Introduction

Emergency departments (EDs) and urgent care centres (UCCs) deliver a broad range of services and are often the first point of contact for people experiencing mental illness1,2. In Australia, a higher proportion of mental illness is reported for populations residing in inner and outer regional areas (IOR) when compared with major cities3. Conversely, IOR areas are serviced by fewer psychiatrists, mental health nurses and psychologists when compared to major cities indicating that consumers in rural areas have poorer access to specialist mental health services than their metropolitan counterparts4.

Generalist nurses working in rural EDs and UCCs are frequently required to assess and provide treatment for consumers presenting with mental illness, often with limited support from mental health specialist services and no formal training1,5. Australian studies reporting on the experience of rural generalist nurses in providing care to mental health consumers indicate a lack of clinical skills, mental health knowledge and support compounded by a fear of managing mental health presentations1,5. Additional issues documented for emergency nurses in metropolitan areas includes ambiguity surrounding mental health triage, the challenge of managing aggression, time constraints and the impact of the emergency environment on mental health consumers6-8.

The use of telehealth mental health services in Australian rural hospitals has improved access to specialist services for mental health consumers presenting to emergency departments, but offer limited onsite support to nurses working in EDs or UCCs9,10. Clinical education for generalist nurses has proved to enhance clinical confidence, skills and self-efficacy in managing mental health emergencies for a period of time11-14. Targeted case-based training has also reported to improve emergency nurse competency for managing specific presentations15. However, studies evaluating training provide little information regarding the long term maintenance of confidence, knowledge and skills obtained by participants from single educational initiatives. Other interventions include the integration of a mental health nurse practitioner in an ED, which has not been explored within rural EDs or UCCs16.

Gaps in the research: the experience of rural generalist nurses

Despite the exploration of potential strategies, few studies have documented the experience of rural generalist nurses in assessing and treating mental health consumers in rural EDs and UCCs. The impact of delays in transferring mental health consumers to inpatient facilities on the workload of rural generalist nurses is unknown. To the authors’ knowledge, there are no studies utilising a descriptive qualitative approach to explore the management of acute mental health presentations by generalist nurses in small rural EDs and UCCs with limited onsite outpatient services and access to inpatient facilities within Australia.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive qualitative design was applied as the study framework. Principles of naturalistic inquiry were utilised such as the use of a natural setting (ie interviews conducted in hospital) and the generation of data through mutual contextual understanding between the participants and primary researcher who was also a rural emergency nurse (ie tacit knowledge)17.

Sample selection

Participants were purposively sampled. Registered and enrolled nurses who were employed by the participating hospitals to work in ED or UCC on any basis (casual, full-time or part-time) were invited to participate in an interview. Student nurses were excluded from the selection criteria. Sites included one rural emergency department and two urgent care centres located between 90 and 110 km by road from the nearest regional hospital with a mental health inpatient unit in south-west Victoria. All sites had access to a community mental health team during business hours but had limited or no onsite support after hours. Telephone triage services based at the nearest regional hospital were accessed by all sites after hours. Only one site had occasional face-to-face assessments conducted after hours by a local mental health clinician.

Sample recruitment

A letter of invitation to participate in the study was distributed by the Nursing Unit Manager (NUM) to eligible nurses. Interview times were arranged by the NUM or directly with the primary researcher. As the primary researcher had rapport with potential participants at one site, it was necessary to distance the primary researcher from the recruitment process.

Data collection

Informed consent was obtained from 13 nurses meeting the sampling criteria. Participants completed a one-page demographic questionnaire and participated in a semi-structured interview face to face within the hospital setting with the primary researcher. An interview guide developed from a review of the literature was utilised, exploring the domains of experience, clinical confidence, safety and knowledge.

Interview duration ranged from 18 to 45 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were emailed to participants for their review as a means of establishing face validity. A journal was maintained by the primary researcher, to document reflections immediately after conducting the interviews and consider the role of the researcher context on data collection18. Reflections included observations about the participants, interactions (ie whether they appeared comfortable during the interview), emerging concepts for consideration and whether the assumptions held by the primary researcher about the phenomena of interest were challenged.

