Introduction

Identifying factors associated with access to medical care for particularly at-risk individuals is necessary to inform action by health policy makers and community stakeholders1. This is increasingly critical as the number of middle-aged and older adults with chronic conditions is rising, due in part to the aging of the baby boomers2 and advances in medical care3. In addition to the high prevalence of those with one chronic condition, multiple chronic conditions are becoming more common with nearly three-quarters of older adults having two or more chronic conditions4. Thereby self-management of these conditions, with a goal of avoiding preventable complications, is more challenging. Older adults may be a particularly at-risk group in clear need of access to medical care in order to successfully age in their homes in a community setting, also referred to as successfully aging in place5, as opposed to residing in institutionalized settings like nursing homes.

With comorbid or concurrent chronic conditions comes increasing complexity (eg medication, potential for complications)6. This typically means that those with chronic conditions may need to visit healthcare providers to receive medical care more frequently, yet these same individuals may face barriers accessing care7. While this raises a set of issues related to keeping appointments and adhering to medical recommendations8, an initial barrier may be the amount of travel associated with getting adequate medical care. Transportation difficulties or long travel distance for medical care are associated with delayed care, poorer medication adherence, and foregone care9,10. This is especially true in rural areas, where resources are scarcer and additional travel distances are required to reach healthcare providers10. Rural health disparities have persisted over time and more work is necessary to continue to monitor gaps and advise on possible solutions in the realm of both policy and practice11.

Although it has been documented that individuals in rural areas travel further distances to receive medical care, these studies often examine one-way or round-trip distance9,12 and do not consider the total distance driven to medical care in a 12-month period, which reflects a continuing burden of travel for care. Further, such studies examining healthcare access do not only focus on those with chronic conditions who may need frequent medical services13, or focus on those eligible for services offered through the aging services network who may receive community-based interventions14. To address these gaps, the primary purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with the travel distance to medical care providers among middle-aged and older adults with chronic health conditions. Secondarily, this study aimed to assess utilization of community-based health programs as related to participants’ residential rurality and distance traveled to medical care providers. Because long travel distances to medical care are believed to be an important barrier to healthcare access, it was hypothesized that longer travel distance to formal medical care providers would encourage attendance in community-based programs to prevent/manage chronic illness that are offered closer to home (eg hosted in senior centers, libraries, faith-based organizations)14.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Data gathered for the 2013 Regional Healthcare Partnership Community Health Needs Assessment of Region 17 were used for this study. Region 17 includes nine counties from central Texas: Brazos, Burleson, Grimes, Leon, Madison, Montgomery, Robertson, Walker, and Washington. Thirty-six thousand households were invited to participate in the study via a mailed recruitment letter. A total of 24 768 households were reached in a follow-up call (68.8% contact rate), with 12 177 of those agreeing to complete the survey in either English or Spanish (33.8% agreement rate). Finally, 5320 of the 12 177 who agreed to participate returned surveys, for a return rate of 42.9% (ie 14.8% overall response rate).

Of the 5089 participants with complete data, the following cases were excluded as they did not meet the study’s purposes: participants younger than 51 (n=1201), those without a chronic condition (n=384), those traveling to a doctor from a location other than their home (n=337), those with no routine doctor’s visit in the past year (n=500), and those not reporting the exact number of doctor’s visits in the previous 12 months (n=307). Of the remaining 2360 participants, the authors omitted those with missing data on the variables of interest, including education (n=22), marital status (n=5), number of people living in the household (n=61), healthcare access (n=38), days of poor physical/mental health (n=93), total distance traveled for medical services (n=83), and attending a program to prevent/manage chronic illness (n=13). Some cases had missing data for more than one of these variables. The final analytic sample was 2108 adults aged 51 years and older with one or more chronic conditions who visited a healthcare professional one or more times in the previous year originating from home.

County-by-county comparisons were made between the study sample and the nine-county study region using US Census data. The proportion of study participants from each sample mirrored the county population size and county rurality. The study sample was comparable to the county characteristics in terms of education. Slight variations were noted, with the study sample having modestly smaller household sizes and greater proportions of females and white individuals. These subtle differences may be attributed to the study inclusion criteria.

