Introduction

Stroke is Australia’s second single greatest killer after coronary heart disease and a leading cause of disability. Findings of the 2009 National Stroke Foundation Acute Stroke Audit provided clinical data that described a disparity in acute stroke care between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians1. The National Stroke Foundation has identified that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely to have a stroke at a younger age than the non-Indigenous population, and are twice as likely for stroke to result in death1,2. The most effective way of reducing death and disability following a stroke is through the integrated and coordinated care provided by a comprehensive stroke unit that combines acute care and rehabilitation1.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stroke survivors are less likely to have access to treatment and rehabilitation than non-Indigenous peoples1,3,4. Furthermore, those who were able to access acute stroke facilities received a reduced quality of stroke care in the same hospitals than non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stroke survivors; they were less likely to be assessed by allied health clinicians for rehabilitation, had a reduced rate of inpatient aspirin prescription or antithrombotic prescription on discharge when the patient had an ischaemic stroke and had limited if any access to community based rehabilitative care2,4.

In response to these statistics, the 2010 Far North Queensland Guidelines proposed that special attention and resources were required to develop an inclusive and responsive service model for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples5. While this acute clinical data existed, little investigation had been conducted at the time that explored the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stroke survivor experience or attempted to identify stroke care requirements specific to the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in rural and remote locations. The Aboriginal Stroke Project2, conducted in Western Australia in 2003, did explore the experiences of Aboriginal stroke survivors and health providers. While the findings had potential to inform the development of stroke services nationally the authors concluded that the results could not be extrapolated to other Aboriginal groups outside the pilot site. In recognition of the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations and the lack of evidence regarding the experience of Torres Strait Islander persons in particular further research was required to consider the experiences of these populations within Queensland.

Methods

Study site

In 2014 the general population of the Far North Queensland region was 275 216, of which 11.8% were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples6,7. Of the state’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, 25.6% live within Far North Queensland, and with 77 different Traditional Owners within the North Queensland catchment there is vast cultural diversity7,8. The Far North Queensland region is serviced by the Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service, and the Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service. A vast geographic area is covered by these two health services9.

Far North Queensland has only one hospital, located in Cairns, with an endorsed acute stroke unit and the capacity to provide specialist neurological rehabilitation. This unit treats six times more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients than the Queensland average10.

Study design

In response to the 2009 Far North Queensland Audit results, three hospital and health services within Queensland received Closing the Gap funding from the Council of Australian Governments Making Tracks program between 2011 and 2016 to address the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stroke survivors within their respective regions. The overall aim of this project was to establish a culturally appropriate model of service delivery that met the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stroke survivors. The project consisted of two phases within the Far North Queensland site. Phase 1 consisted of both a retrospective clinical audit and discussions regarding culturally appropriate pathways. Phase 2 used the information gathered in the initial phase to tailor the development of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stroke service in Far North Queensland. The qualitative study reported here was a component of phase 1. This article details the findings from structured interviews with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stroke survivors, their carers, family members and stakeholders.

Participants and recruitment

Participants from 18 diverse Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander communities agreed to take part. Study participants consisted of three groups: stroke survivors, their carers and stakeholders. Using a combination of convenience, opportunistic and purposive sampling a variant, information-rich sample of patients, carers and stakeholders were recruited.

Stroke survivors and their families and/or carers were identified through health centres and hospitals, and engagement was facilitated through Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers at the primary health care centres and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander liaison officers at the hospitals. These health workers and liaison officers contacted the stroke survivor or family member to obtain consent and arrange the interview. Stakeholders comprised clinicians involved in direct and indirect stroke care across acute, subacute and primary health, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, and representatives from non-government organisations and government organisations involved in clinical care or providers of support services for stroke survivors and community representatives.

Informed voluntary consent was obtained from interview participants prior to interview. Interview participants were offered interpretive assistance and cultural support from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers or liaison officers.

