Introduction

Indigenous children are among the most vulnerable groups in Canadian society. Section 35(2) of the Constitution Act 1982 recognizes three groups of Indigenous peoples in Canada: Indian, Inuit, and Métis. The term Indigenous will be used in this article when making a general reference to the three groups; however, First Nation will be used to refer to Indigenous people who live on a reserve. Concern for the health of Indigenous children in Canada was highlighted in a UN report, which suggested that social conditions are leading to poor health outcomes1. One of these health outcomes, diabetes, has been linked to childhood obesity2. Childhood obesity is of concern in both the Indigenous population and the broader Canadian population; however, the prevalence of obesity is much higher within the Indigenous population3. Physical activity is important not only for overall wellbeing but also for energy expenditure and maintaining a healthy weight. Research shows that many Indigenous children are physically inactive3,4 and are not meeting the daily recommendations for physical activity5,6. Therefore, it is important to understand what influences physical activity in this vulnerable group. This study draws from a socioecological approach7 and focus groups with caregivers in six rural First Nation communities (reserves) to identify determinants of physical activity among Indigenous children.

Obesity, physical activity and Indigenous children

In the 2016 Canadian census, 1 673 785 people self-identified as Indigenous, representing 4.9% of the total Canadian population8. Indigenous people represented the fastest growing population in Canada, as well as the youngest8. Over one quarter (28%) of the Indigenous population were children aged 14 years and under, while non-Indigenous children represented only 16.6% of the total non-Indigenous population8. The prevalence of obesity in Indigenous children in Canada is much higher than in the general population3. The rate of obesity among Indigenous children and youth living off-reserve was high (34.5%) in comparison to the rest of the population (26.1%)3. Results from the First Nations Regional Health Survey, which surveyed 216 First Nation communities, found that the rate of overweight and obesity was 62.5% among Indigenous children aged 2-11 years (parent-reported) and 43% among Indigenous youth aged 12-17 years (self-reported) living on-reserve4. Obesity in childhood is of concern because of the increased risk of developing health conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome9. Thus, childhood obesity in both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population is a significant health issue in Canada.

One of the ways to combat this epidemic is through increasing physical activity10. Physical activity has been defined as 'any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure'11 and involves energy expenditure in both organized, purposeful exercise and non-exercise activity12. Low levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour have been linked to overweight and obesity among children in Canada10. The Canadian Health Measures Survey found that 'only 7% of children and youth are meeting Canada's guidelines of 60 minutes of physical activity a day'13. The same study also found that the average amount of sedentary time for children and youth was 8.6 hours per day13. Another indicator of sedentary behaviour is measured in screen time. A study of Canadian youth in grades 6 to 12 found that 50.9% reported spending more than 2 hours per day using a screen based device and the average daily time was 7.8 hours (±2.3 hours)14. Canadian guidelines recommend limiting screen time to no more than 2 hours per day for children and youth15.

Physical activity levels among Indigenous children and youth are also of concern. Self reported physical activity levels among Indigenous youth (aged 12-17 years) living off-reserve found that the mean energy expenditure was less than 6.3 kJ/day (1.5 kcal/day) and they were categorized as 'physically inactive'3. Self-reported physical activity levels among Indigenous youth living on-reserve (ages 12-17 years) indicate that 49.3% were physically active, 22.6% were moderately active and 28.1% were inactive4. Both of these studies relied on self-reported data, which are less reliable than direct measurement. Direct measures of physical activity using pedometers have shown that 36-59% of Indigenous children are not meeting the daily recommendations for steps5,16. Physical inactivity among Indigenous children and youth are of particular concern because it is a risk factor for developing obesity related conditions17,18.

Colonialism as a determinant of health

Obesity is influenced by a complex interplay between genetics and physiology19,20 as well as the social environment17. The social environment includes aspects such as income, education, early childhood development, and food insecurity also referred to as the social determinants of health21,22. First Nation communities lag behind non-Indigenous communities on determinants such as income, education, housing, labour force activity, health care, welfare, and social services23. This lag has been attributed to Canada's legal, institutional, and policy framework such as the Indian Act and residential schools24.

