Introduction

During remotely supported prehospital ultrasound (RSPU), an ultrasound operator performs a scan and sends images to a remote expert for interpretation1. This technology aims to broaden access to ultrasound by overcoming the need for experts to perform and interpret scans on site. This concept has been tested in a number of settings, including merchant ships, mountainsides and on the International Space Station2,3. RSPU is currently being investigated in remotely located ambulances in Scotland within the SatCare trial. This trial hypothesises that RSPU may improve triage and prehospital interventions and might expedite the treatment of patients. The aim of this study was to assess perspectives on RSPU amongst acute care providers prior to the start of the SatCare trial.

The SatCare trial involves situating ultrasound devices aboard five emergency ambulances serving remote Scottish Highland communities. Satellite communication with the hospital in Inverness, on the north-east coast of Scotland, will allow images collected by paramedics to be viewed by emergency physicians. Patients will be randomised to receive remotely supported ultrasound or standard care. It is hoped that this trial will demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of RSPU in rural Scotland. It aims to build on the success of prehospital ECGs in reducing mortality rates following myocardial infarction4, as well as the success of trials of doctor-administered point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in the prehospital environment5,6. It also seeks to explore the potential for telemedicine to provide alternative solutions to the challenges of healthcare provision in remote and rural areas7,8.

This is an original application of telesonography, therefore qualitative or quantitative literature are limited. This is in part due to the novelty of the technology but it also reflects the relative paucity of prehospital research9-11. As a result it is recognised that greater participation in research will be essential to improve patient outcomes12,13. To achieve this there must be collaboration between researchers and practitioners, including paramedics and emergency/prehospital physicians14. However, prehospital and emergency research poses unique challenges. Although physicians often have substantial exposure to hospital-based research during their undergraduate and postgraduate training15, clinicians in emergency departments often lack knowledge of the prehospital environment16, have insufficient time for research and may find aspects of communication and implementation of prehospital research difficult11,17-19. Furthermore, participation in research is less widespread in paramedic services11,20,21. Previous studies have found that paramedics describe multiple barriers to research participation including concern for patient safety, perceived lack of clear benefit, too much paperwork, too little time and an agency culture not receptive to change20,22,23. It has been reported that paramedic concerns over participant consent24,25, training requirements26 and noncompliance with protocols posed significant challenges in several large prehospital trials27-29.

Recent achievements have shown that these problems are not insurmountable30. Opportunities include increasing paramedic motivation to participate in research24,26, increasing acceptance of the need for evidence-based practice and a desire to professionalise the paramedic role23,27,31. It is hoped that exploration of the views of physicians and paramedics can overcome human barriers to research success (such as poor adherence to trial protocols) and technical barriers (such as development of procedures appropriate to the prehospital environment)11,14,32.

The rationale for the use of telesonography in this setting is based on existing research in the classroom and hospital setting. Within the prehospital arena, ultrasound has been found to have improved sensitivity compared to physical examination by paramedic alone33-35. Furthermore, it has been found to be feasible to perform in various locations, quick36, easy to teach in a classroom setting37 and possible to employ during transit38. Also, it can be used concurrently with critical interventions33,39, and can facilitate more rapid patient assessment and disposition40. However, some are concerned that the adverse consequences of ultrasound use in prehospital and emergency medicine have been insufficiently explored and that the total benefit to patients is as yet unclear41,42. Similar controversies exist regarding the use of both in-hospital and prehospital RSPU. Proponents argue that RSPU has been shown to have a similar error rate when compared to in-person examinations by ultrasound experts43,44. However, critics argue that there are risks posed by poor transmission reliability45-47 and poor image quality48,49.

Given the complexity of this intervention and the number of stakeholders involved, it is necessary to gauge the attitudes of trial participants towards RSPU50-52. An exploration of these issues will aid the understanding of the conditions that may contribute to the success or failure of this and similar trials53. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to answer the following questions:

- Do acute care providers understand RSPU and think it is a legitimate addition to their practice?

- Is RSPU likely to be supported by acute care providers if it were introduced?

- What are the potential practical challenges or difficulties involved in RSPU and how might these be anticipated?

