Introduction

Gout is a common inflammatory arthritis and males have higher prevalence than females1. Gouty arthropathy is a joint disease caused by the formation of uric acid crystals in a joint space. The prevalence of gout has been increasing yearly in Maori and European populations2. In Taiwan, the prevalence of gout increased between 1993–1996 and 2005–2008 (4.7% v 8.2% in men and 2.2% v 2.3% in women)3. The prevalence of gout is 11.7% in Taiwanese aborigines4.

Monoamine oxidase A enzyme activity is associated with risk of gout. Monoamine oxidase plays a major role in renal dopamine metabolic pathways, which influence uric acid level and urate excretion by controlling dopamine-induced glomerular filtration response. The mechanism may explain the higher prevalence of gout in Taiwanese aborigines5.

An Australian study reported an increased rate of urinary stones in aboriginal children, especially those living in remote and arid areas6. In Taiwan, the prevalence of upper urinary calculi is 9.6% (14.5% in men and 4.3% in women)7. Due to a defect in the renal production of ammonia, patients with gout have acidic urine and are prone to urate crystal deposition8. Some risk factors such as alcohol consumption9 may increase gout formation.

There are 16 aboriginal groups in Taiwan. The Atayal and Bunun, as the majority aboriginal groups in the present study, are the third and fourth largest populations of aborigines in Taiwan. The ethnic differences in ureterorenal stone appearance after gouty arthropathy remain unknown. This study investigated the differences in ureterorenal stone appearance after gouty arthropathy between aboriginal and non-aboriginal Taiwanese patients.

Methods

Patients presenting to Puli Christian Hospital between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2015 with a first diagnosis of ureterorenal stones after diagnosis of gouty arthropathy were enrolled in this study. This is a retrospective cohort study reviewing medical records and using the code of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The study hospital is located in the mountainous area of central Taiwan, which is populated by many aboriginal tribes. According to the Household Registration Service of Nantou Country (2018), the population in the area of Puli, Renai and Xinyi is approximately 112 500. Among this population, approximately 26 000 are aboriginal Taiwanese, mostly Atayal and Bunun people.

The ethnicity, age, sex, location of stone and time until stone appearance after gouty arthropathy were recorded from the electronic medical records. Underlying diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and hepatitis (alcoholic or non-alcoholic) were included. The authors also analysed serum levels of uric acid, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) when gouty arthropathy was diagnosed. Urine pH was recorded when the ureterorenal stones were diagnosed.

A χ2 test was used to compare differences in ethnicity, sex, location of stone and underlying diseases between aboriginal and non-aboriginal patients. A t-test was used to examine the age, time until stone appearance, serum levels of uric acid, creatinine, BUN, eGFR and urine pH.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Puli Christian Hospital (PCH-EC-2015-01).

