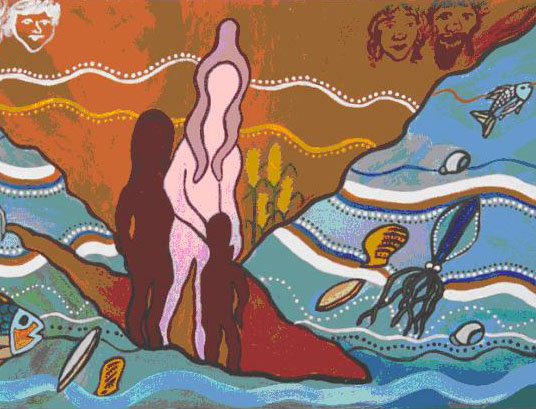

A painting by a local South Australian artist expresses the feelings of many Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the Gallinyalla community, South Australia (Fig 1). It captures the uniqueness and richness of both the human and natural environment, reflecting the quality of life, and the diversity of the environment and the people within it.

Figure 1: 'This painting is about how everyone can join in, help and look after each other and live in harmony'. Joylene Johncock © 2002, reproduced with permission.

Acknowledgement

Acknowledgements are usually placed at the end of an article. To break with this tradition, and as an acknowledgement and tribute of respect for the first people of Australia, the author thanks the custodians and Aboriginal people of Gallinyalla. This article could not have been written without working in collaboration with every person involved in the project, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal. Therefore, the second acknowledgement is to the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people of the Gallinyalla community, South Australia, who worked together in equivalent intercultural working partnership to make this study happen. The artist Joylene Johncock created the Gallinyalla painting. The Kuju artists Jackie Nannup, Minnie Miller, Leah Laughton, Sharon Liddell, and Marcus Liddell produced the visual representation from their focus group. The Substance Use Advisory Group offered advice and continued commitment to the process of the study. Jackie Ah Kit gave organisational and personal support; Neil Sercombe lent invaluable support during the study and expertise in editing the final report; Michael Wallis had involvement in the study design; Sharon Potts, Jenny Barker, Bronwyn Hollands, Charlotte de Crepigny, Sue Mills and Helen Murray gave good counsel and support during the study. Angela Francisco was outstanding in her role as an administrator and confidante. Vicky Gould helped with contacts and in many other ways.

Introduction

The Land and the People

Gallinyalla is the local name for a beautiful and picturesque town at the edge of the Spencer Gulf, South Australia. It is a place where the land meets the sea. It is home to diverse communities and cultures, which include many ethnic groups from around the world. It includes areas of national parks, and also rich agricultural and marine environments, which have led to the establishment of prosperous farming, fishing and tourist industries.

The two Aboriginal claimants for the Gallinyalla area are Nauo Barngarla/Barngarla Nauo peoples who have accessed the resources of the land and sea in this area for thousands of years, caring for the Dreaming, Kinship, and Land in keeping with the structure of their Aboriginal culture and as part of their custodianship. Since European settlement of the area in 1839, Aboriginal people have continued to maintain their traditional historical, spiritual, physical and emotional ties with the land in spite of displacement and accompanying changes to their ways of life (B Richards, oral presentation, 2005).

In 2001 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) figures1 stated that the Aboriginal population of Gallinyalla was 622, 4.7% of the total population of 13 199. The Aboriginal population is likely to be under-represented by the ABS as a result of inaccurate enumeration during census collection. A local database maintained by the community-controlled Aboriginal Health Service demonstrates significantly higher population figures (J Ah Kit, pers. comm., 2002).

In contemporary life, Aboriginal people are proud of their still-strong family ties. The Aboriginal community members in Gallinyalla have established many Aboriginal community-controlled services2. There is a strong commitment in Aboriginal organisations to work with mainstream institutions, always mindful of not relinquishing their autonomy, while working together towards reconciliation3.

