Introduction

There have long been geographic maldistributions of healthcare professionals, which contribute to the health disparities experienced by rural peoples worldwide1-4. This is particularly evident in countries such as Canada, where about 95% of the geography is rural5. While some 16.8% of the population of Canada lives in a rural environment, their health needs are served by only 8.2% of physicians6. This disparity is similarly observed in other countries and in other healthcare fields2. Current evidence suggests students with a rural origin and students trained in a rural context are more likely to consider rural health careers7-16 yet rural candidates are underrepresented at medical schools, most of which are urban based7,17. Efforts to deal with this maldistribution have led to the creation of a number of different models of distributed medical education, which collectively strive to increase the number of students training and practicing in rural locations18-20. Students of rural origin face many barriers not shared with their urban counterparts in attaining admission to healthcare training9,17. They are less likely to pursue post-secondary education and may be disproportionately underrepresented in health-related programs21. Rural youth are less likely to believe that they could gain admission to medical school and may also be relatively unaware of career options in health care, compared to their urban counterparts22.

Many different initiatives exist within the spectrum of rural healthcare pipeline programs23,24. University–high school outreach programs are at the earliest stage of the pipeline, and there remains a relative paucity of initiatives that visit youth in their rural communities9. Some of the initiatives described previously include a Mini-Med School program that focused on interactive stations delivered by experienced clinician educators25, a Mini-Med School focused on Indigenous youth, with interactive stations facilitated by medical students26, a rural secondary school outreach program with both lectures and interactive stations facilitated by medical students27, and a high school outreach for nursing student recruitment where practicing nurses, educators, and administrators provided information on opportunities at various different rural targeted venues12.

The Healthcare Travelling Roadshow (HCTRS) was conceived in 2009 at a rural healthcare workforce symposium held in Prince George, British Columbia (BC), in response to workforce shortages. Rural communities were to provide students with a rich learning context for understanding interprofessional collaboration and rural healthcare opportunities and challenges. The interprofessional healthcare student team was to engage local youth and provide education and encouragement towards healthcare training and careers. Each roadshow was to be customized to the communities and schools to be visited, striving to meet the needs of the region, and involve Indigenous students and healthcare providers wherever possible.

This article reports the outcomes of the program from 2010–2017. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first description of an initiative for rural university–high school healthcare career outreach that involves near-peer teaching, highly interactive sessions, and an interprofessional focus.