Data collection and analysis

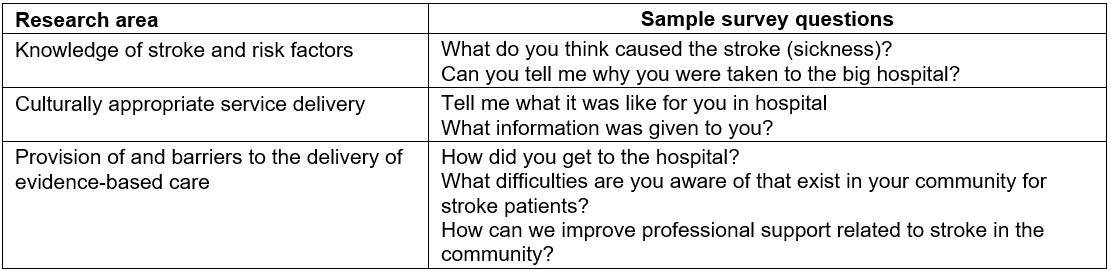

Surveys that included open-ended questions were administered through interviews with 104 participants (10 carers, 24 stroke survivors from 1 month to 5 years post-stroke, and 70 stakeholders). These interviews took place in 18 regional, rural and remote sites between June 2012 and November 2013. The interviews were conducted in stroke survivors’ homes, community facilities, hospitals and primary health care centres. The surveys were specific to each participant group and were designed to elicit illustrative comments around the research areas described in Table 1.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researcher (SB-E) conducted most interviews. The interviews were recorded and then transcribed. NVivo v9 (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/support-overview/downloads/nvivo-9) was used to manage and store the data.

Guided by the principles of thematic analysis11 the data were coded, categories created and themes and subthemes identified. One team member (RQ) coded a random sample of six transcripts (two each for consumer, carer and stakeholder) and developed an explanatory coding framework. The framework was reviewed and refined by two further team members (JM and ES). All the transcribed interviews were coded by one qualitative researcher (RQ), with a second qualitative researcher (JR) checking and advising on coding requiring clarification. RQ and JR worked inductively to generate themes and subthemes from the data. Representative extracts were coded to represent stroke survivor (SS), carers (CAR) and stakeholders (SH) and, in the numerical order recruited, were selected to illustrate the themes.

Table 1: Research areas and examples of survey questions

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC/11/QTDD/63).

Results

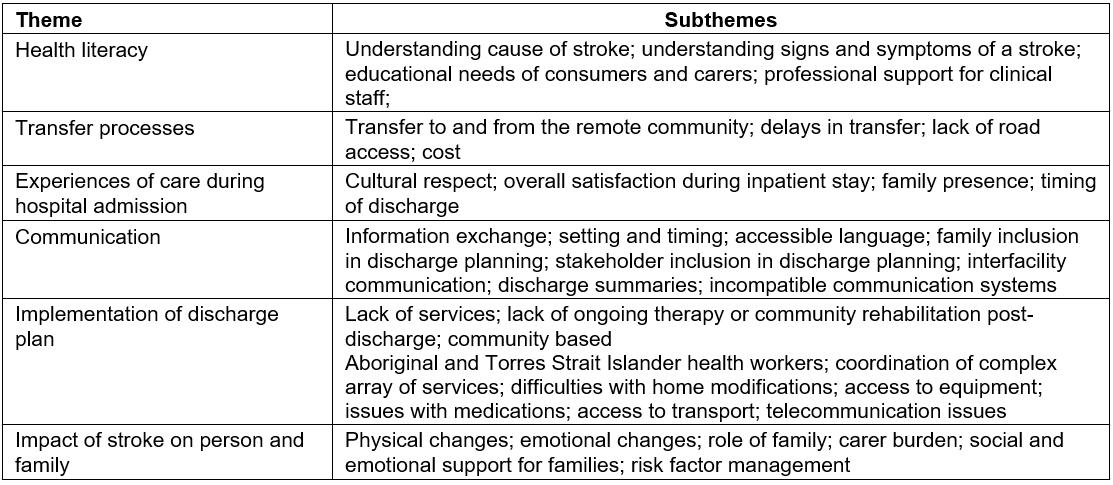

Data were grouped into six broad themes and related subthemes as shown in Table 2. The themes are presented as a representation of the patient journey from the perspectives of stroke survivors, carers and stakeholders.

Table 2: Factors impacting delivery of stroke care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Health literacy

There was little understanding from stroke survivors around the risk factors of stroke, and poor awareness that they had had a stroke post event, for example ‘I don’t know [what caused the stroke]. I didn’t know I had a stroke’ (SS 01). Most carers lacked confidence in their capacity to determine if their family member was having another stroke and how to respond appropriately. As CAR 04 stated, ‘I don’t even know what the signs are’.