Theoretical framework

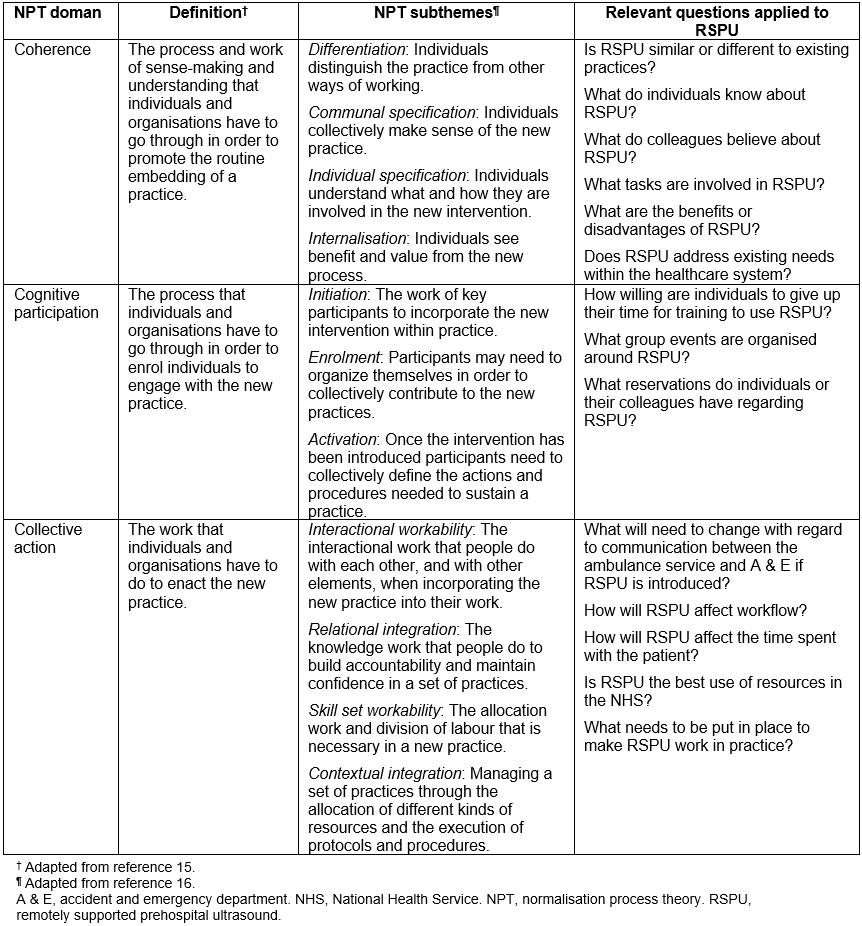

Normalisation process theory (NPT) provides the theoretical framework for this investigation. NPT has been developed as a tool for understanding the ways in which novel practices are integrated into day-to-day work54. It has been used extensively in the qualitative evaluation of healthcare interventions, particularly within the field of telehealth and complex, multidisciplinary interventions55. It was selected for use within this study as it focuses on the legitimacy of the intervention and the work that is done by groups of practitioners to embed a new technology. It also considers the trust required between groups, the role of opinion leaders, and of contextual and organisational factors. Therefore, NPT is well suited to the fields of emergency and prehospital medicine, which depend on successful teamwork, involve a diverse array of practitioners, and are influenced by challenging and diverse contextual conditions. NPT describes four key questions that should be considered; three of these are relevant to this study. The constructs and their translation into this setting are described in Table 156,57.

The fourth domain of NPT, which addresses how an issue might arise and be countered (reflexive appraisal), will not be considered given that the intervention has not yet been implemented. The NPT structure was used throughout this study including during the development of the interview schedule and as a framework for analysis.

Table 1: Summary of the concepts of normalisation process theory and application to the present study.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between February and March 2017 using semi-structured interviews with paramedics and consultant physicians involved in the SatCare trial. The interview schedule was developed through use of the NPT constructs, and thought was also given to relevant concerns regarding the effect of RSPU on workflow, diagnosis, treatment, relationships and training. Pilot interviews were conducted with two paramedics and one physician not involved in the SatCare study. This facilitated refinement of the phrasing and sequence of questions.