Methods

Study design and setting

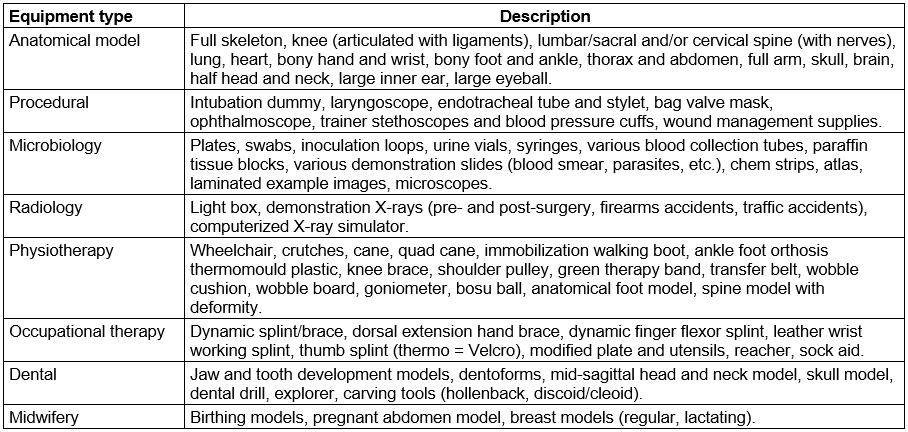

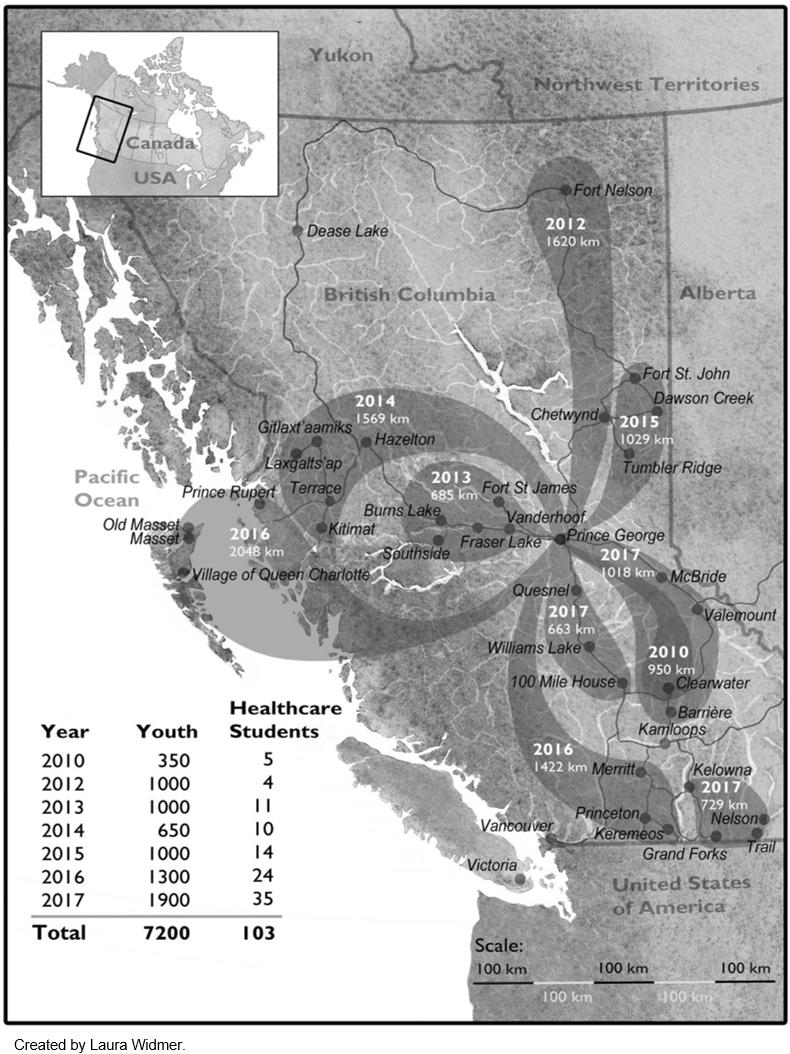

Since 2010, the HCTRS has occurred once or more annually in northern rural and remote BC communities (population ~500–20 000), with presentations at local high schools on different healthcare careers. A typical roadshow consisted of 7 days of travel, visiting three communities and conducting 10 high school presentations (Fig1). Presentations were delivered to all youth within a cohort (typically grade 10, depending on community size and needs). The goals were to:

- showcase healthcare careers as options for rural students

- showcase the rural community as a career option for healthcare students

- provide an interdisciplinary experience for healthcare students.

