Introduction

Although there is a persistent and ongoing deficit in rural health workforce in Australia1-3, recent attention has focused on a strengths based model of developing workforce through educational initiatives4, at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Numerous longitudinal studies show significant short term and long term workforce benefits5-8. However, these positive outcomes have almost exclusively been reported for medicine.

In contrast, educational initiatives to increase the nursing and allied health workforce are not only significantly less studied, but also there are no long term follow-up data of graduates to assess their efficacy. This is curious because these educational solutions to universal rural workforce deficits, including university departments of rural health (UDRHs) for nursing and allied health students and rural clinical schools (RCSs) for medical students began in Australia at similar times9. In fact, rural nursing campuses existed substantially before medical student RCSs, and better short term recruitment of already-rural nurse graduates have been reported10. The importance of coming from a rural background, rural placement during university and positive workplace factors have also been reported for nurses11 However, there are no rural campus or long term outcome data for allied health graduates, a deficit that has been discussed12,13 but studied relatively little14.

One recent workforce study looking at allied health graduates suggested that there may be very high immediate retention following rural training experiences15. After a placement of 2–8 weeks or 1 year through a UDRH initiative, 37.5% of these graduates were found to be practising in RA 2–5 areas in the short term (3 years after graduation). However, these data did not take rural background into account, represented only 10% of the invited cohort, and only nine were practising in rural areas at the time of investigation. Furthermore, ongoing deficits in allied health and nursing professionals in rural and remote locations suggest that this study’s positive result after UDRH placements, which have been in place since 1997, may not be universally the case, and may not be sustained without further attraction and retention strategies.

One early study, which looked at Australian nursing and allied health graduates in the 6 months or more after graduation, also reported considerable early recruitment into rural workforce (25%), but with a great deal of variation between health disciplines16. This early study additionally observed a clear connection with students’ rural background, as well as the benefit they reported from the placement for career development. Having consented to follow-up, the participants in this early study were therefore available to long term follow-up, which the present article represents.

The aim of the present article was to use historic (2000–2003) data to assess factors associated with initial and long term rural practice after UDRH rural placements, to answer the question ‘What factor(s) are significant in the short term (6 months – 1 year), and the long term (15–17 years), with respect to work in a rural location?’ Answers to this long term question are critical in creating an evidence base for long term workforce strategies that will develop effective nursing and allied health workforce interventions.

Methods

Participants

Participants comprised all of those in dietetics, environmental health, health promotion, health information management, health promotion, medical imaging, nursing, occupational therapy, occupational health and safety, pharmacy, physiotherapy, podiatry, social work and speech therapy who were enrolled in an urban campus and completed a rural health placement of at least 2 weeks in their final year from 2000 to 2003. Their placement was funded by the Combined Universities Centre of Rural Health (now called the Western Australian University Department of Rural Health), and has been previously described16.

Intervention and setting

All rural placements were in a town or community greater than 100 km from the Perth central business district, over the period 2000 to 2003. The duration of placement varied between disciplines and students, and ranged from 2 to 18 weeks. Clinical students were placed in rural/regional health services, and non-clinical students were placed in their cognate work environments.

Data collection from undergraduates

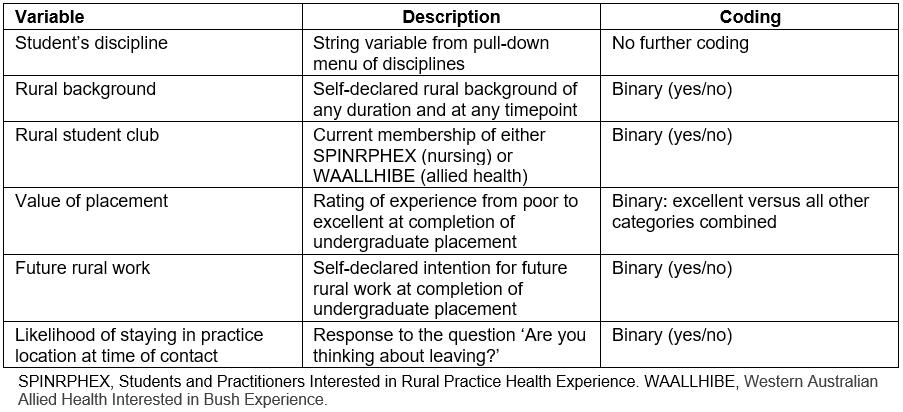

All undergraduates completed an online survey after their rural placement in order to receive their placement funding. The undergraduate survey included questions about the student’s discipline, rural background, membership in a rural student club for their discipline, weeks on placement, the value of the placement for professional development, and whether they were considering future rural work. The variable, description and coding convention of these data are given in Table 1.