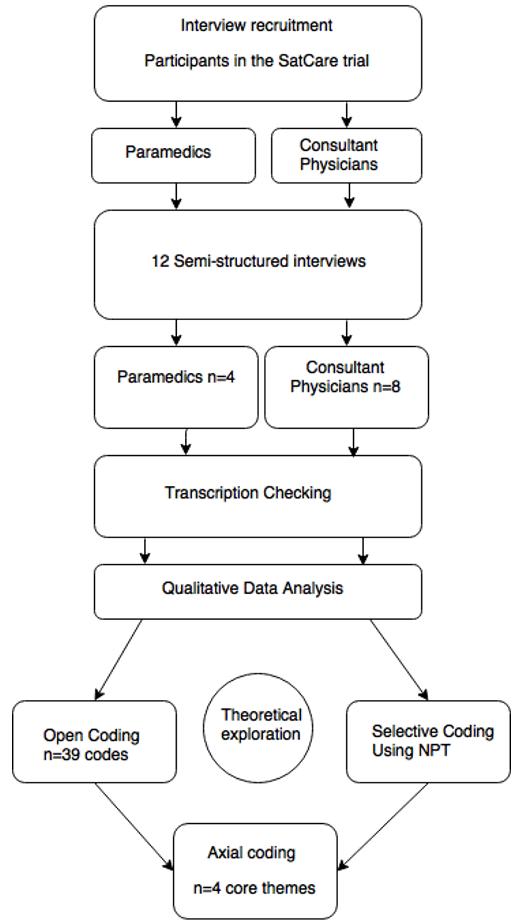

Purposive sampling was used to identify participants to take part in interviews; participants were recruited until theoretical saturation was reached. Interviews occurred either face-to-face or over the telephone, and were audio-recorded. Data were processed immediately after collection and were managed using the NPT framework combining both case- and theme-based approaches. The data were externally transcribed and transcriptions checked by one of the authors (GMF). The data were coded by GMF with discussion and supervision from two other authors (LE and PW). Coding was carried out through systematic reading of the transcripts, supplemented by a review of the recorded audio files and field notes taken during the original interview. Open coding took place initially, then discussions between investigators facilitated the development of a coding frame. This allowed disagreements concerning codes to be explored and resolved. Following this initial stage, hierarchical axial coding was conducted, using NPT in the management and analysis of codes. Constant comparison was used to ensure consistency of coding throughout the process and to refine the themes uncovered. Memos were used to explore emerging themes, facilitate comparison and to support the development of the final analysis. NVivo software was used in the processing and analysis stage. A flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the study process.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the study process.

Ethics approval

This study was granted ethics approval by the University of Aberdeen’s College of Life Sciences and Medicine Ethics Review Board (CERB/2016/12/1408), and NHS Highland research management approval was obtained.