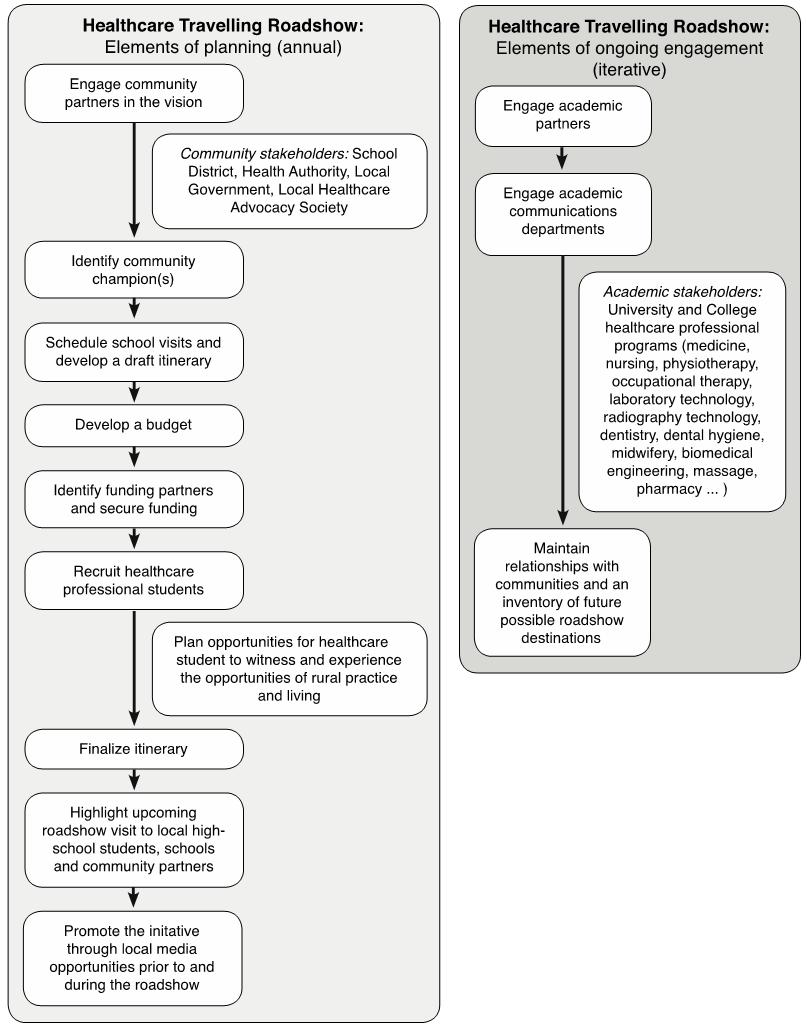

This was to be accomplished through highly interactive presentations, and involve near-peer teaching28,29, using medical equipment similar to that used in everyday healthcare situations (Table 1). A collaborative model was conceived, requiring an academic champion to engage with the academic partners, and work closely with a community champion who engaged with the various community partners to identify the specific needs of the community and how best the HCTRS may be tailored to address those needs during the timeframe of the proposed roadshow and on an ongoing basis (Fig2).

The evaluation used data from both the 2010 pilot and ongoing program evaluation. Qualitative data were analysed using a thematic analysis approach, as described below30.

Table 1: Sample equipment inventory

Figure 1: Summary of healthcare travelling roadshows 2010–2017. Dark bubbles indicate the year of the trip, the total distance travelled, and the communities visited. The years 2010 and 2012–2015 each had one annual trip, 2016 had two, and 2017 saw three annual trips, including the first trip based outside of Prince George.

Figure 1: Summary of healthcare travelling roadshows 2010–2017. Dark bubbles indicate the year of the trip, the total distance travelled, and the communities visited. The years 2010 and 2012–2015 each had one annual trip, 2016 had two, and 2017 saw three annual trips, including the first trip based outside of Prince George.

Figure 2: Elements of planning and ongoing engagement.

Figure 2: Elements of planning and ongoing engagement.

