Introduction

The quantity and distribution of the health workforce, an important aspect of healthcare systems, directly influences the quality and quantity of health services and the development of medical systems1. Health workers play a central role in ensuring the appropriate management of all aspects of the health system2. In China, the distribution of the health workforce has changed a lot through medical system reform3. Different policies and interventions have resulted in inequitable distribution of the health workforce4. The paucity of qualified health workers in rural areas is a critical challenge, and has been a national concern in China5. The gap between the demand and the provision of basic health services remains substantially high partly due to a shortage of qualified health workers, particularly doctors, especially in rural and remote areas in western China.

Gansu province is a typical region in western China. Gansu (area 453,700 km2, population 25.99 million, including 43.19% urban residents and 56.81% rural residents, and GDP per capita US$4208.07 in 2015) is a largely agricultural province located in the Upper Yellow River Valley. It ranks about 26th among the 31 provinces in terms of health resources6. There is one health worker for every 108 people in the cities and only one for every 584 people in rural areas7.

In 2010, the Chinese government developed the reform policy on Primary Care Health Team Construction Planning with Emphasis on the General Practitioner8. In this planning, Gansu province has been selected as one of the most important pilot areas. With the support of the Chinese Ministry of Finance, Lanzhou University and Gansu University of Chinese Medicine offered preference for admission to students with rural origins. According to the policy, a certain number of medical students may get full financial support during their undergraduate study and further formal training in provincial hospitals for grassroots medical and health work. Accordingly, they are obligated to serve in the township-level hospitals designated in rural communities for at least 6 years after graduation in exchange for having their tuition fee waived during their 5 years of undergraduate medical education and 3 years of standard training9. The policy aims to recruit the applicants who are senior high school graduates of rural origin. The applicants apply voluntarily and must have completed the Chinese Ministry of Education state examinations for entrance of medical university with a qualified score. The applicants are accepted in accordance with the order of the scores from high to low, to match quota restrictions.

Based on the contract, the policy includes other issues, such as providing bursaries, scholarships, allowances linked to future practice rural location, adequate professional support, and help with re-employment while completing the 6 years working in rural areas.

Students’ attitudes, during their stay in medical school, towards training and medical practice could influence their future practice of medicine10,11. Many factors may influence the attitudes of medical students and their subsequent practice after graduation. Rural background has been shown in many different countries to be a determinant associated with medical graduates’ intentions and preferences to practise in rural settings12,13.

The policy has seemingly received an active response: 1990 applicants were recruited during the years 2010– 2015 in Gansu province. Until recently, little has been known about their real attitudes towards rural medicine work and the factors influencing these medical undergraduates’ decisions to work in rural areas under the selective admission policy.

The survey described in this article aimed to analyse the policy from the perspective of students’ attitudes towards rural career choice. It is helpful for policymakers to evaluate the selective admission policy scientifically, and to pay close attention to external system circumstances as well as personal internal factors in the process of ongoing healthcare reform efforts.

Method

Subjects

Undergraduate medical students were recruited by cluster sampling from the Medical College of Lanzhou University and Gansu University of Chinese Medicine. Their time of college enrolment was from 2010 to 2015 in Gansu, China. They majored in western medicine (WM) or traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) respectively in a 5-year undergraduate program under the selective admission policy. Study participants must have had rural household registration in the population management system in China and have had a rural background (lived in a town, county or village). A total of 1133 undergraduates were included in this study. Those who were not in survey sites during the investigation or refused to report were excluded.

Data collection

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among the study participants during November 2015 and January 2016. Data collected, using an anonymous questionnaire and face-to-face interviews, included sociodemographic characteristics, majors (WM and TCM), family background (annual household per capita income, any one member of immediate family engaged in rural medical, single child), entrance scores and contributing factors to rural medical career choice including all motives for applying for selective admission policies.

One concept considered in this article, ‘intrinsic motivation’ comes from individual inner desire or purpose, which indicates initiative. Another concept, ‘extrinsic motivation’, is a desire or purpose initiated from beyond the self, which indicates passivity. In this article, possible motivation items affecting the attitudes towards rural medical career choice partly reference to known factors14-16. Considering China’s national conditions and reality, other new items were added through pre-investigation by unstructured interview among medical undergraduates and rural general practitioners as well as rural workforce agencies in Gansu province.

