Introduction

Hypertension accounts for at least 12% of total deaths and 3.8% of disability-adjusted life years worldwide1. Globally, more than 1 billion people have hypertension, of whom only 13% of these have their high blood pressure under control2. In Indonesia, the fourth largest population in the world, the prevalence of hypertension among those older than 45 years is more than 50%3. Given that high blood pressure is a significant risk factor for stroke, renal failure, heart attack and other cardiovascular events that can cause permanent disability and death4, optimal hypertension management is very important. In Indonesia, stroke is the leading cause of death, accounting for 15.4% of all deaths in 20075.

Hypertension management requires the use of anti-hypertensive medications and modification of lifestyle factors6. Long-term medication is usually needed to achieve blood pressure targets, and having access to an adequate supply of medicine is an essential step to facilitating medication adherence. However, the availability and affordability of medicines remains a big challenge in developing countries. A study conducted in an Indonesian community health centre (CHC) reported that there are limited supplies of anti-hypertensive medications7; provision for 3 days of medication supply is made available to each patient at a follow-up consultation in the CHC8.

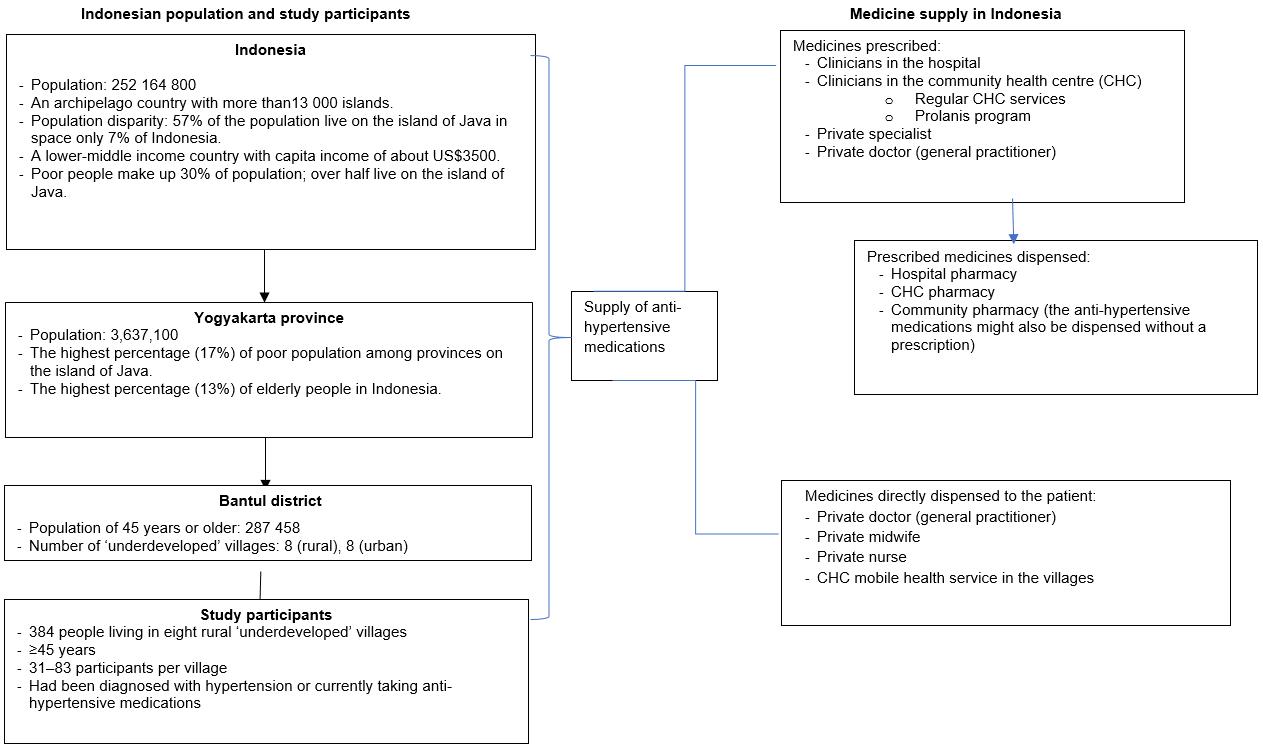

People in Indonesia have several sources of medicine (Fig1). In addition to CHCs (a public health service), Indonesian people widely utilise private providers (eg village doctors) to access healthcare services and medication9. Alongside the growth in the number of community pharmacies in Indonesia, self-medication practices are also increasing9. Although hypertension is a common condition among Indonesian people3, data regarding how people actually obtain their anti-hypertensive medications is scarce. This study, therefore, aimed to explore how and where people in rural villages in Indonesia obtain their supplies of anti-hypertensive medications. This study also reports the types of medicines obtained, and factors associated with obtaining anti-hypertensive medications from key sources of supply.

Methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study using a researcher-administered questionnaire was conducted in August–November 2015 in eight rural villages in the Bantul District, Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia.

Participant recruitment

The villages included in this study were selected based on data from the Bantul District government regarding underdeveloped villages in the district10. All rural underdeveloped villages in the Bantul district were selected. The minimum sample size per village was proportionally calculated based on the number of people aged 45 years or more in these villages. The study population and sample are described in Figure 1.

People were eligible for inclusion if they were villagers, aged 45 years or more, and had been diagnosed with hypertension by a healthcare professional or were currently taking medications for hypertension. Patients with cognitive impairment or severe hearing loss were excluded.

Participants were identified and contacted with the assistance of community (lay) health workers (CHWs). The CHWs distributed an invitational letter to the members of a community-based program, namely Integrated Health Service Post for the Elderly (IHSP-Elderly). People who attended a mobile health service in the village (conducted by a local hospital) were also invited to participate. Purpose sampling was used to identify potential participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria; therefore, gender representativeness was not determined before the study. Expressions of interests were collected by CHWs on behalf of the researchers. The CHWs served as the initial conduits of information between the participants and the researcher. Eligible participants were recruited until the sample size was attained.

The sample size for this study was calculated based on the point estimate of effect, defined as the proportion of patients with hypertension expected to be on anti-hypertensive medications in Indonesia (ie 63%11). Using the 95% confidence interval and 5% precision, 359 participants were required for this descriptive study.

Figure 1: Sampling frame and context for study (population data from Statistics Indonesia12).

Figure 1: Sampling frame and context for study (population data from Statistics Indonesia12).

Data collection

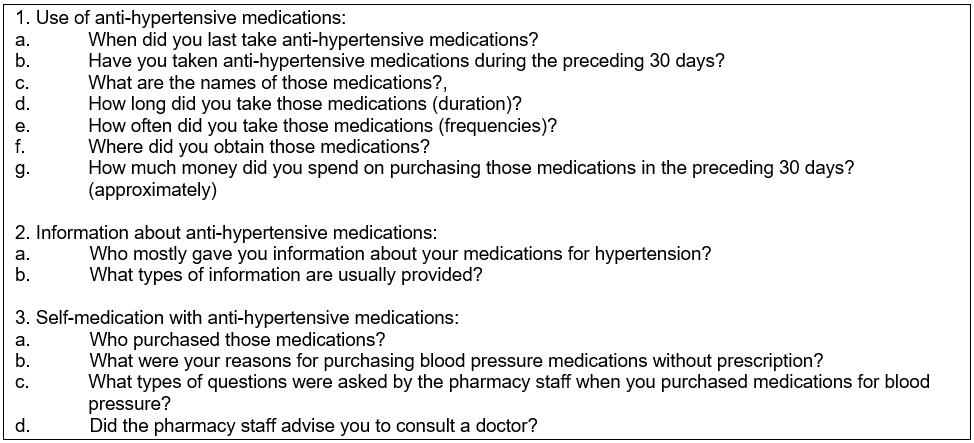

Using a researcher-administered questionnaire, the first author (who is Indonesian) conducted the interviews in each participant’s home (or another convenient location at the participant’s request). Each interview took 15–30 minutes to complete. The questions included sociodemographic data (eg age, level of education, current occupation), history of hypertension (eg years since diagnosis, place of diagnosis), the use of hypertension medications (Table 1), and the participant’s knowledge about hypertension. The short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire was used to guide questions regarding participants’ physical activity13. Based on the metabolic equivalent of task (MET)-minutes/week, level of physical activity was categorised into inactive (<600 MET-minutes/week), minimally active (600–3000 MET-minutes/week) and active (>3000 MET-minutes/week)14. Information about the types and names of anti-hypertensive medications was verified from the blister pack (medicine packaging) if the participant had this available during the interview. A standardised instrument from a previous study was used to assess hypertension knowledge15. It comprised 10 questions with a score of 1 for each correct response. Good knowledge was defined as a score of 8 or more.

