Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of mental health problems in Australia are increasing1. In rural and remote areas, although mental health difficulties occur at approximately the same rate as they do in metropolitan settings, access to timely and effective services is much poorer. Therefore, the course and consequences of mental health problems can be expected to be worse in rural and remote locations. Although psychologists play a key role in the treatment of mental health problems, there is a shortage of psychologists in rural and remote locations2.

Facilitating placements in rural and remote locations for psychology students during their training is one way of both increasing current psychological services and encouraging students to work outside metropolitan centres after their training3. The identified value of clinical placements in rural and remote areas is well documented by students and is one factor contributing to students’ future decisions to return to work in these locations4. As psychology students’ experiences in rural communities have potential to influence their decisions to work, or not, in rural areas, clinical placements can be seen as being interrelated to addressing rural psychology workforce shortages. Mental health placements, generally, are regarded as a viable option for meeting the interrelated requirements of healthcare service provision, healthcare workforce and health professional practice-based education. As mental health service provision and rural workforce shortages involve a range of health and social care professionals, including nursing, medicine, social work, occupational therapy and psychology, rural mental health placements have the potential to address these issues.

Rural clinical placements mean different things for different reasons to people working in healthcare services and education. As rural clinical placements expose students to rural employment opportunities5-7, their value for workforce recruitment receives considerable attention8. Often with the range of disciplines involved in rural practice, opportunities for interprofessional education in rural areas are broad9. However, beyond the literature of interprofessional education, there is scope to explore the nature of placements for clinical psychology students in rural areas, particularly in relation to the learning experiences provided. Practice-based education literature provides a suitable theoretical framework to explore such experiences.

Practice-based education refers to ‘tertiary education that prepares graduates for their practice occupations, and the work, roles, identities and worlds they will inhabit in these occupations’10. Workplace readiness, socialisation, professional identity and complex professional practice are important aspects of practice-based education that underpin clinical placement. Supervised clinical placements provide students with opportunities to apply knowledge to practice11. The work environment in which the learning occurs and the interactions of the student in this environment are important influences on the development of expertise and work readiness12.

Of the health professions applying practice-based education principles to prepare students for work in mental health (such as medicine, nursing, social work and occupational therapy), psychology occupies an unusual position. Not all students graduating with a degree in psychology work, or even intend to work, as registered psychologists in health care. Accordingly, students studying the degree of psychology are not required to participate in clinical placements at an undergraduate level13. For the discipline of psychology, placements tend to be framed as an accredited requirement of postgraduate professionals’ practice14 rather than as a valuable component of practice-based education. To date, very little investigation has been undertaken into psychology students’ experience of learning during clinical placements, with even fewer studies conducted on placements in rural areas. Despite the lack of research, however, there is an anticipated positive influence on the rural psychology workforce of having placements in rural areas15. One retrospective study found support for the sustainability of an intern program in a rural location15, although more studies are required to explore the experiences of students on these placements and how they might contribute to improved attitudes towards working rurally after training completion. Another study reported supporting evidence for the link between health professional students’ satisfaction with their rural or remote placement and their intention to enter rural practice after graduating16. Encouragingly, students who were ambivalent about rural practice before their placement showed, on average, an increase in rural practice intention after their rural placement16. The limited evidence available also indicates that, based on the lived experience of psychology students on rural placements, these placements are an invaluable learning opportunity3.

Psychology training models have their origins in post-war USA, where the focus was on promoting the adoption of the ‘scientist-practitioner’ model. In Australia, this model has also been widely accepted and is currently endorsed by the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council, with education institutions complying with this model in undergraduate curricula13. Since the conception of this model, psychology has emphasised greater focus on the scientific aspects of the profession, with less attention placed on the notion of practice. This is reflected in the fourth-year undergraduate curriculum, where activities involving research are to be no less than 33%, but practical based activities are optional and must not exceed more than 10%17. Changes to the training and registration requirements for psychologists in recent years, along with a growing concern about a lack of psychologists in the workforce18, have been part of the impetus to consider different models of training for psychologists19.