In addition to the determinants of health identified by Wilkinson and Marmot22, determinants that are unique to Indigenous peoples in Canada include colonial legislation and policies like the Indian Act and residential schools; loss of land through treaties; and inadequate funding for water treatment systems, housing, health care, and education in First Nation communities24-26. Recently, colonialism has been identified as the key determinant of Indigenous health in Canada27. The Indian Act, which was first passed in 1876, dictated almost every aspect of First Nations peoples' lives. Significant instruments of colonialism were residential schools, which were operated by churches between the 1800s and 1990s. Indigenous children were often malnourished in these schools28 and some students were subjected to nutrition experiments even when they were clearly malnourished29. Many Indigenous peoples are still coping with the effects of colonialism and its intergenerational impact on health status28,30. Studies have shown the negative effect of colonialism on diabetes management, including food choices and physical activity, in First Nation communities31,32. Food insecurity also influences dietary choices and has been linked to access, availability and affordability of good quality food in First Nation communities33.

Much research on Indigenous peoples' health has been conducted from a biomedical perspective; however, more recent research is increasingly acknowledging that social determinants have a significant impact on health outcomes for Indigenous peoples6,34,35. Understanding the social determinants, including the effects of colonialism, that influence physical activity in Indigenous communities is important in addressing obesity among Indigenous people36. Because children are particularly vulnerable to disturbances in their health during their developmental years, identifying the determinants that affect this population is important as these can set a trajectory for their health in the long term17. The purpose of this research was to identify the determinants that influence physical activity among Indigenous children as perceived by their caregivers in six First Nation communities in north-eastern Ontario, Canada.

Socioecological framework

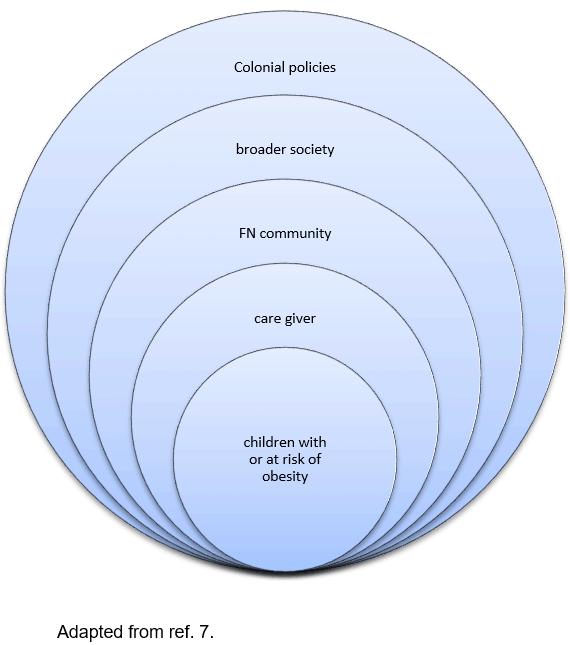

This research was based on a socioecological framework in order to develop an understanding of determinants of physical activity among Indigenous children. Egger and Swinburn37 proposed an ecological approach to understanding obesity by recognizing biological, behavioural and environmental influences. Loppie Reading and Wien34 developed a life course approach to understanding health inequalities among Indigenous peoples that includes proximal, intermediate, and distal determinants of health. Similar to the life course model is the socioecological model proposed by Willows et al7 to understand obesity among Indigenous children in Canada. This framework considers interrelationships among individuals, families, the community environment, and societal level determinants that influence physical activity and nutrition. A socioecological framework also includes factors such as colonization, dispossession of lands, and assimilation policies that influence all levels within the framework. This framework was important to explain how social and ecological determinants influence physical activity among Indigenous children in the present study and the barriers that need to be addressed to increase physical activity.

Methods

A community-based participatory research approach was used in this study, beginning with a community engagement process with six First Nations conducted by the lead author. These First Nations were invited to participate because they were located in the study area of Northern Ontario, had identified childhood obesity as a concern, and the lead author had an established research relationship. In the initial stages, information meetings about the project were held within each community. A steering committee comprising representatives from each of the participating communities guided the lead researcher on the research questions and methodology. The lead researcher worked closely with educators and health staff in each of the communities and tailored the data collection for each community.

Data collection

In this phase of the study, qualitative data were collected during focus groups with caregivers. Participants were recruited through letters of information and posters in each community. Focus group participants consisted of Indigenous parents or grandparents and interested community members. All focus groups were conducted in English and facilitated by the lead author. The focus groups were conducted at First Nations community health centers and schools. Written consent to participate and oral consent for audio-recording were obtained prior to the start of the focus groups. Semi-structured and open-ended questions focused on exploring how physical activity has changed in families and communities. The focus groups lasted between 90 and 120 minutes. A total of 33 caregivers(27 females, 6 males) participated in one of eight focus groups. Most participants were parents of children aged 11-14 years. In two of the focus groups the grandparents were male and female and in one focus group the grandparent was female.

