Dear Editor

Historically, recruitment and retention of female doctors in rural and remote areas has been a challenge in many developed jurisdictions. In the Australian context, there remains an acute shortage of female general practitioners (GPs) in rural and remote areas1. Poor access to female GPs is related to poorer health outcomes and health services use among women1. Yet, while studies have investigated overall GP mobility in Australia2, none have specifically investigated the mobility of female GPs nationally.

Publicly available individual level data (obtained through a special data request) from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) on all doctors that AHPRA registers as specialists in general practice represents an almost complete census of GPs. Data for 2011 were linked with 2014 using full names and registration numbers. Postcodes of GP principal place of practice (PPP) were linked to Australian Statistical Geographic Standard rurality and remoteness categories to infer mobility across rurality categories. GPs whose PPP postcodes changed between 2011 and 2014 were deemed to have moved geographically. The final dataset comprised 21 894 GPs in 2011 (8560 female and 13 334 male).

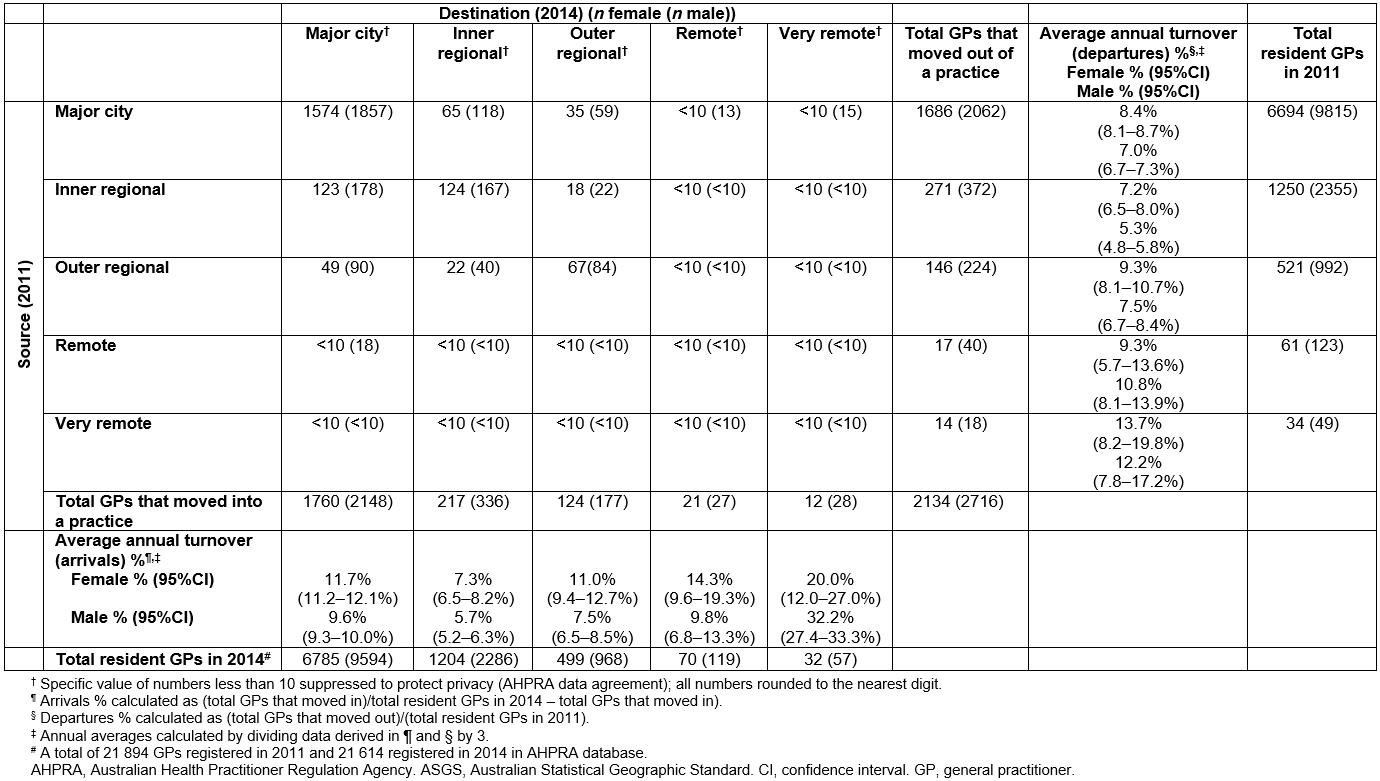

Examining those GPs who moved practices between 2011 and 2014 (not counting those commencing or leaving practice as movers) overall around 7.4% (95% confidence interval (CI): 7.2 7.6%) of all GPs left their PPP annually (Table 1). Significantly more female GPs (8.4%; 95%CI: 8.0–8.6%)) moved out of their practice annually than male GPs (6.8%; 95%CI: 6.6–7.0%)). Female GPs had significantly greater departure rates in major city and regional (inner and outer) areas than male GPs, ranging between 8% and 9% annually (Table 1). These departure rates were compensated by significantly greater arrival rates among female GPs. A drift out of non-metropolitan areas existed for all GPs. Thus, over the 3-year period 112 female GPs and 205 male GPs moved out of major city areas into more rural areas. In contrast, 186 female GPs and 291 male GPs moved in the opposite direction. Nevertheless, cities remained the largest source and destination of GPs going to and coming from other areas, and most moves were within remoteness categories. Remote/very remote areas show very high rates of movement, which could be real or a statistical artefact from the very small numbers of GPs in these areas, or a combination of these effects.

Researchers have reported female GPs intend to stay in their current practice for significantly less time than male GPs3. Higher mobility among female GPs may have familial drivers, such as an intention to accompany a spouse to other locations4 or schooling for children, in addition to the usual motivations for moving, such as access to better professional support and services5. While the present results represent movement rates in the 2011–2014 period, ongoing changes in GP training, and especially the embedding of rural placements in GP training, could in time affect the distribution and retention patterns of female GPs6. Limitations of this study include the exclusion of all doctors other than specialist GP registrants (eg registrars or interns), the use of head counts instead of workload, and the relatively short period covered by the study (3 years).

Acknowledgements

This research was initiated at the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute, which was a key component of the Australian Government funded Primary Health Care Research, Evaluation and Development (2000–2014) strategy. We are grateful to the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency for providing the data.

Soumya Mazumdar, NSW Health, University of New South Wales

Ian Mcrae, Australian National University

Table 1: Numbers of female and male GPs moving practice within and across Australian Statistical Geographic Standard Rurality and Remoteness area categories between 2011 and 2014.