Introduction

Becoming a mother can be a dangerous proposition in Papua New Guinea (PNG), where maternal mortality ratio may be as high as 733 per 100 000 births1, one of the highest globally2. The Global Burden of Disease Study shows only a 1% reduction in maternal years of life lost between 1990 and 2010, a figure that emphasises the risk to PNG women of childbearing3. Overall risks are exacerbated by more than half of women giving birth without a skilled birth attendant, coming to birth at either ends of their reproductive life (being either too young or too old), and/or giving birth more than five times4.

PNG’s challenging landscape, rugged rural roads and remote community settings make health services difficult to reach, especially for pregnant women, and are often ill-equipped and under-staffed. Only 37% of mothers access skilled birth attendants5 in health facilities. An overall lack of health workers5 with varying levels of professional education and severe lack of continuing professional development4,6 contribute to a workforce that is frequently ill-equipped to manage supervised births.

Improving the outcomes for mothers and newborn babies has become a moral and economic imperative for the PNG government and its international partners5,7. In 2009, a Ministerial Taskforce on Maternal Health made a series of recommendations to address some of the major factors contributing to the problem. These included an urgent need for reproductive health in-service training for health workers, particularly in the areas of family planning, essential obstetric care and emergency obstetric care. The Ministerial Taskforce also asserted that ‘major government, private sector and development partner investments be secured to achieve the ambitious but necessary targets required to turn around the current status of Maternal Health in PNG’3.

‘Shared value’ and PPPs in PNG

International companies profiting from PNG’s resources boom are an obvious source of funding for health projects and other development initiatives. Health service partnerships also provide an opportunity for mining and resource companies to create ‘shared value’, through which businesses can deliver sustainable social impact in developing countries while achieving commercial returns. These partnerships also contribute to the quality of health care available to their workforce and the communities in which they work. Investment in health, particularly in the health of vulnerable women and children, fosters goodwill towards the company by the community, enhancing their social licence to operate8. The Public Private Partnership policy 20089 and new Public Private Partnership Act 2014 guide the setup of PPPs in PNG. However, these formal documents concentrate on partnerships for infrastructure rather than service delivery and development goals, which is the focus of the PPP described herein.

In 2013, the Mining Health Initiative submitted a review of lessons learned in PNG mining health programs to the Australian Government. It identified seven mines with associated health PPPs and conducted cases studies of the Ok Tedi Mine in Western Province and the Lihir Gold Mine in New Ireland Province. Overall, the Mining Health Initiative concluded that despite a number of issues and challenges (especially surrounding stakeholder coordination), health programs engaging the private sector in PNG are having a positive impact10.

Numerous case studies of PPPs for delivery of health services have documented success of the model as well as its challenges. PPP interventions in the area of tuberculosis testing, treatment and care have been demonstrated in Nepal11, Myanmar12, Kenya13, Nigeria14 and Pakistan15, and have shown an increase in tuberculosis detection and successful rates of treatment. These improvements have been attributed to private sector involvement. Malaria programs have also benefited from PPPs, especially for the distribution of insecticide treated nets16.

In 2013, Torchia, Calabrò and Morner17 conducted a systematic review of 46 articles on health sector PPPs published in peer-reviewed journals between 1990 and 2011. Results of the review highlight six main areas for research: effectiveness, benefits, public interest, country overview and context, efficiency and roles of partners. Findings suggested scholars in the field were yet to agree on the actual effectiveness of PPPs. Further case studies in different country contexts were recommended, particularly in regards to the role and expectations of partners17, which this article aims to address.

Reaching out to the private sector

As a result of needing to improve the quality of health services, the PNG government has adopted a policy of increasing assistance from the international donor community and the private sector through PPPs18 with continuing professional development a priority19. While there are many PPPs across the globe, there remains no uniform structure, but they are loosely defined as a collaborative relationship between public and private stakeholders for the achievement of a common goal20,21. They are recognised as bringing expertise on specific topics that assist in meeting population health needs22. A PPP was created in PNG in 2012, between the National Department of Health (NDoH), the Australian Government and the Oil Search Foundation.