While interviews strongly indicated clinical staff (nurses, doctors and allied health) felt confident in their stroke knowledge and understanding of stroke risk factors, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers indicated they lacked knowledge and the necessary skills to be able to talk to their community about stroke. The need for learning opportunities for these health workers was described by one stakeholder.

It would require a total training package to talk about different strokes in different parts of the brain, what gets affected, what we should be looking for what we should be educating in and teaching families. I have no idea, just the basics of stroke is all I know. (SH 21)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers indicated that having improved knowledge would allow them to be more proactive in raising community awareness and have a greater influence in primary prevention.

Transfer processes

With a catchment area of more than 300 000 km2, transfer to the acute stroke unit by road, air and sea is dependent on availability and access. Many Cape York Peninsula and Torres Strait Islander communities are isolated during the wet season.

She managed to get to the phone to ring the clinic .. .the clinic went over and picked her up. They had to assess her and get her ready and then of course you’ve gotta wait and see if there’s an available plane to come up. (CAR 04)

Public and charter transport options were deemed by participants to be costly and created challenges for family members to accompanying stroke survivors to regional hospitals.

Transport to the nearest health service immediately following a stroke was also discussed as problematic due to geographic isolation and lack of transport options. Transfers that involve multiple transition points were reported as taking several days of travel, with significant impact on rapid treatment provision.

Experiences of care during hospital admission

Stroke survivors emphasised that access to family members during the hospital stay was important.

I would rather stay close by with the family member you know close by, even in the hospital the family member needs to be there because when we are stuck by ourselves we get more sick. We worry too much. (SS 02)

However, having an escort present was often unachievable due to logistics of the escort being away from Country and the costs involved: ‘I don’t think a lot of family come to visit him because of the cost’ (SH57).

For many stakeholders there was a lack of cultural respect. Identified issues included a lack of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander liaison officers, shared mixed gender hospital rooms, poor cultural training for staff across the facility, poor valuing and understanding of cultural diversity, poor communication and deficits in organisational strategic directions.

Things like putting [people in] shared [mixed gender] wards shouldn’t happen in a facility in a regional place like this ... It does happen and it impacts on their [patient] well-being. We don’t sleep in a room with their brothers or our male family members. It just doesn’t happen when you are adults … (SH 48)

Timing of the discharge from the major hospital was frequently discussed by participants. Stroke survivors generally indicated that they were keen to return home to their community as soon as possible. Reasons given were overwhelmingly linked to missing family, especially for those who had had a caring role themselves for children, spouses or parents: ‘I had to come back – that was in the back of my mind, the children’ (SS 07). Others identified guilt of having escorts also away from home and the associated costs of them for both being away from work and having to pay for temporary accommodation in the regional centre.

Generally, stroke survivors were willing to sacrifice access to further therapy to return more quickly to their community: ‘They wanted to keep me in there [major hospital] for all that exercise but I said no I will do it in my home every day in [community name]’ (SS 06). However, carers and stakeholders felt it was important that the patient accessed as much therapy as possible in the regional centre before returning home and indicated that often the patient was discharged too soon. As one remote stakeholder described, ‘most of them would return [to community] and go without the facilities [rehabilitation] so they can be home, they would rather be home without, than get themselves better staying away’ (SH 08).

Communication

Timeliness of information and use of accessible language and translators were considered paramount for effective communication and education: ‘I think they don’t understand – English is our third language they just say yes yes yes but I think they don’t know. They don’t understand’ (SH 38). Evidence of poorer health outcomes because of poor health literacy was also referred to: ‘They failed to send an escort with him and when he woke at [hospital] because he couldn’t understand what they were talking about he refused medical help’ (SH 62). Furthermore, there was consensus that the communication between providers and patient and family was inadequate. A priority need was the identification of an appropriate family member to ensure the correct information is received, understood and shared with the relevant family members: ‘I don’t know if they involved the daughter in a lot of those discussions it certainly didn’t get back to the rest of the family’ (CAR 04).

Many participants felt that family inclusion and effective communication were absent during discharge planning from hospital. Specifically, poor engagement of communities and family within the discharge planning process was deemed detrimental to the patient’s care.