Data analysis

De-identified transcripts were imported into NVivo (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com) for analysis. Researchers independently engaged in an initial reading of the transcripts to ensure data familiarisation19. Line-by-line coding was conducted on several interviews. First cycle coding was descriptive in nature and used to develop a coding framework, which was discussed and reviewed by the second researcher as a means of establishing internal validity20. Second cycle coding involved developing axial codes and interpreting emerging concepts within the context of participant demographics20. Through discussion between the three researchers, re-reading of the transcripts and analysis of the literature, themes were developed from the data19. Reflections documented by the primary researcher were also discussed with co-researchers during the data analysis and interpretation process.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from Alfred Health (HREC/17/Alfred/25) and Deakin University (2017-074). The familiarity with potential participants at one of the study sites was disclosed to the reviewing human research ethics committees.

Results

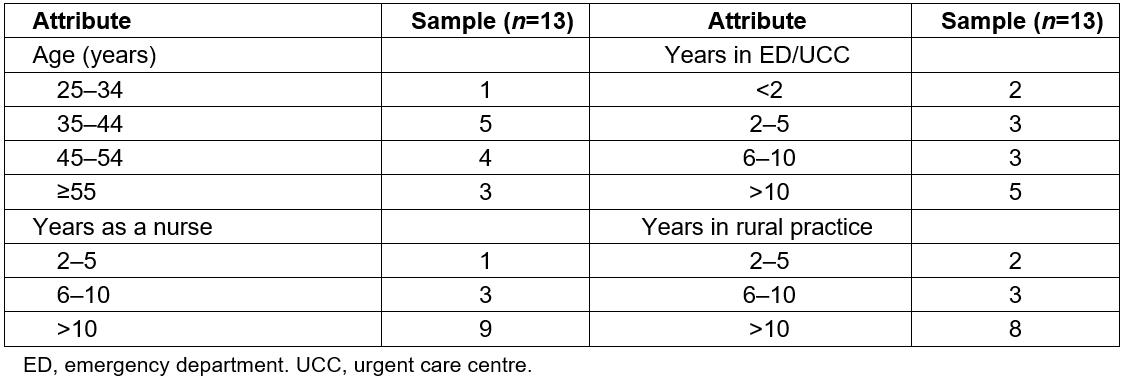

Participants were female registered nurses without postgraduate mental health qualifications. The majority of participants had more than 10 years’ experience as a nurse and in rural practice (Table 1). All participants, excluding one, had completed an undergraduate mental health placement. Two participants had previously been employed in a mental health and drug rehabilitation setting. The primary researcher had rapport with four participants from one site, one of whom was the NUM.

The findings provided insights into the experience of a sample of rural generalist nurses in managing acute mental health presentations, eliciting four key themes: (1) ‘we are the frontline’, (2) ‘doing our best to provide care’, (3) ‘complexities of navigating the system’ and (4) ‘thinking about change’. Multiple subthemes were developed in order to describe the various aspects of the key themes.

Table 1: Participant demographics

We are the frontline

Challenges associated with working in the rural context underpinned the narratives shared by participants. Managing multiple emergencies with little support was highlighted. Participants (denoted ‘P’ below) felt strongly about being the main provider of emergency care within their hospital.

Being rural: Irrespective of the nature of presentations, having limited resources including experienced staff and support personnel was frequently cited as a key challenge to working in the rural context.

It’s hard for small rural places to get enough staff as it is, much less in urgent care… (P08)

… you don’t have a huge amount of staff in or out of hours. (P04)

Knowing local issues and community members, particularly those who frequently presented to the hospital seeking care, was another aspect of rural practice.

Maybe the beauty of a little town is that they can keep a bit of an eye on you … which can be a good thing. (P12)

Managing multiple emergencies: Regardless of local mental health team availability, participants reported having to triage, assess and provide treatment to mental health consumers in addition to managing other consumers with medical presentations.

… regardless of having psych services there, you’re still the frontline cause you still have to do that initial assessment and then call psych in cause it’s never an instant that they’re here … (P03)

… it is hard when you’re down here by yourself, especially when you’ve got other patients here. Sometimes you can have three bays, three bays full and then you will have the police bring in a mental health patient … (P07)

Receiving limited support: Reliance on other hospital staff (eg porters, hospital security) for assistance with managing mental health presentations was discussed. A sense of vulnerability in working alone was communicated. One participant conveyed an appreciation for a male presence when managing difficult behaviours.