Table 1: Questions for participants to explore access to medicines for hypertension in rural Indonesia

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v23.0.0 (IBM; http://www.spss.com) was used for data entry and analysis. Descriptive statistics are presented to characterise the study participants. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical data between groups, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to continuous data. When more than 20% of expected frequencies were less than 5, Fisher's exact test was used. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The significance values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for multiple analyses.

Ethics approval

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee, University of Technology Sydney (ref. no. 2014000647). Approval from the Bantul district office was also granted (ref.no. 070/Reg/0558/S3/2015)

Results

Characteristics of participants

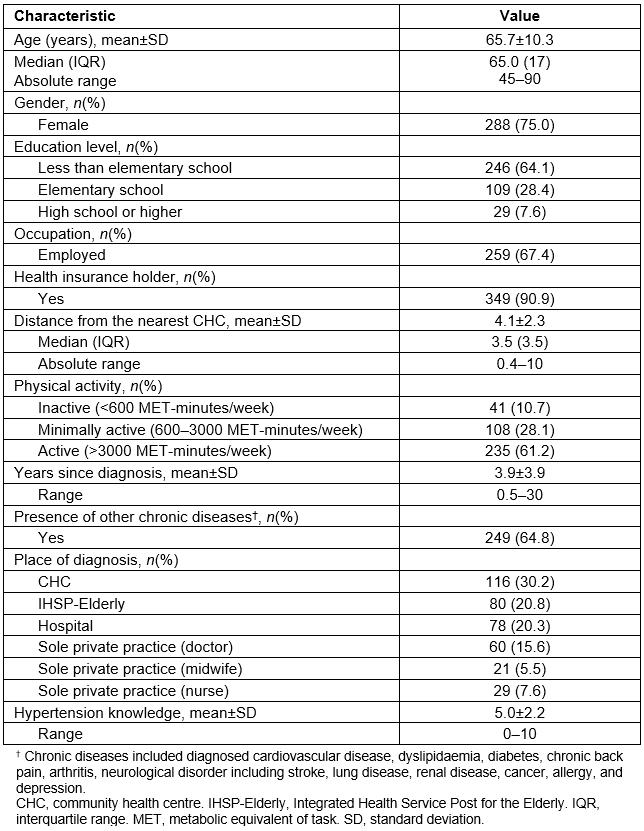

Three-hundred and eighty-four participants completed the survey (Table 2). As per the study criteria, all participants were aged 45 years or more; their mean age was 65.7±10.3 years (range 45–90 years). Most of the participants were female (75%). The vast majority had a low level of education: only 29 (7.6%) had completed at least high school. About one-third (32.6%) were unemployed, and farmers predominated (73.4%) among the employed participants. Most participants (61.2%) were physically active while 28.1% and 10.7% were minimally active and inactive, respectively. Almost all (n=349, 90.9%) had health insurance, and 339 (88.3%) were recipients of government healthcare insurance for poor people16.

Diagnosis of hypertension

As self-reported by participants, the average time since diagnosis of hypertension was 3.9±3.9 years (range 0.5–30 years). Table 2 shows that over half of the 384 participants (n=196, 51%) were diagnosed by the CHC staff, followed by private clinicians (n=110, 28.7%) and hospital staff (n=78, 20.3%).

Table 2: Characteristics of participants (n=384) (MET-minutes/week calculated based on International Physical Activity Questionnaire protocol13,14. Assessment of hypertension knowledge was adapted from a previous study15).

