Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a common cardiovascular disease, associated with a high rate of morbidity, mortality, and hospital readmission1. There have been several advances in the management of CHF, however, the long-term all-cause mortality rate has improved little over time, and the rate of readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge remain high2. Increasing age, living alone, leading a sedentary lifestyle, and the presence of multiple comorbid conditions are associated with early readmission2. The current management of CHF requires a multidisciplinary approach, and involves four domains of care, associated with biomedical care, psychosocial care, self-care or self-management, and palliative care3.

Self-management of CHF refers to where the individual is responsible for actively managing day-to-day activities, such as compliance and administration of medications, weight monitoring and lifestyle modifications4, and is an important component of CHF management3,4. Multiple factors may influence or impact a person’s ability to self-manage CHF; these include the socioeconomic status of the patient, level of health literacy5, access to ongoing family support6, hospital to home transition7, educational intervention8, and model of care in a given healthcare system9.

There have been limited randomized trials to investigate the efficacy of nurse-led education on the self-management skills and outcomes in rural Chinese patients with CHF. Optimal self-management is believed to improve medication compliance, a key contributing factor for readmission10. However, there is little evidence that self-management is associated with improved end-point outcomes, such as readmission or mortality11.

This study aimed to determine the effect of a structured nurse-led education program on patient self-management, symptom control, and hospital readmission.

Methods

Study participants

The diagnosis of CHF was based on presenting symptoms, such as exertional shortness of breath or pedal edema, and echocardiography studies1. Participant inclusion included those aged 18 years or older, with presenting symptoms classified as II or above as per the New York Heart Association classes of heart failure1, with left ventricular ejection fraction of 45% or less at initial admission diagnosis of CHF. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following: acute coronary syndrome; acute renal failure; ongoing thromboembolic events, such as pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis; acute or chronic respiratory disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); significant vision or hearing impairment; untreated mental health disorder, such as severe depression or anxiety; inability to given informed consent; inability to participate in regular follow-ups.

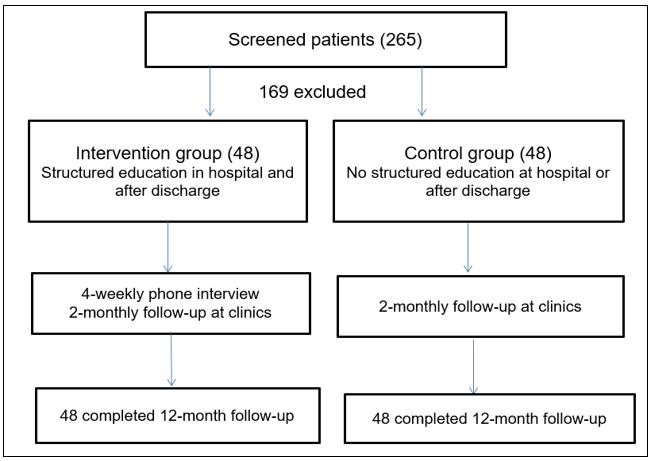

Between January and October 2016, 265 coronary heart disease (CHD) patients were admitted to the Liaocheng People’s Hospital cardiology department and screened for study inclusion, with 96 patients recruited into the study and 169 excluded from the study (Fig1). The research participants were from inland farming communities in the rural Shandong Province of China. Furthermore, the participants did not have access to any other cardiac management or preventative service, which is consistent with other international rural populations, such as Australia12. As per the exclusion criteria, patients were excluded due to acute renal failure (n=27; 16.0%), COPD (n=36; 21.3%), major depression (n=11; 6.5%), and inability to participate in regular follow-up (n=95; 56.2%).

Patients were randomized into the invention or control group using a computerized program. The investigators involved in the outcome assessment of the trial were unaware of the patients’ groupings, with these investigators not being a part of patient care. All patients who were approached for inclusion agreed to participate in the study.

Figure 1: Flow chart of patient selection.

Figure 1: Flow chart of patient selection.

Control and intervention

During hospitalization, the participants were managed clinically according to national and international guidelines3, including pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacological measures, such as water and salt restriction.

The control group received no structured education at hospital or after discharge, but did receive two clinic follow-ups per month, as per standard hospital practice. All control group participants received standard education on self-management during admission, completed in group sessions, with an information pamphlet given upon discharge. General advice on management and the monitoring of clinical factors/features, including fluid and salt restrictions, monitoring of blood pressure, pulse rate, body weight and urinary output, was given by nurses and doctors as per departmental management protocols before discharge.

