Introduction

Throughout the world, particularly since the mid-1980s, a movement has been growing to ensure the education of health professionals meets the needs of the population and of health systems1-3. Various international authorities have emphasised to produce competent doctors and highlighted the need for a review of medical undergraduate curriculum to meet the criteria and challenges of community-orientation of medical education (COME)2,3. In order to meet these challenges, medical schools are now looking to the community at large as a reference point for their curricula, with an emphasis on organising teaching students in community settings and teaching more about community issues1,3,4. It has been suggested that, to produce need-based and community-oriented doctors, a sociological perspective must be added to the traditional biomedical approach of medical schools. Many schools have completely restructured their curricula with a community-oriented approach1,4,5 and others have made significant changes by introducing community integration, problem solving and community-based activities into the curriculum1,2,5. Community-based education (CBE) has been widely advocated, ensuring achievement of educational relevance to community needs and, consequently, the implementation of a COME program3,4.

In the past three decades, medical education in Bangladesh has experienced many challenges and changes. Among them an important initiative has been the implementation of community-based teaching (CBT)6-11. There is now a general acceptance among the teachers and students of the medical colleges that the approach is an effective strategy to adopt, if the health needs of the people of Bangladesh are to be met10-12. However, there is still limited evidence of community orientation in the undergraduate medical curriculum6,7,13. To produce needs-based doctors, it has been suggested that medical education needs to be overhauled14.

In Bangladesh, the main community-based activities used to attain community orientation in the curriculum were effectively developed and implemented by the Further Improvement Medical Colleges Project (a Government of Bangladesh/World Bank/WHO/Department for International Development project) in 1997–1998, which included the following programs6,15,16:

- residential field-site training (RFST)

- urban demonstration area

- study tour

- primary care teaching in hospital outpatient departments.

In the 2012 Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) medical curriculum, the structure of COME was rescheduled as follows17:

- community-based medical education: 30 days

- day visit to community health centres: 10 days

- RFST: 10 days

- study tour: 10 days.

Study tour

A study tour is a travel experience with specific learning goals in which the majority of academic work is completed as a homogeneous group travelling outside their own medical campus. It provides a group of students an applied and supervised experience at an off-campus domestic location for a minimum of seven nights. Once on site, travel during the study tour is an integral part of the learning process.

Study tours offer groups of students a unique educational experience that includes visiting healthcare facilities, including various multidisciplinary institutes, participating in their demonstration, excursions and special events conducted in the local community.

Aim of the study

The study tour provided the opportunity to visit health-related and other organisations of Bangladesh for acquiring knowledge and developing skills in assessing health needs and demands of the population. The study tours are organised for the third year and fourth year (according to the old curriculum) students to visit the public health related important places and organisations including primary and secondary healthcare centres. The aim of the study was to examine the views and experiences of the medical students of the Uttara Adhunik Medical College (UAMC), Dhaka, Bangladesh regarding the structure, facilities, learning experiences, strengths and limitations of the study tour they undertook as a requirement of the community medicine course.

Methods

Study participants

The cross-sectional survey was conducted among the medical students studying at UAMC (one of the well-established private medical colleges situated at the outskirts of the capital city, Dhaka) at the time of their curriculum-assigned visit to community facilities. Respondents were approached as well as chosen conveniently and a total of 135 students were recruited for the study. All the eligible students from UAMC batch 6 (UM-6) (fourth year), UM-7 (third year) and UM-8 (third year) were the participants.

Organisation of study tour

The study tour was headed by two faculty members from the community medicine department and took place on 1–6 April 2016 for UM-6 (n=51) and UM-7 (n=48), and 4–9 January 2017 for UM-8 (n=36). Students and parents were briefed about the aims, procedure and management of the study tour before the tour. The study tour was scheduled at Cox’s Bazar, Chittagong, a tourist city situated in the north-east part of the country and approximately 400 km from Dhaka. Three faculty members and other supporting staff accompanied the students.

Visits to healthcare centres and other organisations

Students were required to collect the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) health indicators and data/statistics of the health centres and organisations they visited for their summative reports and poster presentations to be submitted/organised at the end of the tour. The students visited the following facilities.

Chakoria Health Complex (day 1): The UAMC team visited the Chakoria Upazila Health Complex (subdistrict hospital), which is a 50-bed hospital with two union subcentres, 15 union health and family welfare centres and 43 community clinics. The catchment area of the health complex covers approximately 503 km2, 83 155 households and a population of 510 105 people.