Attitude scores

Overall attitude towards rural medical career choice was considered to be the total attitude scores based on the answers to all the survey questions, which were translated as statements of intrinsic motivation or extrinsic motivation. The attitudes were divided into two dimensions: personal attitudes and external attitudes (intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation). The degree of influence of the different dimensions was evaluated. The evaluation between the two dimensions was measured by ratio of scores between personal attitudes and external attitudes. The ratios (>1, 1, and <1) represented the preference of undergraduates’ independent decisions to work in rural areas.

Further analysis of factors influencing the preference of undergraduates’ independent decisions, including demographics, course majors, family backgrounds and entrance scores, was conducted. All statements of motives were transformed from survey questions. For the external performance of motivations, attitudes were represented by scoring answers using five-point Likert scale categories (‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘not sure’, ‘agree’, ‘strongly agree’). Responses were assigned a score from 5 to 1 or from 1 to 5 based on the degree of positivity about the content of each answer contributing to rural medical career choice.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted using mean and percentage, and inferential statistics were performed by χ² test for categorical variables of single-factor analysis, unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA for continuous variables of single-factor analysis. Ordinal logistic stepwise regression was applied to analyse the association between independent variables and orderly multi-classification dependent variables, and to screen statistically significant independent variables. A p-value less than 0.05 was used as the level of statistical significance. EpiData v3.2 (http://www.epidata.dk) was used for data inputting and database building. SAS v9.0 (http://www.sas.com) was used for quantitative data analysis.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Lanzhou University Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Participants and their attitudes towards rural medical career choice

A total of 1133 participants with a mean age of 22 years in this study were selected from 1990 undergraduate medical students in the selective admission policy, including 622 students majoring in WM and 511 students majoring in TCM. The percentage of males (45.6%) was lower than that of females (54.4%).