In this study, the experiences of students and representatives from educational institutions and service providers were explored as part of a large multicentre, multiphase and multidiscipline project known as the Mental Health Tertiary Curriculum (MHTC) project. This project was conducted by the 11 university departments of rural health (UDRHs) with oversight from the Australian Rural Health Education Network. A key aim of the MHTC project was to investigate the profile for mental health clinical placements across rural Australia and to gain a greater understanding of students’ learning experiences with clinical placements. The design and scope of the study provided an opportunity for a more focused exploration of postgraduate psychology students’ experiences and their perspectives of rural clinical placements.

Method

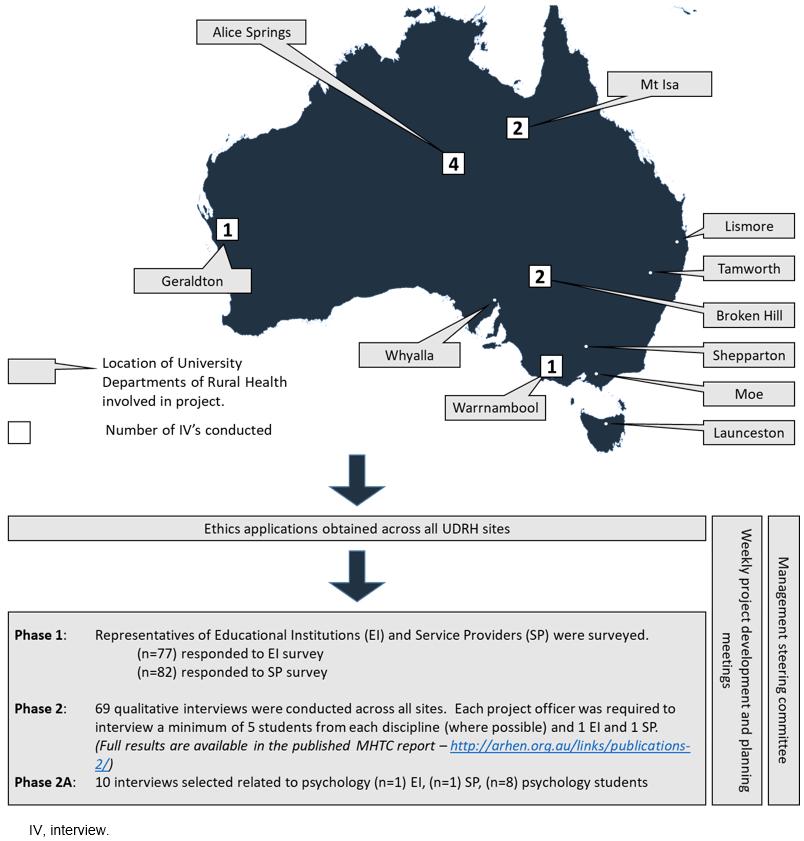

The MHTC project was undertaken in two separate phases. An overview of the MHTC project, including the location of this study within the larger project, is shown in Figure 1. In phase 1, representatives of educational institutions and service providers were surveyed to examine the number and type of health disciplines offering rural mental health placements, including the duration and settings of placements. Phase 2 provided greater understanding of the experiences from students and those representing educational institutions and service providers within these settings. Purposive sampling was undertaken to ensure representation from a range of disciplines, including psychology. For the geographical distribution of participants, see Figure 1.

In phase 2A the subset of interviews related to the discipline of psychology were explored in more detail, that is, interviews from eight postgraduate psychology students, one representative of an education institution and one service provider.