Oil Search, the private partner in the PPP, is Papua New Guinea’s largest company, employer and investor. The Oil Search Health Foundation was established as the company’s charitable arm in 2011 (changing its name to Oil Search Foundation in 2015), formalising several decades of its engagement with the health sector in PNG on projects related to malaria and HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment23. The Oil Search Foundation made in-kind payments US$500,000 per year to the PPP discussed in this article24.

The public partners

The public partners are NDoH and the Australian Government, implemented through Australian Aid (now Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)). While NDoH historically is the main public provider of health services in PNG, around half of those services are provided by church organisations25. Recognising its limited capacity, NDoH has decentralised health services through organic law, with NDoH establishing National Health Service Standards19 that define roles at different levels of the health system. Roles of provincial administrations, the local geographical and governmental areas across the country, include responsibility for continuing professional development of health workers19. Development of maternal and child health service providers is a case in point. However, NDoH now acts as a regulatory and policy development organisation, overseeing training rather than conducting it. PNG’s provinces refer to NDoH for endorsement of all training including curriculum and continuing professional development.

The second public partner in the PPP is Australian Aid, now DFAT and formerly AusAID, the Australian Government department responsible for international relations, trade and development assistance programs. Initially AusAID entered the partnership with a commitment of almost A$5 million over 5 years between 2012 and 2016. The resultant PPP of Oil Search Foundation, the NDoH and Australian Aid, described in this article, is the Reproductive Health Training Unit (RHTU).

The Reproductive Health Training Unit

The RHTU is a small travelling training unit based in Port Moresby and consisting of a director/educator, two PNG educators, one expatriate educator (who joined in the third year of the program) and a project leader. It is overseen by a steering committee with members from all three partners and, when relevant, other stakeholders who make decisions for the RHTU. On invitation from a provincial health authority, acting on behalf of their province, the training unit travels with the provincial authorities and educators to conduct training for reproductive health workers in essential obstetric care and emergency obstetric care. The essential obstetric care package encompasses normal antenatal care, normal intrapartum care and normal postnatal care and includes three common emergencies: eclampsia, neonatal resuscitation and atonic post-partum haemorrhage. The emergency obstetric care package is only for reproductive health workers who work in facilities that deliver more than 200 babies annually.

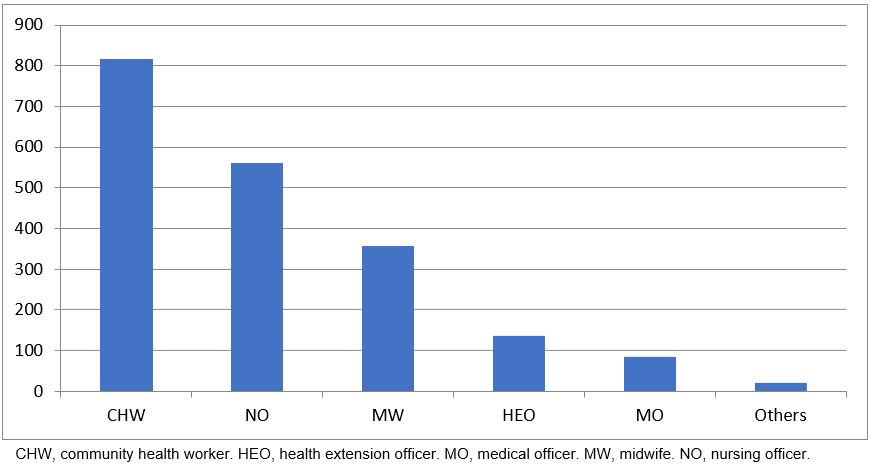

By the end of 2016 the RHTU had trained almost 2000 health workers including community health workers, nursing officers, midwives, health extension officers and medical officers across PNG(Fig1)26. While there are no data linking the training to reduced maternal and newborn deaths (problematic as baseline data is not reliable27), evaluations collected from 1596 course attendees showed 99% would recommend this course to others26. A qualitative evaluation showed course participants were making change and sustaining learning28.