Table 1: Definitions for demographic variables collected by survey

Data collection for short term postgraduates

Consenting graduates who had completed an online survey after their rural placement were contacted in the year after their graduation, either by the email or phone information they had provided in their consent document. They were asked whether they were currently working in their discipline of study, their current practice location, rural background and likelihood of staying in their practice location at time of contact. These data included participants from all disciplines who could be contacted.

Data collection for long term postgraduates

Long term follow-up occurred through the online Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA), which not only identifies practitioners by name but also gives their occupation and year of registration, enabling accurate identification. The same database provides the graduates’ primary practice location. However, only registered allied health disciplines are listed in this database, which does not include dietetics, environmental health, health information management, health promotion, occupational health and safety, social work or speech disciplines. The 15–17 year follow-up reported here was therefore limited to nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, pharmacy and podiatry. Due to their very small numbers, the last two disciplines were combined and reported as ‘other’. The time period was defined by the original study, which started in 2002 and concluded in 2004, and corresponds to the postgraduate periods being reported for medical students6.

Classification of practice location

At the time of the original data collection, the most current geographical classification system was the Australian Standard Geographical Classification – Remoteness Area (ASGC-RA)17. To maintain comparability, the same classification was used for the 2018 data. In this system, major cities are classified as RA 1. All other locations from inner regional to very remote locations are classified as RA 2 to RA 5, all of which were considered ‘rural’ for the purposes of this study.

Data management and analysis

Data were entered and maintained in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v24 (IBM; http://www.spss.com). Univariate associations between the independent variables (survey questions) and the outcome variable (postgraduate practice location) were made using the χ2 statistic. These data showed individual relationships between each factor and rural work. Multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression) was used to predict the relative importance of factors identified as being significant, or approximating significance, in univariate analysis. These results showed the factor(s) that remained independently significant after taking all the other factors into account.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (RA/4/20/4686).

Results

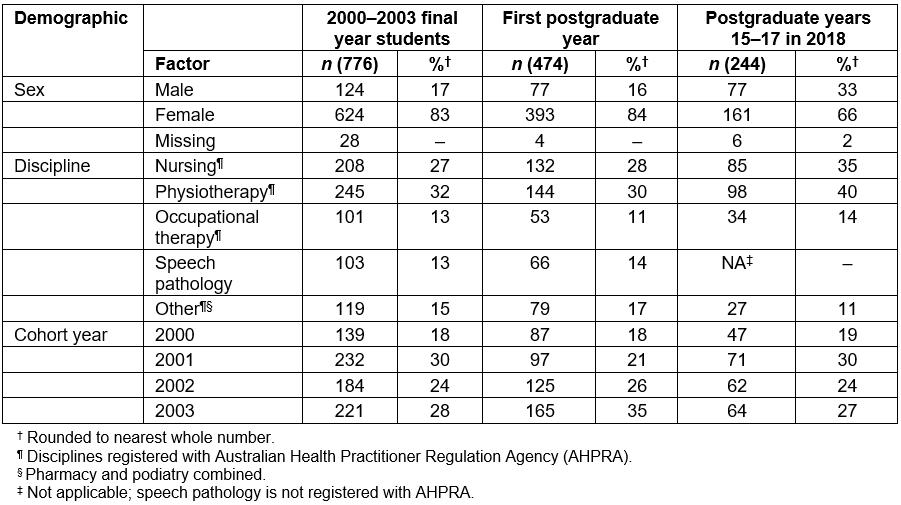

A total of 776 graduates were identified as having at least one rural placement associated with the UDRH, in the final year of their undergraduate degree, from 2000 to 2003. Of these consenting graduates, 474 (61%) were able to be contacted in the year after their graduation, although not all graduates answered all questions, which meant that the number for some variables was less than 474. In 2018, 244 graduates (31%) were identified in AHPRA, 15–17 years after their undergraduate rural placement.

