Context and issues

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of health programs in low resource settings can be challenging for many reasons: limited human resource capacity, weak information systems, inadequate financial and human resources, and limited demand for M&E1. However, increasingly rigorous M&E is required by governments and donors to transparently report if programs are implemented as planned and achieving the expected outcomes. This article describes M&E conducted for the Community Mine Continuation Agreement (CMCA) Middle and South Fly Health Program in Papua New Guinea and offers practical solutions as lessons learned from the experiences in this context.

CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program aims and activities

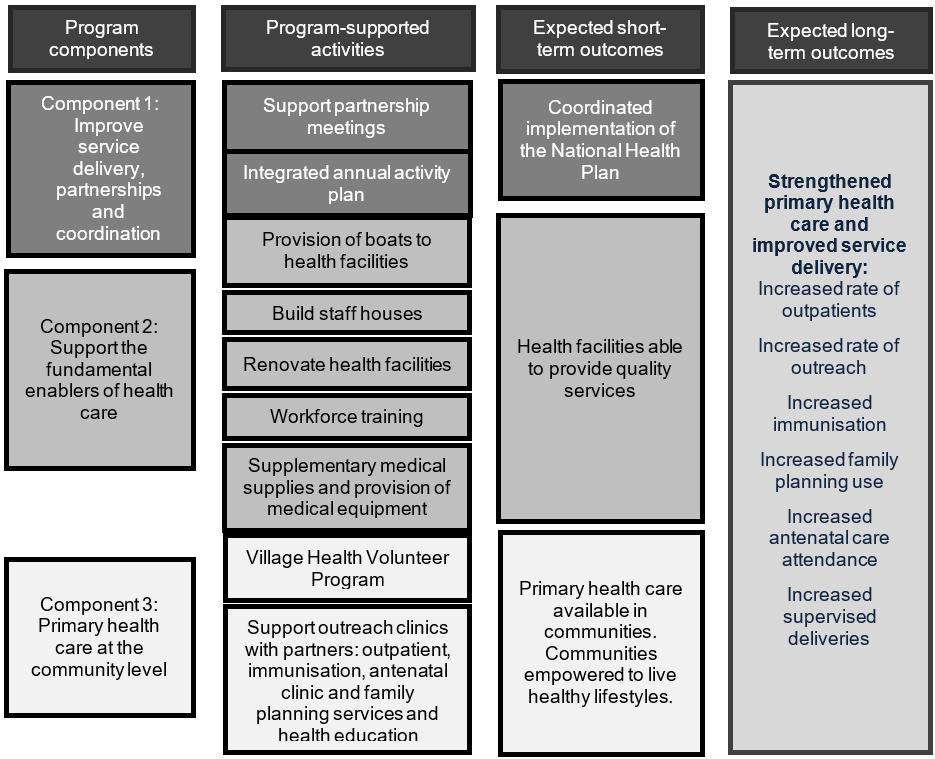

This comprehensive health program aims to improve health service delivery to remote communities in the Western Province of Papua New Guinea2. The program coordinates support through a partnership with existing health service providers, covering all aspects of health service delivery and primary health care (Fig1). Full details of the program are available in an online report of the midline evaluation3.

The program activities are implemented by a multidisciplinary team of about 20 staff, in collaboration with existing health service providers in the program area. The program supports health facilities, servicing 50 000 people. The geography in the program area is challenging, with transport to villages and health facilities often by boat.

Description of the M&E system

The program design was based on a program logic (Fig1). The program design also outlined the following principles for the M&E system: use existing data appropriately; where available, use the national targets or set realistic targets; focus on the needs of users and encourage use of data; and ensure M&E is integrated into implementation and is not a separate activity. Each year, annual activity plans were developed based on the program logic.

The program design also outlined guiding principles for indicator selection: use the minimum number of indicators to track performance, as each additional indicator requires additional resources for collection and analysis; link indicators to inputs, processes, outputs, outcomes and impacts in the program logic and annual activity plan; and, wherever possible, use existing data sources for indicators.