The RHTU is one of the Australian Government’s earliest forays into engaging with the private sector to achieve health development goals in PNG. The aim of this article is to provide a qualitative evaluation to inform future PPPs of the features that have facilitated the implementation of the RHTU and the features that have created barriers.

Figure 1: Cadre of health workers completing a Reproductive Health Training Unit course.

Figure 1: Cadre of health workers completing a Reproductive Health Training Unit course.

Monitoring and evaluation of RHTU activities

The RHTU has a rigorous monitoring and evaluation framework, which guided the focus of RHTU stakeholder interviews and focus groups conducted by this article’s authors between 2013 and 2016. Through this process, changes in perceptions of the PPP were tracked, and strengths and weaknesses identified. The present study resulted from consultations between RHTU partners and other relevant stakeholders to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of a PPP for health development outcomes in the context of PNG. Lessons learned may be applied to the development of similar PPPs.

Method

Study design

A qualitative methodology has been used to come to an understanding of a PPP implemented through the RHTU. Interviews and focus groups were conducted in six provinces: the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Madang, NCD (Port Moresby), Southern Highlands, Morobe and West New Britain.

Two broad research questions underpinned the study:

- From the perspective of the partners and other stakeholders, what features of the PPP enabled the RHTU to be effective?

- What features of the PPP have created barriers to RHTU effectiveness?

Data collection

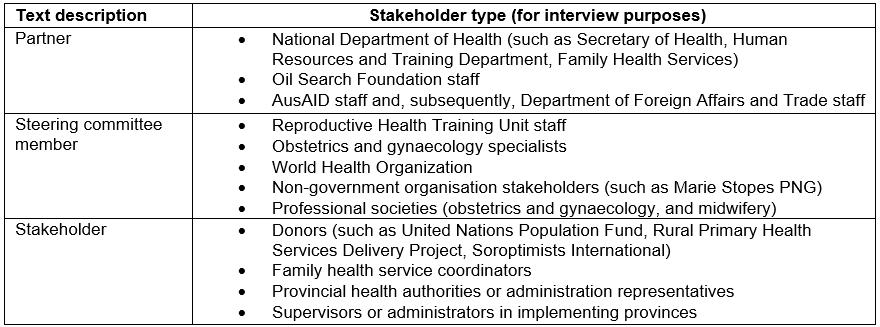

All participants (n=219) interviewed in the process of monitoring the RHTU added to the overall knowledge and observations of this study. However, as not all interview participants were asked about the PPP, a dataset of 85 interviews was selected to be analysed in-depth. Of these, 13 people were interviewed more than once throughout the 3 years to track changes in perception. Quotes that highlight identified themes are attributed to an interview participant by the year the data were collected as well as the organisation they represented (Table 1). ‘Partner’ denotes a representative from NDoH, Oil Search Foundation or DFAT. Other research respondents were steering committee members. Other respondents (such as ‘stakeholder’) are persons who may have been a donor but were neither a partner or steering committee member.

Each interview was recorded and the audio transcribed by a commercial transcription company. Where an interview was conducted in Tok Pisin, it was first translated and then transcribed.

Table 1: Examples of positions of study interviewees

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted on the interview data set and discussions held within the WHO Collaborating Centre of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Development team regarding the interpretation of the content. General patterns and emerging issues from participants’ explanations and descriptions were developed through an inductive thematic analysis29. Insights obtained through field notes, personal observations, historical knowledge, individual interpretations and collective reflexivity were also incorporated into the analysis, to ensure triangulation of data from multiple sources30. The qualitative software NVivo v10 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products) was used to organise interview transcripts and assist coding for specific themes.