Source of anti-hypertensive medication supply and associated factors

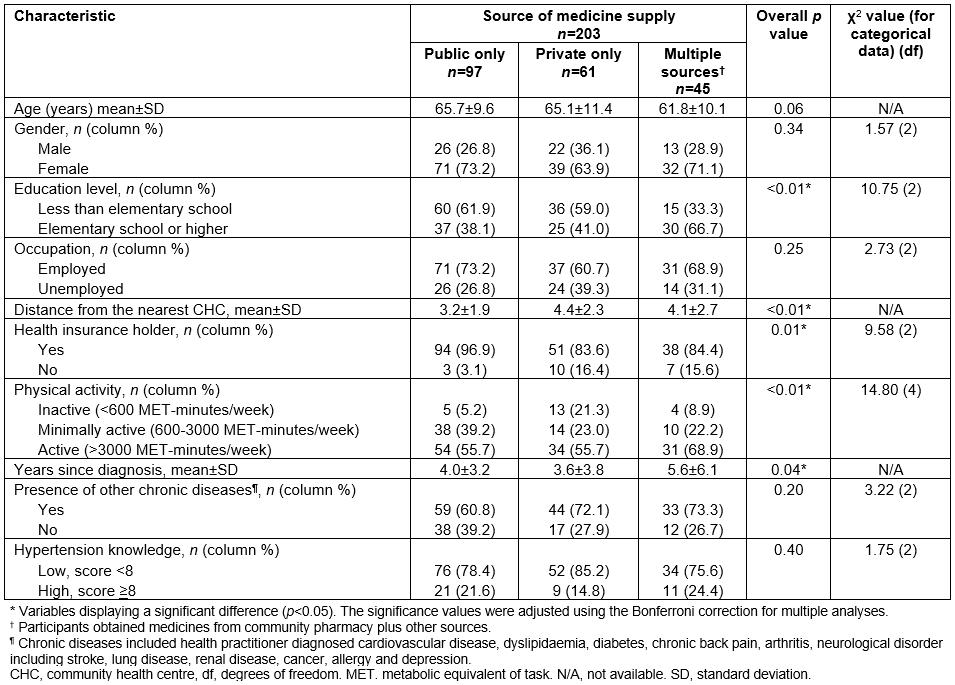

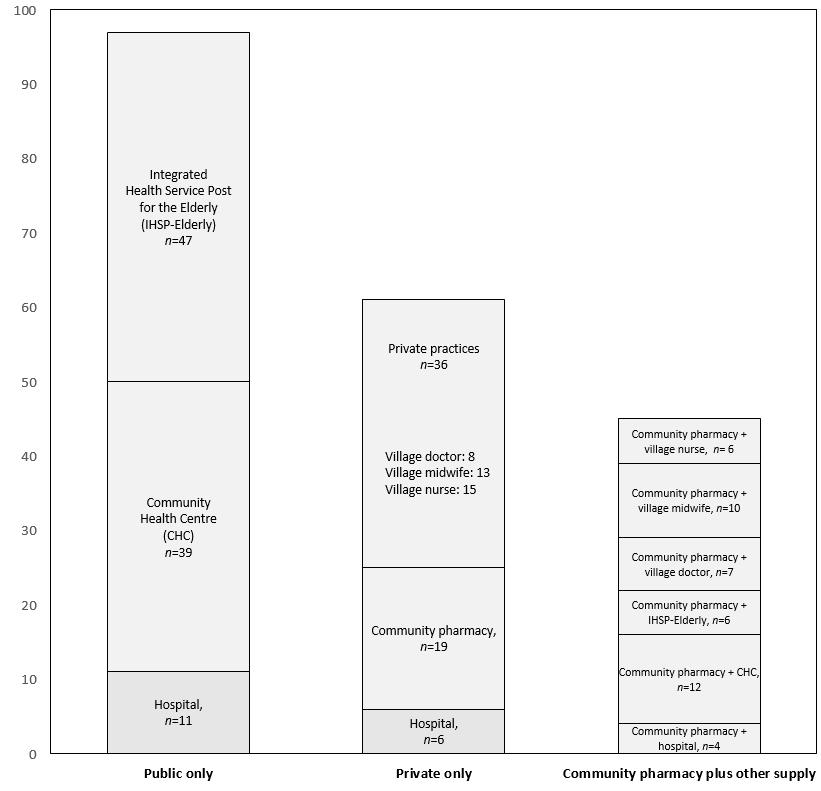

Responses to the question ‘Where did you obtain your anti-hypertensive medications within the previous 30 days?’ were collected from 203 participants who reportedly took at least some quantity of hypertension medication during the period. Participants were categorised into three groups (Table 3) based on where they obtained their medicines: ‘public only’, ‘private only’, or ‘multiple sources’. Almost half (n=97) had obtained their medicines solely from the public health services (CHC, IHSP-Elderly, public hospital) while 61 (30%) participants obtained them solely from the private healthcare providers such as a private hospital, community pharmacy (CP), or private practice (doctor, midwife, nurse). Other participants (n=45, 22%) reported multiple sources of medicines, such as from a CP and a CHC (Fig2).