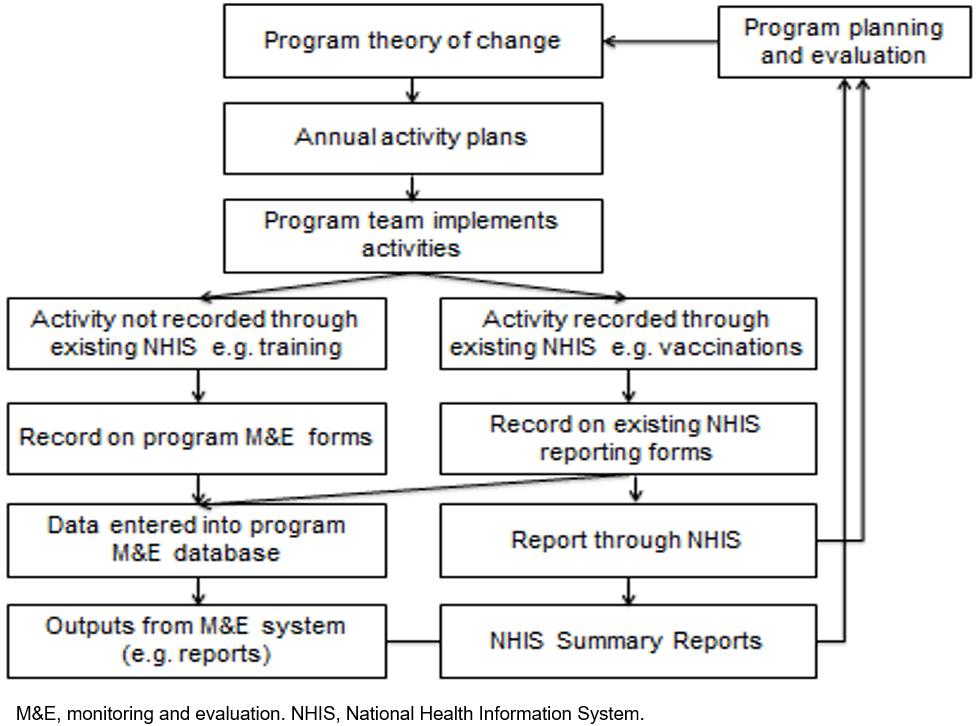

To enable regular progress monitoring and reporting of indicators, an M&E system that incorporated both primary and secondary data was established (Fig2). Secondary data were from the National Health Information System (NHIS), a monthly paper-based information system where aggregate healthcare presentations and healthcare services (eg immunisations, antenatal care) are reported monthly. The NHIS data were used to calculate long-term outcomes (eg immunisation coverage). The program team would use existing NHIS forms to record immunisations given (or any other activity recorded in the NHIS) and provide a copy for the program M&E database and for reporting through the existing NHIS processes. This enabled a direct attribution analysis of the program to the overall indicators (eg immunisation coverage) in the program area. Where no data collection for other program indicators existed, program-specific M&E forms were developed based on the annual activity plan. These M&E forms were filled in by designated staff on a monthly basis (eg the infrastructure officer reported on all infrastructure related activities in the annual activity plan) and entered them into the M&E database. The data from the M&E system were used for monthly progress reporting, annual activity planning and periodic evaluation.

Figure 1: Simplified program logic for the CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program.

Figure 1: Simplified program logic for the CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program.

Figure 2: CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program M&E system.

Figure 2: CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program M&E system.

Lessons learned

1. M&E should be integrated into every aspect of the program

While it is best practice to incorporate an M&E plan into the program design, these plans need to be sufficiently detailed and feasible to enable M&E to commence with program commencement. However, it is not unusual that M&E plans take substantial time to finalise while program implementation has already started4. Furthermore, M&E is often seen as the responsibility of the M&E officer or team, and not of the entire program team.

For the program, a detailed M&E plan was developed in the program design and was integrated across all program operations. The M&E plan included a program logic, an M&E framework (detailing indicators and their link to the program logic, source of data and frequency of reporting) and a reporting framework. There was regular monitoring of program progress and a baseline, midline and endline evaluation. M&E was funded in the budget with specific personnel, a part-time M&E manager, a part-time data manager and a full-time health information officer. A lesson from the program that enhances M&E best practice knowledge is that M&E specific activities, such as monitoring, were integrated into each team member’s terms of reference. This ensured that M&E was integrated into daily activities and annual performance reviews. Overall, this integration of M&E resulted in adequate resourcing of M&E activities, M&E was initiated at the same time as the program commencement and M&E was not viewed as an activity separate to a staff member’s duties but rather a core responsibility from management to field staff.

2. Existing health information data need strengthening

Using secondary data from existing information systems is most cost-effective for M&E. However, health information systems in low resource settings may have issues with timeliness, completeness and accuracy. In Papua New Guinea there is an acknowledgement these issues exist with the NHIS5. Health information systems are one of the six building blocks of health systems as outlined by WHO, forming a critical function in ensuring ‘the production, analysis, dissemination and use of reliable and timely information on health determinants, health system performance and health status’6. As with all the health system building blocks, health information systems are not standalone systems and the ability to generate complete and accurate data has ramifications for all the building blocks7. Programs that aim to support or strengthen one or more building blocks of the health system should also invest in strengthening the health information system, although in practice this does not always occur8.