A structured educational intervention was implemented in the intervention group, in addition to the conventional clinical management of CHF. Nursing staff who completed nationally accredited training in heart failure management provided a 1 hour education session to each of the participants, after their heart failure symptoms were stabilized at the hospital. A second education session of 1 hour was provided before discharge to address any concerns or questions from the participants in relation to the self-care management measures, with families encouraged to attend to discuss patient support requirements.

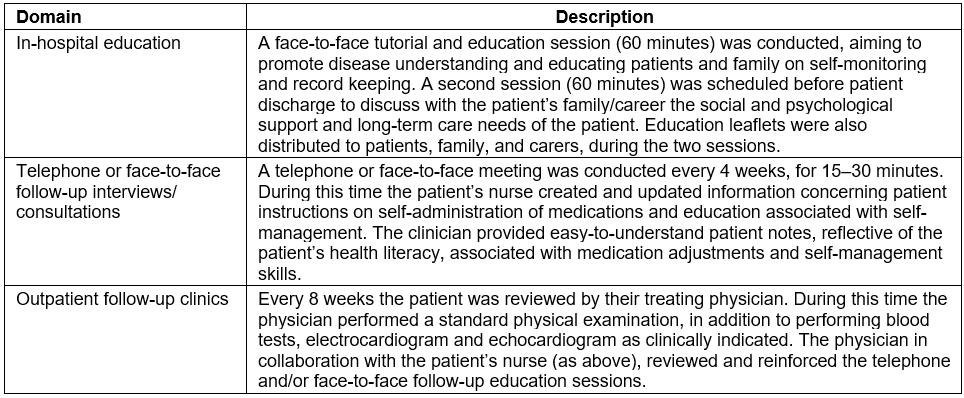

There were six intervention areas, associated with education, self-management skills, positive feedback and interviews, social support, exercises, and rehabilitation. The intervention program was developed according to the self-management theory by Norris et al13. Table 1 provides details on the intervention.

As per the patients’ educational level and knowledge on health care (ie health literacy), a combination of face-to-face teaching and tutorials, printed materials and pictures was provided to the participants and their relatives. These education sessions covered the pathogenesis, risk factors, and short- and long-term management goals for CHF. Comprehensive education on the recognition of worsening CHF symptoms or side effects of medications was also provided. Strategies on lifestyle modification, compliance to medication and follow-ups were discussed, and any barriers to these strategies were addressed.

Patients and their primary carers were taught the skills of measuring blood pressure, peripheral pulses, daily weighing, daily fluid intake and urinary output calculations. Printed charts were provided free of charge to record all measures during the study.

The nurse investigators reassessed participants’ knowledge and understanding of CHF and its management, and their self-management skills, during scheduled follow-ups. Areas of strength were identified and encouraged or praised, and areas of weakness were addressed during the interviews. Patients were encouraged to keep a journal of questions to bring to subsequent sessions. Patients were encouraged to enlist their relatives and families to provide social and psychological support for their illness. The investigators initially engaged participants’ primary caregivers during hospitalization, to discuss the availability of and barriers to social and psychological support, particularly any financial constraints. Community support groups, ranging from volunteer to local government funded groups, were contacted for patients who lived in isolation or were unable to access family-based support. Counselling was provided to those identified as having mild symptoms of mental disorders, such as depression or anxiety.

According to physical condition and exercise tolerance, a detailed exercise plan was developed for each study participant. In most cases, the participants were encouraged to start with light exercises, such as walking, jogging, or performing tai chi. Group dancing and rhythmic exercises were also prescribed to those with improved exercise tolerance.

Table 1: Nurse-led self-management intervention plans

Follow-up

Participants from the invention and control groups were encouraged to attend heart failure clinics every 8 weeks after discharge. In addition to this, the patients in the intervention group received a 15–30 minute telephone or face-to-face consultation every 4 weeks, before the routinely scheduled heart failure clinics. In these consultations, a participant’s self-recorded clinical data (including blood pressure, peripheral pulses, daily weighing, daily fluid intake and urinary output calculations) were reviewed and any concerns or issues were addressed with the nursing investigator, in liaison with the participant’s caring physicians.