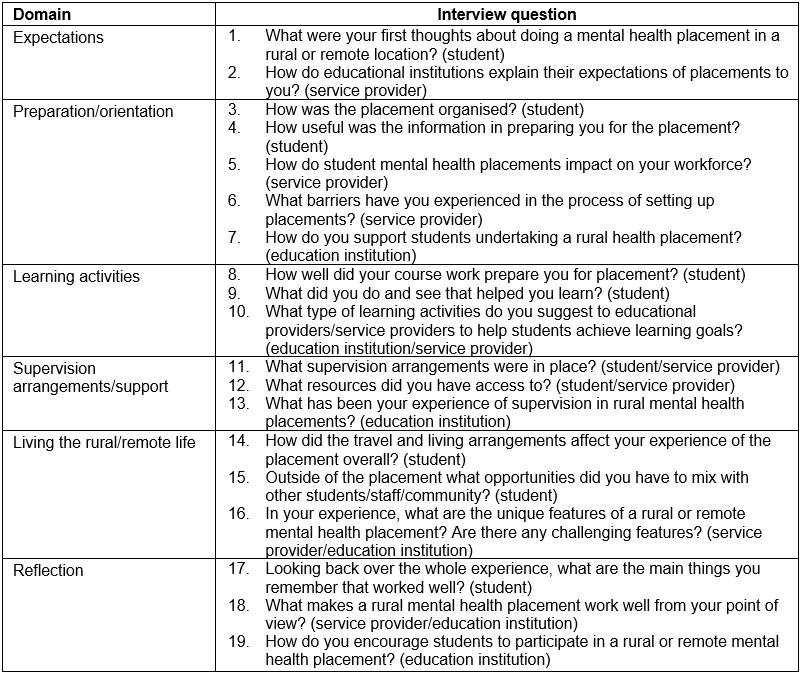

Participants for the study were sourced through the relationships with educational institutions and service providers established in phase 1. Questions to students, and individuals representing education institutions and service providers, followed a structured proforma (Table 1). Additional questions for clarification and probing were used.

The interviews were audio-recorded then transcribed by an independent professional transcriber. The accuracy of all transcripts was checked against the audio recordings. Interpretation of themes was consistent with Braun and Clarke’s notions of thematic analysis which included becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes and naming themes20. Underpinning this interpretation were principles of Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics, involving ongoing iterative dialogue with the data (hermeneutic circle, and dialogue of questions and answers) until sense-making was complete (fusion of horizons)21. Two overarching conceptual themes were identified.

Table 1: Interview proforma

Figure 1: Overview of the Mental Health Tertiary Curriculum project: psychology placement study.

Figure 1: Overview of the Mental Health Tertiary Curriculum project: psychology placement study.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from 11 human research ethics committees from educational institutions and health care services across Australia due to the spread of research sites. A total of 20 applications were approved between all UDRHs based on the initial approval of the ethics application submitted by the University of Melbourne (ethics approval number 1237923).

Results

Two key themes framed the complexity and value of clinical psychology placements in rural and remote areas.

‘Beyond expectations, but …’

The value of clinical placements being ‘beyond expectations’ for students is tempered by challenges related to implementing and sustaining the placements. These two ideas exist within this theme to demonstrate the tenuous nature of placements in terms of the contrast between the aspects of placement that students appreciated and the difficulties they faced to enable them to occur.

Students described their expectations in terms of their learning experiences as being more substantial than they had anticipated or previously known.

I really enjoyed it, more than I ever thought I would. I think it’s a combination of it’s pretty down to earth in the country and a lot of variety. (Student 22)

Their expectations for diversity in clinical presentations were also exceeded. In addition the range of clinical skills required, accompanied by increased responsibility, was consistently reported. Students also felt that they were able to consolidate their learning into practice more than they had expected and that learning was often interprofessional in nature.

The diversity and breadth of opportunities to work collaboratively were appreciated by the students.

Being able to do work that you probably wouldn’t do elsewhere, so be much more involved, having a much wider opportunity to work with people of all different presentations. (Student 13)

High regard was given for variety in the type of presentations seen. The range of clinical interventions used to care for clients revealed different ways of working that added depth to students’ experiences.

I think this community health placement will end up being the highlight of the degree because of the wealth of experience that you get and exposure to so many different clients and different approaches. (Student 68)

Students acknowledged that rural mental health placements had distinct features, identifying that a level of adaptability was required to care for people in rural locations.

