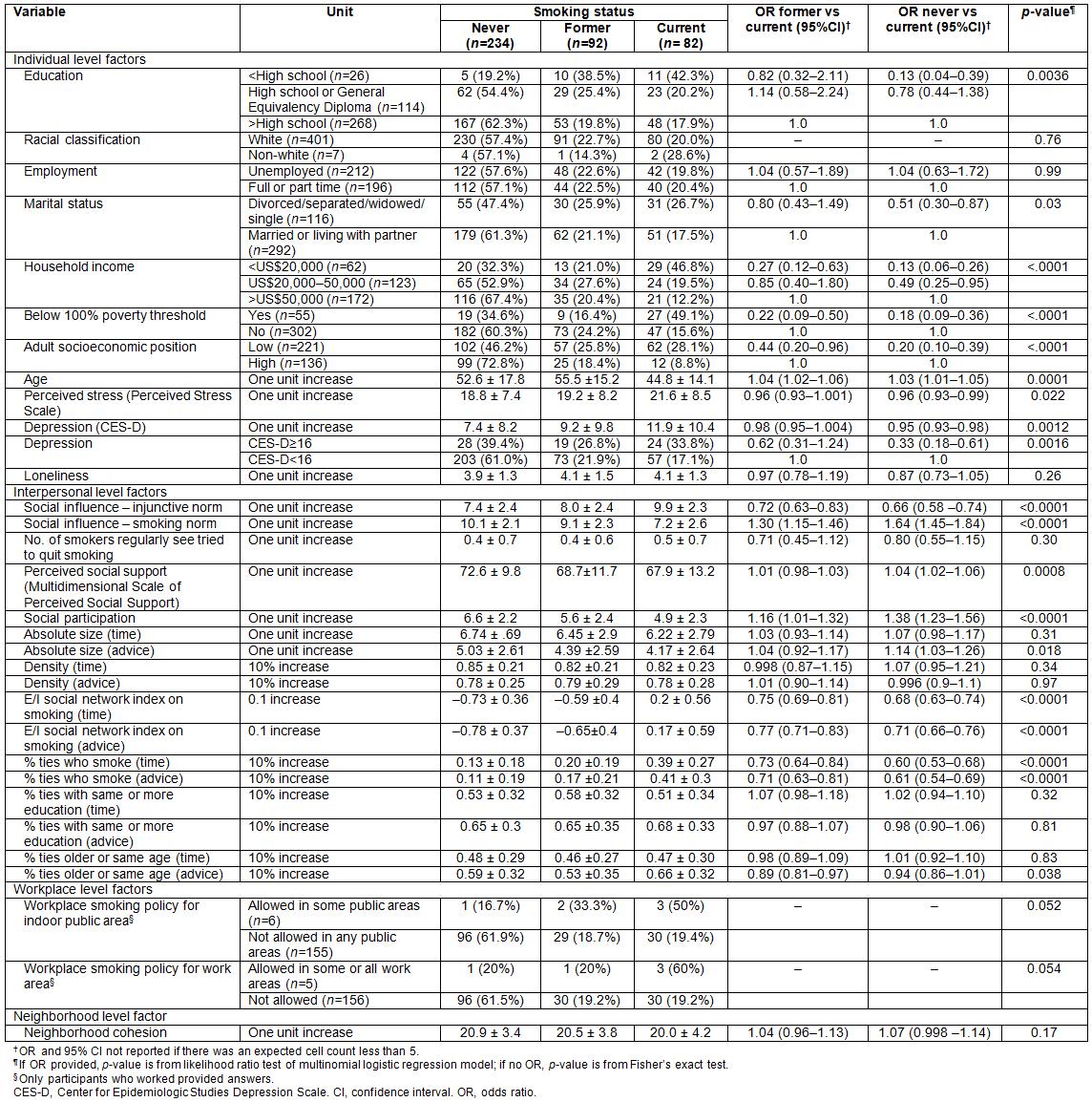

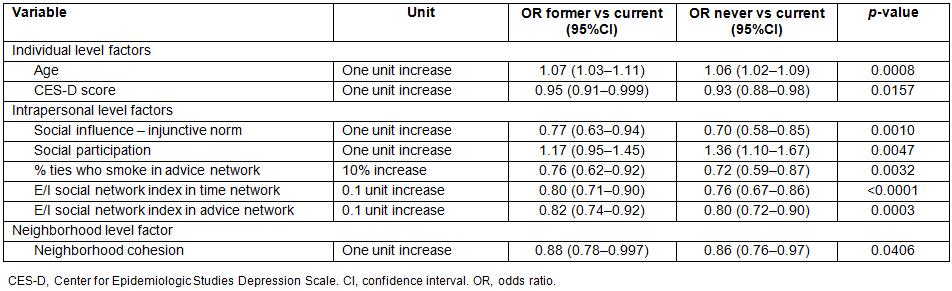

In Table 2, univariate multinomial logistic regression analyses results are shown. The analyses examined individual, interpersonal, workplace and neighborhood level associations between never and current smokers, as well as ex-smokers and current smokers. The final multivariable multinomial logistic regression model is presented in Table 3.

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics for total sample and by smoking status

Table 2: Univariate multinomial logistic regression analyses examining the differences between former versus current smokers and never versus current smokers

Table 3: Final multinomial logistic regression model that examined differences between former versus current smokers and never versus current smokers (n=383; 74 current smokers, 87 former smokers, 222 never smokers)

Individual factors associated with smoking status: Individual level factors significantly associated with smoking status in the final model included age and depression. For every additional year in age, the odds of being a former or never smoker increased by 7% and 6% (odds ratios (OR): 1.07 and 1.06), respectively, as compared to the odds of being a current smoker. With regard to depression, for each one unit increase in the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score, the odds of being a former or never smoker were 5% and 7% less (OR: 0.95 and 0.93), respectively.

Interpersonal factors associated with smoking status: Five interpersonal factors were associated with smoking status in the final model. As the social influence injunctive norm score increased by one unit, the odds of being a former or never smoker were 23% and 30% less, respectively, than the odds of being a current smoker. A higher injunctive norm score indicated that smoking is perceived to be more acceptable. Social participation was also associated with smoking status: for every one unit increase in the social participation score, the odds of being a former or never smoker increased by 17% and 36%, respectively. In terms of the percentage of social ties in the participant’s advice network who smoked, for every 10% increase, the odds of being a former or never smoker were 24% and 28% less, respectively. Homophily on smoking, or a participant’s similarity to her social ties, was also significantly associated with smoking status in both time and advice networks. Specific to the time network, for every 0.1 unit increase in the E/I social network index, the odds of being a former or never smoker were 20% and 24% less, respectively, than the odds of being a current smoker. Similarly, for the advice network, for every 0.1 unit increase in the E/I social network index, the odds of being a former or never smoker were 18% and 20% less, respectively. A higher E/I index indicated less similarity with social ties.