Ethics approval, consent and data anonymisation

Ethics approval was received from the Medical Research Advisory Committee at the National Department of Health PNG (#MRAC 14.19) and HREC University of Technology Sydney (#2013000589). Before data collection each interviewee was given an information sheet and asked to sign a consent form. The information sheet was also explained in full, as written English was sometimes difficult for interview participants. No identifiers that would allow tracing of comments to a particular respondent were used in data collection, except for the organisation that respondents represented.

Results

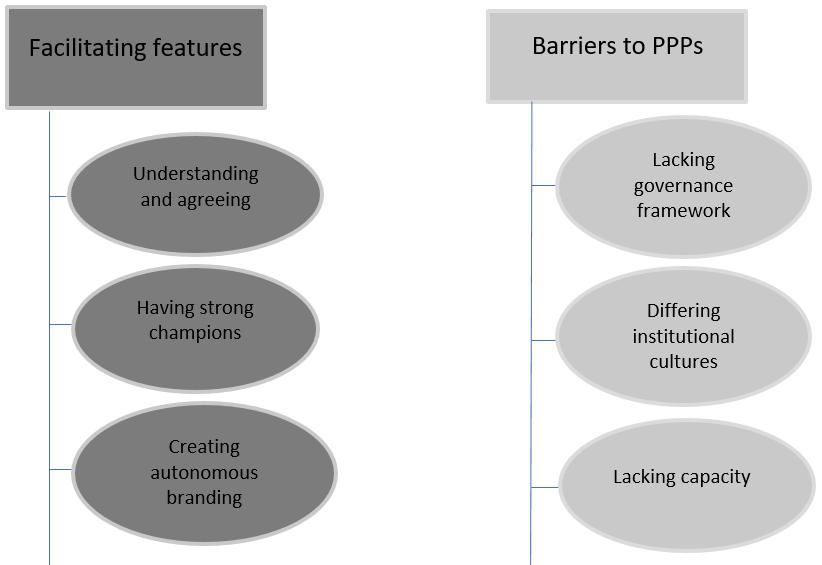

A number of themes highlighted the features of the PPP that enabled the RHTU to be effective. These facilitating features were (1) understanding and agreeing with the national plan for PPPs and maternal and child health, having strong champions, strong relationships and a formal decision-making body; and (3) creating autonomy and branding.

This PPP model of service delivery is a new concept in PNG; as such, there were also features that have created barriers to the RHTU effectiveness. The barriers to PPPs were found to be (1) lacking governance framework creating confusion in decision making and roles and responsibilities; (2) differing institutional cultures and ownership struggles; and (3) lacking capacity within the institutes themselves, particularly the National Department of Health. Figure 2 describes facilitating features and barriers to PPPs.

Figure 2: Thematic map of user comments about Reproductive Health Training Unit effectiveness.

Figure 2: Thematic map of user comments about Reproductive Health Training Unit effectiveness.

Facilitating features

1. Understanding and agreeing with the national plan for PPPs and maternal and child health: Fundamental to the initial establishment of the PPP were three key documents, which allowed discussions between the partners and an agreement on the focus of the RHTU. These documents included the Ministerial Taskforce on Maternal Health in Papua New Guinea3, The National Health Plan 2011–202018 and to a lesser extent the National Health Service Standards for Papua New Guinea 2011–202019. This third document was helpful in guiding the structure of the RHTU in partnering with provincial health authorities. Several other reports and national policy documents may have influenced the overall concept but these three documents were complete and clearly outlined the national agenda. Regardless of the confusion of setting up a PPP and the enormous number of logistical decisions negotiated in implementing a training unit and its courses, all partners knew, understood and relied on these documents to structure the PPP and the RHTU.

I think the strength of it is purely by the fact that all the partners are working together, to deliver on an agreed outcome, so we’re all working towards achieving the same outcome. It’s not only parallel, it’s in line with the National Health Plan, it’s in line with the government’s priorities, and it’s in line with the partners’ priorities. (Partner, 2015)

Furthermore, the push within Australia to engage in PPPs allowed the Australian Government to work within this partnership structure8.