Analysis

The lead author is Indigenous and a member of one of the participating communities, thus giving her both an insider perspective and attendant biases. Because of her personal, professional, and educational background she has a dual perspective, or what Albert Marshall describes as, 'two-eyed seeing'38, which in this situation means having an understanding of both an Anishinaabe (Ojibway) worldview and a Western worldview. The other members of this research team also contribute to the dual lens of two-eyed seeing, each bringing their own understanding of Western and Indigenous knowledge systems.

Audio-recordings from the focus groups were transcribed and participants were given pseudonyms. The transcripts were imported into the qualitative data software program NVivo v10 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com) and a thematic analysis was conducted. The transcripts were reviewed for both manifest content (visible, surface level content) and latent content (underlying meanings) according to the content analysis approach described by Babbie39. Segments of data were coded with a label that categorized and summarized the data40. The codes were initially derived from the data as perceived by the lead author with a dual perspective as an insider who is a member of one of the First Nation communities and an academic. After all the transcripts had been coded, the categories were reviewed and some were collapsed. All of authors then reviewed the resulting preliminary categories and suggested a second review of the data, which resulted in the addition of new categories. Categories were reviewed by the research team until all concerns were resolved.

After a preliminary report on the key findings was complete, the results were shared with participants to verify the interpretation and relevance to the participating communities. Two member-checking sessions were held with selected participants from the initial focus groups to validate the findings and to solicit insight into the findings. Participants were invited from the original focus groups,, with a total of four participants in one session and five in the other session. Four of the six communities were represented in these sessions.

Ethics approval

The research team is familiar with chapter 9 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans: 'Research involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada'. Furthermore, ethics approval was obtained from the Manitoulin Anishinaabek Research Review Committee and from the Laurentian University Research Ethics Board (REB# 2012-05-12). Community consent for this study was granted by all six First Nation band councils.

Results

The discussions during the focus groups were rich with insights about factors that influence Indigenous children's physical activity from the caregivers' perspectives. Participants noted that current patterns of physical activity have been shaped by recent significant lifestyle changes that manifest themselves particularly in outside play, walking and chores. Further analysis of the focus groups found that physical activity is determined by recreational technology, safety concerns, and the impact of colonial legacy on community sports and recreation programs.

Recent lifestyle changes

Playing outside: A common theme when discussing physical activity in the past was that participants recalled being sent outside to play for long periods of time when they were children, only going home for meals or when it got dark. While children were outside they would look for other children to play with or they would congregate at a previously agreed upon location like a baseball field. Participants characterized their play as being imaginative because they created games and activities based on what was available in their environment.

We played outside. We went swimming, we went running, we played Indian ball, we climbed trees, we you know, we made up our own stuff like, our own tree houses, we would do things. (Aangeniinhs)

An important element to outside play in the past was that there was little adult supervision; however, the participants noted that as children they watched out for each other. In contrast, participants reported that it was difficult to get their children to play outside and the most common reason given was that technology was replacing outdoor play and activities. One parent described her son's typical behaviour

Like [the boys] hang out and stuff but that's just usually YouTube and video games, electronic stuff. You wouldn't actually find [my son] down the road or whatever, kind of walking around on his own, just being adventurous. (Maani)

Walking: Walking was another frequently mentioned form of past physical activity. Participants recalled walking long distances within their communities to play at a friend's place or for activities like swimming. One participant recalled that because her family did not have a vehicle, walking was the only way for her to get around when she was a child:

I remember, when I was growing up, we didn't have a vehicle. We had to walk everywhere. I remember my friend used to live a mile away and I would walk a mile just to go play with them. We were taught 'go out and play' so we would walk a mile. (Pichi)

Participants reported that in the past there were fewer vehicles in the communities and that, even if there was a family vehicle, their parents would likely not have been inclined to drive their children around. In contrast, in the present day, participants reported that their children expect to be driven around their community even for short distances and parents tend to accommodate them.

Nowadays it's not a problem for kids to ask 'can you give me a ride down to here?' It's like 'Really? We used to walk there. It was not a problem.' 'Oh, it's so far.' 'Jeepers you kids!' (Ziibiinhs)

In one community, possibly because of the distance between subdivisions within the community, participants reported that they observe youths hitchhiking within the community for long periods of time when they could have reached their destination in less time had they walked.