Results

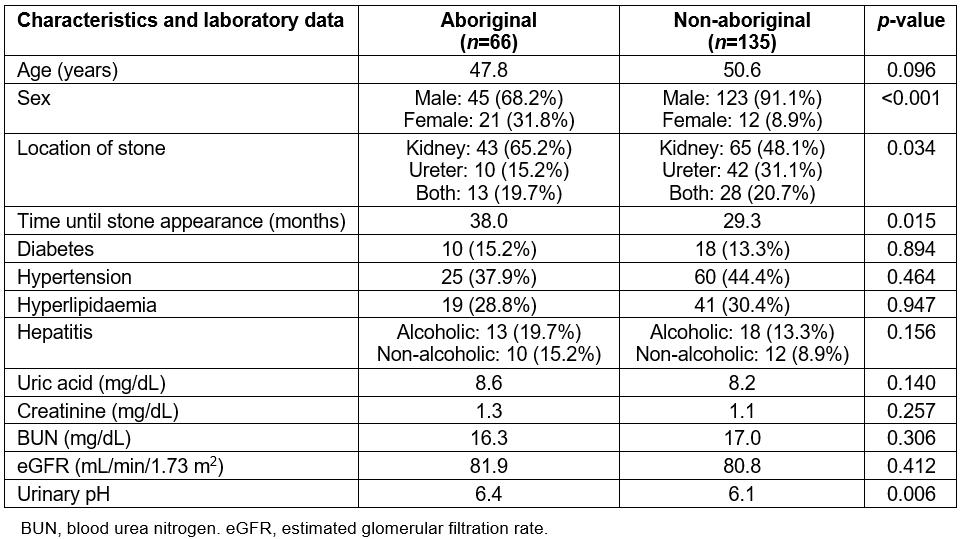

Between 2007 and 2015, 201 patients (66 aboriginal and 135 non-aboriginal) with a first diagnosis of ureterorenal stones after gouty arthropathy were enrolled in the study. The patients’ characteristics, underlying diseases and laboratory data are shown in Table 1. The aboriginal group demonstrated a higher female-to-male ratio (0.47 v 0.10, p<0.001) and renal stone percentage (65.2% v 48.1%, p=0.034) compared with the non-aboriginal group. The aboriginal patients also exhibited longer times until stone appearance after gouty arthropathy (38.0 v 29.3 months, p=0.015) and had urine that was more alkaline (pH 6.4 v 6.1, p=0.006) when ureterorenal stones were diagnosed. No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding age, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and alcoholic hepatitis. Laboratory data such as uric acid, creatinine, eGFR and BUN revealed no differences between the two groups.

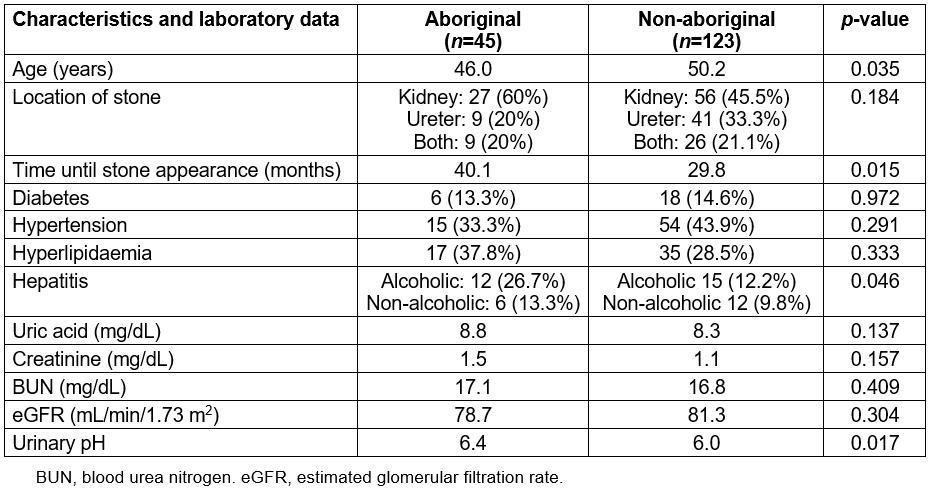

Among the males, 45 were aboriginal and 123 were non-aboriginal. The patients’ characteristics, underlying diseases and laboratory data are shown in Table 2. The aboriginal patients exhibited gouty arthropathy at a younger age than non-aboriginal patients (46.0 v 50.2 years, p=0.035), and they displayed a higher rate of alcoholic hepatitis (26.7% v 12.2%, p=0.046). The aboriginal group also exhibited longer times until stone appearance after gouty arthropathy (40.1 v 29.8 months, p=0.015) and had urine that was more alkaline (pH 6.4 v 6.0, p=0.017) when the ureterorenal stones were diagnosed.