Measures

Dependent variables: Two dependent variables were included in this study. The first dependent variable was the distance traveled for medical services in the previous 12 months. This variable was constructed from two separate questions. First, participants were asked, ‘In the past 12 months, how many times did you use the following for your own healthcare? Doctor’s office or clinic (all types of medical care).’ This variable was open-ended, and participants could write in the number of visits they attended in the past year. Then, participants were asked, ‘Thinking about where you go for medical care, please tell us how far you travel to get there.’ This variable was open-ended, and participants could write in the distance they travel to get to their medical care (one-way). This value was multiplied by two to obtain the distance traveled to medical care (round-trip). Then, distance (round-trip) was multiplied by the number of doctor’s office visits reported for the previous 12 months. This final value represented the total distance traveled to medical care in the previous year. This variable was trichotomized into statistical tertiles for analysis purposes. The second dependent variable was whether or not participants ever attended a program to help them prevent or manage a chronic illness. Response choices for this dependent variable were ‘no’ and ‘yes’.

Residential rurality Participants’ county of residence were coded based on Rural–Urban Continuum Codes (RUCCs). Each of the nine counties in this region were coded as urban or rural15,16.

Health status Participants were also asked, ‘Has a medical care provider (physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant) ever told you that you had any of the following health problems?’ Participants were asked to self-report their chronic conditions from a list of 16 health problems (scored ‘no’/‘yes’). Examples of health conditions included hypertension, congestive heart failure, diabetes, cancer, asthma, arthritis and depression. All items each participant endorsed were summed to create a continuous variable (range 1–11 conditions). Participants were also asked to complete two open-ended items from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Healthy Days Scale17. The first question was, ‘Now thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?’ Responses could range from 0 days to 30 days17. The second question was, ‘Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?’ Responses could also range from 0 days to 30 days. These items were summed and recoded to create a single variable ranging from 0 days to 30 days indicating the number of days the participant reported physical and/or mental health being not good. Participants were asked, ‘Are you limited in any way in any activities because of any impairment or health problem?’ Response choices were ‘no’ and ‘yes’. Then, participants were asked to rate their perceptions about the following statement: ‘Your access to healthcare whenever you need it.’ Responses were scored using a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘very poor’ (scored 1) to ‘excellent’ (scored 6). This variable was treated continuously in analyses.

Personal characteristics The following participant characteristics were examined: age (range 51–96 years), sex (male, female), race (white, non-white), education (high school or less, more than high school), and marital status (married, unmarried). Participants were also asked to report the number of people who reside with them in their household, including themselves (range 1–8 people).

Statistical analyses: The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v24 was used to perform all analyses (IBM, https://www.ibm.com/analytics/us/en/spss/spss-statistics-version/. The authors first calculated frequencies and descriptive statistics for all variables of interest and then compared them across the two dependent variable categories. We used χ2 tests to measure the differences in distribution for all categorical variables. Independent sample t-tests and one-way ANOVA were run to assess the differences in mean for continuous and count variables. An ordinal regression model was used to assess factors associated with traveling further distances (in miles) to medical services in the past 12 months (ie tertiles from shortest distance to longest distance). A binary logistic regression model was fitted to examine factors associated with attending a program to prevent/manage chronic illness. In this case, not attending a program to prevent/manage chronic illness served as the referent group. For all analyses, statistical analysis was determined at an alpha level of less than 0.05. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were also determined.

Ethics approval

The University of Georgia provided institutional review board approval for this secondary data analysis (#00004540).