I asked who I’d be seeing and she kind of said everything, it’s very different out there … you’ve got to be very flexible in how you practice. (Student 3)

When you come here you realise that mental health is different and the skills that I am using at the moment are a lot of the information I got during the course. So the applicability of it really hit home. (Student 50)

While acknowledging value, the theme of ‘Beyond expectations, but …’ introduces a sense of tenuousness. Expectations of requirements to access and support clinical student placements contrasted with the benefits students described. Nearly all students stated that the placements in rural areas were self-initiated and regarded as optional by their supporting university. Difficulty accessing appropriately qualified supervisors was also perceived as a barrier to participating in rural clinical placements. Decreased availability of supervisors who reside in rural locations posed challenges, with higher reliance on technology to provide remote support to students. Restrictions on the number of hours that can be provided using this method were regarded as problematic.

There aren’t that many supervisors. So there’s a shortfall of supervisors and there are quite a lot of people who are in remote areas, working without high levels of supervised experience. The other problem that makes that harder is that the regulations are that there’s a certain amount of face-to-face supervision. So it’s not enough just to say that you’ll do it all via email or via telephone. (Service provider 4)

In addition, the legislative requirements from the governing body that regulates the supervision of psychology students create challenges for those who are willing to provide supervision.

For psychology, we certainly have a lot of barriers … the supervisor has to go through a lot of hoops before they can supervise a student … they are doing it for free and that makes it hard for them to put up their hand and volunteer their time. That minimises the pool that we can select people from. (Education institution 25)

Concern was expressed for the future availability of supervisors with the impact of professional obligations affecting further accessibility to clinical placements in rural areas.

It’s becoming a lot more rigorous in terms of the requirements for supervisors and it’s going to put incredible pressure on the system generally. (Student 68)

‘Immersed in connectedness with …’

‘Immersed in connectedness with …’ conveys the importance of relationships, particularly with respect to the domains of rural community, other professions and to the students’ chosen profession of psychology. Connectedness with these domains enhanced their development of professional identity and immersed them in the interrelationship between community and practice in rural areas. There are three subthemes in this category.

Connectedness to community: Students identified that their rural placement involved more than the application of clinical skills. It involved becoming engaged with the community and adapting to the rural way of life.

I guess working in small communities you become part of the community if that makes sense ... it’s like having extended family. (Student 33)

Recognition of the aspects of poorer health outcomes in small rural locations and reduced access to services were highlighted by students as being more prevalent. Students recognised that the reduced population within these communities promoted a ‘sense of familiarity’ between relationships and impacted on how people related to one another.

I guess seeing the impact of isolation on mental health … I think it exacerbates mental health a bit more … out here it’s that [depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and personality disorders] but greater severity … it’s a small community so everyone knows everyone. You’re given much more information than you would elsewhere. (Student 13)

Particular challenges for students becoming immersed in the rural way of life involved the ability to maintain professional boundaries and deal with feelings associated with stigma.

It is really hard ... closer networks and the chance of seeing clients. You’ve just got to remove yourself or talk about or manage it … it can be very awkward and there’s potential to breach confidentiality. (Student 13)

Connectedness to other professions: In some situations, mentorship was provided by other health disciplines. Students said this enhanced their understanding of other professions’ roles. Observing different approaches to care were regarded as beneficial.

I think what I’ve really enjoyed is working with the other people out here on the team … the speech pathologist, the OT [occupational therapist], the physio. Working with them and shadowing them as well, see what kind of work they do. (Student 33)

Just being able to feel part of a team is extremely beneficial for a placement like that, especially if you’re just plonked there straight out of coursework. (Student 54)

Feeling valued by other rural health professionals and providing a worthwhile contribution to client care were acknowledged by students. This was particularly important when it was identified that limited access to different professional disciplines, such as psychology, occurred within the treatment team in rural areas. Students felt this added to their worth from an interprofessional perspective.