Overall, participants within the three ‘sources’ groups differed significantly in terms of educational level (p<0.01), distance from the nearest CHC (p<0.01), medical insurance status (p=0.01), physical activity (p<0.01), and years since diagnosis (p=0.04) (Table 3). There were no significant differences across the groups in age, gender, employment status, presence of other chronic diseases, or hypertension knowledge (Table 3). Applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests showed that participants in the ‘multiple sources’ group had a higher level of education than those in the ‘public only’ or ‘private only’ groups. Participants in the ‘public only’ group lived a shorter distance from the CHC than those in the ‘private only’ group. Participants in the ‘multiple sources’ group had been diagnosed with hypertension for a longer period of time than those in the other two groups; however, the differences between groups were not significant. A higher percentage of participants had medical insurance in the ‘public only’ group than in the ‘private only’ group or ‘multiple sources’ group. The percentage of patients with a low level of physical activity was higher in the ‘private only’ group than in the ‘public only’ or ‘multiple sources’ groups.

Anti-hypertensive medications were obtained most frequently from a CP (32%), followed by IHSP-Elderly (26%), CHC (25%), village midwife (11%), village nurse (10%), hospital (10%), and village doctor (7%). Participants obtained their anti-hypertensive medications in three major ways: purchasing them from the CP (self-medication), obtaining the medicines directly from the clinicians (direct dispensing), and obtaining them freely from public healthcare services.

Table 3: Source of anti-hypertensive medication supply within preceding 30 days

Figure 2: Self-reported source of anti-hypertensive medication supply (n=203).

Figure 2: Self-reported source of anti-hypertensive medication supply (n=203).

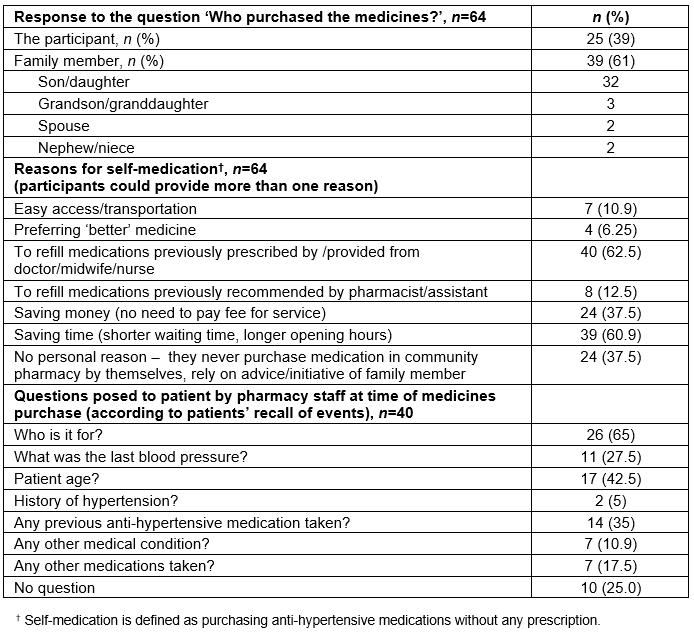

Purchasing anti-hypertensive medications from the community pharmacy: Instead of obtaining medicines on prescription, 64 (31.5%) participants obtained their anti-hypertensive medications over the counter from a CP, by simply mentioning its name, showing the tablet packaging, or asking for suggestions from the CP staff.

The most common reason for purchasing medicines without a prescription was the desire to continue the medication previously obtained from the clinician (n=40, 67.5%). Five participants (8.3%) claimed to have disclosed this practice to a doctor, midwife, or nurse, and gained their approval. A further eight participants (12.5%) reported that CP staff recommended to them the type of anti-hypertensive medications (Table 4). These eight participants had previously been diagnosed with hypertension by a clinician (doctor, midwife, or nurse); none of them had their hypertension diagnosed by CP staff. Of the 64 participants, 39 (60.9%) preferred to obtain medicines from a CP because it had more flexible opening hours and shorter queuing times compared with public healthcare services (eg CHC or IHSP-Elderly). Twenty-four participants mentioned avoidance of doctors’ consultation fees as a reason for bypassing appointments to obtain a prescription or supply from their clinician, and they instead purchased over-the-counter anti-hypertensive medications.

Interestingly, 39 of 64 participants (61%) did not personally attend a CP within the preceding 30 days, but rather had a family member (usually a son or daughter) purchase the anti-hypertensive medications on their behalf (Table 4). Twenty-four participants reported that they had never attended the CP to purchase their anti-hypertensive medications. Therefore, only 40 of 64 (62.5%) participants were able to provide information about the type of questions posed by CP staff at the point of purchasing medications. Of these 40 participants, 26 (65%) recalled being asked by CP staff ‘Who is the medicine for?’ Other questions asked included the patient’s age (n=17, 42.5%), information about previous medicine used (35%), last blood pressure reading (27.5%), other medications taken (17.5%), and other medical conditions (10.9%). Only four participants (10%) claimed that they were advised by CP staff to consult a doctor. Ten participants (25%) reported that they simply purchased anti-hypertensive medications without any questions from CP staff (Table 4). It is important to note that none of the participants could recall whether a pharmacist or pharmacy technician had served them in the pharmacy.