We live in a different policy environment whereby public-private partnerships are a much bigger deal. People are starting to think more about what does it actually mean. So, I think some of it is about timing and about, certainly policy from our government. Policy has very much shifted to, that [PPPs] needs to be the focus of the programs. (Partner, 2015)

2. Having strong champions, strong relationships and a formal decision-making body: Having key champions in each organisation has been critical to the PPP and the implementation of the RHTU. Despite the transience of various roles, each of the partners had employees committed to ensuring that RHTU continued and passionate about its success.

I think you’ve got some good drivers in there [NDoH] … I do think they are genuinely committed to making this work. (Steering committee member, 2013)

I think a lot of the strength has been in the people that have been core to it. The people who have driven it … At the moment it is good relationships and it is good people doing those things, and it’s getting out there and delivering the training, so it’s working in an environment where we know lots of things don’t work. (Partner, 2015)

Part of the benefit of strong champions was the ability to build relationships over time within and external to the PPP, which facilitated the RHTU to continue to build momentum. Relationships were vital to the partnership structure, but also importantly between the RHTU and the provinces. Without relationships, the partnership could not reach its goals and outcomes.

Unless you know people in PNG nothing works. That is the main reason why nothing works. There is no use having process and protocols in PNG because these don’t work. Everything works based on personal relationships and interactions. So if these are good things may work and if they’re not good things just don’t work. So I’ve helped quite often in an informal way. Sometimes I can help by just talking to someone. (Steering committee member, 2013)

The relationships are important, and the people in the program have been critical to its success, which also brings us that level of risk. (Partner, 2015)

A decision-making body such as a steering committee (which was perceived as a necessary group, but struggled to be effective due to lack of decision-maker engagement) can allow key champions to influence the PPP in a positive way.

I think currently there’s good representation [on the steering committee]. We’ve got NDOH, there’s the UNFPA [United Nations Population Fund] that recently joined, and then we’ve got reps from the school of medicine as well as the chief specialist who’s on the committee as well. (Partner, 2013)

I think we’ve been meeting regularly since we started and a lot of discussions have been made during the meetings to discuss things like how the trainings are going, how the provinces are responding to the trainings, how we as a committee can make changes that we need to do to make people happy in the provinces. (Partner, 2014)

So, the RHTU Technical Committee is really important. …. We know what is current and it’s easy to make recommendations and just move forward with intentions. (Steering committee member, 2013)

However, representation from professional caregiver groups was always difficult from the very beginning and reflected wider professional status.

We have been disappointed by the lack of voice from nursing and midwifery. [Nursing representation] was present at every meeting and that was fantastic, but she did not feel able to speak up … It’s so dominated by the doctors, and the greater part of the workforce are nurses and midwives. (Steering committee member, 2013)

As time went on, representatives for different relevant groups of stakeholders were invited to be members; however, institutional changes in all three partners increased the demand on the steering committee, and the expectations of engagement by all partners was either not met or not encouraged.

At the Steering Committee meeting, very few people say anything. No one wants to speak up. But you can clearly see the dynamics happening [–] the most conversation occur[s] between two people. (Partner, 2015)

Regardless of the difficulties, having a decision-making body, with key champions from each of the partners and the wider reproductive health stakeholders, has enabled clearer lines of communication, issues and a reportback mechanism.

Creating autonomy and branding: The autonomy of the RHTU became part of the PPP’s success as it enabled the fast pace that being a non-governmental entity allows. While autonomy had its downsides, mainly ownership and sustainability issues, it allowed the PPP to enact its primary target of improving the competence of frontline health workers in essential obstetric care and emergency obstetric care service provision in partnering provinces.