Results

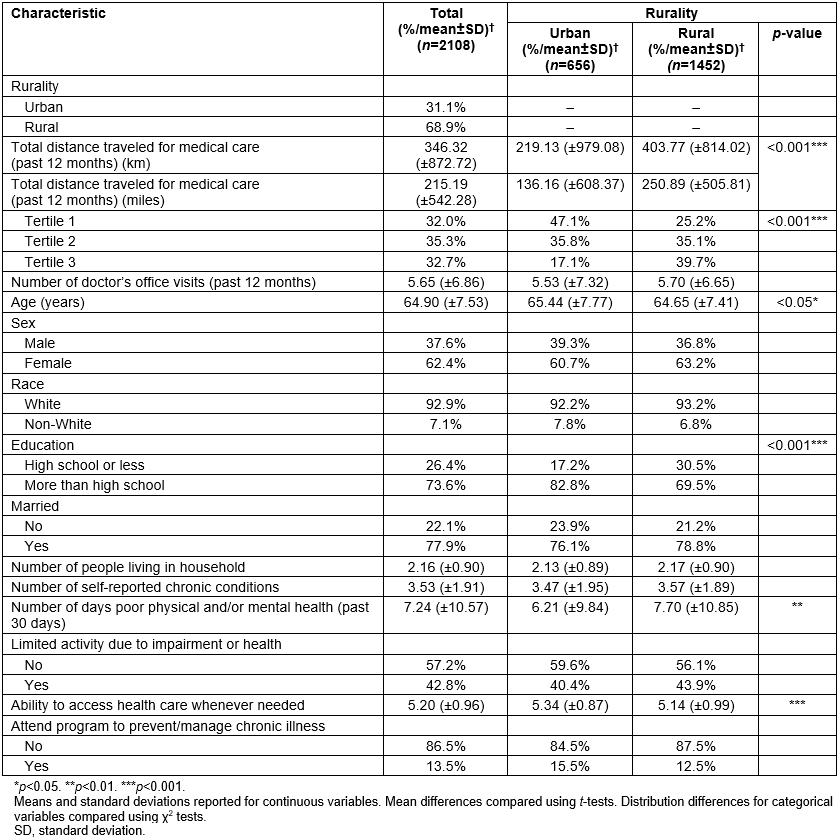

Table 1 presents sample characteristics by rurality. Overall, approximately 69% of participants resided in a rural county. On average, participants had 5.65 (standard deviation (SD): ±6.86) doctor’s office visits and traveled 346.32 (±872.72) km (215.19 (±542.28) mi) for medical care in the previous 12 months. The average age of participants was 64.90 (±7.53) years, and the majority of participants were female (62.4%), white (92.9%), married (77.9%), and had more than a high school education (73.6%). On average, participants self-reported 3.53 (±1.91) chronic conditions and 7.24 (±10.57) days of poor physical/mental health. Approximately 43% of participants reported they experienced limited activity due to their impairment or health problem, and 13.5% reported having attended a program to prevent or manage a chronic illness. When comparing participant characteristics by whether or not the participant resided in a rural county, a significantly larger proportion of participants with a high school education or less resided in a rural county. On average, participants residing in a rural county were younger, traveled further to medical services in the past year, had more days of poor physical/mental health, and lower ability to access health care when needed.