Results

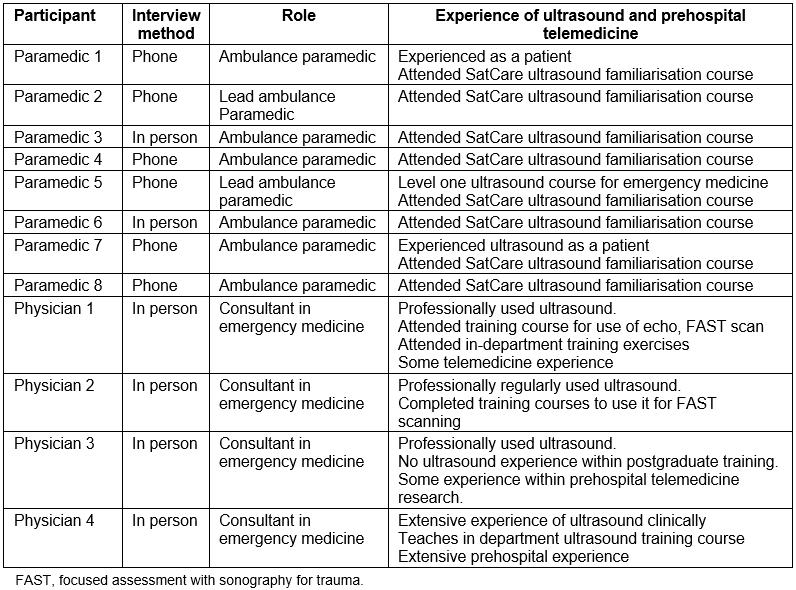

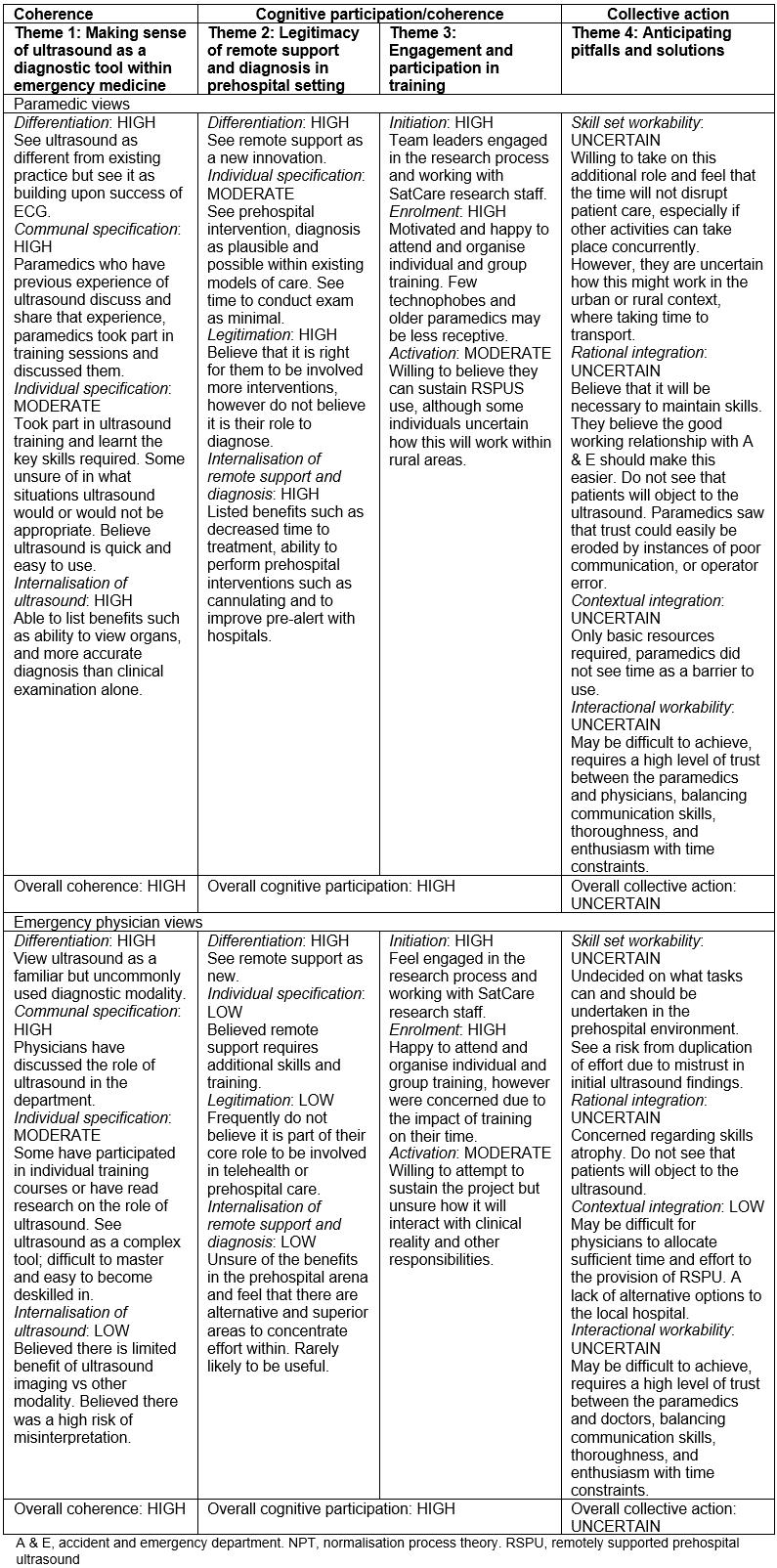

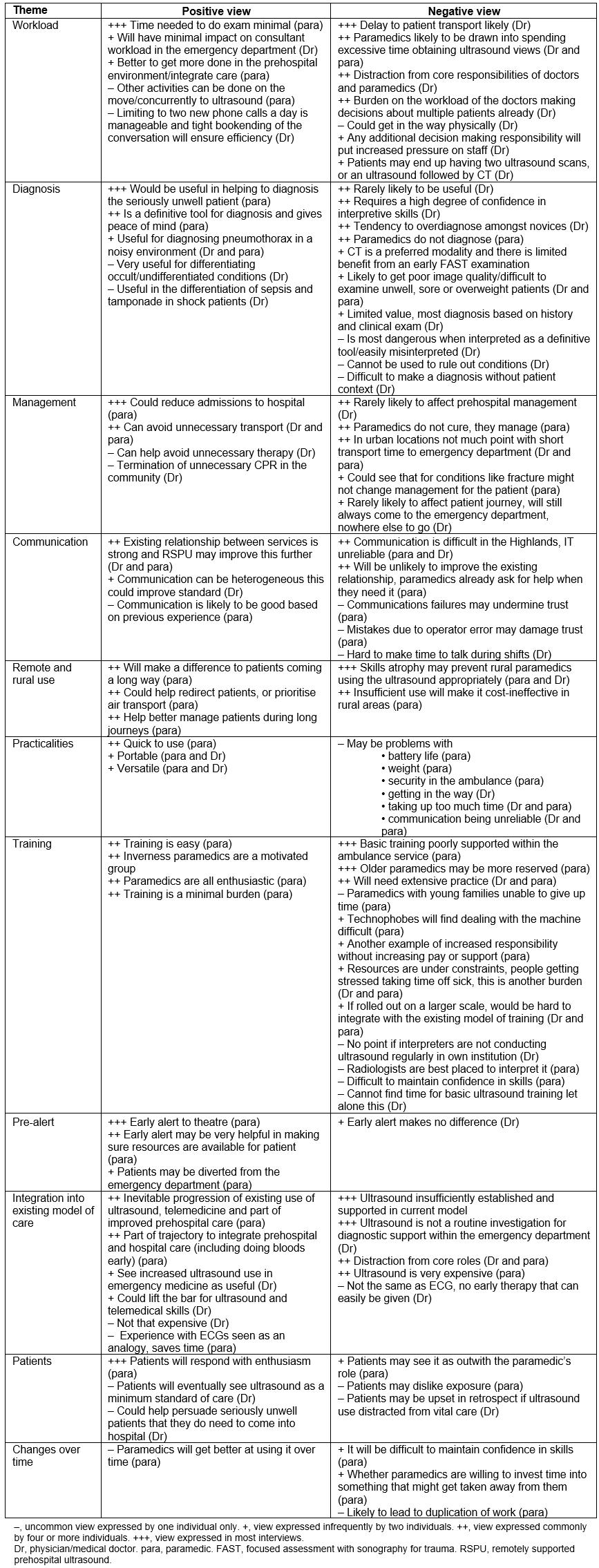

Twelve respondents participated, four of whom were consultant emergency physicians and eight were paramedics. All paramedics had participated in a short familiarisation course involving didactic teaching by an emergency physician and a session of hands-on practice with the ultrasound machines. A summary of participant characteristics is shown in Table 2. The key themes identified and mapped within the NPT framework are summarised in Table 3. More details of comments are included in Table 4.

Table 2: Participant characteristics and their experience of ultrasound and prehospital telemedicine.

Table 3: Summary of study findings according to themes identified and concepts from normalisation process theory.

Table 4: Summary of the views of doctors and paramedics concerning remotely supported ultrasound.

Theme 1: Making sense of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool within emergency medicine

In general, paramedics were extremely enthusiastic about the potential of ultrasound and frequently made statements such as ‘Ultrasound is the future. In prehospital care anyway …’ and believed that it ‘is proven technology’. Paramedics’ understanding of ultrasound was based on personal experience as patients, enthusiasm of colleagues who had been part of a previous prehospital ultrasound trial, and the SatCare ultrasound familiarisation course. Following their experiences in this familiarisation course, paramedics saw ultrasound as quick, simple and were ‘quite surprised that it is not really that difficult to use’. They were also impressed at how ultrasound enabled them to visualise structures and felt the technology was a great improvement from just ‘the intuition of a paramedic’. Some remarked that outside the classroom (especially on an obese or sick patient) ultrasound use might be more challenging. Overall, paramedics believed ultrasound was a ‘fantastic piece of kit’ that could give them, at best, ‘definitive answers’ or at least support their clinical evaluation and ‘confirm what I am already thinking’.

It is not a case of a palpating a belly and hoping that nothing has changed, or not being sure. You have got a definitive answer then and I think that is what ultrasound would give us. Peace of mind. (paramedic 5)