As mentioned, control group patients did not receive the additional consultations between routinely scheduled hospital visits. However, participants were encouraged to contact the nursing investigators for any concerns, prior to the scheduled 2-monthly follow-ups at the hospital clinics with their physicians.

Outcome assessment

The primary endpoint of the study was all-cause mortality and hospital admission due to cardiac problems, such as shortness of breath, chest pain, arrhythmia, and syncope. Information on hospital readmission was obtained from the patients and confirmed by reviewing the medical charts at the cardiology or emergency department.

The secondary endpoint was self-management ability for heart failure. The self-management ability was assessed by a Chinese version of the questionnaire originally developed by DeVellis and DeVellis14. There are four domains in the assessment scale: medication management, diet control, social adaptation, and symptom management. There are four points in each of four domains: 1 point = never, 2 points = sometimes, 3 points = often and 4 points = always. A higher score in each domain is indicative of a better self-management ability. The scale yields a total score of 0–20.

The self-management scales were completed by patients before hospital discharge and at the end of the 12-month follow-up. Patients’ cognition, comprehension and language skills were assessed before the forms were completed, and assistance from the investigators was provided to those who had difficulties with the self-assessment questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v16.0 (IBM; http://www.spss.com). A Fisher’s exact t-test was used to analyze categorical data, and an independent t-test was used for numerical data. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Liaocheng People’s Hospital ethics committee (approval number LPH201612, on 17 August 2016). Written consent was obtained from all study participants.

Results

General findings

This study found that a structured educational intervention during hospitalization and after discharge was associated with patients being able to better self-manage, including medication compliance and administration, dietary modifications, social and psychological support, and symptomatic control. The intervention was also associated with a reduction in hospital readmission due to cardiac causes within the first 12 months of discharge.

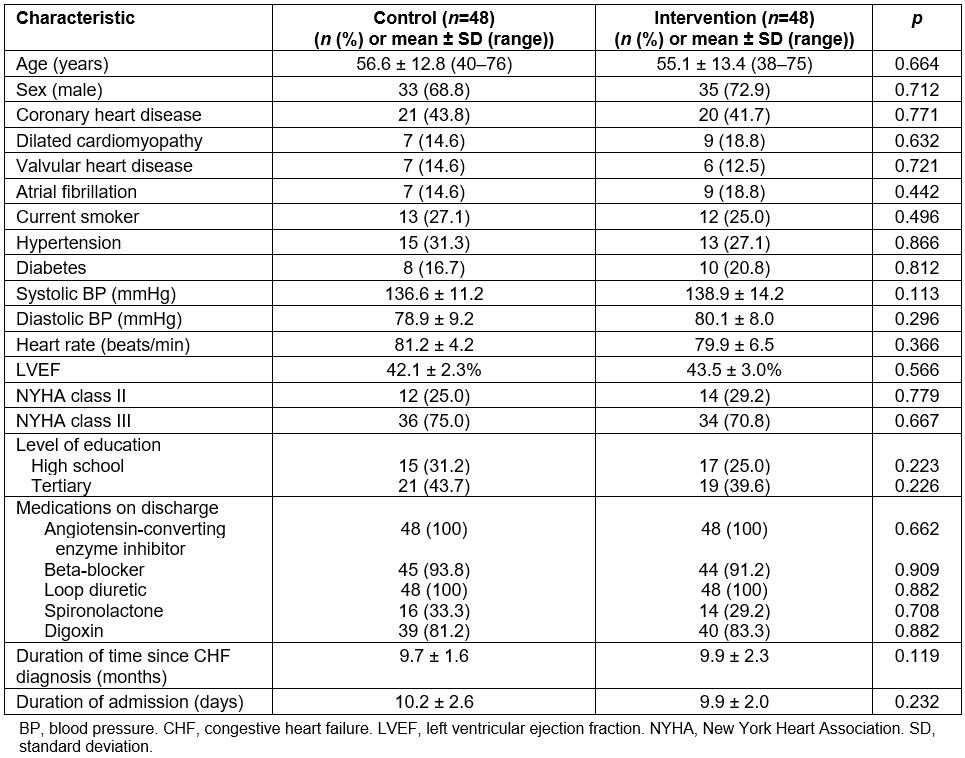

There was no significant (p>0.05) difference in age, sex, baseline cardiac conditions, and left ventricular function between the intervention and control groups on admission (Table 2). More than 70% of the participants were men, and CHD was the primary cause of CHF in approximately 42% of the patients in the intervention and control groups. The use of major cardiovascular drugs was also similar between the two groups at the time of discharge (Table 2). All the control and intervention group participants completed the follow-up studies 12 months after the initial discharge.