The need for this research was identified through individual and community sources. Aboriginal substance use has a high profile in the region and dealing with this is a major priority for the Aboriginal Health Advisory Committee (AHAC). The community-controlled Aboriginal health service also highlighted the need for, and had obtained funding to, develop local strategies to address substance use in the Aboriginal community (J Ah Kit, pers. comm. 2002). Because substance use involves the whole community, a multi-agency approach was established. The view that many of the substance use issues faced by Aboriginal people today are outcomes of past injustices has also been reflected in the findings of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody4 and other reports and studies5.

Previous studies in other Australian communities had demonstrated that alcohol, tobacco, medicines and/or drug use were issues of concern6-8. More recent studies have confirmed that these challenges remain9-11 and that effective substance use strategies are needed. These are best developed and sustained in cooperation with Aboriginal community organisations.

This study, which is part of a larger project12, had the following objective: to identify the scope of substance use and its impact on the Gallinyalla community, and to provide data that will enable policy makers and service providers to develop and evaluate interventions.

This study represents the collective views of both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and government and non-government agencies and their efforts to research and develop an understanding of substance use in the Gallinyalla area.

Methods

This study used a mix of qualitative methods (focus groups and semi-structured interviews) and quantitative methods. A 22 person substance use advisory group were representatives from 18 agencies (Aboriginal n = 7; non-Aboriginal n = 11) at the beginning of the research project. This group developed and approved the four major themes into broad questions for use in the focus group process. The questions sought views on: (i) the drugs of concern; (ii) the perceived understanding of the substance use issues in the community; (iii) solutions to address substance use; and (iv) exploration of what adequate services would look like.

A number of individual free-flowing interviews were then carried out utilising the researcher's community contacts and kinship links. A form of snowball sampling technique was used13. This relies on initial participants generating additional participants. Therefore, only those who had been suggested and approached by word of mouth, and who had been willing to take part, became the final sample. The interviews offered the researcher and community members the opportunity to discuss substance use issues and, from there, it was possible to develop prominent themes and set the scene for the focus groups.

As part of the interview and focus group process, each participant was invited to complete a questionnaire that included their ethnicity, age and gender. Focus groups then went on to discuss their views of the local situation using the four broad questions above. Potential members of the focus groups drawn from all the Aboriginal community controlled organisations were initially contacted by telephone, letter, or face to face. If necessary, a telephone call reiterated the written invitation.

The final questionnaire and focus group questions were piloted using a representative group of five Aboriginal and two non-Aboriginal community members. The instrument demonstrated good face validity, requiring only minor modification prior to use within the project.

Traditionally, mainstream ethics approval is sought through a hospital or university research and ethics committee. In this study, ethics approval was sought through community consultation and negotiation. This led to a plan and approval of what Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Gallinyalla defined as the issues of substance use, drawing on interviews and focus groups to address the study objectives.

Quantitative data was collated using Microsoft Excel. For the qualitative data, analysis was undertaken through reading the transcripts of the groups and interviews and drawing out the common themes. Analysis of these themes was also discussed with the substance use advisory group. Where views differed among advisory group members, key transcriptions were reviewed and discussed until consensus was reached. All material from focus groups and interviews was treated as confidential.

Results

In total, 285 individual interviews (Aboriginal n = 160, non-Aboriginal n = 125) and 24 focus groups (Aboriginal n = 58, non-Aboriginal n = 153) were conducted (Table 1). The focus groups were held from August to December 2002. Group size ranged from two to twelve. Each group had a facilitator and scribe to take notes. It was noted among the Aboriginal cohort that individual participants preferred to be interviewed rather than take part in a broader focus group setting.

A total of 218 out of 622 (35%) of the Aboriginal population of Gallinyalla participated in this study. In regard to the non-Aboriginal population, 278 out of 12 577 (2.2%) participated13.

A broad section of the community was represented in the focus groups ranging from five Aboriginal community organisations, and also Country Women's Association, Rotary, police, prison, TAFE, the high school, health services (including community, hospital and mental health staff), church groups, women's shelter, city council, ambulance services, a local pharmacy and the Eyre Regional Development Board (Tables 1,2).