Sampling

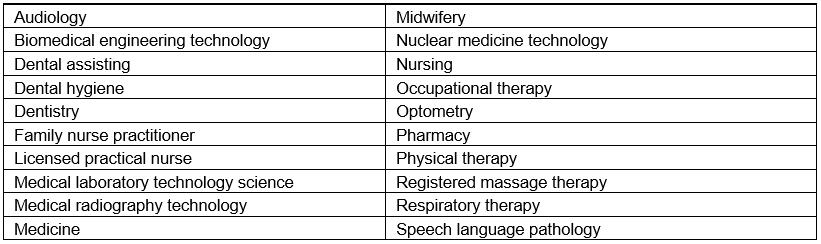

Convenience sampling was utilized both during and immediately after each annual HCTRS trip. Three separate populations were targeted to ensure that the data obtained represented all parties involved. Students registered in healthcare career training programs in the province of BC, at any stage of training, were invited to apply to participate in the HCTRS. Participants were selected based on a combination of criteria including desire to inspire youth to consider healthcare careers, knowledge of or desire to learn about rural health care, and diversity of applicants (careers, training locations, gender, backgrounds). A preference was given to involving new healthcare students on each trip but a few students participated in more than one trip. Students were given minimal guidance on developing their presentations, and commonly the student presentations evolved throughout the trip. In 2010–2017, students were from 20 different healthcare training programs, located in small and large centers across the province (Table 2), with different combinations of careers represented on each trip. Typically, eight different healthcare careers were represented on each trip, and healthcare students were generally in their mid-20s, consistent with a near-peer teaching approach28,29. Key community members (teachers, administrators, hospital staff, town councillors, etc.) were identified based on previous interaction, and then invited, either by email or in person, to submit feedback on their experiences. Healthcare students were invited to provide feedback at the end of their week partaking in the HCTRS. Youth were also asked for feedback, facilitated by their school (2010 only). Participants in the study were youth (high school students; n=22), community members (n=62) and healthcare students (n=57).

Table 2: Careers represented in the healthcare travelling roadshow (2010–2017)

Data collection

The questionnaires developed in the pilot study were designed for three separate populations (youth, community members, and healthcare students) and formed the basis for those used in ongoing program evaluation. The data presented are a composite of both pilot and ongoing program evaluation. Questionnaires contained both quantitative and qualitative elements. Respondents were asked to answer three quantitative questions each on a five-point Likert scale, with healthcare students answering an additional question. Two open-ended narrative questions asked respondents to articulate strengths of the HCTRS and areas for improvement. Data were collected using either paper or electronic forms. These data were transcribed into separate documents based on respondent type and question being asked. These documents were then transferred into NVivo v11 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/home) to facilitate the generation of codes and themes. Data collection occurred between 2010 and 2017, on 10 different trips, resulting in a total of 141 respondents between all three populations. Non-participation was not a concern and specific number of refusals to participate was not tracked.

Analysis

Quantitative data are shown with Likert scale averages and confidence intervals calculated using Microsoft Excel. Qualitative data were coded iteratively by three investigators (SBM, KM and JQG) in NVivo. These codes were then analyzed by a single author (KT) to ensure congruity and comprehensiveness. An inductive approach to coding was used, basing codes on the data and not on any existing framework30. Codes were generated simultaneously for all respondent types and were not separated based on this parameter. Themes were generated through a semantic approach to summarize the data without much interpretation30. Themes that emerged are based on collective data from all respondents across all years.

Ethics approval

A pilot study was conducted with youth in 2010, with both student assent and parental consent for youth to complete the questionnaire and be filmed for promotional film development. Ethics approval was granted by the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board (protocol H10-01345) and the University of Northern British Columbia Research Ethics Board (protocol E2010.0520.089). Program evaluations were conducted with healthcare students and community members from 2010 to 2017, for the primary purpose of program improvement.