Cox’s Bazar Medical College (day 2): Cox’s Bazar Medical College is a government institute that was established in 2008. It enrols 60 students every year and offers a 5-year MBBS course. It has a 250-bed teaching hospital where the students do their internship after completing the MBBS course. It has all the major branches of medical education.

Meteorology centre and radar station, Cox’s Bazar (day 2): Students were briefed about the weather instructions (forecast and warning) including implications of climate change, and shown all the meteorological instruments and materials. At the radar station, students received a computerised demonstration of the weather, its forecast and warnings.

Ramu Health Complex (day 3): Ramu Health Complex is a 31-bed hospital with two union subcentres, seven union health and family welfare centres and 23 community clinics. The catchment area of the health complex covers 391.71 km2 and a population of 289 775 people.

Follow-up activities

Post-visit sessions: A reflective question-answer session and post-visit photo exhibition and poster presentation were held, where faculty and students attended.

Questionnaire to seek students’ feedback: A questionnaire was developed by one of the authors (MAAM), and teachers of the community medicine department reviewed and approved the questionnaire. Data were collected using this self-administered questionnaire and were analysed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v24 (IBM; http://www.spss.com) and Microsoft Excel. The questionnaire has four sections: (1) background information, (2) arrangement for the study tour, (3) perceptions regarding study tour organisation and experiences and (4) open-ended question regarding study tours.

Report on study tour: Each student was asked to submit an individual report that was considered a prerequisite for sitting the second professional MBBS university examination.

Examining study tour information: Each student was asked to write an individual study tour report, which was considered a prerequisite for sitting the second professional MBBS university examination.

Ethics approval

Both the study tours were approved by the Academic Board and Ethical Review Committee of UAMC, Dhaka, Bangladesh (UAMC/ERC/Recommend-58/2017).

Results

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

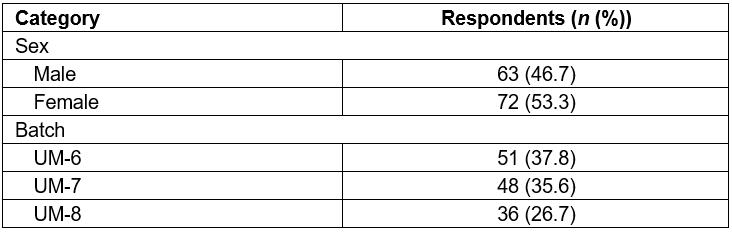

Table 1 shows that more than half of the respondents were females and the majority were from UM-6.

Table 1: Demographics of respondents (n=135)

Questionnaire findings

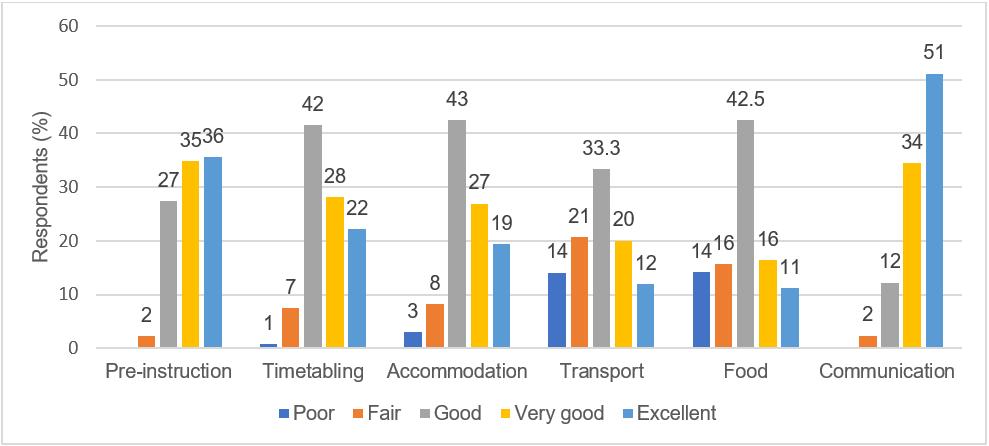

Perceptions of students regarding study tour: The majority of the students scored the pre-instruction of the study tour as ‘excellent’ (35.5%), and timetabling (41.5%), accommodation (42.5%), transportation (33.3%) and food (42.5%) as ‘good’ (Fig1). More than half of the students reported the communication with teachers and staff as ‘excellent’.

Figure 1: Students’ perceptions regarding arrangements of the study tours.

Figure 1: Students’ perceptions regarding arrangements of the study tours.