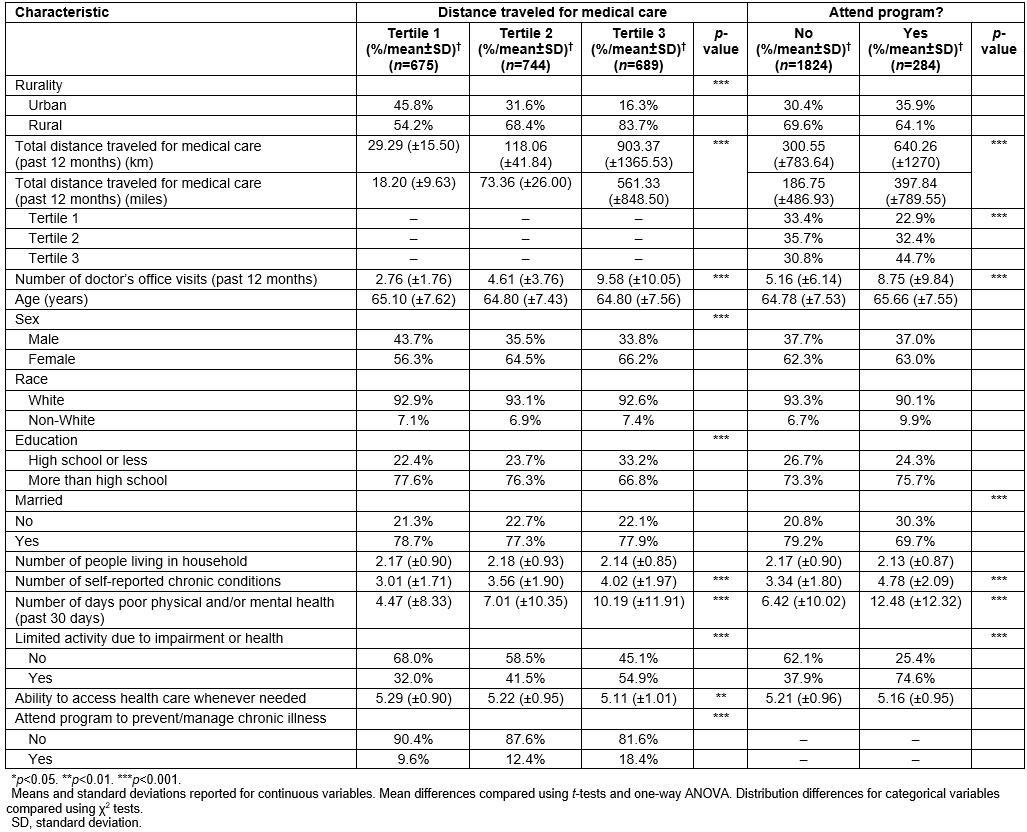

Table 2 presents sample characteristics by the two dependent variables. When comparing participant characteristics by total distance traveled for medical care in the previous 12 months (by tertile), significantly larger proportions of those in a rural county, females, those with a high school education or less, and those with limited activity traveled further for medical care. On average, participants with more chronic conditions, more days of poor physical/mental health, and less ability to access health care when needed traveled further for medical care. When comparing participant characteristics by whether or not the participant attended a program to prevent/manage a chronic illness, those who attended a program traveled significantly further in total to medical care in the previous 12 months. On average, those who attended a program reported more doctor’s visits in the previous 12 months, more self-reported chronic conditions, and more days of poor physical/mental health.

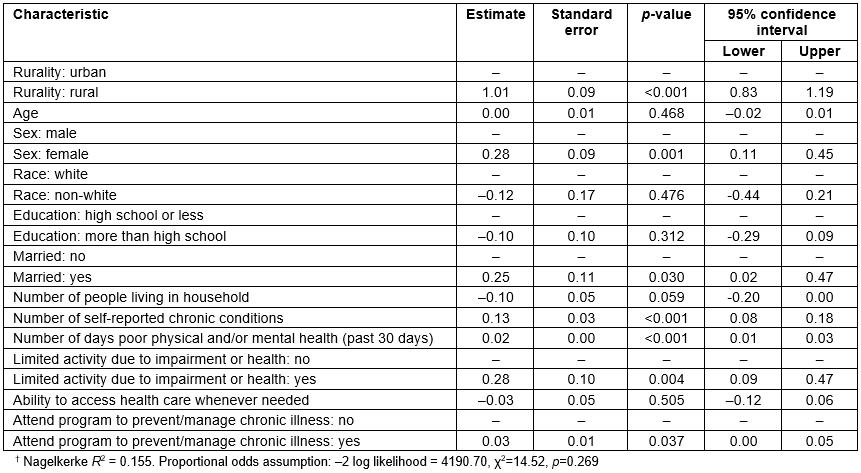

Table 3 presents findings from an ordinal regression model examining factors associated with further travel to medical services in the previous 12 months. Across tertiles, participants residing in rural areas (β=1.01, p<0.001), females (β=0.28, p=0.001), and those who were married (β=0.11, p=0.030) reported traveling further distances to medical services in the previous 12 months. Participants with more self-reported chronic conditions (β=0.13, p<0.001) and those reporting more days of poor physical/mental health (β=0.02, p<0.001) reported traveling further distances to medical services in the previous 12 months. Across tertiles, participants with limited activity due to impairment or health problems (β=0.28, p=0.004) and those who attended a program to prevent/manage chronic illness (β=0.03, p=0.037) reported traveling further distances to medical services in the previous 12 months.