Neighborhood factors associated with smoking status: Finally, neighborhood cohesion, a neighborhood level variable, was significantly associated with smoking status. In the multinomial regression analysis, for every one unit increase in neighborhood cohesion score, the odds of being a former smoker or never smoker were 12% and 14% less, respectively, than the odds of being a current smoker. Higher scores are associated with greater neighborhood cohesion.

Discussion

This study’s findings add to the mounting evidence suggesting that reducing tobacco use among rural women will require moving beyond the individual to recognize that tobacco use and cessation behavior are intertwined with women’s social context16,40. Despite limited research elucidating social factors associated with smoking among low-income women living in rural settings41, study findings suggest that while controlling for individual factors, social constructs emerge as the predominant factors associated with smoking status for this vulnerable population.

Consistent with prior findings, younger age and depressive symptoms were associated with smoking among women in rural Appalachia6. This study contributes to the literature by documenting the social factors creating contextual vulnerabilities that might explain the disparate smoking prevalence among these women. Here, both stronger perceptions of the social acceptability of smoking and of neighborhood cohesion were associated with current smoking. Positive regard for one’s neighbors and belief that neighbors have the ability to come together to help each other is associated with never or former smoking in more privileged populations, and is generally regarded as an asset27; however, in this economically disadvantaged population, heightened neighborhood cohesion is a smoking liability. Among rural women, when strong neighborhood cohesion is coupled with a normative belief regarding the generalized acceptability of smoking, it appears that women’s sense of social connection may outweigh other factors facilitating smoking abstinence. The present findings are suggestive of the simultaneous importance of neighborhood support and anti-smoking norms, both of which could potentially be addressed with a multilevel cessation intervention.