… we have night porter or security but they’re not really security trained but they are a presence, male presence that helps you … (P10)

… we only have an orderly … you know like they’re a cleaner, come, an orderly. They’re not security so we rely heavily on the police … (P08)

Dependence on other emergency services for assistance was discussed by the majority of participants. Police were identified as a limited resource and could not always offer assistance due to attending other emergencies within the community.

Paramedics, great, always. They’re always very helpful and they won’t leave if they think it’s not safe for us. (P13)

… once I’ve rang the police and they’ve said no that they can’t come up … (P03)

Additional personnel could also escalate situations due to a lack of mental health competency and perceived intimidation.

… the police have usually stayed, which doesn’t always make for an ideal environment too. It can sort of be quite threatening for the person … (P02)

Doing our best to provide care

Despite working in an environment with limited support, the majority of participants indicated that they provided the best care possible to consumers presenting with acute mental health issues.

Observations: Participants reflected that the majority of presentations they managed were drug or alcohol related, consisted of self-harm or suicide ideation. Overdoses and high prevalence disorders, such as depression, were also frequently managed. More experienced participants could reflect on how drug use and adolescent mental health has become more of an issue in their rural community.

… we have a huge amount of drug affected presentations … but a lot of mental health are already drug affected whether or not it comes with them trying to manage their symptoms … (P04)

We’d probably get a lot more younger overdoses … fourteen, fifteen year olds … just that peer pressure and that bullying that’s escalated … (P08)

Certainly seeing more mental health than we use … now we are seeing more of the drug induced, drug related or post-traumatic stress mental health issues ... (P01)

Challenging skills and knowledge: Lacking the clinical skills and knowledge to assess and manage mental health presentations resonated with the majority of participants. Mental health was regarded as a specialty field requiring a different set of skills to those utilised for other emergency presentations.

There’s no way that I would assess someone and consider them safe if they were threatening self-harm [because] we haven’t got that expertise … We need an expert to come in and make that judgement. (P10)

… when it’s not suicide and it’s something more complicated, I find it hard … you’ll think you’ve done a good job and then you’ll walk away at the end after being told how you should of handled it … mental health is so different … (P03)

The majority of participants, excluding the two participants with clinical experience in mental health, regarded their mental health knowledge as minimal particularly regarding complex mental health disorders, psychiatric medications and appropriate clinical questions.

… am I asking the right question, am I going to say something to trigger them? (P01)

When managing challenging behaviours from mental health consumers or drug affected consumers, the majority of participants could reflect on situations where they felt uncomfortable or intimidated.

on the inside, I usually get quite nervous but I think I tend to kind of like back away … (P09)

… she threatened us and stuff. So I rang the police to walk me back to my car … (P03)

I was unable to take any obs or anything because she was punching out at every one and kicking … so I was keeping my distance … (P10)

Participants were divided when asked whether their communication approach differed between mental health consumers and other emergency consumers. A greater awareness of non-verbal communication was indicated when approaching mental health consumers.

I know I approach them completely different to you know another patient that’s not mental health. You’re just a bit more wary of the potential for risk I guess … depending on their situation, the way you speak to them is a bit different. (P06)

Humans are so instinctual to another person’s behaviour and how we approach them … when someone comes in physically it’s easy [because] you just have the steps, but when it’s a behavioural thing, you’ve got to navigate that whole, that unknown territory … (P12)

Experiencing frustrations: Participants were vocal regarding the multiple frustrations encountered when providing care to mental health consumers. At the core of frustrations was a perceived insufficiency to provide consumers with an appropriate level of care. It was acknowledged that people presenting to EDs and UCCs are seeking help. Lacking time to build a therapeutic relationship with consumers was also cited as a frustration.

People who are presenting to a hospital with an issue, a presentation that is related to mental health, must be really wanting some help, some support. (P02)

Non-physical symptoms take more time too … you need to build a rapport and it’s hard to make someone feel like you care about them when you’ve only got a couple of minutes. (P13)

Other issues included managing frequent presentations and consumers who would abscond whilst awaiting review or transfer to a mental health facility.

So we end up having to hold patients here, we had a patient a couple of weeks ago and he ended up absconding three times, because they had a bed, then they didn’t have a bed, they had a bed, then they didn’t have a bed … (P04)

Complexities of navigating the system

Additional frustrations resulted from navigating the mental health care system and coordinating the care of consumers presenting with acute mental health issues.