Chores: Participants recalled that as children they were expected to do physically demanding chores as part of their daily activities. The standard of living was quite different than it is today and some homes did not have running water or electricity. In some instances, chores such as splitting wood or hauling water were necessary for their family's survival:

Well, we had to work. In my time, we had to bring some dry wood and get the water. We didn't have the luxury of you got, like we got, we got hydro. We didn't even have hydro. We didn't have running water. We had pumps. Yeah, we had to do our chores. Bring the wood in, chopping the wood, getting water over there and there was about seven of us in my family. We had to do our share. (Wiiyam)

In the past, because household chores were physically demanding children became more physically fit simply by completing them. As housing conditions have improved, physically demanding chores that were essential to the functioning of a household in the past have diminished. Some participants reported that their children were still expected to do chores; however, these chores tend to be less labour intensive compared to those in the past. One participant compared the difference in level of work:

When we were growing up we would get the water from the well, bring it in and heat it up then do the dishes. [nowadays, my son] He has to fill the dishwasher, you know? (Pichi)

Chores are still important in these households, but the level of physical activity required to complete them has decreased.

Technology

Technology was a common theme when participants were asked what has brought about changes in physical activity among children. Participants recalled that when they were younger there were only two channels on television and one telephone in their home. In contrast, participants reported that the pervasiveness of newer forms of technology like computers, video game systems and tablets keeps children indoors and sedentary for hours at a time. The link between technology and sedentary behaviour is described by one participant:

It's all the new technology that they don't get out - well most kids, I can't say all because there are some who still enjoy going out. But I can speak for my kids - they're wrapped up in the technology. They'll sit and play on their iPads or the computer. It can be a beautiful day out and they'd be sitting there. 'Get outside and do something!' 'Ah, just a minute' 'Okay, it's two hours later and you're still sitting in the same spot! Holy!' (Ziibiinhs)

Participants suggested that there has been a proliferation of electronic devices used by children and they identified material scarcity when they were growing up as a reason they indulge their children with electronic devices:

I think mothers, parents, as parents, we spoil our kids rotten. We buy them all these stuff. All these electronics and they don't go out. They are sitting at the TV. They're playing their games. (Zaben)

While the increased use of electronic devices is not unique to Indigenous children, among Indigenous caregivers it is often perceived as a parental response to scarcity experienced during their childhood. This in turn compels some parents to 'spoil' their children with electronic devices.

Safety concerns

Caregivers were aware of the importance of physical activity and the negative impact of extended screen time; however, during discussions it became clear that they were ambivalent about outdoor activity. In fact, many preferred children to be engaged in indoor activities over outdoor activities because of safety concerns when their children were unsupervised. Four subthemes emerged as safety concerns: perceived danger from animals such as stray dogs and bears in the community, exposure to drugs and alcohol and to people under the influence of drugs and alcohol, fear of unsupervised play being reported to child protection agencies, and fear of children being at risk for assault or abduction.

Danger from animals: Concerns about dogs running at large and wildlife such as bears were some of the reasons given for allowing children to stay indoors:

But fear, too, is another thing. There's a lot of stray dogs. Both myself and my daughter have this awful fear of dogs. I know it keeps me housebound unless I'm with my husband, then I'm fine. My daughter won't walk anywhere because of all the stray dogs. (Manyaan)

Many First Nation communities struggle with controlling their dog population - so much so that it can be a public health and safety issue41. These fears are not unfounded, with reports of injuries and fatalities from dog attacks in First Nation communities42. In addition to dogs running at large, some participants were concerned that children may encounter bears. Keeping children indoors and safely away from dogs and wildlife has become an approach to keeping children safe, resulting in indoor sedentary activities.

Exposure to drugs and alcohol: Fears that children may meet up with impaired drivers or people walking around who are impaired from drugs or alcohol was another safety concern expressed by participants:

Then you worry about the drugs. People acting out on drugs. You never know if your kid is going to meet up with someone who's totally high on something that doesn't know what they're doing or whatever. (Zhanii)

A related concern about drugs and alcohol was about preventing children from getting involved in drugs or alcohol by keeping them at home and under their supervision:

They settle into their routines of video games which on one hand is a good thing because they're not out running the roads. They're not going to be involved in drinking because they're at home. We know where they are. (Aan)

Higher rates of addictions are one of the many consequences of the colonial history and the related multigenerational trauma manifested in many Indigenous communities43,44. The impact is not only on those who live with addictions, but also on the children in the community as caregivers, explained in this research. Keeping their children safe from impaired drivers, encountering people who were impaired and preventing children from drinking alcohol and taking drugs emerged as caregiver priority, overriding concerns over physical inactivity. By keeping children inside, they would be safe from harm and from engaging in harmful behaviours, although less physically active.