Table 4: Features of the practice of purchasing anti-hypertensive medications (without prescription) in Indonesian community pharmacies

Obtaining medicines directly from clinicians (direct-dispensing): Fifty-nine participants (29%) reportedly received their anti-hypertensive medications directly from their clinicians – direct dispensing from a doctor (n=15), midwife (n=23), or nurse (n=21). The clinicians did not write prescriptions but instead dispensed medications in the consultation room, and charged patients a fee for the consultation and medications. Participants reported spending A$3–5 for each visit to a private practice. The total cost paid to a village doctor was higher than that to a midwife or nurse (Table 5). To provide a comparison, the monthly minimum wage for people in Yogyakarta province in 2014 was A$98 or an hourly rate of about A$0.512.

The participants cited clinical symptoms (severe headache, dizziness, light-headedness, and blurred vision) as hypertension-related symptoms that were reasons for visiting a private practice. Participants who preferred to obtain their medications from a private practice rather than from other healthcare providers cited their reasons as having an established relationship with the clinicians, experiencing satisfactory services, and believing that treatment in a private practice was better than in public facilities (eg CHC).

Obtaining a free supply of medicines from public healthcare services: More than half of the treated participants (n=119/203, 58.6%) obtained their medicines at no cost by visiting public healthcare services such as the IHSP-Elderly (n=53), CHC (n=51), or public hospital (n=15). In the IHSP-Elderly, healthcare services were performed by the CHC health staff members (midwife or nurse). The frequency of these services offered in the villages ranged from once a month to once every 3 months.

Among those participants who obtained their medicine supply from a CHC, 14 noted that they had joined a comprehensive program to manage chronic diseases in a primary healthcare setting, namely Prolanis, in the 1–2 months prior to the interview. Members of the Prolanis program were scheduled for monthly review at the CHC to have their blood pressure checked and managed. This program implementation was covered by the national health insurance scheme17. Participants who joined this program were funded mainly by the government-based insurance for poor people.

Table 5: Participants’ use of anti-hypertension medications across the various sources of supply

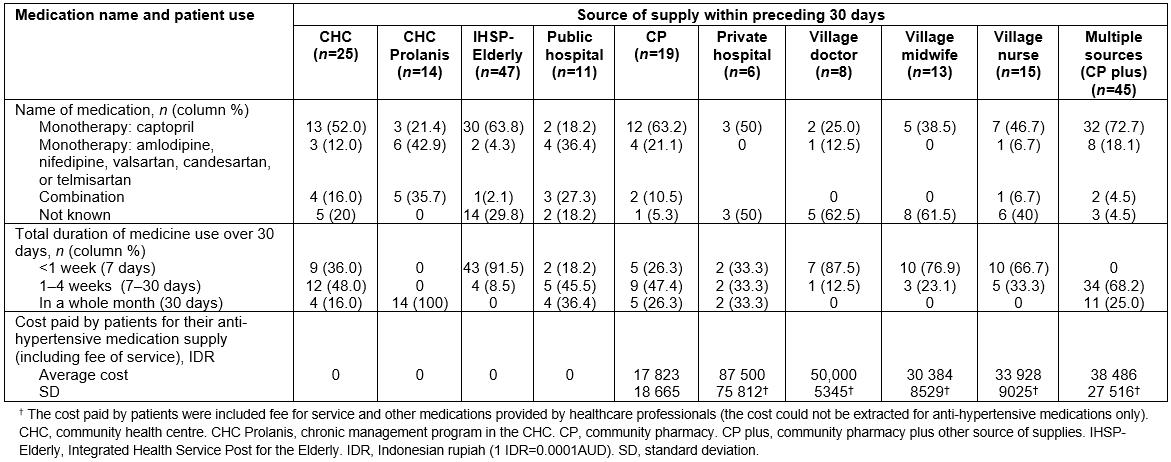

Type of medicines taken

Of 203 participants, 138 (68%) reported taking only one type of anti-hypertensive medication (monotherapy). The angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitor) captopril was most frequently taken (53.7%), followed by calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, nifedipine). Eighteen participants (8.9%) took a combination of anti-hypertensive medications including ACE inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker (n=14), calcium channel blocker plus angiotensin II receptor antagonist (n=2), calcium channel blocker plus beta-blocker (n=1), or ACE inhibitor plus beta-blocker (n=1).