Results

Quantitative analysis

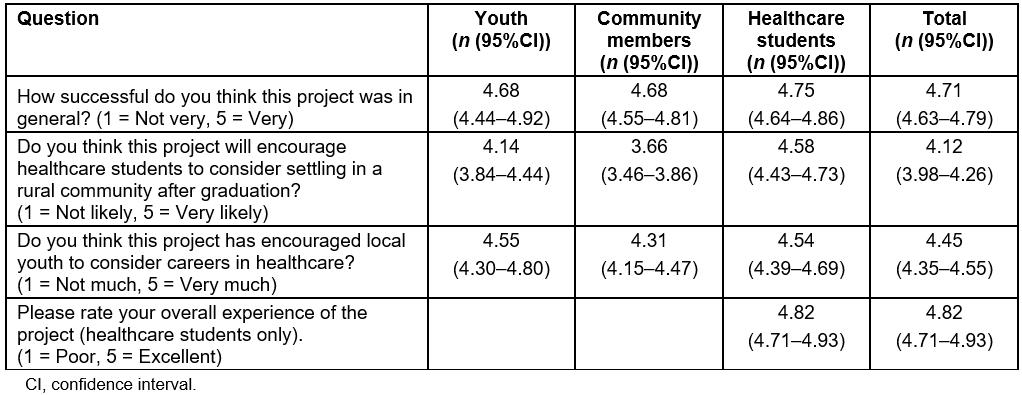

Youth, healthcare students, and community members consistently indicated that the HCTRS was successful or very successful (Table 3). When asked whether they thought this initiative would help encourage healthcare students to consider one day taking up practice in a rural community, youth and healthcare students thought this was likely or very likely, whereas the community members felt this was only somewhat likely to likely. Regarding whether the HCTRS achieved the aim of inspiring local youth to consider careers in health care, all groups felt the HCTRS did this very much. Healthcare students consistently rated the overall experience very highly.

Table 3: Quantitative evaluation of the healthcare travelling roadshow. Average of responses to program evaluation questions, with 95% confidence intervals presented by population: youth (n=22), community members (n=62), healthcare students (n=57), and total (n=141 or n=57 total for question 4)