The idea was to do this initiative outside of the Health Department, because in the Health Department you’re constrained by the lack of movement … Things are painfully slow and often times result in things being cancelled even after a whole year of preparation and planning which is a complete waste of time. So it was good not to have it in that environment. Then the PPP was a new idea and everyone was into it, it seemed like a good idea. (Steering committee member, 2013)

We have the NDoH, AusAID and Oil Search coming in, and when you really look at it, if RHTU has to be within the NDoH, we wouldn’t have the capacity to drive it, when you talk about logistics and managing the administrative side of it, it would take ages to do that. So, it needs to be a place where they can also manage the funds, logistics, communication and all that so it’s well coordinated. (Steering committee member, 2013)

The branding, while contentious, particularly for Oil Search Foundation, was recognised as also potentially affecting the uptake in the provinces.

They think Oil Search is coming in and telling us what to do, but they forgot it’s not Oil Search … My job now is to really make sure they understand the notion of PPP, and where we are coming from. (Steering committee member, 2013)

Now we have someone come here for reproductive health … we want the RHTU here [–] at least we know what they are doing. (Stakeholder, 2014)

The PPP is about our visibility amongst it all and making sure we get something out of that. When they go out they sell themselves as RHTU – the contention is are we getting enough out of that? [but] we think it’s a good model, it’s doing well. (Partner, 2014)

Branding as an autonomous unit also provided a structure fitting the policy directions of the NDoH and Australian Aid (DFAT) that was successful and potentially useful for the future.

I think, for us, there has been a gain probably in the branding, so for us, kind of a bit of shallow win, but incredibly important to be sitting in our seats. When we ever get asked about private sector, we can always pull out, ‘Oh, we’ve got the RHTU.’ So it’s been important for us in terms of branding and to say that we have a relationship with Oil Search, because it demonstrates that we are trying to engage in that space. Maybe we haven’t got the model right, but at least it’s rough, and I think that that’s important. (Partner, 2015)

Because we want to do this quickly, fast, and the pace that [RHTU] is going is quite fast. But I think in one way or another sometime in the future ... [we want to] take it as a national program. When that will happen I’m not sure. (Partner, 2014)

Barriers to the PPP

Data analysis resulted in three major barriers to PPPs in PNG.

1. Lacking governance framework creating confusion in decision making and roles and responsibilities: Decision making and reporting processes in the PPP were affected by uncertainty about roles and responsibilities, which in turn impacted on project implementation. This uncertainty was connected to lack of governance framework for the PPP as well as hesitancy in decision making and devaluing process outcomes.

People don’t seem to fully understand the whole concept of PPP as yet; even those who you think should understand … but the key point is the NDoH is pretty keen to work together with people, but there’s no framework, there’s no structure, so everything is very adhoc … there’s no governance around how PPPs should work, so I think everyone there is very hesitant to take that first step to make a decision. (Partner, 2013)

Throughout this whole process and because of changes in staffing, DFAT have seen different people engaging at different times and I know that’s been an issue, certainly on our side, it means you’ve got different people holding different parts of knowledge. From my engagement, I don’t have any real sense of how much the Department values its training. (Partner, 2015)

The structure of the different organisations exacerbated the problems of clear responsibility and reporting lines. For example, NDoH has two internal units who could potentially oversee the partnership; DFAT used an external organisation, Health and HIV Implementation Services Provider, for contracts and reporting, and Oil Search Foundation, a new entity itself, struggled with responsibilities between Oil Search, the Oil Search Foundation and the RHTU team itself.

The more people, the more complex it becomes. There have been issues about who is responsible. ... I know early on there was a confusion about who we were reporting to; to DFAT or HHISP [Health and HIV Implementation Services Provider]. (Partner, 2014)

RHTU is not the partner, RHTU is the vehicle by which the partners are engaging into it, so when the partners come up with ideas, the partners need to make a decision, as part of the Steering group on what that is. RHTU … does not make those decisions. (Partner, 2015)

The department is a big entity in itself, and there are lots of different people within the department who’ve got their own ideas about both in-service training and the types of training and that split between the HR branch on one side of the department, public health on the other. (Partner, 2015)

Changes within each of the partnering organisations, including strategic directions, also added to shifts in thinking of what the PPP should be and who the decision makers are.