It’s a bit silly to give the patient the information … rather than have just a little family conference to say this is what’s happened, this is going to happen and what to expect, what role the family could play in helping her? There could have been something that we could have been doing as well to help her. (CAR 04)

Stakeholders from remote areas found the communication between facilities to be poor especially around communication of the discharge date and discharge plan: ‘Their discharge summaries are a summary of what’s been done in the hospital but not an ongoing care plan’ (SH 29). The plan for follow-up therapy back in the community was often left to chance.

I think more information could be given out. I don’t think there’s enough importance put on seeing the physio, the OT [occupational therapist], the speech therapist. I think a lot of people are just sent home and told to go to one if one happens to come through rather than this is part of your recovery plan. In order to get back to where you possibly were before you had the stroke, it’s important that you attend these things. (CAR 04)

Delays in receiving discharge summaries meant that patients weren’t always receiving the most appropriate care from either the health centre or families.

We have problems getting discharge summaries. They arrive 3–4 weeks after the patient is back in the community. It’s a huge problem because we have to follow them up when they come back to the community – it’s hard when we don’t know what we’re supposed to do with them. (SH 07)

Implementation of the discharge plan

Identified challenges to effective implementation of discharge plans included difficulties in access to provision of home modifications, equipment, medications and transport. Some areas reported a lack of transport, day or home respite or domestic assistance services with the burden of care falling onto family members: ‘There’s no HACC [home and community care] services, there’s no home care services no aged care services’ (SH 57).

Participants discussed further challenges posed by poor telecommunications, the wide range of siloed government and non-government agencies involved in implementation of the discharge plans, infrequent site visits by allied health staff such as physiotherapists and lack of locally based community outreach staff. Lack of provision of ongoing therapy had in some cases resulted in the consumers not fulfilling their rehabilitation potential and having to enter residential care: ‘There was one fella from [community name] – we ended up putting him into a home as the follow-up was not fantastic and that’s why he had to go up there’ (SH 01).

Impact of stroke on person and family

Whilst stroke survivors tended to focus on the physical aspects and deficits around function, carers and stakeholders reflected more on the emotional and psychosocial aspects of stroke and identified the increased risk of depression amongst stroke patients: ‘We got all the physical things to look out for but some of the mental health thing we don’t know what effect it’s had on their minds as well’ (CAR 04).

Carer burden was recognised by participants as a concern: ‘It often falls to one person to look after that person who has had a stroke. So there is a huge carer burden’ (SH 39). Family were ill-prepared for the caring role, which included providing ongoing therapy and personal care. Lack of support services, emotional support, financial support, carer education and training and respite options for family were identified as issues.

Discussion

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from rural and remote communities in Far North Queensland face barriers to accessing quality stroke care that span the care continuum. Many study participants not only had difficulty recognising that they or their loved one was having a stroke but had to overcome often significant geographic and environmental barriers to access the right care. Furthermore, it is clear from these results that active patient engagement in acute and rehabilitative processes provided at the main hospital is dependent on a culturally safe therapeutic environment. While the findings are consistent with those from Western Australia, a deep understanding of additional issues important to Far North Queensland stroke survivors has been achieved, identifying the importance of involving family in all stages of stroke recovery and the need for comprehensive and collaborative discharge planning.

Opportunities for primary prevention, early intervention and education

Awareness, knowledge and experience of stroke were largely absent from participants’ experiences illustrating the need for raising stroke awareness among Indigenous people. Recent Australian Government policy development has addressed stroke prevention through lifestyle change and stroke-specific health education campaigns, such as Know Your Numbers and Strokesafe facilitated by the National Stroke Foundation11. Despite these national programs, the need exists for improved implementation in remote settings of these programs and better utilisation of specifically designed Indigenous resources such as Journey after stroke12, produced by Queensland Health and the National Stroke Foundation. Promotion of stroke health literacy requires culturally appropriate health literacy initiatives and ongoing capacity building opportunities for health staff, particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers13-15.

Culturally appropriate care

Cultural perspectives and needs can influence decisions about help seeking behaviours, adherence to health enhancing strategies, the success of prevention and health promotion activities, and views about a facility and its staff. By developing a culturally safe environment patients feel safe and respected13. Artuso et al report that Aboriginal people utilising health services experience a wide range of barriers including communication problems, institutional racism, lack of cultural awareness and loneliness13. Patients often rely on family members for support, and during a hospital admission these people can be called upon to act as interpreters, assist in navigating the complex health system and provide social and emotional support.