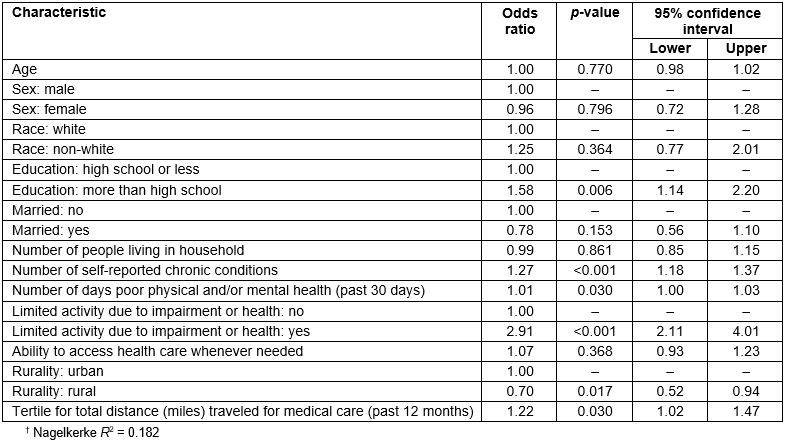

Table 4 presents findings from a logistic regression model examining factors associated with attending a program to prevent or manage chronic illness. Compared to those with a high school education or less, participants with more than a high school education were more likely to attend a program to prevent/manage chronic illness (OR=1.14, p=0.006). For each additional self-reported chronic disease diagnosis, the odds of attending a program to prevent/manage chronic illness significantly increased (OR=1.27, p<0.001). For each additional day of poor physical/mental health in the previous month, the odds of attending a program to prevent/manage chronic illness significantly increased (OR=1.01, p=0.030). Compared to those without limited activity due to impairment or health problems, participants with limited activity were more likely to attend a program to prevent/manage chronic illness (OR=2.91, p<0.001). Compared to those residing in urban counties, participants residing in rural counties were less likely to attend a program to prevent/manage chronic illness (OR=0.70, p=0.017). For every tertile increase in total distance traveled for medical care in the previous 12 months, the odds of attending a program to prevent/manage chronic illness significantly increased (OR=1.22, p=0.030).

Table 1: Sample characteristics by rurality

Table 2: Sample characteristics by dependent variables

Table 3: Factors associated with further travel to medical services (previous 12 months)†

Table 4: Factors associated with attending a program to prevent or manage chronic illness†

Discussion

Findings confirm that rural disparities persist in this sample as related to education, healthcare access, and travel to medical care. This highlights the need to identify available services and resources in the community and link residents to them. If they are not present, they should be strategically introduced to ensure a shorter commute to reach them. An estimated 3.6 million Americans are unable to access necessary medical treatment due to lack of transportation18, and often those missed appointments can result in the use of more costly services down the road18,19. Bolstering non-emergency medical transportation has proven to have significant potential for cost savings20,21. Existing infrastructure (eg transportation services) should be capitalized upon22,23. In addition, a focus on health-related services outside traditional medical care, such as evidence-based programs focused on chronic disease management and/or physical activity, may also hold promise for improving older adults’ ability to successfully age in place, especially for older adults residing in rural areas22,24. While it is intuitive that those traveling further distances for medical care each year reside in rural areas, this measure may also be indicative of those traveling more because of being in worse health. More specifically, those traveling greater distances had, on average, more doctor’s appointments, had more self-reported chronic conditions, more days of poor physical/mental health, and more activity limitations. Part of this issue is that sicker people, who must travel further distances, are more prone to missed visits and health complications, highlighting the value of having alternative services closer to home, including online services and technology25,26. Those who had to travel further distances were more likely to attend programs that focus on education, prevention, and stress management to mitigate the impact of chronic health conditions. People attending programs were in worse health, thus indicating that they are serving those who need them; these sicker individuals travel more. The programs were reaching those in urban areas more than rural areas, which may indicate limited program availability in less population-dense areas (again supporting that the distance traveled is about illness, not just rurality).