The physicians were more reserved and only one used diagnostic ultrasound in routine clinical practice. Most believed that the role for ultrasound in emergency medicine was in a discrete number of clinical scenarios, including the diagnosis of patients with pneumothorax or undifferentiated shock. In this context, they saw increased ultrasound use as able to ‘give us a wider breadth of diagnostic ability’. Moreover, they believed ultrasound to be a complex tool, difficult to master and easy to become deskilled in. They were also concerned regarding the potential for misinterpretation, especially if ultrasound was understood as ‘being overly reassuring or excluding of a condition’. Therefore, most physicians viewed ultrasound as an adjunct, or an ‘extension of the clinical examination’ and were unconvinced of its benefit in most clinical scenarios.

I suppose I am a bit more sceptical than some. That is probably a reflection that it has not been something that has been part of my training so I start from a different position from most other people who have been exposed to that through their training … I suppose generally speaking I am thinking of trauma and CT, whereas I don’t know if ultrasound adds so much to the diagnostic process. (physician 3)

Theme 2: Legitimacy of remote support and diagnosis in the prehospital setting

Many paramedics saw RSPU as useful in increasing the ability of paramedics to triage patients confidently, leave patients with minor problems at home, prioritise patients for air transport or admit directly to a ward. Some paramedics thought that RSPU might enable them to alleviate the burden on busy emergency departments by taking on tasks such as venepuncture and the siting of a cannula. However, many paramedics did not believe that RSPU would significantly alter treatment or patient outcomes in a way that could be shown ‘on a piece of paper to show an accountant’ – particularly as some paramedics believed ‘my treatment is managing rather than curing’. Instead, paramedics valued RSPU for enabling them to ‘know what was going on’ with their patients and receive advice or support (especially during long journeys within the Highlands). Paramedics often referenced anecdotes where they had witnessed patients with occult injuries deteriorating unexpectedly and thus viewed an ability to recognise serious pathology as ‘an advancement that is needed’.