While stroke survivors and carers expressed the desire for family members to travel with them, eligibility criteria, cost and practicalities made this difficult. Yet, their presence often improves patients’ agreement to being transferred to tertiary hospitals and is essential for self-management and improved health outcomes13. This study identified gaps where family were unable to act as escorts but were wishing to be involved in care planning. Families within this study felt specifically excluded from involvement in discharge planning, yet numerous studies have reported the value of involving the patient and carers in effective care transition processes, specifically discharge planning16,17. The family or carer is often the only consistent person involved with the patient across the care continuum, and pre-discharge family meetings can reduce psychological distress of family carers and assist in meeting their information and support needs17,18. Artuso et al found that family involvement has benefits for consumers around their utilisation of health services including follow-up care and that early discharge from hospital combined with lack of appropriate planning can contribute to carer burden13,16.

Further efforts to develop a culturally appropriate inpatient environment would allow patients to feel safe and respected. Cultural safety is achieved when the recipients of care deem the care to be meeting their cultural needs19,20. This may include gender appropriate care, which is highly regarded amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people13. Increased use of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander liaison officers within the inpatient setting can also reduce barriers associated with communication difficulties, fear and mistrust of a western model of care.

Community-based care

The importance of staying on Country, of Law and language for the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members and the provision of community based culturally safe services to facilitate access to care has been thoroughly documented19,21. For the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to improve, they must have access to appropriate, affordable, acceptable and comprehensive primary health care22. Stroke survivors within this study were required to leave community to access stroke care and forego ongoing rehabilitation to return to country. Yet it has been well documented that organised multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs in post-acute settings result in reduced dependency after stroke5,23. For many stroke survivors the transition into residential care may be averted by further community based rehabilitation and provision of support services16,17.

The primary responsibility of providing care to a person after stroke often falls to family17. Support for carers of patients with stroke across the trajectory is crucial as stroke can have significant psychological impact on carers, who often feel unprepared to deal with the physical, cognitive and emotional demands placed on them17,18. Ongoing support for family is crucial and may include emotional and financial support as well as practical assistance such as appropriate training and access to necessary equipment, modifications, appropriate information and various respite options.

Communication between service providers

Effective communication between service providers can be impacted by the number of transitions the patient experiences, incompatible information systems, inadequate transfer of written discharge summaries and the disjunct between providers. Some of the patients involved in the study had up to 10 care transitions between differing locations within their stroke journey.

Poor communication and handover at each point of transition can compromise patient safety and the quality of care16. At each point there is a risk that care plans are not handed over, which could undermine any gains made in the preceding setting16 and increase the chances of medication errors, poor case management and inadequate continuation of care. Improved liaison, cooperation and coordination of services between providers could facilitate return to Country and improve timely implementation of equipment, modifications, medications and support services.

A strong theme discussed by stakeholders was the inadequate written communication between facilities, specifically discharge summaries. Many stakeholders felt there were inexcusable delays of up to several weeks before discharge paperwork arrived in the community. A discharge summary is an important document that is both a permanent record of a patient’s visit to hospital and the primary means of communication between hospital services and primary care providers24. Ensuring adequate details of follow-up, management plans and referral information is crucial to optimal continuity of care24.

Cross-organisational communication strategies and systems of information exchange are essential to optimise integration between services and improve care coordination across the continuum of care25. Patient-held information systems that can be shared between providers within organisations, such as ieMR in Queensland Health, and across organisational boundaries, such as My Health Record nationally, may go some way to facilitating improved information exchange.

Workforce development

A shortage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers in the primary health care workforce was identified, reflecting findings from Gibson et al22. Identified benefits of these health workers in the workforce are improved engagement of patients, a friendly and relaxed patient environment, provision of cultural safety, integration of cultural protocols26 and, when trained, an improved ability to provide regular health checks and education about health risks and self-management27. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers can create safe space for inquiry and conversation rather than a didactic approach often experienced by consumers. However, to be effective they require role clarification with the PHC team, appropriate training, and local supervision and support27.