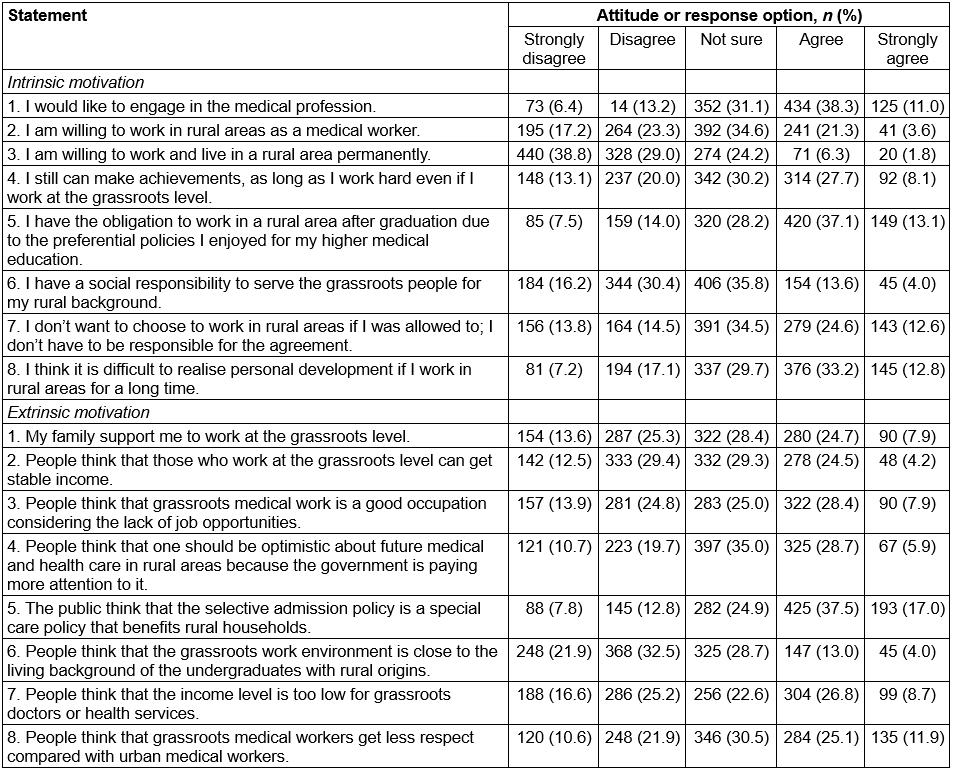

Table 1 shows the distributions of the participants’ responses for motivations statements related to contributing factors on attitudes of rural medical career choice. From the statements of intrinsic motivation, for the positive statements the highest rate and the lowest rate of positive attitudes were 50.2% (sum of ‘agree’ rate and ‘strongly agree’ rate of answers to the fifth statement) and 8.1% (sum of ‘agree’ rate and ‘strongly agree’ rate of answers to the third statement), respectively. For the negative statements, 37.2% (sum of ‘agree’ rate and ‘strongly agree’ rate of answers to the seventh statement) of the students agreed that they would not to choose to work in rural areas after graduation if the breach of contract were allowed, whereas the sum of ‘disagree’ rate and ‘strongly disagree’ rate only accounted for 28.3% of responses. A total of 46.0% of the students thought that it was difficult to realise personal development if they worked in rural areas for a long time (sum of ‘agree’ rate and ‘strongly agree’ rate of answers to the eighth statement), and 24.3% students disagreed with this (sum of ‘disagree’ rate and ‘strongly disagree’ rate to the eighth statement).

In the dimension of extrinsic motivation, the rates of positive attitudes had a range of 17.6–54.5% for the positive statements (sum of ‘agree’ rate and ‘strongly agree’ rate of answers to the sixth and the fifth statements). For the negative statements, 35.5% of students accepted this popular idea that they would plunge into low-income groups and 37.0% of them agreed with the public opinion that they would move into low social status groups once they worked in the countryside (sum of ‘agree’ rate and ‘strongly agree’ rate of answers to the seventh and eighth statements). A total of 41.8% and 32.5% of the students disagreed with the two negative opinions, respectively. Whether intrinsic motivation or extrinsic motivation, the rates of ‘unsure’ attitudes were considerable, which accounted for 22.6–35.8%.

Table 1: Participant responses for each statement of motivation related to rural medical career choice

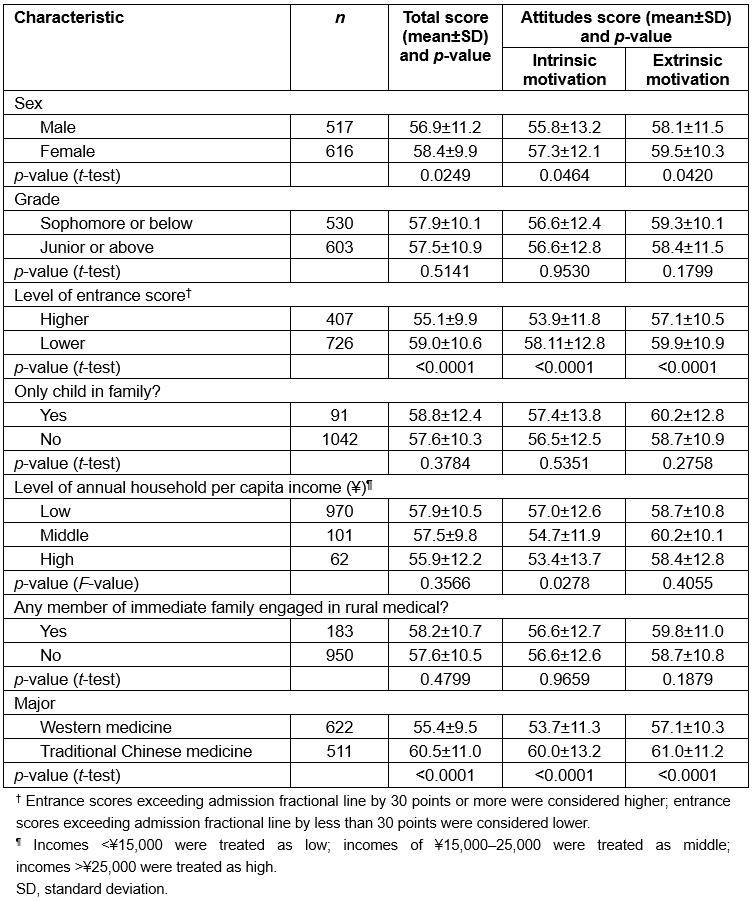

Attitudes scores and distribution of relative ratios of attitudes scores for different backgrounds

Attitudes scores based on intrinsic motivation were in a score range of 53–60, attitudes scores based on extrinsic motivation had a range of 57–61 and the total score had a range of 55–61 (using the centesimal system). The results with statistical significance through single-factor analysis indicated that girls had higher survey scores than boys, students with high entrance scores got higher survey scores and that students who majored in TCM got higher survey scores than those majoring in WM(p<0.05; Table 2).