An element of support for strengthening the health information system in Western Province was integrated into the program design, as part of the work of a health information officer. This officer worked with their government counterpart in the Provincial Health Office, to improve timeliness, completeness and accuracy of the NHIS. This support led to an improvement in both the completeness and quality of the data (completeness increased from 91% in 2012 to 99% in 2015). Furthermore, the review of the NHIS data led to the detection of substantial under-reporting, which was subsequently corrected.

3. Primary data collection should be linked with existing program activities

While using existing data is preferred, health information systems in developing countries do not always collect the required information for program M&E. However, travel to program sites, often in remote locations, for primary data collection adds enormous costs for transport and personnel time. In low resource settings, travel costs can use up scarce funds that would be better used for implementation of activities. The program staff regularly travelled to program sites to implement activities. This provided an opportunity to incorporate program implementation with primary data collection, thereby reducing costs.

The program was launched with an outreach clinic provided to every village in the program area. This was a huge logistical undertaking, given the remote location of many villages. It was, however, a prime opportunity for primary data collection for baseline evaluation. The program outreach clinic team were trained in data collection and were able to carry out health facility assessments, interviews with health workers and focus group discussions with community members, along with their outreach clinics. Baseline data collected by the outreach clinic team were extremely valuable in informing specific activities for the first annual activity plan. Additionally, involvement of the program team in the baseline built their capacity for M&E, and provided them with a deeper understanding of the health services and community expectations.

4. Regular monitoring and feedback are vital for early identification of issues

Process monitoring is the foundation of M&E. Process monitoring enables evaluators to distinguish between a failure in program design or a failure in implementation9. If what has been done is not sufficiently recorded, it is very difficult to evaluate outcomes and impact of programs. For example, poor outcomes may be attributed to the program when implementation was actually insufficient. Furthermore, for transparency, it is important to communicate to donors and beneficiaries about what the program has done.

Process monitoring was integrated into all program staff reporting requirements, which were linked to the annual activity plan. Each month, progress of the annual activity plan was discussed with the team, identifying where activities were on track or if there were delays. This was critical in terms of timely implementation. When delayed activities were identified in these monthly meetings, the team discussed what could be done to overcome the delay. Often this led to allocation of additional resources and closer monitoring to ensure the activity was completed. Changes to activities were documented during these discussions. The documentation resulting from these discussions was used to inform the client and stakeholders about status of program activities and the issues surrounding delayed activities.

5. The program team must be involved in evaluation

The program team were actively involved not only in monitoring, but also evaluation data collection for the program. Periodic evaluations serve to assess whether the longer term outcomes and impacts from the program were being achieved and informed alterations to implementation.

Evaluations can be conducted by either the organisation implementing the program (internal evaluators) or an external organisation or consultants (external evaluators). In a review of case studies of influential evaluations of development programs the use of external consultants was seen as being more independent, with the ability to explore sensitive political issues10. On the other hand, involving an internal evaluator may provide better access to data and key stakeholders, and opportunities for fostering program ownership and learning through team involvement10,11. This was certainly the case for the program baseline evaluation, where the team’s involvement in focus group discussions with communities, health worker interviews and health facility assessments allowed them to gain a deep insight into the issues for planning and implementing program activities (lesson 3). A third approach is a joint evaluation with internal and external evaluators as a way of ensuring independence and contextual knowledge10.

For the midline evaluation of the program, it was no longer appropriate for the program outreach team members to conduct data collection, given their now established relationship with health workers and community members and their role in program implementation. A joint evaluation approach was used with a combination of independent evaluators and the program M&E team, who did not have contact with the health workers or communities.

The role of the independent evaluators was specifically to seek the perspectives of health workers, communities and program partners on changes since program commencement, and on future directions. The program M&E team designed the overall midline evaluation methodology and data collection tools, based on the evaluation questions developed through a meeting with program stakeholders. Independent evaluators conducted key informant interviews and focus group discussions with program team members, program partners, health workers and community members. The M&E team collated and analysed quantitative data from the NHIS. The results from the qualitative and quantitative data were synthesised into a report by both the program M&E team and independent evaluators. This combination of internal and external evaluators provided advantages of in-depth knowledge and context of the program from the program M&E team, and the independent evaluators ensured evaluation participants felt comfortable raising concerns about the program and contributed to the transparency of the evaluation findings.

6. M&E data should be communicated through multiple mediums

The results of the program M&E needed to be communicated to various audiences. The team communicated results in multiple formats: monthly reports to the program team, which served to inform and improve program implementation in real time; quarterly reports to the donor and program partners; quarterly feedback posters and information sessions via the outreach clinic team to beneficiaries, the communities and health workers; and the program website for the wider public.