Participants purchased captopril, amlodipine, nifedipine, or bisoprolol without prescriptions in CPs. Five participants who took angiotensin II receptor antagonists (valsartan, candesartan, telmisartan) obtained their medicines from the hospital. Of 21 participants who obtained medicines from the hospital, most (86.7%) had other chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, peptic ulcer disease, and stroke.

The type of anti-hypertensive medications could not be verified for 47 (23.1%) participants because they did not have a supply of their medicines available at time of interview and could not recall its name (Table 5).

Medicine use over the preceding 30 days

Among all participants, only 40 (10.4%) had taken anti-hypertensive medications every day for the preceding 30 days (Table 5). Most participants who obtained their medications from the IHSP-Elderly, village doctor, village midwife, or village nurse conveyed that the medications provided would last for only 3–5 days.

All participants who were Prolanis members (n=14) obtained a 30-day supply of medicine from the CHC (until their next visit to the CHC). By contrast, non-Prolanis members obtained anti-hypertensive medications for less than 30 days at each visit. Four non-Prolanis members who took their medications for the entire 30 days reported that they needed to visit the CHC three or four times in a month to refill their prescription. Five of the 19 participants who purchased anti-hypertensive medications solely from a CP reportedly took their medicines for the entire 30 days. All five participants were government insurance holders and had other chronic diseases (stroke, arthritis, dyslipidaemia, peptic ulcer disease). Medicines for treating these other diseases were also purchased in the CP without a prescription.

Discussion

This study reported various sources of supply of anti-hypertensive medications for patients in Indonesia. Overall, it included purchasing medicines over the counter in a CP, direct dispensing from private clinicians, obtaining a free supply from the public health service, or a combination of these sources of supply. Despite an awareness of having been diagnosed with hypertension, almost half of the participants had not taken anti-hypertensive medication during the preceding 30 days. This finding supports a previous study reporting that a low proportion of Indonesian people with hypertension take their medication11, and raises concerns about the risk of death and disability attributed to untreated hypertension1,4.

The quantity of anti-hypertensive medications obtained over the previous 30 days varied according to the source of supply, but almost half the number of patients obtained a supply of medicines that was sufficient for less than 7 days. Interestingly, inadequate supplies were provided by both the public health service (eg CHC) and private providers (eg village doctor). The limited supply of medicines from Indonesian CHCs has been reported previously7,8 and indicates that there is a need to review the CHC policy regarding the provision of medicines (number of days’ supply) to each patient at each health visit. Even though the standard treatment guideline for Indonesian CHCs states that up to 30 days’ supply of anti-hypertensive medications could be provided at each visit, the 30 days’ supply was provided only for patients who joined the Prolanis program, a new comprehensive approach under the universal health coverage scheme, which is expected to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events caused by hypertension and diabetes17. At the time of the present study, the Prolanis program had enrolled only about 50 members (patients) per CHC. Further studies are needed to explore the barriers associated with the implementation of the Prolanis program such as identifying the challenges in recruiting patients. The limited number of Prolanis members per CHC may be associated with the existing challenges within the healthcare services in rural areas such as the shortage of doctors and pharmacists18, poorly defined boundaries relating to the scope of authority between health professionals in the CHC19, and the lack of infrastructure. Further, as CHCs are the main primary healthcare system in Indonesia20, there is a need to strengthen the CHC capacity to provide accessible and affordable medicines. Indeed, facilitating adherence to anti-hypertensive medications is remarkably difficult when only 10% of patients receive an adequate supply of medicine. Even though the Indonesian government has standardised the medication distribution system for primary health care21, studies22,23 have indicated the need to improve its implementation to ensure the availability of medicines in CHCs and to promote rational use of medicines.

Other important aspects to improve the provision of health care for patients with hypertension in the CHC include providing a flowchart to guide the management of hypertension and facilitating a team-based approach in primary health care24,25. Despite the availability of updated international guidelines on hypertension (eg National Heart Foundation Guidelines in Australia26), they might not be easily implemented in low-resource settings such as rural Indonesia. For example, the ability to conduct cardiovascular risk assessments for hypertension patients as recommended by the Australian guideline26 is limited by the lack of the infrastructure in the primary healthcare setting27. This study shows that a substantial proportion of participants obtained their medications from CHW-based programs. Highlighting the potential of CHWs to support patients with hypertension in rural areas28, this finding indicates the need to encourage the role of CHWs, as part of the primary healthcare team, in assisting patients in rural areas to obtain adequate supply of medicine.