And the actual process of going through to the concept the contract changes probably took about 6–8 months, and then the process of just trying to get it signed and AusAID reworking – I understand they were going through a lot of internal changes and accountabilities and needing things differently, but there wasn’t a great level of communication between that. No one’s fault particularly I just think everyone’s in the process of transition as organisations are, and Oil Search Foundation was at its inception, its infancy with all the teething problems associated. (Steering committee member, 2013)

2. Differing institutional cultures and ownership struggles: Some Papua New Guineans did not want to give up ownership and hand over to ‘external’ people the training of their own health workers. This struggle created barriers in implementation and also barriers to communications within the partnership. It also revealed individuals within NDoH who refused to engage in any decision-making processes.

My colleagues were a bit upset in the beginning – why are you doing this? I say I know, but you all have other things to do and we tried some of our ways and our trainings and we found that the link was not good so maybe let’s do it this way first and when we strengthened ourselves then we can get involved. And eventually this will be your thing. (Partner, 2014)

Often you get to a point in the planning process and there’s this one person who claims they haven’t been adequately involved in the communication process and they just throw a spanner in the wheel or stamp their foot and say it’s not happening. (Steering committee member, 2013)

… through the process of communication I’m telling already how I would see the benefits of the RHTU and how it would fit into how we are looking at the whole issue, but I don’t know if our partners know that, so that’s the gap and had I been to those [steering committee] meetings ... (Partner, 2015)

3. Lacking capacity within the institutes themselves, particularly the National Department of Health: For the most part, all interviewees agreed that the NDoH struggled with capacity to engage in the partnership. The busy NDoH has challenging processes and systems which mean they were often unable to make decisions quickly. On one level, this was a reason for introducing a PPP.

The Department of Health itself may not be in a position to provide the training because of shortage of staff or shortage of resources. So I see complementarity with the work that RHTU does with the Department of Health and obviously they are feeling a training gap that the country has. (Stakeholder, 2015)

However, on another level, this lack of capacity affected the power balance, overall implementation and ownership.

I think for the Department roles and responsibilities are quite long, it’s longer than the other ones. We at the department, we need to catch up to the other two partners. … So yes, it is working but what should be the major partner – NDoH – we are slow. (Partner, 2014)

The only person who signs stuff about this sort of stuff is the Deputy Secretary level at the very least. So he’s hamstrung by a long system of what they call process, which is really total disorganisation. It will take a long time for that to change, we are stuck with acknowledging that, recognising it and living with it. (Steering committee member, 2014)

Even though they’re part of it, it is really difficult to get that level of engagement. The people in the department are so busy. They have so many demands on them. They have their own jobs to do, and then they have multiple donors and development partners constantly combing them out. (Partner, 2015)

While the NDoH was often pointed to as lacking capacity, the other partners had their own fluctuating strategic directions, staffing changes, and policy environment shifts that need to be noted as challenging the effectiveness of the PPP.

I think that’s a lesson learned that it’s not good to have two start-ups held up together with one managing the other before they know how to manage themselves. (Steering committee member, 2014)

DFAT has been going through its own internal challenges. The HHISP process has from my perspective been constantly changing the goal posts, and the M&E [monitoring and evaluation] framework being in a state of flux all the time, the lack of feedback on the reports, the financial side has been erratic; and I don’t think that DFAT’s role on the Steering Committee has been very strong. And I think that’s just because they’ve got so much else happening at the moment, organisational change, as are we, as is NDOH. (Steering committee member, 2014)

Oil Search Foundation had only been established a year when the RHTU was set up, which meant their capacity was also challenged and what started as a contract with AusAID shifted to DFAT when a new Australian Government was elected.