Child welfare system: Participants described fears of being reported to the child welfare system if they allowed their children to play freely throughout the community because it might be perceived that their children were recklessly unsupervised.

Yeah, there's accidents that have happened along the years and I think it has made people paranoid and the fear factor and stuff like that but also the governing of, you know, 'Well, you're going to get your kids taken away.' (Aangeniinhs)

Canada has a long history of state sanctioned polices that removed Indigenous children from the care of their parents, which continues today. The current disproportionately high number of Indigenous children in the child welfare system is reminiscent of past polices like the residential school system and the 'sixties scoop', during which Indigenous children were systematically removed from their homes45. Research shows that 48% of 30 000 children and youth in foster care are Indigenous, although the Indigenous people make up only 4.3% of the Canadian population46. Thus the statistics indicate that Indigenous caregivers' fears over losing their children into the child welfare system are well founded, and many if not all of the families in participating communities have been touched by forcible removal of their children. Thus unsupervised outdoor physical activity has been curtailed by these experiences. This should be taken into consideration for physical activity promotion.

Assault: The fourth concern was keeping children safe from assault. Four of the communities in this study are transected by highways. This leaves children vulnerable to assault or abduction by people passing through the community. One participant recalled how her experience influenced what she teaches her children:

For me, living so far up there and there not being so many houses. They do get a lot of exercise. It's more of a safety thing. Because I know as a kid walking just a five-minute walk when I was a kid I'd have vehicles stopping like 'Do you want a ride?' even when I was a teenager. I'm just like, 'No, I'm just going there.' I taught them that but it's still a safety concern. (Waaskonye)

In this particular quote, the mother expressed that being offered a ride was a safety concern because of strangers driving through the community. Fear of abductions is very real for these caregivers as the high rates of murdered and missing Indigenous girls and women have reached a state of crisis and resulted in a national inquiry in Canada47. Because of this reality, many parents are highly vigilant about safety, which includes keeping their children close to home.

Impact of colonial legacy on community programming

Community sports and recreation programs were cited by many of the participants as an opportunity for their children to get physical activity. Participants noted that participation in organized sports off-reserve was expensive and transportation was a barrier. Participants reported that community recreation programs tended to be intermittent and that staffing was inconsistent as a result. Three subthemes emerged as negative impacts on community programming designed to encourage physical activity among children: low volunteerism, lack of parental support, and reliance on government.

Low volunteerism: Participants noted that volunteerism for community sports programs was low, which could result in activities not being available. One participant described the impact that low volunteerism had on community programs:

Some years the parents will step up and there will be teams. So you'll have one season where there's enough teams for the kids but the next summer - nothing. (Sapi)

Parental commitment: In addition to volunteerism, parental commitment was seen as important for the continuation of children's physical activity programs. Participants reported that at the start of a program participation rates are high but as time goes by participation declines. One parent described how this typically happens:

For organized sports, the parents take them. We had soccer here in the community and we had about four teams for the kids in the school. They started off with full teams and half dropped out or didn't show up afterwards. They stopped coming because parents [were] not driving them. Transportation is [the reason] what I'm guessing. A majority of them live way over [there]. Some parents were consistent in driving their kids so you knew which ones would show up. (Sapi)

Parental commitment was seen as necessary for programs to continue: children need their parents not only to encourage them to participate but also to provide transport to an activity.

Reliance on local First Nation government: Participants described the pervasive expectation among caregivers that the local First Nation band government was responsible for organizing community sports and recreation programs, for paying registration fees, for providing equipment, and for providing transport. The comments below reflect the frustration that participants felt when confronted with this viewpoint:

I think it's the parents' expectations that somebody is going to cover my registration cost, somebody else is going to take my child to a hockey game, you know. Stuff like that you see it and you just kind of get burned out and it turns to this negative thing. (Aangeniinhs)

While recreational programming is important for physical activity, focus group participants identified low volunteerism, lack of parental commitment and reliance on the local government/administration as factors that have a negative impact on community sports and recreation programs.