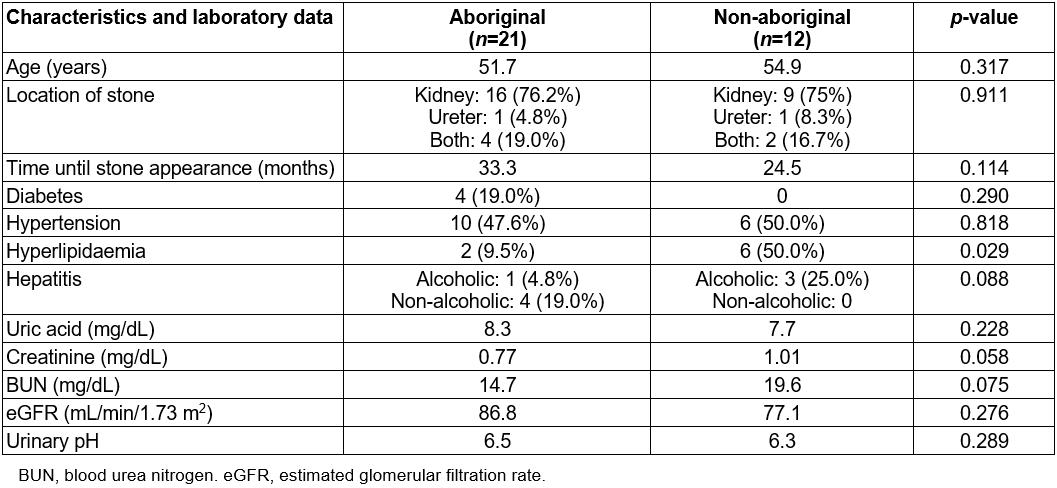

Among the females, 21 were aboriginal and 12 were non-aboriginal. The patients’ characteristics, underlying diseases and laboratory data are shown in Table 3. Hyperlipidaemia was significantly higher in non-aboriginal patients (9.5% v 50.0%, p=0.029).

Table 1: Patient characteristics, underlying diseases and laboratory data

Table 2: Male patient characteristics, underlying diseases and laboratory data

Table 3: Female patient characteristics, underlying diseases and laboratory data

Discussion

Risk factors for gouty arthropathy and ureterorenal stones are related to lifestyle and social habit10, supporting differences observed between aboriginal and non-aboriginal patients. In this study, the authors identified ethnic differences in ureterorenal stones after gouty arthropathy. It was found that the aboriginal patients exhibited a longer time until stone appearance after gouty arthropathy, and male aboriginal patients developed gouty arthropathy at younger ages than did male non-aboriginal patients.

Age and sex

A study of gout attacks demonstrated that identifiable triggers are more common in those with early-onset gout11. Males are predisposed to an earlier age of gout onset, which is linked to obesity12. Due to female sex hormones, women are protected against gout in the pre-menopausal period. Therefore, men outnumbered women in all age groups for gout prevalence, more in younger than older age groups, by ratios of 10:1 and 5:1, respectively13. The sex difference is less pronounced with increasing age, but men still outnumber women with gout, even among older adults.

The incidence of urolithiasis has increased worldwide. A study evaluating metabolic risk factors for urolithiasis revealed that hyperoxaluria, hyperuricosuria and hypocitraturia are more common in men than in women; moreover, hypercalciuria is more common in patients younger than 60 years14. Metabolic profiles are also observed in different sex and age groups. Men and younger patients have higher lithogenic risks compared with women and older patients. Younger women have lower risk of stone formation, which is attributed to diet and fluid intake.

Alcohol

Alcohol, which is made from fermented grains, plays a vital role in gout. Alcohol decreases kidney uratic acid excretion and increases urate production. Thus, alcohol increases serum uric acid concentration, and it exacerbates and induces gout attacks. Alcohol consumption, especially of beer and hard liquor, increases the incidence of gout15. One study evaluated the effects of quantity and type (beer or wine) of alcohol consumed on the risk of gout attacks. Alcohol consumption, regardless of the type of alcoholic beverage, was associated with an increased risk of gout attacks, even for moderate amounts of alcohol16. In particular, young-onset gout was related to excessive alcohol consumption11. Therefore, individuals with gout should limit alcohol consumption to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

Alcohol acts as a diuretic. The rate of urolithiasis decreases by 10% with an increase of 10 g/day of alcohol consumption17. In the present study, the male aboriginal patients exhibited a longer time until stone formation after gouty arthropathy; this can be attributed to diuresis because of higher prevalence of alcoholic hepatitis. So, decreasing the alcohol consumption will prevent the formation of gouty arthropathy.

