Dear Editor

Tooth loss is associated with poorer oral health, compromised diet, nutritional deficiencies and reduced oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL)1. Aboriginal Australians have consistently poorer dental outcomes, and loss of teeth is overrepresented in Aboriginal Australians2. The Poche Centre for Indigenous Health is an organisation that forms partnerships with Aboriginal communities to co-design health services. Recently, a novel mobile denture service that fabricates dentures in a short time-frame of 4 days was designed and implemented by the Poche Centre at the request of the local Aboriginal community in northern New South Wales. The denture service is operated from a mobile clinic by an Aboriginal dental technician, pro bono prosthetists and the dental team hosting the visiting service. The hosting team includes dentists, dental assistants and oral health therapists. The service attends each host site for up to 5 days and operates approximately 12 weeks each year. The service is coordinated and primarily funded by the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health.

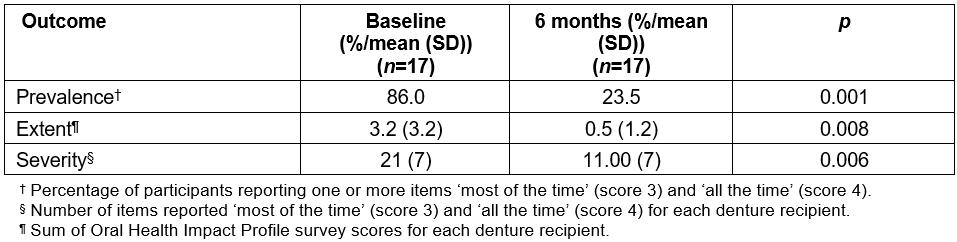

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of the service on OHRQoL of the patients who received the dentures. OHRQoL was assessed using the shortened version of the Oral Health Impact Profile survey (OHIP-14)3. Denture recipients between July and December 2016 were invited to participate in the evaluation, completing an OHIP-14 survey at baseline and 6-month follow-up (January–June 2017), in a culturally safe manner, as an interviewer-assisted survey with an Aboriginal dental assistant. Twenty-eight recipients (82%) participated in the survey at baseline, 17 (61%) were able to be followed up. The effect of oral health on quality of life was improved in all measurement scores. At baseline, 86% of the participants had at least one item scored as ‘most/all of the time’ for oral health problems; at follow up this dropped to 23% (p=0.001). The ‘extent’ of the effect of oral health on quality of life, the mean number of times a participant ranks one of the 14 items as ‘most or all of the time’, was also significantly reduced at follow-up (3.2 v 0.5, p=0.008). The ‘severity’ of the effect of oral on quality of life, the mean overall sum of all OHIP items, was 21 out of a possible 56 at baseline; this was significantly (p=0.006) reduced at follow-up to a mean of 11 for all participants (Table 1).

Whilst all dimensions of the OHIP-14 improved over time, changes in psychological dimensions were the most significant. These dimensions included being self-conscious (p=0.003), feeling ‘shame’ (p=0.006), being worried, anxious, embarrassed (p=0.008) or being less happy with life (p=0.01) because of poor oral health. The least amount of change was seen in the questions relating to eating and day-to-day living, which may be due to the short follow-up timeframe, not allowing for time to adjust to wearing the dentures. A longer follow-up time may have seen a further increase in improvements in these areas as participants adjusted to their dentures. Continued follow-up of these denture patients is paramount, in order to continue to see continual improvement in OHRQoL.

These results suggest that the denture program is improving the OHRQoL of the denture recipients, but most importantly the psychological impact of poor oral health on quality of life for Aboriginal people. Further research, including costs analysis, with a larger number of participants to confirm these results, could be conducted, including studies on how the provision of dentures may also improve overall mental health for the community.

Table 1: Summary scores for oral health related quality of life outcomes

Michelle Irving, Neelam Kumar, Anthony Blinkhorn, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sydney

Folau Talbot, Kylie Gwynne, Poche Centre for Indigenous Health

References

You might also be interested in:

2006 - SEAM - improving the quality of palliative care in regional Toowoomba, Australia: lessons learned