These findings were based on focus groups that took place in six First Nation communities in north-eastern Ontario. Future research will be required to examine the generalizability of these findings beyond this region. Further, the self-selection of participants in the focus groups may be have biased towards caregivers who were highly interested in children's nutrition and physical activity. Thus the voices of those who may be struggling with other issues or had other priorities were not heard.

Discussion

This research on the determinants of Indigenous children's physical activity was motivated by concern for the increasing prevalence of obesity among children in these six First Nation communities. This research was also influenced by a commentary on the childhood obesity epidemic by Whitaker48, who suggested that '… we must ask not only how our way of living has changed but why'. Further, Willows and colleagues7 issued a call for more research on understanding how obesogenic environments in Indigenous communities affect children's physical activity. For that reason, a socioecological approach was used to identify caregiver's perceptions of the determinants of children's physical activity in six First Nation communities. Participants described how physical activity has changed in their communities from their recollections of active childhoods through outside play, walking, and physically demanding chores to the much more sedentary behaviour of children. Several factors were identified that influence children's physical activity: technology, safety, and community sports and recreation programming. All factors had ties to the consequences of colonial policies and these root causes must be addressed in order to improve physical activity in the participating communities.

The emerging consequences of colonialism on physical activity

Technology at both the community level and in households has had a significant impact on children's physical activity in these First Nation communities. Community infrastructure has improved over the past 40 years with developments like three-phase electric power and community water treatment systems so that homes now have the capacity for numerous appliances, running water, and most have central heating (P. Madahbee, personal communication, 2015). As a result, children are no longer required to perform physically demanding chores that were once required to meet the basic needs of drinking water and heating. These positive developments have contributed to more sedentary behaviours, as they have elsewhere in the world.

The participating First Nation communities have improved socioeconomically between 1981 and 2011 in measures of income, education, labour force, and housing23. It is the authors' contention that improvements in labour force activity and income have allowed families with more discretionary income to purchase recreational technology like computers, video game systems, and tablets. Caregivers noted that indulging children was a response to scarcity experienced as Indigenous people in their childhoods. The proliferation of recreational technology tends to support sedentary behaviour rather than physical activity. While the use of recreational technology is likely similar to the broader Canadian society, within these communities it is compounded by caregiver's safety concerns, including a history of state sanctioned removal of children from families as well as high prevalence of violence, particularly against Indigenous girls. This fear of allowing children to be away from their home coupled with a desire to give children what the caregivers themselves did not have provides conditions in which children are allowed to be sedentary for long periods of time.

Fears about dogs and bears, drugs and alcohol, child welfare agencies, and assault led caregivers to prefer indoor activities for their children. Intergenerational trauma from colonialism has contributed to high rates of addictions in First Nation communities43; caregivers were very concerned about drug and alcohol abuse, and keeping children indoors was a response to keep them safe.

Colonial policies and practices such as residential schools and the 'sixties scoop' have also influenced parental preferences for safe, indoor activities. Although the First Nation communities in this study are served by Indigenous child welfare agencies, fears of being reported to these child welfare agencies persist as the rates of Indigenous children in foster care continue to be significantly higher than the non-Indigenous population46,49. As a result, caregivers limit outside play without supervision.

Sexual assault is a grim reality in First Nation communities, particularly against Indigenous women and girls. Indigenous women and girls have long been the target of sexual assault. This issue is of national concern50,51 and has resulted in a national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls that commenced in 2016. Children are also vulnerable to assaults within the community52. The prevalence rates of child sexual abuse among Indigenous people is higher than the rates among non-Indigenous Canadians and is estimated to be between 25% and 50%53. Limiting unsupervised outdoor play was seen as a way to keep children safe from assault.

Community programs

Caregivers identified financial barriers as a barrier to participation in sports and recreation programs off-reserve. To address this, First Nation governments have lobbied for and accessed funding for community programs. However, this funding tends to be annualized, resulting in uncertainty about whether funding will be continued into the next fiscal year, which disrupts program continuity49. This colonial approach to community programming and government stipulating how programs operate has been shown to negatively affect Indigenous health and wellbeing54.