It’s kind of understanding that in the rural setting, what access people have to services and it’s just more restricted as compared to metropolitan … the value of the rural placement may be about the value placed on the student because resources are so tight … it gives a sense of inclusiveness and purpose, of being part of the team. (Student 68)

It was really good working with mental health nurses and the psychiatrists and experiencing the multidisciplinary approach … I didn’t realise how often that they would have to liaise with the police and … all the other services. (Student 22)

Students felt their contribution was not only about their ability to work within an interprofessional group but how relationships with other health professionals facilitated constructive input. Reciprocation of knowledge between professions occurred through a mutual willingness to exchange information. Students felt their contribution had value in alleviating demands on workloads.

The team was good, there was a lot of variety … I just learned so much … it adds something to the teams … I got to write basic reports and it just took some of the pressure off when they were under the pump a fair bit … you feel like you’re useful as well. It wasn’t just me learning and them not getting anything in return … I started to feel like I was a functioning team member. (Student 39)

Connectedness to profession: The hands-on experience gained while on a rural clinical placement highlighted the integration of knowledge into practice. Recognition was given to the way knowledge brought to the placement built further depth of understanding and how this then shaped psychology practice.

There’s some things, not until you get there that you really sort of get a good experience of it. That knowledge becomes properly assimilated. (Student 68)

The difference between academic learning and ‘real life’ learning was identified. Exposure to complex presentations provided insights into the scope for psychology practice and contributed to the grounding of theoretical knowledge. In addition, students reported a desire to have greater access to real clinical scenarios on the basis that it increased preparation for practice.

I don’t think anything can prepare you [for seeing severe psychiatric disorders] … maybe psychologists could be a bit like medical students where you go on rounds in an inpatient unit, it might get you a little bit more prepared, but that’s more experiential again, it’s not academic learning. (Student 39)

Discussion

For psychology students in this research, clinical placements in rural and remote areas provided valuable opportunities to engage with their own profession, health professionals from other disciplines and the broader community. Students reported feeling valued and also feeling connected to the community within which they completed their placements. These kinds of experience are extremely important in terms of developing positive attitudes towards working remotely. Experiences such as creating a sense of connection with your community are extremely difficult to provide in a metropolitan placement.

Through these rural placements, students developed their professional roles and identity and participated in collaborative health care. Wenger’s notion of situated learning provides a theoretical basis to conceptualise such learning22. Relevant to practice-based education for collaborative health care, situated learning highlights the importance of students learning through participating in practice and collaborating with others23.

In highlighting the value of clinical placements for psychology students, the findings of this MHTC project support the findings of other studies. For example, Webster et al examined nursing students’ perspectives of rural placements and found that students reported broad exposure to clinical scenarios, interaction with other health professionals and awareness of community as factors contributing to a positive learning experience24. A further study relating to nursing students’ rural clinical placement identified increased competence, self-assurance and organisational skills when compared with metropolitan students’ experiences of placements25. Similarly, the connectedness theme aligns with other studies relating to health professions’ placement experiences beyond rural areas. Levett-Jones and Lathlean identify ‘belongingness’ as integral to the quality of learning achieved by students while on placement and is an essential foundational component to achieving clinical capability26. Interprofessional engagement as identified in the theme ‘Immersed in connectedness with’ is highlighted in the literature relating to clinical placements. Brown et al examined the perspectives of students of paramedicine, midwifery, radiography, occupational therapy and pharmacy, and identified interprofessional collaboration as enhancing learning27.

A key implication relates to the role of practice-based education for the psychology profession. In common with other disciplines, the socialisation and development of professional identity are valued aspects of becoming a health professional. Students’ socialisation into their professional roles begins when the novice practitioner starts to identify with the culture of their profession and develops their own internalised professional values and norms. Professional identity is fundamentally linked to a person’s development of self, how they engage with the environment they work in and how they mature through the experiences they encounter28. Most health professions begin the process of socialisation by incorporating clinical placements early in their learning29-31. Placement is explicitly valued by other health professionals. This leads to scope for further discussion within the psychology profession relating to the value of clinical placements and the timing of placements for socialisation and the development of professional identity. These ideas are reflected in current discussions about different training models in psychology19.