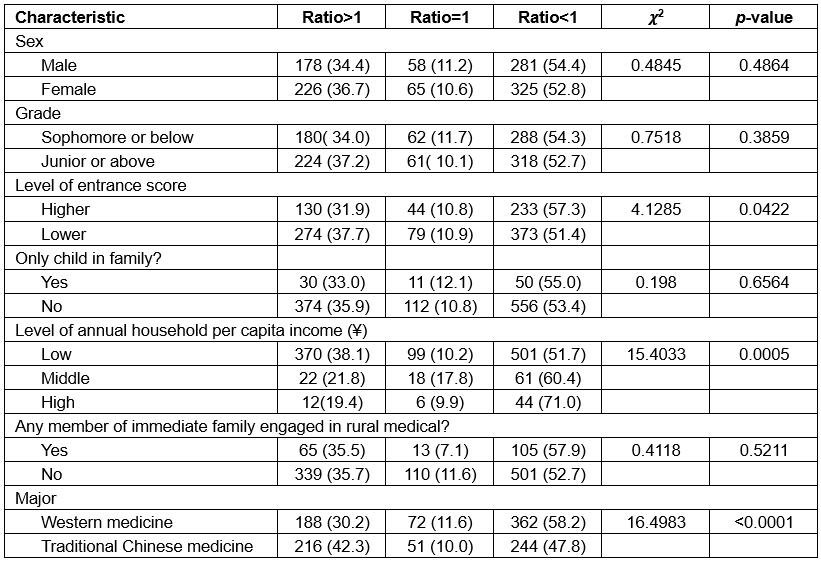

The proportions of the ratios of the attitude scores based on intrinsic motivation to the attitudes scores based on extrinsic motivation were given values of <1 (47.8–71.0%), >1 (19.4–42.3%) and 1(7.1–17.8%).

The results of single-factor analysis suggested that the undergraduates who had lower entrance scores, low level of family income and majored in TCM likely had a higher relative ratio (>1) compared with those who had higher entrance scores, high level of family income and majored in WM (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 2: Scores for attitudes towards a rural medical career, by background

Table 3: Ratios of attitudes scores based on intrinsic motivation to attitudes scores based on extrinsic motivation

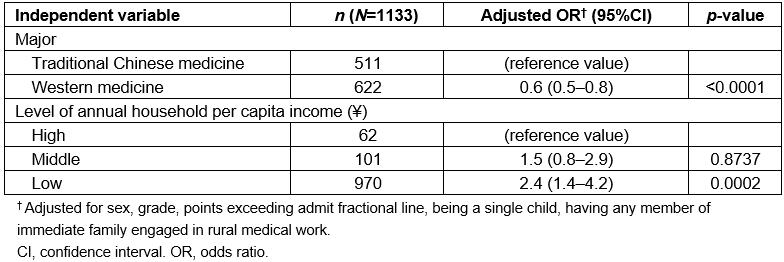

Factors associated with preference of undergraduates’ independent decisions to work in rural areas

After adjusting for demographics, course majors, family backgrounds and the level of entrance scores on the preference of undergraduates’ independent decisions, the resultsof ordinal logistic stepwise regression analysis showed that being an undergraduate of WM was inversely associated with the relative ratios of >1, 1 and <1 (odds ratio (OR) 0.625, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.497–0.785), compared with those who majored in TCM.Compared with the high level of family income, the low level of family income was positively associated with these relative ratios (OR 2.424, 95%CI 1.385–4.243; Table 4).

Table 4: Multi-factor ordinal logistic stepwise regression: factors associated with ratios of attitudes scores

Discussion

Characteristics of selective admission policy in Gansu

The global shortage of well-trained health workers is almost always greater in rural and remote areas, and more acute in developing countries17,18. It is a core obstacle to fundamental health and restricts the development of developing countries19. Shortage of health workforce as a key health risk factor may further exacerbate regional health inequalities between urban and rural areas as well as between developed and developing regions in China6,20,21. It is crucial to train more practitioners for the expansion of basic healthcare coverage and improve grassroots medical services for overall development of China, especially western China.

In China, hospital levels are divided into ministerial level, provincial level, municipal level and county level. Hospitals above the county level and community service stations of cities (containing community health service centres, equivalent to township hospitals) are almost always located in urban areas. County hospitals and hospitals below the county level for the primary medical institutions, such as the township-level hospitals and village health room, are located in rural areas.In rural areas in China, people are served by a three-tier network of health care facilities: county general hospitals and clinics, township hospitals and clinics, and village clinics. In 2016, there were 3.191 million certified doctors in China, of which 0.455 million were in rural areas, accounting for 14.3% of that population22. China’s rural population accounted for 42.65% of the total population on the Chinese mainland23.