Qualitative analysis

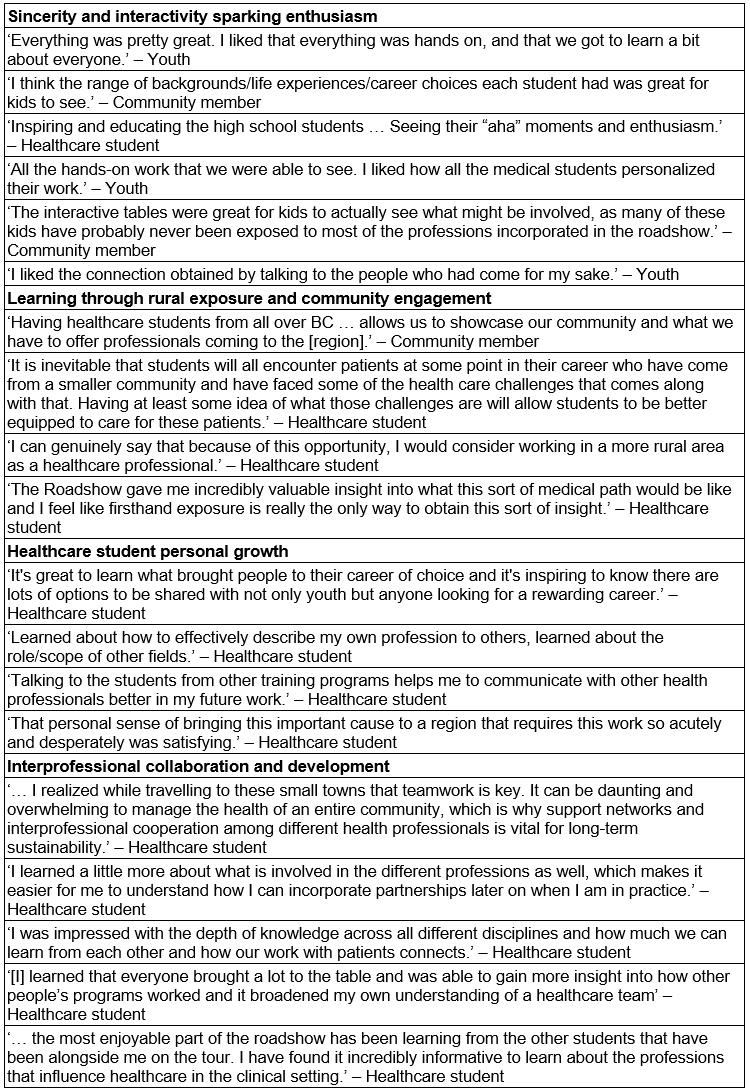

Four major themes arose from the analysis: (1) sincerity and interactivity sparking enthusiasm, (2) learning through rural exposure and community engagement, (3) healthcare student personal growth, and (4) interprofessional collaboration and development. The first two themes arose across all three populations, while the last two arose only with the healthcare students. Quotes representing the variety of perspectives encompassed within each theme are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Highlights of program evaluation. Representative quotes organized by theme

Sincerity and interactivity sparking enthusiasm

This theme was the most prominent across all populations. Nearly all youth valued interactivity when asked their view of the best part of the HCTRS. Healthcare students often commented that they most enjoyed the enthusiasm they were able to elicit from students during the small group presentations. The most common key ideas within this theme included inspiring youth, mentoring through sharing stories, sincerity of the healthcare students, and enjoyment of the interactive stations. The community members also found the presentation of the diversity of healthcare career options to be powerful.

Learning through rural exposure and community engagement

Healthcare students as well as community members viewed rural exposure and community engagement as paramount in the impact of the HCTRS. Healthcare students from both smaller and larger centers often remarked on how the HCTRS opened their eyes to rural life and its benefits as well as its challenges. Some students were profoundly impacted by the resource scarcities in rural towns and how this was managed by the local healthcare teams. Community members often wrote about their positive interactions with the healthcare students during the HCTRS and specifically during tours of community healthcare facilities, when community leaders showcased their communities. Community members were optimistic that, by following such robust engagement with the community, students would be more likely to consider rural practice as a viable career option in the future.

Healthcare student personal growth

A less common but still prominent theme that arose was the personal growth of the healthcare students. This stands out as a major ancillary benefit of the HCTRS beyond achieving its three goals. Students articulated being inspired to be better people, gaining confidence in describing their career to others, and increasing their cultural competency. Personal growth came from the interprofessional interactions, high school presentations, and community exposure.

Interprofessional collaboration and development

The theme of interprofessionalism was unique to the healthcare students. Interprofessionalism was one of the most commonly occurring themes throughout the data, suggesting that the healthcare students regarded this as one of the most impactful aspects of the HCTRS. Students talked mostly about their interactions with the other healthcare students, and how the experience of learning with, from and about each other helped them to develop a better, more holistic understanding of interprofessionalism in health care.

The majority of constructive comments from all three populations were operational recommendations. However, these were largely contradictory. Some wanted larger presentations to include more students; others wanted smaller presentations for more engagement. Some wanted more time for interaction; others wanted more presentations to happen. These paradoxical ideas were represented across populations and illustrate the importance of taking a balanced approach to planning the HCTRS, ensuring the goals of the HCTRS are best met, while meeting the needs of the host communities as much as possible. Finding this balance requires thoughtful planning and communication on the part of the academic and community champions.

Discussion

The present data show that the HCTRS was uniformly well received and largely successful in achieving its goals. Participants mostly rated the success of different aspects of the initiative at greater than 4 out of 5. One notable exception was that community members felt it was only somewhat likely to likely that the HCTRS would encourage healthcare students to consider rural practice. The community members may have had a more realistic perspective, given their lived experience with the realities of rural healthcare recruitment and retention. It is also possible that they may not have understood the full scope of the HCTRS, as few community members were engaged in all aspects (school presentations, community tours, hospital tours, and social events). Additionally, community members may have had a more sceptical perspective than the healthcare students, who were typically two to three decades younger. Community involvement and ‘fit’ is important in rural recruitment for practitioners of both rural and urban background31. Younger healthcare practitioners have different career aspirations than their senior colleagues and working with these different aspirations contributes to success in recruitment and retention6. If community members believe it is unlikely that their youth will go into health care or that the HCTRS students are unlikely to choose rural practice, their attitudes could decrease the success of the initiative. As the HCTRS grows and engages community members in discussion about rural healthcare recruitment, a desirable outcome would be building community optimism about rural healthcare recruitment.