Given the need for assistance with home-based rehabilitation in the remote community setting, the health workforce could be enhanced by community based allied health assistant positions, providing opportunity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers to extend their scope of practice. Further, mentoring relationships between nurses and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers should be an integral part of practice. These professional relationships may result in reciprocal learning28, contributing not only to improved provision of culturally safe services but also to building a whole-of-team approach to evidence-based practice.

Stroke specialist services

Participants highlighted the lack of access to a stroke unit. There is overwhelming evidence that stroke unit care significantly reduces death and disability after stroke compared with conventional care in general wards for all people with stroke5,29. Compared to a general medical ward, treating patients in an acute stroke unit will prevent 56 patients from dying or becoming disabled per 1000 patients treated, and prevent one death or disablement per 18 patients treated5. Furthermore, a randomised controlled trial comparing an extended stroke unit service characterised by early supported discharge has been shown to improve outcomes, such that the number needed to treat to achieve one independent patient compared to conventional stroke unit care was nine30.

Evidenced based acute stroke care demands patients be transferred immediately to the acute stroke unit from the emergency department, ideally within 3 hours of presentation. However, many participants who could access stroke unit care were not admitted until several days after onset.

Study limitations

This study has some limitations. The interviews were conducted during an 18-month period; however, at the close of this period the new multidisciplinary stroke team focused on the care of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had already been established within the regional hospital. Some comments from stakeholders reflected the change of practice. Some stroke survivors and their carers were interviewed several years after the stroke so may have had difficulty recalling their experience of the acute stroke phase of their journey. The interviews, while sampling stroke survivors at varying times post-stroke, were conducted cross-sectionally rather than longitudinally and do not capture the participants’ changes over time. Stroke survivors in nursing homes were not interviewed so the experiences from this population are not included. This is of significance as it is often these survivors that have had to leave communities and families. The strength of the study was the inclusion of participants from across 18 different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rural and remote communities within Far North Queensland.

Conclusion

The National Stroke Foundation recognises that the stroke care needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people requires attention. This study emphasises the need for an integrated approach to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander model of stroke care that crosses healthcare boundaries and links primary and secondary health services. A coordinated and culturally responsive model of care is required. Effective stroke care values the role of the client, their family and community in enabling optimal therapeutic engagement and facilitating a timely and well-planned discharge. This includes consultation with the primary health clinic from the moment of hospital admission through to discharge, meaningful engagement of family in therapy interventions and discharge planning, and timely dissemination of discharge paperwork.

While culturally appropriate practice is the responsibility of all, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander liaison officers have a pivotal role within the multidisciplinary inpatient team for the leadership of culturally safe work practices and promotion of patient and family support for the duration of their hospital stay, as do Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers for the achievement of health service engagement and optimal community based rehabilitation.

Acknowledgements

We thank all stroke survivors, their carers and stakeholders who took time to participate in the study.

We respectfully acknowledge the health workers and staff from the following Aboriginal and Torres Strait Health Services that assisted in this study: Badu Primary Health Care Centre (PHCC), Bamaga PHCC, Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service, Coen PHCC, Cooktown Multipurpose Health Service, Darnley (Erub) PHCC, Hopevale PHCC, Kowanyama PHCC, Laura PHCC, Lockhart River PHCC, Mapoon PHCC, Mossman Health Service, Murray Island (Mer Island) PHCC, Napranum (Malakoola) PHCC, Pormpuraaw PHCC, Thursday Island PHCC and Hospital, Weipa Integrated Health Service, Wujal Wujal PHCC, Iama (Yam Island) PHCC and Gurriny Yealamucka Primary Health Care Centre (Yarrabah).

We acknowledge contributions by Annabell Hartnell, Margaret Grasso and Cherelle Stager in the data collection phase.

The following organisations were critical in the establishment and support for this project: Rural Stroke Outreach Service, Apunipima Cape York Health Council, National Stroke Foundation, Queensland Health Stroke Clinical Network and Queensland Health Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Branch.

The contributions made by Cindy Dilworth, Alena Scurrah, Damianne Clifford, Dr Martin Dunlop, Dr Edward Strivens, Mary Streatfield, Linda Baily, Dr Donna Goodman, Amanda Wilson, Emma Burchill, Layla Schrieber and Dr David Williams in the establishment of this project are acknowledged.

References

You might also be interested in:

2006 - SEAM - improving the quality of palliative care in regional Toowoomba, Australia: lessons learned