Patients who were not in the Prolanis program did not obtain a 30-day free supply of anti-hypertensive medications and therefore needed to proactively seek multiple sources for their supply of medicines. A substantial proportion of participants obtained their anti-hypertensive medications by purchasing them without a prescription; they sought an additional personal supply once they had no more medicines. This study showed that patients could easily purchase their anti-hypertensive medications in a CP, bypassing the need for an appointment with their doctor. Previous studies have also reported this self-medication practice in Indonesia and other developing countries29,30. The participants in this study acknowledged their perceived benefits of self-medication with anti-hypertensive medications from the CP. For instance, the patients who did not get an adequate supply from other sources (eg village doctor) preferred to go to a CP to refill their medicines as it was cheaper and more time efficient.

Given that the CP is the most common point of care for patients with chronic disease31, pharmacists play an important role in assisting patients in their medicine use. The potential of pharmacist-led interventions to improve medication adherence and blood pressure control has been reported32,33. A recent study among Indonesian community pharmacists reported positive attitudes toward their role in hypertension management, which included assessment and documentation; treatment recommendations; counselling; and monitoring of BP reading, side effects of medication, and complications29. To improve the medicine information provided to patients, reports of the lack of information gathering by pharmacists about self-medication34 need to be addressed through educational, managerial, and policy approaches. For example, an Australian study reported the effectiveness of a comprehensive training program for pharmacy staff to improve hypertension management35. Given the reported purchase of anti-hypertensive medications by family members (without the patient being present) in this study, the medicine purchaser should be informed of the drawbacks of such a practice in order to minimise the inappropriate use of medicines and delayed clinical evaluation36. Studies in Australia and Saudi Arabia have reported that other interventions, such as monitoring blood pressure in the pharmacy, are also appreciated by patients37,38, but can only be performed with the patient present.

Obtaining anti-hypertensive medications directly from a private practice was reported in this study. Overall, direct dispensing by clinicians is commonly practised in Indonesia9. According to Indonesian law, private doctors in rural areas, or in areas with limited access to a pharmacy, are allowed to dispense medication39. Given the high population demand and shortage of doctors, non-doctor clinicians (midwives or nurses) are also allowed to provide healthcare services for the general population (beyond their main competency)9,40. It was reported that some Indonesian patients cannot differentiate between clinicians, whether they are a doctor, midwife, or nurse19. In this study, prescribing and direct dispensing were provided by village doctors as well as midwives and nurses, such that patients did not need to visit a pharmacy to obtain medicines. The reasons why patients preferred to obtain medicines directly from the clinicians might be related to the difficulty in accessing medicines from other sources. Further, given that patients needed to purchase their medications out-of-pocket, affordability might also influence the patients’ decision not to refill their anti-hypertensive medications41. Patients opt to purchase medications that they can afford. This study also found that having health insurance was associated with obtaining medicines from the public health service. This finding is not surprising because most participants in this study were recipients of a government insurance scheme for poor people; the scheme does not cover medications obtained from a private clinician or CP.

Overall, these findings are noteworthy because the participants were derived from a community setting rather than healthcare centres, which provides an opportunity to obtain data from untreated patients who rarely visit healthcare providers. However, this study had some limitations. First, the potential bias (eg forgetfulness) associated with the reliance on self-reported data. Second, this study was undertaken in only one district; the results of this study may not be representative of the whole Indonesian population. Third, more females than males joined this study, which may limit the generalisability of the findings. This might be related to the fact that members of CHW-based programs, as well as villagers who attended mobile health services, were mostly women, which may have encouraged the recruitment of more females. However, the findings do reflect the practice in Yogyakarta province as well as other settings with a similar social context.

Conclusion

These Indonesian participants obtained their hypertension medications from various sources; however, the inadequate supplies found in this study could compromise both short- and long-term management of hypertension. Direct dispensing, non-doctor prescribing, and self-medication with anti-hypertensive medications indicate the current complex healthcare system in Indonesia. This study also shows some challenges involved in managing patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension in resource-poor settings. It provides important findings for quality improvement practices that should be considered to improve the health lifespan in populous countries such as Indonesia.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participation of all participants in the study. The authors are also thankful to all community health workers in the villages for their assistance during the study.