In the qualitative analysis, all three populations articulated that the HCTRS was successful in achieving the three goals set out by the program. Furthermore, all community respondents, when asked whether they hoped the roadshow would return to their community, responded in the affirmative, often emphatically. This illustrates how well the HCTRS was received by communities, and their belief that it may help to address rural healthcare shortages. In addition, through open-ended feedback, novel benefits outside of the three main goals were identified. These include personal growth for healthcare students and positive engagement with the community leaving a lasting impact on their understanding of rural health care. The interprofessional design was a high impact aspect of the HCTRS for the healthcare students. Interprofessional initiatives have many benefits for rural health care at the post-licensure level, including patient care cost savings, and recruitment and retention of healthcare professionals32. Whether interprofessional rural exposure at the trainee level is associated with long term rural recruitment and retention is not currently known32, but is an important area for future HCTRS research.

Constructive feedback illustrates the complexity of trying to meet the diverse needs of the stakeholders. Many details need to be negotiated in the planning of each trip, including number of presentations, presentation size and duration, target grade, nature or extent of community and healthcare facility tours. Meaningful community engagement is key in the planning and execution of the roadshow, as in other areas of rural health sciences education33. Community members shared how speaking to the healthcare students about their community, its strengths and needs, allowed them to showcase their community and shed light on the healthcare disparities specific to their community. Based on the community and academic champions’ suggestions to ensure success, the program needs to continue to tailor its implementation, and be flexible to best address the needs of the various stakeholders involved in each trip.

One of the most common ideas to emerge from the data was that of personal interaction, and the power therein. This was brought up in many different instances, which show how opening a narrative on rural health care between secondary school students, healthcare students, and communities can act to bring about a change in mindset that could see rural healthcare shortages lessen in the future. Secondary school students remarked on how hearing the stories of healthcare students gave them a better understanding of each career and brought realism to the intangible idea of pursuing healthcare in their future careers. Community members shared how speaking to the healthcare students about their community, its strengths and needs, allowed them to showcase their community and shed light on their specific healthcare disparities. Healthcare students spoke often about how amazing it was to share their stories with secondary school students as well as with each other; thereby giving them a framework for how to view themselves and their role within the healthcare team. The HCTRS has worked to open the narrative of healthcare disparities in rural communities, which may help to address this gap in the future.

Limitations

This article describes the evaluation of an innovation to address rural healthcare workforce shortages. The analysis summarizes participants’ impressions at the time of the HCTRS, but cannot infer success in improving rural healthcare workforce recruiting. Further study of the impact of the HCTRS over the long term is warranted.

Conclusions

The barriers to recruiting healthcare professionals to rural regions are multifaceted, thus effective strategies to address this issue must also be multifaceted2,12. Since 2010 the HCTRS has been visiting rural communities throughout BC, with the aim of exposing rural youth to healthcare career options and healthcare students to rural health care and communities. Feedback from key community members, healthcare students and secondary school students has been overwhelmingly positive, indicating that the HCTRS has been successful in achieving its goals. Suggestions for improvement demonstrate the need for taking a balanced approach and tailoring the program to each community. Open-ended feedback identified successes outside of the primary goals and illustrate how this program could act in a multi-faceted way to promote healthcare recruitment and retention. Through continual program improvement and widening recognition, the HCTRS will continue to grow into the future, while working to improve rural healthcare workforce recruitment and retention in rural BC.

Acknowledgements

The success of this program has been possible due to the generous support and collaboration of many parties, including the rural communities and schools, the health authorities, and the post-secondary institutions across the province. Thanks to Laura Widmer for creating the map in Figure 1.