On your own in the back of an ambulance with somebody that is not as qualified as you are, but still you are only at paramedic level, it can be a lonely place sometimes. (paramedic 5)

Some paramedics and physicians felt there might be risks associated with increased knowledge, which could overstretch or distract from core roles. Consultants believed the primary role of the ambulance service should remain ‘ABC [first aid] management’ and rapid transport to secondary care. Both groups believed RSPU might result in delays to transport through, as one paramedic described ‘faffing about trying to get a better view’ or by encouraging paramedics to carry out tasks that would be more appropriately carried out in hospital.

I think that the more you train a paramedic to do, the more you increase their skill set, the more they feel they will have to do and there might then be some discrepancies where they are spending time on trying to get an ultrasound when in reality we could probably have had the patient at resus … (paramedic 6)

Although paramedics frequently cited trauma as a good indication for ultrasound, they recognised that in some cases it would be more appropriate to just ‘get to hospital’. In the view of the physicians, early diagnosis might hold limited value in the ‘vast majority’ of patients. They also believed that a change in management would be ‘very rare’, mainly ‘because in a prehospital situation there is often a limited amount that can be done’. Furthermore, most physicians viewed early diagnosis as unhelpful because there were limited alternatives to hospital admission through the emergency department.

I don’t see how the ultrasound interpretation is going to influence the specific management in the field, or certainly in this situation where it is going to influence where the patient might be taken. You might argue otherwise geographically in other places where it might influence that. There is only one place they are going to come; they are going to come to the emergency department of [hospital] because there is nowhere else for them to go. They are not going to go straight to theatre or whatever … (physician 3)

However, another clinician was more optimistic:

I think it will end up turning around that relationship for these patients, such as we are asking the ambulance service to do things that they wouldn’t otherwise be asked to do. And even if that is just to the point of ‘can you sit the patient up, take them off oxygen, could you try and site a cannula …’ that is quite a lot of stuff being pushed back into the ambulance by us. (physician 4)

The variation in perception of the potential RSPU amongst physicians in part resulted from unfamiliarity with prehospital medicine (‘I haven’t been on any prehospital courses, let alone worked in a prehospital environment’) and a feeling that telehealth was out of the comfort zone of the physicians. The paramedics had a generally optimistic view of what they could achieve, expressing a belief that their ‘job has evolved’ and would include more remote telemetry and telehealth in the future.

Theme 3: Engagement and participation in training

Collectively, the paramedics and physicians had great confidence in the engagement of the paramedic team, describing the ambulance service as having ‘good, really motivated staff’ with a number of team leaders looking to drive the process forward. When asked who might be sceptical of the intervention, most paramedics referred to paramedics who were trained in the ‘scoop and run’ culture, were ‘technophobes’ or had less free time for training. Furthermore, paramedics felt that if this system were to become more widely adopted, this increase in responsibility should be recognised with investment in training, higher salaries and the development of a more supportive relationship with management. However, most paramedics described enthusiasm about learning new skills within the trial.

The majority of crews really crave further training and further knowledge, it is just a bit inconvenient that you have to do it on your own time. (paramedic 7)

Physicians were willing to engage with training opportunities and had already attended and enjoyed ultrasound courses in their own time. Nonetheless, they saw the burden of the training on rota commitments as significant and a concern ‘because all extra training is an issue’, especially as they believed existing ultrasound training in postgraduate medicine was insufficiently supported and substantial training commitment would be needed for confidence in interpreting RSPU images.

Theme 4: Anticipating pitfalls and identifying solutions

Paramedics talked about potential teething problems; for example, some thought that the novelty of RSPU might lead to overuse early in the trial. Participants thought most patients would be willing to be scanned. However, they considered that there may be some distrust of paramedics amongst the older generation, or anger in retrospect if harm was thought to have resulted from a change to standard care. Paramedics often noted that RSPU might provoke a similar reaction to the that for the introduction of prehospital ECG, when ‘people were very sceptical about what paramedics could do’. Both physicians and paramedics believed that such mistrust might result in duplication of effort and delays due to the performance of repeat scans. Equally, some paramedics saw that trust could easily be eroded by instances of poor communication with the emergency department.