Table 1: Summary of focus group and interview participants by gender and ethnicity

Table 2: Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal focus groups by age group and gender

The interaction between the participants and the facilitator within the sessions became pivotal to gaining an understanding of how the community perceived the impact of substance use on their daily lives. Participants responded in a variety of ways to the questions in each focus group.

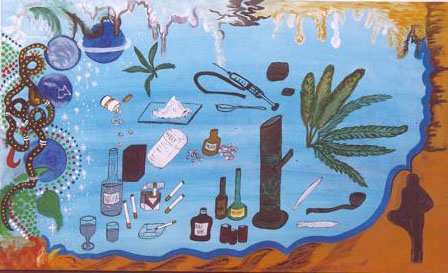

One group created a powerful visual image of the complexities of substance use for the individual, for their family members, friends and for their community (Fig 2). A painting provided a mechanism for participants to discuss the issues through commentary about the images they had produced rather than directly responding in a linear form to the set questions.

Figure 2: Painting from one focus group. Artists: Jackie Nannup, Minnie Miller, Leah Laughton, Sharon Liddell and Marcus Liddell © 2002, reproduced with permission.

Members of the focus group described the painting in their own words as follows:

Nunga: The word Nunga refers to an Aboriginal person from South Australia. He is standing there and can see how drugs are affecting our community and our culture.

Dots: Represent dreaming, but not Nunga way, spinning out or hallucinating, that is why the dots are not in Nunga colours.

Meltdown: Represents the meltdown of our community and the tear in the meltdown represents how it is ripping our world apart. The meltdown of our community and breakdown in communication as people don't want to associate with those who use needles.

Snake pattern: Which is not a snake, but represents confusion in Aboriginal people and their culture dealing with drugs and alcohol.

The blue: The blue background represents feeling blue when you're confused with drugs and culture.

What is the first thing that you notice in this painting? The drugs! It shouldn't be like this, they should be in the background. See how drugs are destroying our culture and our world! We need to turn this picture around.

Summary of key findings

What are the drugs of concern? In response to this question a number of common themes emerged in which there was a great deal of agreement (Fig 3).

Figure 3: Drugs identified by focus groups in order of significance.

All members of the focus groups, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, reported a high level of alcohol consumption across all age groups and employment statuses. Women reported using drugs at an earlier age than males, and males who were unemployed were more likely to use drugs.

In the interviews conducted with both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal community members the greatest concerns were the widespread and excessive consumption of alcohol by young people. This resulted in anxiety and fears about alcohol use at a younger age. Reports included young people up to the age of 20 years consuming up to 30 alcoholic drinks in one night, young children walking the streets at night without adult supervision and concerns about the marketing of 'trendy' high sugar content alcoholic drinks. Concern was raised in relation to the practice of identifying a nominated driver, which seemed only to encourage others in the group to use drink and drugs even more excessively.

Marijuana was the next most identified drug of concern, especially when used with alcohol. Another widely-held concern related to amphetamine use. Tobacco was also identified and there was a high level of awareness of the ill effects of tobacco on physical health. Females reported higher tobacco consumption than males.

Excessive use of medications, both prescribed and non-prescribed (especially Panadol® and Panadeine Forte®) was also identified. Some members of the community were perceived to be 'doctor-shopping' to increase their personal supplies of medicines, leading to problems associated with over self-medicating or enabling people to sell or trade their prescribed drugs for other substances.

Heroin and methadone were also mentioned, as was a need for better access to a registered methadone program and needle disposal. Other concerns were the use of ecstasy and other designer drugs, high caffeine soft drinks, glue, petrol, aerosol and paint cans.

What are the substance use issues? The most commonly identified issues arising from excessive alcohol and drug use were loss of control and the associated behavioural changes and abusive behaviour ranging from physical to emotional violence. Further issues highlighted by the groups are presented (Fig 4).

Figure 4: Substance use issues and their impact on the community highlighted by the focus groups.

Polarised positions were revealed in a small proportion of groups. One perception was of substance use as a problem belonging to others, and another minimised the problem.

What are the suggested solutions? Participants suggested the adoption of broad community strategies to link and strengthen agencies that deal with substance use issues in Gallinyalla, and to promote the reconciliation process.