Shortfalls of telephone triage: Whilst acknowledging that local mental health teams were strained, the majority of participants regarded after-hours telephone triage service as not appropriate for assessing consumers and dependent on the verbal communication of the consumer. Experienced nurses could reflect on how the introduction of telephone triage removed the onsite support offered by a local mental health clinician to the consumer and staff after hours.

… people can say anything on the phone, I’ve seen them do it through the window while they’ve been on the phone. Laughing with their friends that are in the room, that the mental health clinician doesn’t know that they are there … (P13)

I don’t think that an assessment over the phone is the correct way to assess a patient who has presented with any kind of mental health [issue] and I think that stuff is missed and we are discharging patients who are arriving back … (P04)

… I rang psych … but that was just a phone consult as well, they didn’t come and see her. She was expecting somebody at least to come in and see her. (P07)

Inconsistencies between the telephone triage and nursing staff were discussed by the majority of participants as a potential source of conflict. Issues surrounding privacy and the refusal of telephone consults were also cited.

… to try and convince them that they have to talk to someone on the phone … you’ve got to say, ‘I’ve just got this mental health worker on the phone that wants to talk to you’ and they are like ‘but there’s nothing wrong with me, why do I need to talk to them’, so they refuse … (P03)

Coordinating care: Limited after-hours onsite mental health support resulted in a greater reliance on the nurse management of the consumer with the support of a medical officer. Sometimes medical officers were junior or overseas trained with little mental health experience, requiring nurses to be proactive in directing doctors to policies and guidelines, particularly regarding chemical sedation.

… sometimes our GP registrars don’t have, or our more junior GPs as well, don’t have a lot of experience in mental health … (P11)

often we have doctors who are even at a loss and they’re relying on our guidance so that puts an added pressure on us as well and they need a lot of encouragement from us to talk to the clinicians themselves … (P02)

Participants felt that managing mental health presentations during business hours was less problematic than after hours as local mental health clinicians were able to conduct face-to-face assessments and formulate a plan for consumers. Overall the skills and support of local mental health clinicians were valued.

… during hours … the management I guess would be a lot easier than after-hours because … mental health are there … (P06)

… particularly happy when one of the psych nurses come in … they are our resource and we do call them in a fair bit. (P10)

Coordinating assessments for presentations with drug, alcohol and mental health issues was a challenge cited by a few participants.

We argue that it is still a psychosis no matter what caused it, they still need something but mental health don’t want to know about it because it’s a drug and alcohol and drug and alcohol don’t deal with mental health outside of it … we’re caught in the middle … (P01)

Transferring consumers: The difficulties surrounding the transfer of rural consumers to an inpatient mental health facility highlighted another aspect of a complex mental healthcare system. Transferring consumers for further assessment and treatment was considered particularly problematic after hours. Coordinating transport with the ambulance service and organising a bed were key issues.

… our ambulance service are hesitant to send an ambulance crew in the middle of the night or after- hours … because it takes an ambulance crew out of town and leaves us with one officer. (P01)

Participants felt like they were caught between services and they experienced pressure to transfer in addition to their other responsibilities.

… we’ve got an ambulance that’s not taking this person, this person’s behaviour is escalating, we’ve already tried some IM [intramuscular injection], sedative. So what now? So then and then depending on how busy the department is as well … (P05)

Thinking about change

Despite the challenges of coordinating care for rural consumers presenting with acute mental health issues, participants were able to voice what they perceived needed to be improved.

Addressing stigma: Participants could reflect on stigmatising attitudes they had encountered or held as nurses towards consumers with mental illness.

… they’re kind of just put in as time wasters … they are sometimes a problematic group because you have to give them a lot of attention … but if you have a cardiac arrest in, that’s also a problematic group … (P04)

… one hand you’re thinking ‘this is self-inflicted’, and especially if it’s because of taking drugs. And then you’ve got someone who is really sick from a medical issue and you think ‘they can’t help it’. (P10)

The humanness of mental illness resonated with some participants.

I see mental health as something that affects all of us. (P02)

… sometimes they’re not very pleasant but they’re sick … sometimes they’ve been their choices in many ways … but others have had no choice and it’s just life unfortunately. (P05)

More education and support: When asked to reflect on what needed to occur to improve the management of mental health in rural emergency care, the majority of participants indicated the need for emergency mental health education for nurses working in rural EDs and UCCs. Suggestions for content included mental health triage, mental health legislation, psychiatric medication and identifying triggers. Interactive and scenario-based education were the preferred modalities of delivery. Study days were infrequent, sometimes requiring travel to regional or metropolitan centres.