The incorporation of clinical placements into current psychology curriculum requires careful consideration of a range of benefits and barriers. The findings of this research into rural clinical placements highlight some of the benefits; however, the barriers are complex. One key barrier relates to psychology being a basic degree preparing people for work in a variety of different areas. A strong argument could be made for early streaming of those who seek to work clinically after graduation. Such streaming would provide opportunities to begin socialisation and the development of a professional identity earlier than is currently occurring. However, this goal needs to be tempered with consideration of higher education institutions’ constraints relating to financial viability, course numbers and changes to undergraduate curriculum for psychology.

Another barrier to widening the use of clinical placements relates to the recent changes in legislation by the Psychology Board of Australia. These changes have placed stricter conditions on accreditation and training requirements for psychology supervisors32. The impact of this legislation on implementing and sustaining adequate clinical placements and supervisors requires careful attention. Consideration of these implications is particularly relevant for rural areas. Responding to potential increased interest in these areas, the demand for clinical placements needs to be undertaken with sensitivity to competing requirements for service provision and workforce issues. Integral to developing successful clinical placements is collaboration between accrediting organisations and universities. Such collaboration can promote clinical placement opportunities in rural areas and identify strategies to facilitate appropriate supervision.

Another implication for the findings of this research relates to rural workforce shortages. As mentioned in the introduction, rural placements can be an important strategy for addressing workforce shortages. The data provided by this small number of students provide further support for the value of rural clinical placements to address workforce shortages both currently and into the future. Although trainee psychologists work under supervision they are still able to provide timely and effective services in places where there are workforce shortages. There is, then, an increased possibility that, after a positive rural placement, the psychologist is more likely to consider working in a rural setting.

The current study, therefore, makes additional contributions to the small body of literature demonstrating the value of rural clinical placements during the training of psychologists. It is important to highlight that these experiences appear to be consistent with the experiences of other health professional students reported in the literature16. With new accreditation guidelines affording increased flexibility for remote supervision during placements, rural placements are becoming increasingly viable33. It would be timely for higher education providers to demonstrate tangible interest in addressing the rural psychology workforce issues by promoting placements in rural and remote contexts. Ultimately, it may even be ideal for rural placements to become a mandatory training requirement.

Study limitations

A limitation of this study is that the findings are part of a larger project, which was not conducted specifically to examine the nature of psychology students’ perceptions of clinical placements. As a result, key demographic data relating to the participant sample were unable to be obtained retrospectively. The sampling of students for the initial study was purposive and, as a result, all students participating in the study had undertaken a placement supported by a UDRH, which may have had an influence on the generally positive responses given by students. This may be due to the level of practical support (ie accommodation) and emotional support provided by the UDRHs. While information about motivation for undertaking a placement in a rural location was not specifically investigated, a number of the psychology students within this study indicated their placement was self-initiated. An increase in the availability of rural placements would provide the opportunity to conduct further research to develop a fuller understanding of the benefits of these placements to the education of psychologists and to rural mental health services more broadly.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the value of rural clinical psychology placements. Beyond highlighting this value, however, scope was identified for further discussion within the psychology profession. This is needed to explore the benefits of effective student clinical placements in rural locations and their contribution to practice-based education and work readiness. In doing so, there is the potential for psychology to join the ongoing dialogue of other professions regarding practice-based education for health professional practice. This is particularly important for sharing the solutions to challenges regarding the ongoing development of clinical placements in rural areas. Outcomes of such discussions and dialogue have implications for maximising the value of clinical placements in rural areas and their impact on work readiness and workforce distribution.

Acknowledgements

The research findings in this article were supported by the Australian Rural Health Network (Australian Rural Health Education Network) and include the work conducted by the Management Steering Committee and Project Officers from the MHTC project.

References

You might also be interested in:

2008 - Forty years of allocated seats for Sami medical students - has preferential admission worked?