The most common strategy discussed was education programs, including prevention and drug awareness programs in both schools and in the broader community. Since the commencement of this project, on-going educational programs have been set up by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal counsellors from their respective health services working in partnership with school children and teachers at primary and secondary level. Mental health support services and Aboriginal organisations in partnership have developed prevention programs that have resulted in enhanced working relationships between agencies. In addition, calls for more extensive services for those living with substance use have resulted in the creation of an extra counselling position.

In 2005 a methadone program was set up following the work of the Gallinyalla Community Alcohol and Other Drug Committee. Two GPs are now registered to prescribe methadone. A detoxification and rehabilitation centre is high on the 'wish list' for Gallinyalla.

Discussion

In this study the host community - the first peoples of Gallinyalla - endorsed and led the research, established the need for a whole-population approach to the issue, and built the intercultural and intellectual partnerships necessary to conduct the research. This was the key that enabled access to a wide cross-section of the people and led to a high rate of participation in all aspects of the research. This took time, because the relationships, responsibilities and obligations of the people in Gallinyalla were involved. Coming from this position of strength, the findings are likely to accurately reflect the views of the overall community on substance use.

While the Aboriginal people in Gallinyala acknowledged there are substance use issues within their own community, and that Aboriginal people have the poorest health status in Australia, what was noteworthy about this project was an acknowledgement by the non-Aboriginal participants that although their own health status may be better, substance use was also tearing their families and relationships apart.

Working in intercultural and intellectual partnership has led to individual and organisational participation in the reconciliation process between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the Gallinyalla area. When a community can work together in this way, it will promote and enhance the health of not only Aboriginal people, but all people.

Conclusion

This study identified alcohol, marijuana and amphetamines as the major drugs of concern in Gallinyalla. It highlighted the social consequences, especially loss of control leading to physical and emotional violence. The implications for policy and practice from this research support the original contention of AHAC and others of the need for appropriate local substance use strategies. Building on the relationships developed during this research process, the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal community together are developing these strategies. In doing so, the community as a whole continues significant progress towards embracing the reconciliation process.

References

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Indigenous profiles, 2001. (Online) 2002. Available: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@cpp.nsf/cdbygeogtype!OpenView&Start=1&Count=1000&Expand=1.4&RestrictToCategory=Main%20Areas#1.4 (Accessed 24 April 2006).

2. Port Lincoln Aboriginal Health Service. Annual Report 2003. Port Lincoln, SA: Port Lincoln Aboriginal Health Service, 2004.

3. Aboriginal Council for Reconciliation. Roadmap for reconciliation. (Online) 2000. Available: www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/car/2000/10/pg2.htm (Accessed 17 April 2006).

4. Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. National Report by Commissioner Elliot Johnson. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1991.

5. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Bringing them home - National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Canberra, ACT: Sterling Press, 1977.

6. Hall W, Hunter E, Spargo R. Alcohol-related problems among Aboriginal drinkers in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Addiction 1993; 88: 1091-1100.

7. Perkins JJ, Sanson-Fisher RW, Blunden S, Lunnay D, Redman S, Hensley MJ. The prevalence of drug use in urban Aboriginal communities. Addiction 1994; 89: 1319-1331.

8. Hunter E. Is there a role for prevention in Aboriginal mental health? Australian Journal of Public Health 1995; 19: 573-579.

9. Ivers RG. A review of tobacco interventions for Indigenous Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2003; 27: 294-299.

10. Mark A, McLeod I, Booker J, Ardler C. The Koori Tobacco Cessation Project. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 2004; 15: 200-204.

11. Brady M. Historical and cultural roots of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Addiction 2000; 95: 11-22.

12. Franks C. Gallinyalla: a Town of Substance? Alcohol, Tobacco, Medicines and Other Drug Use in the Port Lincoln Community. Port Lincoln, SA: Port Lincoln Aboriginal Health Service, 2004.

13. StatPac. Snowball sampling. (Online) 2000. Available: http://www.statpac.com/surveys/sampling.htm (Accessed 7 December 2005).