As others have noted20, social network characteristics (ie percentage of social ties who smoke, homophily on smoking status within the network) also emerge as critical factors associated with smoking status for women residing in Appalachia. In this population, whereas non-smoking women’s social networks tend to be populated by other non-smokers, smoking women have a mixture of smoking and non-smoking network contacts31. Consequently, women embedded within social networks consisting of an increasing percentage of smokers are thereby more likely to be current smokers.

This study’s findings add to the mounting evidence of the central role of social context to smoking and cessation behavior among subpopulations of vulnerable women, in general. For instance, parental supervision in adolescence, church attendance in early adulthood, and maternal smoking influence current smoking for African-American women living in Chicago42. African-American women living in public housing in the same region have reported that managing daily existence in a stressful environment, social support, isolation, and the commonality of smoking are barriers to cessation43. For African-American women living in subsidized housing in two south-eastern US states, while stronger social cohesion was found to be associated with lower smoking, living in a neighborhood with higher social cohesion was not associated with smoking prevalence44. For women in Denmark and Finland, social network factors, including presence of smokers in women’s social networks, was central to smoking behavior45,46. Among Aboriginal women in Western Australia, smoking was seen as a stress reducer that helped women cope with social and economic pressures, and, therefore, was seen more for its benefit than for its detrimental health impact47.

Attention to restructuring or enhancing connection in social networks for smoking prevention and cessation has been suggested both during the postpartum period for women who quit smoking while pregnant and for sexual minority adolescent women48,49.

The present study was not without limitation. The goal was to recruit a representative sample of women in the Ohio Appalachian region based on smoking status – therefore, random selection was employed in the recruitment methodology. Response rates were similar to others using a two phase address-based sampling methodology, giving support for the use of this method to recruit a subpopulation of women in rural settings30. However, those households that initially responded to the enumeration survey at phase 1, and those women who agreed to participate in interview-administered surveys at phase 2, were probably meaningfully different from households and women that did not respond or agree to participate; consequently, the sample was more affluent and had less smoking prevalence than is representative in the region30. Non-response bias is of concern because it limits one’s ability to generalize findings to the population of interest50. In addition, the sample was primarily white; although representative of the local study region, this presents challenges for generalizability30. In addition to the limitations caused by representativeness, participants reported the smoking status of their network members, increasing potential for misclassification on key factors including smoking status. Finally, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data and the modeling methodology51, relationships between multilevel characteristics and smoking status cannot be interpreted as causal.

Disparities in tobacco use between privileged and vulnerable populations have increased due to differential rates in access and treatment response to existent tobacco cessation intervention13. The authors’ findings indicate that a more holistic, socially focused approach to tobacco control may be necessary to change the widening trajectory of smoking disparity for rural women9. In the Appalachian community, where women’s social connections are critically important, and where smoking may provide an avenue for both stress reduction and social acceptance within a peer group41, successful tobacco cessation programming for rural women may need to focus on 'social exchange' whereby the emotional and social benefits of smoking are acknowledged for their social value, addressed and replaced by other emotional and social benefits in the process of cessation16. While the findings suggest a need for cessation intervention components to target potential co-treatment of depression, they also indicate that a novel, women-centered cessation intervention for rural women would consider smoking behavior in context. Such an approach would acknowledge the critical importance of women receiving support for cessation from family and friends while working with women to determine how best to address cessation within the context of their individual and social vulnerabilities16,41.

Conclusions

This study’s findings indicate that a social-contextual approach to tobacco control may be useful for narrowing a widening trajectory of smoking disparity impacting rural women in the Appalachian region of the USA. Interpersonal context, in particular, must be considered in the development of culturally targeted cessation interventions for this population, and should be considered for other vulnerable women and rural populations worldwide.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (P50CA105632) and the Behavioral Measurement Shared Resource at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30CA016058). This project was also supported by a grant from the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences (USA) (UL1TR001070). Grant sponsors had no role in study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; article writing; or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.