Hypertension

Hypertension is associated with a higher incidence of gout15. A recent study strongly supported this association and indicated that the use of diuretics to treat hypertension can induce gout18. Loop diuretics and thiazide were associated with higher risks of gout15. The mechanism of diuretic-induced hyperuricaemia can cause the creation of diuretics; losartan is used to treat hypertensive patients with gout, and possesses mild diuretic properties18.

Diabetes

Diabetes is associated with a higher risk of gout15. Serum uric acid concentration is strongly related to type 2 diabetes, and severe insulin resistance and renal impairment exacerbate gout severity19. Another study, however, revealed that individuals with diabetes are at lower risk of gout, independent of other risk factors. The mechanism was attributed to the uricosuric effect of glycosuria and the impaired inflammatory response20. A Taiwanese study revealed that patients with diabetes treated with pioglitazone exhibited a lower incidence of gout21. By inhibiting the expression of tumour necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ, pioglitazone has anti-inflammatory effects.

An increased prevalence of stone formation has been reported in patients with diabetes. Oral hypoglycaemic agents (such as biguanides) can influence urine properties and induce stone formation22. Diabetes results in lower urine pH through renal impairment and uric acid stone formation23.

Hyperlipidaemia

Hypertriglyceridaemia is associated with a risk of gout24. Hypertriglyceridaemia, especially in men, may promote gout development through its effect on serum uric acid24. According to the vascular aetiology of stone formation, dyslipidaemia theoretically predisposes patients to nephrolithiasis. One study demonstrated that dyslipidaemia is associated with an increased risk of stone disease; the only specific lipid panel associated with lower nephrolithiasis is high-density lipoprotein25. In the present study, the hyperlipidaemia rate was no different between aboriginal and non-aboriginal patients.

Renal function, serum uric acid and urinary pH

Renal impairment can induce and exacerbate gout attacks19. Nishida demonstrated that urinary creatinine and uric acid excretion in patients with gout were significantly increased when compared with people without gout; increased creatinine synthesis was determined to accelerate uric acid synthesis26. Thus, renal impairment may induce and exacerbate gout attacks. Hyperuricaemia can also cause renal damage, and there is increasing evidence of a correlation between urate-lowering therapy and renal morbidity27. Therefore, early treatment of hyperuricaemia is strongly recommended to prevent chronic kidney disease.

Urinary pH is a primary determinant of ureterorenal stone formation. Alkaline pH favours the crystallisation of calcium- and phosphate-containing stones28. In the present study, aboriginal patients exhibited more-alkaline urine than did non-aboriginal patients, but there were no differences in serum uric acid levels. This can be attributed to early medical treatment after diagnosis.

Limitations

This retrospective study identified the ethnic differences in ureterorenal stones after gouty arthropathy. However, the present study had several limitations. First, gouty arthropathy was diagnosed by individual physicians, thus it was not possible to determine whether diagnoses were confirmed subjectively through clinical impression or objectively by joint aspiration or imaging. However, the National Health Insurance in Taiwan ensures that all insurance claims are scrutinised by medical reimbursement specialists. Therefore, the diagnoses of gouty arthropathy in this study were highly reliable. Similarly, the diagnoses of ureterorenal stones were also reliable, regardless of the specialist’s diagnostic method (X-ray imaging or ultrasound). Second, patients with ureterorenal stones can exhibit no clinical symptoms. The authors may have underestimated the incidence of stones after gouty arthropathy. Third, some patients’ characteristics, such as lifestyle and dietary information, were not available in this study. These factors could influence the incidences of gouty arthropathy and ureterorenal stones. Despite several limitations, this study accurately reflects the situation in this area of Taiwan.

Conclusion

Among males, aboriginal Taiwanese patients in this study exhibited gouty arthropathy at younger ages than did non-aboriginal Taiwanese because of a higher rate of alcoholic hepatitis. The longer time until stone appearance after gouty arthropathy was attributed to alcoholic diuresis. Decreasing alcohol consumption may postpone or halt the development of gouty arthropathy.