Table 2: Baseline characteristics of study and control group participants

Readmissions and mortalities

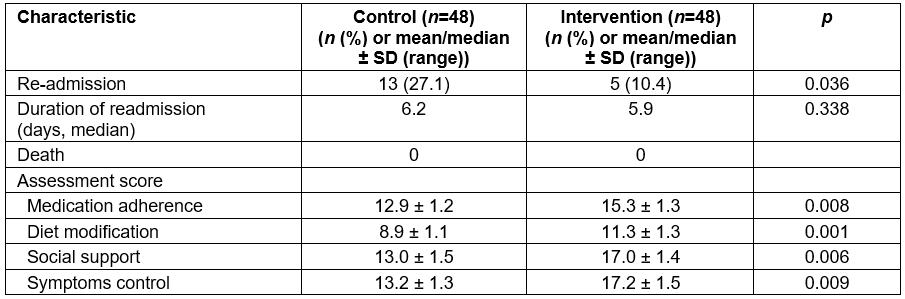

All patients survived to the end of the 12-month follow-up. Five of the intervention group and 13 of the control group participants were admitted during the study period due to deterioration of CHF (p=0.036, Table 3). All were single readmissions. There was no statistically significant difference in the duration of the readmissions (p>0.05).

Table 3: Outcomes of interventions

Self-management assessment

The ability scores on medications, dietary modification, social support, and symptom control of CHF in the intervention group were higher than in the control group (p<0.01, Table 3). As expected, more patients in the intervention group than in the control group reported daily weight measurement at 12 months (91.2% v 6.5%, p<0.01).

Discussion

The management of CHF is complex, often involving a complex medication regime15. Patients with CHF are required to follow diet and exercise recommendations, and to actively engage with clinicians. They are also advised to attend a regular follow-up session to adjust medications according to the progression of symptoms16,17.

There has been a growing body of evidence to support the use of programs to enhance self-management for CHF5-9. Traditional programs, such as hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs, have been found to be effective in improving patient medical outcomes17,18, and are perceived as beneficial by attending patients; however, these programs have inadequate attendance rates16. Furthermore, the majority of CR programs are located in major cities, thus requiring rural and remote patients to travel large distances (>200 km round trip) multiple times per week19. This is not always feasible for chronic disease patients, especially older rural and remote patients. While these programs are effective, the value of the present study and program is that rural patients can access a medically effective management intervention remotely in addition to face-to-face medical support, thus potentially lowering attendance barriers, which are a significant problem in other chronic disease management services in rural and remote areas16.

The present study’s programs involved 8-weekly clinic visits, and monthly telephone and/or face-to-face consultations, which resulted in a higher rate of self-care behavior improvement 12 months after hospital discharge. These results indicate regular consultations either by phone or in person within the first year of discharge improve patient’s adherence to dietary and self-monitoring recommendations. This result is consistent with findings from Anker et al in their meta-analyses, which found that telemedicine in the management of patients with heart failure can reduce morbidity and mortality20. However, two prospective clinical trials not included in their analyses did not support these findings. Therefore Anker et al concluded that the effectiveness of telemedicine in heart failure could not be established20. The present study’s results, while not directly focusing on telemedicine/health, do support the use of telehealth in a rural population. The growing support of telehealth in rural populations is illustrated in Australia by the Royal Flying Doctor Service, who performed 88 541 telehealth consultations in 2016–201721. The authors hope that the present or a similar nurse-led intervention could be implemented in other rural populations and are optimistic that telemedicine, in combination with routine management clinics, is an efficient approach and will become an important feature of management of heart failure.

This study was limited by the small study population in only one region in rural China. Although the patients were representative of the demographics of heart failure patients in this region, the applicability of findings to other patient populations is yet to be evaluated. In addition, cognitive function and other comorbidities, which were not analyzed in this study, may also impact on the outcomes of CHF.

Conclusions

A nurse-led and structured educational intervention during hospitalization and after discharge improves self-management skills in patients with chronic heart failure. This program was associated with improved rural patient medication compliance and administration, adherence to dietary and monitoring recommendations, and social support. More importantly, the readmission rate within the first 12 months of discharge was reduced.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the patients and their families who participated in and supported this study.