I think it needs the buy in from both sides. I think we have got a good working relationship with A&E [accident and emergency department] but I think the scepticism will come the first time it is used, and the person that is answering the phone or the radio, or whatever device it is going to be, has to go looking for somebody or isn’t overly interested because they haven’t been trained in it. That is the fall down … It will only take a few fall downs before people start getting a bit sceptical. (paramedic 5)

Physicians also described difficulties in achieving a level of trust and skill where ‘the paramedics feel competent to do the scan and then for us, do we feel competent to interpret it’ especially as there is a tendency for ‘new users to over-report’. Furthermore, there was concern that ‘patient context and removal of their care context can influence the decision making’ and increase the risk of errors, especially where interpreter experience, environmental and patient factors could preclude obtaining clinically useful images. Furthermore, both physicians and paramedics were concerned that while in an urban setting a high volume of patients would facilitate frequent use, there may be limited utility of RSPU as patients would be at the hospital in ‘30 minutes anyway’. Conversely, they believed that prehospital intervention could be more significant in a rural setting with long journey times, but due to the low caseload RSPU may be cost-ineffective with a high risk of skills atrophy.

The ironic situation that I think they are in is I think the ultrasound will probably have the greatest impact in the most remote, rural places but they will probably struggle to get enough jobs to justify it … one of the big problems we have is the paramedics getting deskilled in these areas … (paramedic 6)

Participants agreed that there was ‘a very good relationship at the moment with A&E and the ambulance service’. However, there were mixed views about how RSPU might be contextualised in the existing model of practice: some believed the existing practice of remote ECG telemetry and the extensive use of ambulance pre-alert made ultrasound a logical progression; others believed there was too little experience of ultrasound, prehospital care and telehealth to support the introduction of RSPU. Furthermore, some physicians felt increasingly under pressure at work and saw RSPU as ‘another workload’ that must compete with existing demands on their time and cognitive resources.

… often you are in the face of making multiple decisions about different patients at one time. So to add another potential decision making process or something else you are going to be involved in without it actually generating potentially, in my opinion, much of a benefit could be a significant disadvantage. (physician 3)

Both parties were conscious that RSPU was ‘maybe not the best use of the money’ and recognised that its application was complicated by the need for ‘multi-service, multi-disciplinary engagement’ and were unsure whether nominal support would be translated into ‘clinical commitment’ by management should the trial be successful. Some saw that there was friction between research ‘enthusiasts’ and the clinical ‘pragmatists’, who are more focused on ‘the realities on the ground’. Some believed that there was potential for enthusiasm for the technology to ‘overtake science’ and evidence of benefit.

Maybe we need a bit of technology enthusiasm just to keep us all going. Just to change the flavour of the day, the week, the month, maybe that is a good thing. It becomes an increasingly difficult pill to swallow when you see increasing problems with funding core business, core service, core design activities to say we have got to get patients from one end to the other end of the hospital, efficiently and safely and hopefully as many as possible alive or comfortably dead. (physician 2)

Despite their concerns, both paramedics and physicians felt that there were opportunities to address problems within the trial. For example, physicians were particularly glad of the early trial set-up discussions, which had clarified that if the emergency department was busy then physicians could refuse to interpret images and ask paramedics to limit the conversation to a short pre-alert. There was a need to site the ultrasound viewing area in a convenient location within the emergency department, and to address basic practical challenges in ambulances, such as communication blackspots, difficulty operating the probe with scalloped stretchers, freezing of the batteries and problems with the weight of equipment. Paramedics emphasised the need to maintain the momentum of the learning process; paramedics saw repeated drills and the use of prompt sheets as essential, and many paramedics wanted access to practice on the ultrasound machine in the ambulance station. Although most paramedics felt that training should be kept focused, others wanted a more detailed approach and access to further learning materials such as ultrasound manuals.

Thinking about how ultrasound might be taken forward within prehospital care, some participants suggested ways in which the expense of RSPU could be reduced, for example sharing equipment with general practitioners in rural areas, or limiting ultrasound use to groups of specially trained paramedics. In order to overcome problems with transmission or communication, one paramedic discussed the possibility of having a print-out to hand over to the emergency department should the transmission fail. Both paramedics and physicians were most familiar with the utility of ultrasound for venous access and suggested this as an area for exploration in future trials. While there was optimism and pessimism surrounding many issues within the SatCare trial, participants universally expressed their willingness to engage with the research process.

We don’t jump on all bandwagons with huge enthusiasm but if this has a very definite positive outcome, then it will simply become the responsibility of the organisation to identify how it wants to deliver upon that success. (physician 2)

Discussion

This study aimed to develop an understanding of the potential for RSPU to become normalised within the daily practice of paramedics and doctors working within the SatCare trial. Using the NPT framework it was possible to develop an understanding of staff perceptions of this technology. These results show that while the capacity for normalisation of RSPU amongst paramedics may be strengthened by a strong sense of its value, participating doctors are in general more sceptical of RSPU technology. It is clear that there are substantial risks to the success of this system; a high level of trust between both doctors and paramedics, substantial skill from both parties and a significant amount of effort are required to achieve this type of service. While comparisons to prehospital ECG are useful, RSPU presents distinct challenges that may be difficult to overcome given the increasingly pressured environment into which this technology is being introduced.