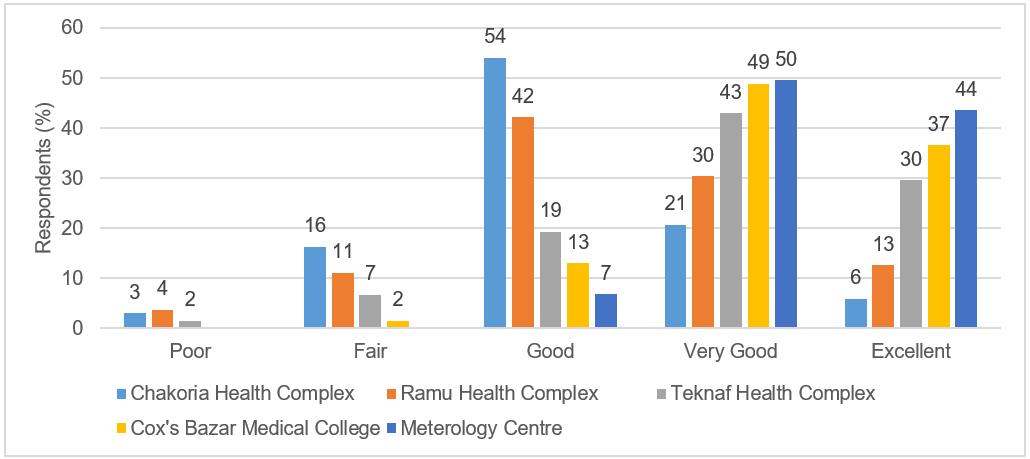

Perceptions of students regarding visit to health centres: Figure 2 shows that more than 85% of students found their visit to Cox’s Bazar Medical College either ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’. The meteorology centre was also rated by most students as ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’.

Figure 2: Self-reported experience of the respondents (%) of health centre visits.

Figure 2: Self-reported experience of the respondents (%) of health centre visits.

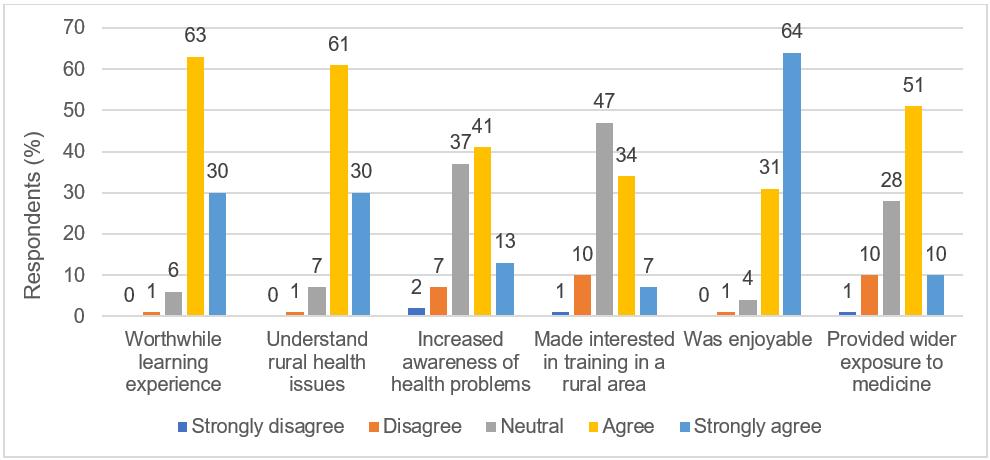

Students’ satisfaction regarding study tour: The majority of the students agreed or strongly agreed that the tour was a worthwhile (93%) and enjoyable (95%) learning experience that helped them to understand rural health issues (91%). More than half of the students reported that the study tours increased their awareness about common rural health problems (54%) and provided a wider exposure to medicine (61%). Only 41% of students reported that the study tour increased their interest in undertaking training in a rural area (Fig3).

Figure 3: Students’ satisfaction regarding study tour.

Figure 3: Students’ satisfaction regarding study tour.