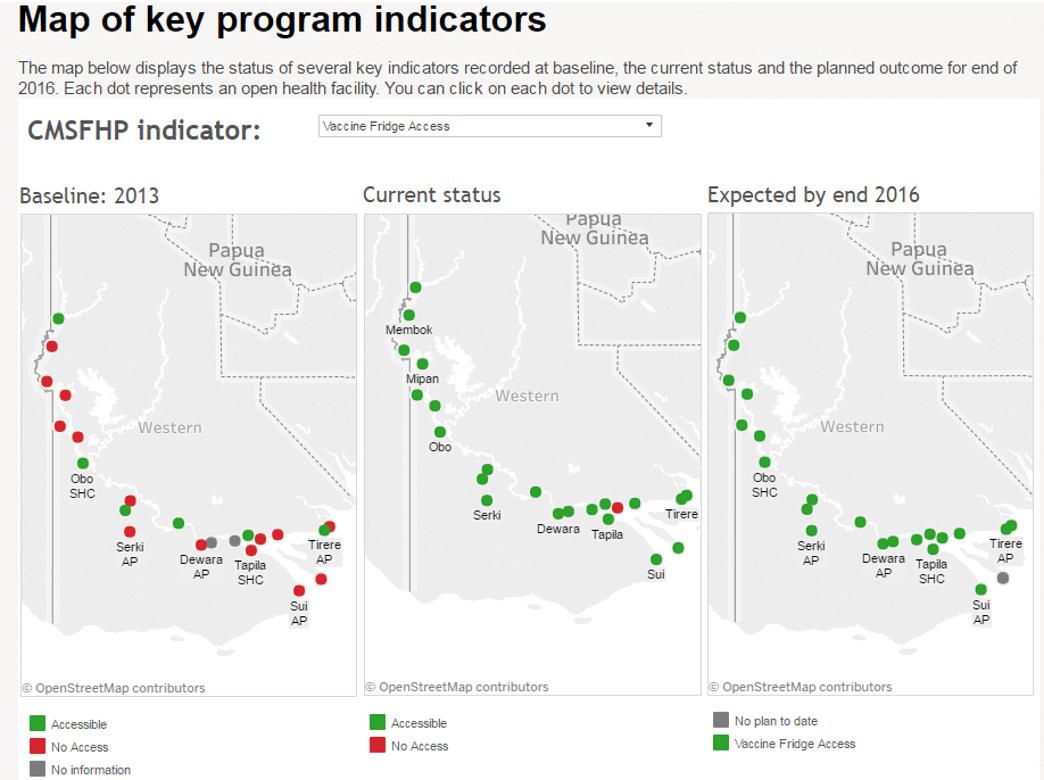

A key component of the program was equitable distribution of program benefits to the health facilities and communities, which was difficult to present in standard reporting templates (eg tables/graphs). Demonstrating this distribution was achieved through mapping program activities by village and health facilities. Data visualisation software Tableau v2018.1.2 (Tableau Software; https://www.tableau.com) was used for maps, which were embedded in the program website. These maps were interactive, allowing users to map different indicators and compare results from baseline and current status. Furthermore, this ensured that stakeholders could access non-confidential program data without having to request data from the program M&E team or wait for routine reports (Fig3).

Prior to the program, data on the health facilities were neither available to health service providers in this level of detail nor regularly updated prior to the program. The program sought to increase demand for data for decision-making through the M&E system, strengthening the NHIS, and regular presentation of data analyses at the program partnership meetings. However, use of data by program partners for decision-making, for example annual activity planning, remains limited. Enhancing the utility of information products generated from the M&E system, through seeking feedback from users, may improve data use for decision-making12.

Figure 3: Example of data from the CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program M&E system displayed on the program website13.

Figure 3: Example of data from the CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program M&E system displayed on the program website13.

Conclusion

This article has outlined lessons from M&E for the CMCA Middle and South Fly Health Program in Papua New Guinea. Integrating M&E into all aspects of the program from program design to implementation assisted in having a solid plan for M&E, an adequate budget, appropriate human resources and buy-in from the entire team. Furthermore, the program team can contribute to primary data collection while travelling to sites for M&E and improve contextualisation of M&E through participating in joint evaluations with independent evaluators. In low resource settings, contributing to strengthening of the existing health information systems, from which the data are often used for M&E indicators, is both beneficial for program M&E and for the health information systems. Regular monitoring and feedback to the program team and discussions of M&E data assisted in identifying issues and improved implementation. Lastly, results from the M&E system were reported in multiple formats, including using maps, to stakeholders. These lessons may be applicable to health programs in other low resource settings.