There is limited literature with which these findings can be compared as a result a dearth of prehospital research58 and the contingency of these findings upon the precise context and design of the RSPU system involved. Nonetheless, the issues raised by the practitioners included in this study are echoed within related fields. First, physicians had mixed views regarding the use of ultrasound, a modality increasingly incorporated into numerous specialties59,60. Ultrasound is advocated by enthusiasts, who argue that POCUS is versatile, cost-effective, reduces time to diagnosis, and results in no worse mortality than algorithms using CT59,61,62. However, it is seen by others as ‘fraught with scope for diagnostic error’63. In the present study, several physicians expressed concern over the risk of excessive reliance on ultrasound findings. This concern is supported by evidence that overconfidence and insufficient awareness of the limitations of POCUS are significant risk factors for diagnostic error64.

There are widespread disagreements over the role of prehospital care in the UK65. In this study there was some doubt amongst physicians concerning the value of prehospital intervention (the so-called ‘stay and play’ approach) when contrasted with the traditional prioritisation of rapid transport (the so-called ‘scoop and run’ approach)66,67. There is some evidence that prolonged on-scene time is associated with mortality, especially in trauma68,69, and that prehospital intervention does not improve patient outcomes70. This has been contested, as both decreased mortality and no effect on transport times have also been reported71,72. The rapidly evolving professional identity of paramedics is another likely contributor to uncertainty surrounding the role of prehospital medicine. Increased demand on the ambulance service and a rise in non-emergency calls have demanded that modern paramedics have a complex competency range73,74. This has led to the institution of an extended paramedic role, which has in some areas reduced emergency department attendances75,76. Paramedics are enthusiastic over the potential to expand their competencies (although many would also desire more recognition, including financial reward for increased responsibility taken)77. It is unclear which skills might be most appropriate for paramedics to acquire, due to the breadth of the work undertaken. Furthermore, some argue that this expansion may distract from the core purpose of the ambulance service78,79. The desire of paramedics to expand their role is contrasted with the perspective of emergency physicians, who are cautious regarding any increase to existing workload due to issues such as overcrowding, insufficient staffing and lack of flow of patients out of the emergency department80,81.

The physicians in this study felt that there was a conflict between the allocation of financial and cognitive resources to research of unknown benefit in the face of tangible needs to improve patient care. This conflict is exacerbated by the problem of waste in clinical research82, and difficulties in quantifying the value of research compared to the application of existing knowledge within any given field83,84. Therefore, although the technology may be ready for application, it is unclear that the potential benefits of research in this area outweigh the benefit of optimising current practice85,86.

This study has a number of weaknesses. Due to the qualitative nature of this study, it is not appropriate to generalise these findings, and this study will primarily be used to supplement the process analysis of the SatCare trial. Nonetheless, the use of the NPT framework may facilitate understanding of a number of issues raised in this study in a wider context, and it is likely that some themes uncovered in this investigation may be relevant within other settings. This is particularly true of the questions of professional identity, and the value of integration of prehospital and emergency medicine. This study reiterated controversies within this field regarding the future role of ultrasound diagnostics and prehospital medicine within the modern healthcare landscape, issues that merit further investigation. This is an example of how in-depth qualitative exploration may be useful in understanding the research–practice gap, which hinders the application of new health technologies. These findings also illustrate the importance of consultation with staff within trials of complex interventions.

Conclusion

The potential for the normalisation of RPSU within the Highlands is unclear, and views regarding this technology differ substantially between the two professional groups involved. Paramedics are enthusiastic and keen to engage with the RSPU technology, which aligns well with their experience of ECGs as well as their beliefs regarding progression of the paramedic role. However, emergency care physicians expressed a wider spectrum of views. Some physicians were particularly concerned about further extension of their duties in light of existing strains on their time and resources. They were more sceptical that RSPU, and more broadly prehospital intervention, can improve outcomes. Although these differences in opinion pose risks to the successful normalisation of RSPU, both groups also described factors that may aid in its success, including the existence of a strong working relationship between the two groups, and a willingness to engage in the research process. Nonetheless, the success of RSPU will be contingent on numerous factors – patient, operator, contextual and interactional issues – and therefore substantial work and effective communication will be needed to overcome these challenges.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the doctors and paramedics who gave up their time to take part in this study. This includes those who participated in the pilot phase of the interviews, who were instrumental in the formation and refinement of the interview schedule. They also thank the members of the Scottish Ambulance Service (SAS) for their assistance, particularly Dr Jim Ward, Dr David Fitzpatrick and Mr Robbie Farquhar, who provided invaluable advice and guidance in the submission of the proposal to the SAS.