Since 2010, the government has introduced a selective admission policy to recruit rural students for 5-year western medicine and traditional Chinese medicine education in order to improve the rural township medical services system of western China24. It was intended that these students could meet the need for rural general practitioners in township hospitals and clinics after receiving free undergraduate education.

The selective admission policy in Gansu province is a combination25-29 of financial interventions as the main strategy (providing undergraduate tuition and fees/bursaries/scholarships), educational interventions (providing postgraduate standardised training for rural medicine) and regulatory interventions (eg compulsory rural service, compensation if a contract is not met).This article describes study participant responses to the ongoing healthcare reform efforts to recruit rural medical workforce by the selective admission policy for undergraduate entry medical students, reflecting attitudes towards rural careers in Gansu province.

Factors influencing rural career choice among medical students under selective admission policy in Gansu

It was observed that intentions to pursue a rural medical career among the medical students covered by the selective admission policy were still not definite, and factors affecting career choice were complex30,31. There was considerable participant uncertainty for each statement related to rural medical career choice. The distribution of the uncertain proportion suggested the lower self-efficacy32 among students, which affects not only the intention to choose a goal, but also the motivation to persevere towards it30. Undergraduates are at the preliminary stage of career choice and career orientation; they lack work experience, so various decision-making difficulties are to be expected.

In fact, although vocational interest is one of the primary factors affecting career choices, access to higher education is the most attractive factor for rural students because of poor education resources in Gansu province. According to general attitudes towards rural career in this study, these students paid more attention to personal benefits, but could not face the difference between higher self-expectation and reality33. Although economic considerations are reasonable, comprehensive and rational thinking is necessary for the students when they apply for the policy.

Socioeconomic and cultural conditions have always affected the values of career choice. The success of a policy on recruitment of medical professionals in underserved areas ultimately depends upon the provision of a rewarding and fulfilling personal and professional environment34. In developed countries, health workers may live in those rural areas that have urban convenience, social resources and unique leisure opportunities. However, Gansu province has a much wider gap between rural and urban areas; rural people live with fewer public resources and greater isolation34. Medical workers in these rural areas work with substandard medical equipment and facilities, inadequate financial remuneration and in a poor living environment. In developed regions, rural medical workers have opportunities to deal with a variety of cases within a relatively good health service system. Thus, more depth and breadth exists in their practice, which is helpful to obtain professional experience and achievement35. However, in Gansu province, most rural patients go to urban hospitals for treatment because of the poor rural health service system. As a result, medical workers have no opportunity to practise and to expand their skills.

In traditional Chinese culture, medical workers of large city hospitals, especially those who undertake specialties, are considered to be the ‘real’ medical professionals, while general practitioners in township hospitals, who provide a broad range of diagnostic, therapeutic, preventive and health maintenance services, are not. As a result, urban medical workers are given more respects and work rewards. The long-term inadequate opportunities for professional growth and uncertain social status contribute to the medical students’ lack of confidence in choosing rural employment, which poses a threat to the effectiveness of the policy.

Improvement of education strategy needed

This study observed that participants’ enthusiasm to work in rural areas is limited and that extrinsic determinants play a more important role in their rural career choice than intrinsic determinants. Possible reasons are that most students had no clear understanding of the policy or self-awareness relating to career choice when they commenced college entrance applications. Clearly, extensive education about the selective admission policy is necessary.

Therefore, advance understanding of the characteristics of candidates for rural medical work is necessary35-38. Further research about career choice motivation among students needs to be done during the policy implementation in Gansu province32.

According to the literature, professional development and ongoing training are important factors influencing recruiting and retention of health professionals in underserved areas39. Therefore, advance understanding of the characteristics of the rural medical workers is necessary as a basis of individual career planning35-38,40. The medical students have to begin with a proper understanding of a rural medical career so that they have good recognition of its professional value, otherwise they are likely to work in rural areas only temporarily, out of obligation. To perform the contract obligations is a fundamental principle of good faith for these applicants, but it does not guarantee the sustainability or success of the policy. What could be done is to increase rural practice exposure through well-planned programs during undergraduate medical education and introduce the further incentive mechanism to general practitioners.