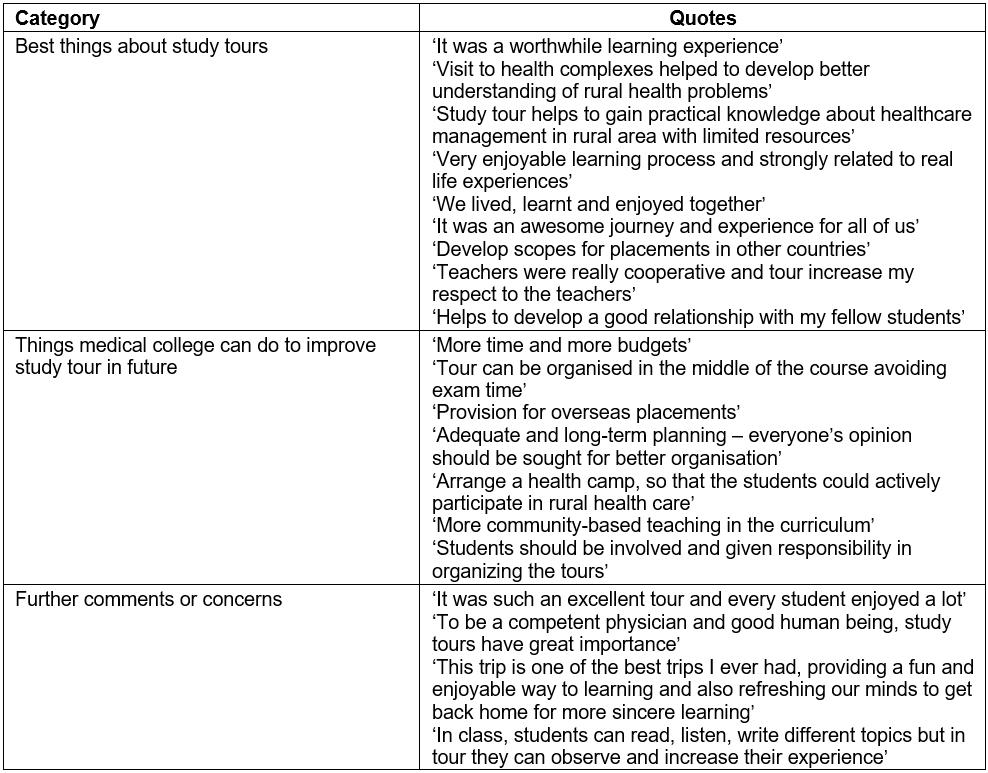

Open-ended questions: Students were asked to highlight their experiences, suggestions and concerns about the study tours by answering three open-ended questions. The key responses of the students are shown in Table 2. Students appreciated the usefulness of the tours and mentioned that they developed a ‘better understanding of rural health problems’, which were related to ‘real life experiences’. They recommended more provision for community-based teaching in the curriculum and mobilisation of adequate resources for better implementation of the program.

Table 2: Students’ remarks regarding study tour experiences

Post-visit photo exhibition and reflection of experience of the study tour

The tour program was celebrated by the students in a photo exhibition held on the college premises. They displayed every moment of the trip using photographs and a poster presentation and also hosted a question and answer session. All teachers and students were invited to attend the photo exhibition. The session was appreciated by all those attended.

Assessment of the study tour

Each student wrote an individual study tour report, the satisfactory completion of which was a prerequisite for sitting the second professional MBBS university examination. Students were asked study-tour-related questions during oral and practical examinations.

Discussion

The questionnaire results show that study tours provided opportunities for students to visit healthcare centres far away from capital city, collect MDG health indicators (maternal mortality rate, infant mortality rate, fully vaccinated children, stillbirth rate, antenatal care, etc.) and as a result develop an understanding of common rural health problems (Fig3). Students also visited one of the peripheral medical colleges and were able to compare the disease patterns, categories of patients, referral system, resources and facilities with those of their teaching hospital and locality. Although students expressed their satisfaction about the organisation of the tours and visit to the rural health centres (eg pre-instruction timetabling, accommodation, transportation, food, and communication with teachers and staff), a substantial number of students expressed their concerns regarding some aspects of the study tours (eg planning, duration, resources, finance, food and accommodation). This feedback will be carefully considered to make tours more effective for maximum student benefit from their CBT experiences.

Through their involvement in the study tour, students developed greater insight about the organisational and operational aspects of primary and tertiary care hospitals (eg human resources, infrastructure of the complex healthcare provisions, patient categories, disease patterns, inpatient and outpatient services, and outreach services). They also gained an idea of the common diseases prevailing in rural and semi-urban areas. The visit to the local meteorology centre and radar station raised their awareness of environmental health (air, water, noise, soil, meteorology, climate change, etc.), which constitutes a major portion of their community medicine curriculum. This is important because Bangladesh is highly vulnerable to natural disasters and public health issues as result of climate change18. Students were also required to collect maternal and child health related health data and statistics – this exercise helped them to understand the burden of infant and maternal mortality, both of which are still high in Bangladesh19.