… more practical training in an emergency department on … scenarios I guess would be of benefit because you don’t really know unless you’re put under the situation … (P06)

… doing mental health triage, I think when someone comes in, how do we triage someone with a mental health problem or issue? (P11)

Upskilling in mental health was considered imperative for rural emergency nursing practice.

I don’t want to be a mental health nurse but I want to be a good emergency nurse and you need to do it all. (P03)

Nurses indicated the need for closer collaborations with the community mental health team and the need for an after-hours onsite service.

… sometimes it would be good if we could like have perhaps the mental health team come over and introduce themselves … perhaps even go through some scenarios … (P12)

... having a local person on call for emergencies … you could just ring them … (P03)

Some participants identified the need for more rural mental health facilities and funding.

… if there’s nowhere for people to go you feel a bit lost for them because they’ve got these issues, not everyone understands or is tolerant of mental health issues … (P09)

… More rural health facilities for mental health treatment. You know, even like an overnight crisis mental health facility would be perfect … (P13)

Discussion

This study describes the experience and challenges encountered by a cohort of rural generalist nurses when managing emergency mental health presentations. The perception of lacking confidence, knowledge and skills in caring for mental health consumers was a key finding, resonating with other Australian research reporting on nurses1,5-7. Regardless of perceived incompetency, the theme ‘doing our best to provide care’ affirms nurses as altruistic healthcare professionals seeking to deliver safe care to consumers21. Obstructions to altruistic practice, such as a high workload, which prevents the establishment of a therapeutic relationship21, can often become a source of frustration in addition to managing competing demands8.

The paucity of mental health education for rural nurses is supported by this study. Targeted education delivered locally and frequently is preferable. It is surmised that nurses who receive ongoing mental health training will become more competent in providing mental health consumers with safe care5. Evaluations of single mental health education interventions report an improvement in the mental health knowledge and skills of participants11-15. Often the follow up of single mental health interventions does not exceed 6 months, making it difficult to report on the longevity of skills maintenance. Training may also address stigmatising attitudes towards mental illness, which has implications for the treatment of consumers6,11.

Fostering closer collaborative and mentoring partnerships with community mental health teams is an additional strategy to improve nurse competencies and the provision of care. Nurses value the skills of mental health clinicians, relying heavily on their input in coordinating the care of mental health consumers22. Undertaking a short placement in a mental health setting could also provide generalist nurses with an opportunity to build rapport with mental health clinicians as explored elsewhere in the literature14. Coordination of care and access to specialist services continues to be problematic for rural mental health consumers. Telehealth service models have met the need for improving access to mental health specialist services in some Australian contexts9,10,23. However, the rollout and modality of telehealth services (use of telephone vs videoconference) has varied across health services. Advantages and disadvantages of telehealth are well documented across a range of contexts and specialities, with a reported increase in utilisation by hospitals10,23,24. Consumer evaluation of mental health telephone services in Australia has been sparse, with few studies reporting on consumer satisfaction23,25. Findings from the present study suggest that nurses perceive that the level of care delivered by a telephone triage service does not equate to that delivered by a local mental health clinician. Whether telephone triage meets the needs of mental health consumers is beyond the scope of this project. However, it is well documented that the presence of trained mental health staff in metropolitan emergency departments is valued by mental health consumers2,26, can improve staff education16 and provide consumers with a higher level of care26.

Limitations

The sample size of this study was subject to the response of nurses to the study invitation. Novice nurses were not adequately captured. Capturing the perspective of novice nurses would be valuable in determining the effectiveness of undergraduate mental health training in preparation for rural generalist practice5. Subsequent studies should consider sampling participants from other IOR areas that utilise telephone triage or other telehealth modalities during and after hours to compare themes.

Conclusions

Generalist nurses working in rural EDs and UCCs encounter multiple challenges in providing care to mental health consumers. After hours is particularly problematic with limited onsite support from community mental health teams and reliance on telephone triage. Generalist nurses report being ill- equipped to provide care and value the input of local teams in coordinating care for mental health consumers. Targeted education and closer collaborative partnerships are required with community mental health clinicians. The delivery of mental health care to rural consumers through telephone triage services also requires evaluation to determine consumer satisfaction and safety.