Research about career choice motivation among students is not taken seriously during policy implementation in Gansu province32. As part of school life, students should not only learn cultural knowledge, but also achieve growth of values and self-improvement. Improving psychological development in relation to careers should be helpful to general medical students. Whether the policy can have the effect of increasing medical workforce resource not only depends on the quality of a student’s professional training, but also on the humanistic quality of education41-43. The authors found that dissatisfaction was expressed in relation to not only income, but other aspects of professional life, which suggested that the remedial focus need not be on monetary rewards alone. Therefore, psychological development and humanistic education should be paid more attention as an education intervention for the medical students under the policy.

Educational strategy should not be isolated from the whole social system. Although the issue of compensation has not been solved adequately44,45 in rural areas, along with the advancement of new medical reform there should be substantial development in rural health enterprises in Gansu46,47, which would provide the possibility for general practitioners’ personal career achievements and life ideals. As undertakers of training, higher medical education institutions should provide curricula specifically concentrated on personal and professional achievements and the development of rural health service to the undergraduates48,49. The education strategy combined with the social culture of new public opinion must be encouraged and guided effectively.

Adjustment of selective admission policy for medical students according to regional characteristics

This study found that those who majored in traditional Chinese medicine had more initiative attitudes towards a rural medical career than those who majored in western medicine. A similar situation existed between the undergraduates from low-income families and their counterparts from high-income families. It suggested that prioritizing recruitment for students majoring in traditional Chinese medicine and those in low-income families would result in more stable and sustainable rural career choices.

Traditional Chinese medicine has played a predominant role in the Chinese rural health service system, especially in western China, due to the more popular price of Chinese herbal medicine and service cost, more responsive private care to meet patients’ needs and the absolute predominance in Chinese traditional culture. Gansu province is the birthplace of traditional Chinese medicine, with abundant resources of Chinese herbs, and the corresponding formulas and therapeutic methods were inheritedby people historically50. During the period of the Thirteenth Five-year Plan of China, the government put forward a series of plans to speed up traditional Chinese medicine development46,47. The selective admission policy should take full advantage of the macroscopic policy circumstances of the development of traditional Chinese medicine to provide priority for development and recruitment of rural medical staff.

Moreover, the effect of family financial status on decisions about work location should not be underestimated. Support policies are still needed. For example, medical staff salaries in rural areas should be increased and the whole living and working environment should be improved significantly, which might be an encouragement for those with low family incomes to apply for and remain in rural careers. Surely, comprehensive social development strategy is the fundamental way for regional health equalities, not just the specific financial strategy of the selective admission policy.

Conclusion

The selective admission policy for medical undergraduates with rural origin is the first policy mainly based on a certain financial intervention contributing to reducing the gap of health human resources between rural and urban areas in western China. Rural career choices of medical students under the policy are still not determined and influencing factors are complex in Gansu province. Further strengthening of the educational intervention is necessary, which should emphasise the students’ inner qualities and recognition of professional value as a rural general practitioner. Policy adjustment should prioritise recruitment of students who major in TCM and those in low-income families. The policy should be appropriate to the regional characters of Gansu province; to a large extent its effectiveness depends on the whole social policy system and national development strategy. Overall, support strategies would relieve the candidates’ worries of working and living in rural areas for a long time. Developing a more integrated policy to attract talents to narrow the health workforce gap between urban and rural would be a realistic way.

Strengths and limitations

Information bias in survey responses is always difficult to avoid in self-reported questionnaires. Also, this is a cross-sectional study, which prevents us from making causality inferences. However, the identi%uFB01cation of influencing factors is usually the initial step for the development of an intervention program; in particular, there is an analysis based on the dimensions of internal motivation and external motivation. In addition, unintended factors might exist, potentially confounding the results. Further long-term evaluation should be confirmed. Finally, this is a regional study in China, which has a very diverse mix of social, economic and healthcare systems different from other regions. Perhaps this is the uniqueness of it. Therefore, it is necessary to be cautious in making generalisations to the whole country or to other countries.

Acknowledgements

This study has been co-funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 17LZUJBWZX008), the program of Education Reform Fund of Lanzhou University in 2015 (grant no. 201530) and the program of the Innovation Education Fund of public health in Lanzhou University in 2014 (grant no. 201413). The authors are grateful to the Medical College of Lanzhou University and Gansu University of Chinese Medicine for recruitment of subjects to complete the questionnaire. We thank all the medical students and rural workforce agencies in Gansu province who participated in the survey.