Residents of rural areas traveled longer distances, had lower access to health care, were older, and had more days of poor physical/mental health. This can represent several layers of limited access to necessary care among potentially vulnerable individuals with poorer health. Rural areas typically have further distances to travel, yet in this case further distance to healthcare providers may have increased the utilization of other community-based resources. This is similar to past research highlighting further distances traveled for medical care by residents of rural areas27. What did remain was that those in rural areas were less likely to attend a program that may help them better manage their chronic conditions. Potentially because the travel burden is so high in rural areas, individuals with the need to conserve resources may have difficulty reconciling the payoff between seeking medical services for immediate needs compared to the value of prevention, education, and management. Thus, rural health disparities in access and utilization of healthcare services, namely attending a program to prevent or manage chronic illness, is a major issue22. Targeting rural areas with programs to prevent or manage chronic illness may help serve a critical function for at-risk individuals with chronic conditions. Previous research has documented the reach of chronic disease self-management programs to rural areas, and while these programs are reaching rural residents, much more in the way of widespread dissemination and implementation is needed22,28. Policies that target funding for outreach to rural residents are needed to support the aging services sector to deliver programs to rural residents22,24.

Using telehealth, including web-based applications and videoconference technology, is an important consideration for reaching rural areas and has demonstrated success in previous applications25,26. Increased attention to improving connectivity infrastructure in the rural areas must happen simultaneously to the promotion of distance programs, to ensure maximum reach. Telehealth may also alleviate the burden for those in urban areas who have more health-related needs and travel more and longer distances to receive health care. At this time, the digital divide can make offering services to a mobile device or other in-home methods difficult in some rural areas due to slow or non-existent high speed internet connectivity29,30. Less than half of rural residents have access to high-speed internet compared to 92% of urban residents31. Typically, the areas of greatest population density in a rural area are the first to be served with high-speed internet. Therefore, hub and spoke models of telehealth, where individuals can access services at a location closer to home, can improve access to care, reduce travel burden, and work within current limitations of slow connectivity are likely a good fit for evidence-based prevention programs32.

Limitations

This study was cross-sectional in nature and does not measure change over time. As such causality is not implied, but associations with the study outcomes and independent variables are suggested. Further, surveys rely on self-reported data and as such may be affected by recall bias and social desirability. Further, the generalizability of the findings may be limited given the scope of the study is restricted to a single nine-county Texas region, just a small portion of the 254 counties in Texas and an even smaller portion of the more than 3000 counties in the USA. As with much research, this study focused on key outcomes and as such that focus on variables of interest reduced the possible representativeness of the sample (omitting certain cases from analyses). While the county-specific county sub-groups mostly represented the county demographics, differences may have been attributed to the sample being purposively limited to individuals aged 51 years and older with one or more chronic conditions who visited a healthcare professional one or more times in the previous year, originating from home. Because county-specific estimates are not available with this level of specificity, the exact representativeness of the sample to each county is unknown.

Information about the general medical visits and purposes for each visit was not available. Such information may shed further insight into reasons individuals are seeking care (eg treatment for preventable complications versus routine visits). In line with this, there is no information regarding other trips that were related to medical care including visits to the pharmacy to fill medications, going to the dentist, rehabilitation, or seeking care for vision-related medical services. Also, there was no information available about the use of in-home health services, such as rehabilitation or skilled nursing, which may reduce or increase travel distance to health care. When considering responses for attending a program to prevent or manage chronic illness, there was no information about what specific program they attended, how many times they came to the program, or any related outcomes. Thus, it is recommended that more research be conducted to further investigate what programs individuals are attending and what programs are reaching particularly at-risk individuals.

Additionally, in the current study, tertiles to describe distance traveled to health care were calculated for the entire study, then compared by rurality. To further understand the context of travel distance and rurality, future studies should examine factors associated with healthcare travel and program attendance after creating rurality-specific tertiles (separately for rural and urban).

Conclusion

This study highlights the complexity in access to medical care for middle-aged and older adults. The existing literature may underrepresent the true travel burden in rural and urban areas by neglecting to account for the number of round trips taken in a given period, especially for those with complex, comorbid health conditions. Several policy-relevant issues that can be targeted, including building and maintaining adequate healthcare infrastructure; building, expanding, and maintaining a non-emergency transportation infrastructure, especially in rural areas; encouraging collaborative efforts between urban health professionals and rural/regional providers; and ensuring adequate delivery of evidence-based programs (non-clinical in nature) to particularly at-risk individuals. Further research can provide insight into the success of these potential policy actions in ameliorating gaps in access to care for the millions of older adults throughout the USA.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Center for Community Health Development under the Cooperative Agreement Number 1U48 DP001924 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion and the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2013 - Multiple mini-interview scores of medical school applicants with and without rural attributes