An effect of the First Nation band governments taking the lead on sports and recreation programs rather than these being grassroots initiatives is that community members become reliant on the First Nation band government and are less inclined to volunteer. Caregivers also discussed the expectation that the First Nation band government will finance, staff, equip and transport children to community sports and recreation programs. This expectation is similar to what Richmond and Ross55 have termed 'loss of life control' whereby community members have become less self-reliant and more dependent on the Canadian government and local band governments for health and social services. This feeling of disempowerment may be part of the cycle of 'welfare dependency' created by colonial policies56. Keeping children indoors and away from animals, drugs and alcohol, apprehensions, and assaults is a way to keep children safe and is a response by caregivers to counteract the 'loss of control' experienced in their lives as a result of colonial policies and legislation.

Implications for childhood physical activity programs

This study shows that simply advising parents to stop buying electronics for their children or to sign their children up for sports programs is unlikely to improve physical activity and the prevalence of obesity among children in Indigenous communities. This is because there are other factors that strongly influence physical activity among Indigenous children, and many are deeply rooted in colonial history. Foremost, community safety concerns need to be addressed in order to remove barriers to physical activity. Specifically, related to animals, dog management programs need to be established so that children can play outside without the risk of being bitten. Education on how not to attract bears into the community (ie taking proper care of household garbage) as well as traditional teachings about co-existing with bears should be done.

While the higher rates of addictions require long-term community approaches, in the short term the immediate risk for children who play outside should be reduced. For example, efforts to prevent risky behavior among children include the Drug Abuse Resistance Education program that has been delivered by the tribal police since 1997 and has reached 600 children in the Manitoulin First Nation communities (R. Nahwegahbow, personal communication, 2014). Public health campaigns about impaired driving should be developed with local statistics about its impacts. Increasing the police presence in communities through regular patrols and RIDE spot checks can reduce the number of impaired drivers.

Community sports and recreation programs need to be sustainable with flexible funding that allows for programs to be adapted to community aspirations and needs. Involving community members in the planning and implementation of community recreation programs can alleviate the feelings of disempowerment. Health messaging that is aimed at families being physically active together can address safety concerns. For example, walking children to school rather than riding the school bus or giving them a ride is an activity that many caregivers who live close to schools should be able to do. Family participation in traditional activities like hunting, fishing, gathering or making maple syrup are ways to be physically active and continue cultural activities. The practice of children helping their grandparents with chores should be encouraged as this can be a good form of physical activity and also supports the intergenerational transmission of knowledge, beliefs, and values. Further research examining the role of traditional cultural activities and children's wellness should be explored in these communities.

Conclusions

A socioecological approach has been used to identify the determinants of physical activity among Indigenous children in six rural First Nation communities. The findings show that there was a dynamic interrelationship among the proximal, intermediate, and distal determinants of physical activity in the participating communities. The levels of influence include caregivers, the community environment, broader society, and colonialism. These levels are illustrated in Figure 1, adapted from the socioecological model developed by Willows et al7.

Caregivers perceived dangers to children from animals, exposure to drugs and alcohol, the child welfare system, and assault, and sought to create safety by keeping children indoors, which is a significant change from previous generations. Caregivers also reported on the tendency to indulge children with electronic devices in response to material scarcity experienced in childhood. The proliferation of electronic devices combined with the desire to keep children safe has resulted in an increase in sedentary activity. Caregivers also reported on low volunteerism, declining parental commitment, and reliance on the local First Nation band government to fund, organize, and staff community sports and recreation programs. This disempowerment stems from the colonial legacy of government control over Indigenous peoples living on-reserve.

Technological improvements in community infrastructure have resulted in a better standard of living, with running water and sufficient electricity to run numerous appliances. This has resulted in a decrease in physical activity, with children no longer required to perform strenuous chores necessary for the functioning of a household. Although they continue to lag behind nearby municipalities, the socioeconomic conditions have improved in these communities, with some who are able to purchase recreational technology for their children.

Colonial policies and unstable funding for programs continue to impede progress towards solutions that address the pathologies created by colonial policies, namely substance abuse and sexual assault. Colonial policies continue to disempower Indigenous peoples and impact the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples living in these six First Nation communities. Community based research and strategies to address physical activity and safety are important ways to ameliorate physical inactivity and obesity in these First Nation communities.

Figure 1: Ecological model for understanding obesity in children.

Figure 1: Ecological model for understanding obesity in children.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the health staff and community members in the following communities for their contributions to this study: feck Omni Kaning First Nation, M'Chigeeng First Nation, Sagamok Anishnabek First Nation, Sheguiandah First Nation, Sheshegwaning First Nation, and Whitefish River First Nation.