Discussion

The overall impressions of the PPP in PNG were positive and negative and drew on a historical perspective, informal conversations, and tracking of individual perceptions over time6,25,31. Features of the PPP that facilitated the RHTU functions included agreement on the maternal and child health needs of the country; passionate, motivated advocates; and a partnership that enabled a speedy scale-up of the training unit. Barriers included the lack of a governance framework to guide roles and responsibilities as well as institutional cultural differences and ownership struggles. Furthermore, as a new model for PNG, the PPP revealed capacity issues and instability within the partners themselves, particularly the NDoH.

Defining characteristics of other successful PPPs have been reported to include cooperation; long-lasting relationships; sharing of risks, costs and benefits; and mutual value addition32. Furthermore, having firm policies with which to help structure and guide a PPP has been noted by other PPPs in PNG10 who advocate for stronger PPP policies. For this PPP, guiding policies were not only creating the partnership but also defining the ultimate goal of the partnership to implement a training unit, which allowed for a firm basis for all the partners’ agreement. Other PPPs have also found that success can be driven in the initial few meetings and that documents exchanged between stakeholders must articulate motivations and define the scope of the project33.

This qualitative evaluation found that strong champions in each partnering organisation informally advocated for the PPP, which helped build relationships and kept momentum. Tang also found that stakeholder relationships are critical to the success or failure of a PPP in any sector33. Open and effective communication between partners is fundamental throughout all stages of a PPP but especially at the beginning. However, for PPPs to be effective, it is also important to reduce not only the power asymmetry between partners but the reliance on informal mechanisms of coordination and trust on which PPPs rely17.

This PPP was set up as one of the first service delivery PPPs in PNG in an environment where, historically, PPPs equate with projects for building infrastructure. The stakeholders were varied, with complex multiple layers within each institution, and separate agreements between NDoH/DFAT and NDoH/Oil Search Foundation making up the PPP. Instability within each organisation necessitated a governance framework to guide the partnership and delineate roles and responsibilities, which was never developed. Successful PPPs require careful contract structuring and detailed specifications for roles and responsibilities of each partner20,34.While there is a Public Private Partnership policy 20089 and a new Public Private Partnership Act 2014, both focus on partnerships for infrastructure rather than service delivery and therefore do not provide appropriate guidance for a PPP such as this one.

One of the major risks related to the relationship between organisations is an unbalanced power relationship17; this can be exacerbated by a lack of clearly defined roles. These undefined roles were found to be a barrier in this PPP. The concern for ongoing ownership and the lack of capacity in the NDoH revealed an unbalanced relationship, which was an ongoing source of tension. It has been recognised in other PPPs that the reason for partnering is because the private sector can achieve better efficiency through experience and innovative systems17, a finding that does not sit easily with large government bodies.

While provincial authorities are responsible for implementing primary healthcare programs, the NDoH is responsible for ensuring that national policies, standards and protocols are followed. Previous studies have highlighted that there is a concern the NDoH has no effective oversight of health programs on the ground that allow it to ensure national polices and standards are followed10. These concerns are addressed in this PPP through the endorsement by the NDoH of the RHTU courses, allowing the provincial health authorities to accept the RHTU.

Conclusion

The findings of this qualitative evaluation confirm what has been found in other PPPs, even though this is a different model – providing service provision rather than infrastructure. The set-up stage is vital for forming a strong structure and governance framework that can weather organisational changes and changing policy environments. Strong champions who are able to advocate for and build relationships are vital, although they also pose risk by tapping into informal networks and structures35. Importantly, ownership of the outcomes and future sustainability require constant balancing of power between the partners and full engagement from the public partner.

Further research into how to overcome power imbalances between partners in a PPP as well as setting up a governance framework in a dynamic environment could further inform this growing area of collaboration between the private and public sectors.

Acknowledgement

Acknowledgements are given to all the stakeholders, including partners in the PPP, for sharing their knowledge and time throughout the monitoring and evaluation process of the Reproductive Health Training Unit. This work was supported by the Oil Search Foundation, who contracted WHO Collaborating Centre to provide external monitoring and evaluation of the Reproductive Health Training Unit.