In the present study, almost all students agreed or strongly agreed that the tour was a worthwhile learning experience, helped them to understand rural health issues and was an enjoyable experience. More than half of the students reported that the study tour increased their awareness about common rural health problems and provided a wider exposure to medicine. A study conducted by Salam and Yousuf12 in Bangladesh examined the views of medical students and teachers about RFST, one of the mandatory community-based teaching programs prescribed in the medical curriculum. A majority of students (78–98%) and teachers (88–96%) felt that RFST increases students’ awareness about common rural health problems, inculcates a caring attitude and helps to develop required generic skills to practise medicine. A well-planned CBE program exposes students to different groups of people, encourages students to develop empathy for unserved sections of people in the community, helps them to learn about social norms, values, beliefs, problems, prejudices and poverty, and develops their understanding of implications for health care and quality of life20. Moreover, the approach increases the understanding of health professionals regarding ‘rural power structure and its impact on health and illness (p. 59)’20.

An important and worrying finding of the present study was that 59% of students were not interested in training in rural areas and 46% of the respondents felt that the tour failed to increase their awareness of common rural health problems (Fig3) – all of which need careful consideration while designing and implementing CBT programs. This may be due to the short exposure of students to semi-urban healthcare facilities rather than real rural facilities. The authors found similar negative attitudes of the medical students of Bangladesh in their previous career choice study: only 12% of medical students were interested in pursuing a career in basic sciences and preventive medicine, 10% wanted to practise medicine in rural areas, 33% opted for government jobs and 51% expressed willingness to move abroad21,22. The most common discouraging factors for medical students towards working in rural and remote areas include lack of good working conditions and personal, academic and professional development, inadequate allowances and incentives for rural posting, and lack of communication and connectivity20-24. Another study conducted with medical teachers in six private medical colleges in Bangladesh reported that 68% were dissatisfied with the present implementation of the undergraduate curriculum, and they recommended a review of the curriculum to include more community-oriented and competency-based elements to produce better doctors for the community25.

There is an urgent need for a major review of the medical curriculum toward more effective community orientation to expose students to healthcare problems in rural settings21,22,24,26. Community-based education provides community orientation, which helps students to gain experience in primary care and to encourage them to enter the area3. Community orientation enables the students to relate theoretical knowledge to practical training and gives them a sense of social responsibility by helping them understand the needs of a local community3,20. Longitudinal and multidisciplinary community-based learning programs in the curriculum broaden student education by offering a community perspective of health and disease and help students to develop primary healthcare and public health competencies needed for their future professional life serving unserved and underserved communities27,28. Appropriate career counselling and perhaps government policies are needed to offer some rewards/inducement to attract graduates to practise in suburban and rural settings21,22,24,26. Examples of incentives to attract and retain doctors in rural areas include opportunities for academic and professional development, increased allowances and incentives for rural posting, transparent and fair promotion policy, study assistance for postgraduate education, connectivity between rural and urban health facilities, improved working conditions, and evidence-based, transparent and fair national policies on rural posting and retention21,22,24,26.

A comprehensive and integrated curriculum needs to be developed and health-related sites identified for CBT programs such as study tours, RFST, rural placement and urban demonstration areas1,3,9,10. Prior teaching and proper orientation for study tours would have to be provided to the students. Students could be asked to maintain a diary during their rural visit and to submit a reflective portfolio after completion for assessment, which would carry marks contributing to final grades. Summative examination, both written and oral, could include questions related to study tours, not only on community medicine, but also in other subjects. Study tours should not be considered as a ‘pleasure trip’, and less emphasis should be given to visiting tourist attractions. Other elements of COME prescribed by the Bangladesh Medical and Dental Council17 and the Further Improvement Medical Colleges Project15,16 should be implemented in all medical colleges. The medical education authorities and policymakers should pay special attention to the provision of CBT throughout the undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum as discussed above1,3,27,28.

The present study aimed to investigate the views and experiences of medical students regarding the organisation, management and learning experiences of study tours. This cross-sectional study involved only one private medical college based in the capital city and had a small sample size; therefore, caution needs to be taken to generalise the data in other settings. More long-term follow-up research should be conducted targeting both public and private medical colleges of the capital city, Dhaka, and outside.

Conclusions

Overall, the study tours had a positive effect – enhanced students’ awareness and understanding of common rural health problems. As study tours failed to increase the motivation of the students (59%) to work in the rural areas, CBT in medical curriculum should be reviewed and implemented using effective and evidence-based models to promote interest among medical students to work in rural and underserved or unserved areas. COME, which prepares medical students to become more effective practitioners, is now a global movement. Many medical schools around the world have adopted COME as the main curricular framework in order to align learning programs with the needs of the community and the learners. Medical curricula in Bangladesh should allocate time and resources to offer CBE in various forms and models to promote an understanding of common health problems in rural areas. Appropriate policies and specific incentives should be developed to attract and retain doctors in rural and underserved or unserved areas.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the students of UAMC who helped and participated in the study.