The demographics of these three cohorts are shown in Table 2. Participants in the three contact periods were statistically indistinguishable, except that more males were able to be identified in the final follow-up cohort (χ2=65.59, p<0.000), and that the disciplines differed in the final cohort as speech pathologists could not be identified because they are not AHPRA certified (χ2=68.59, p<0.000).

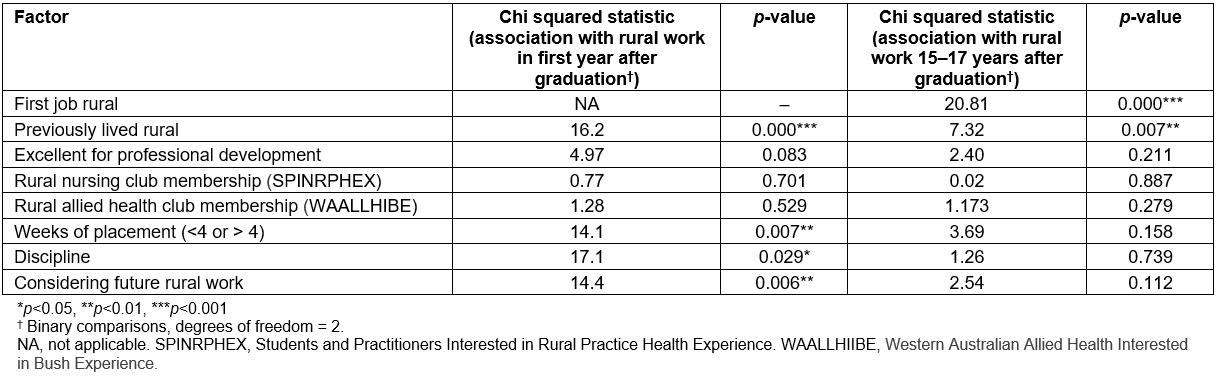

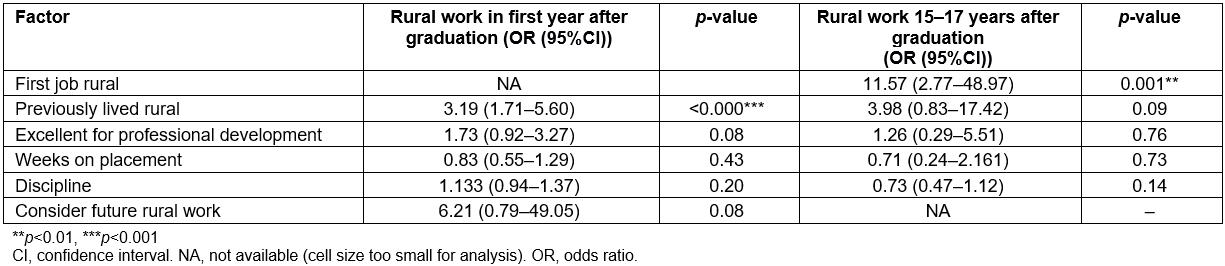

The practice locations of 432 participants were identified the year after they graduated (42 locations were not provided). Of these, 112 (26%) were in rural practice. A number of undergraduate demographic and placement factors were shown to have statistically significant relationships with subsequent rural practice, as shown in Table 3. These factors were then entered into a multivariate logistic regression analysis, which allowed their relative contributions to rural practice to be assessed concurrently (Table 3). This showed that rural background had the strongest relationship with early rural practice. The undergraduate placement being rated as excellent for professional development, and the students’ undergraduate consideration of future rural practice, both approached significance, and so were included for the long term analysis.

Of the graduates identified in AHPRA 15–17 years after their rural placement, most were practising in RA 1 locations (193/240), with the remainder in RA 2 (23/240), RA 3 (19/240) and RA 4–5 (5/240). This gave a total of 47/240 (20%) practising rurally. Although there were fewer females in the final cohort, there was no difference based on gender in urban (RA 1) versus rural (RA 2–5) practice locations (χ2=0.013, p=0.908).

There was a statistically significant association between region practising in the year after graduation, and the region practising 15–17 years after graduation (χ2=20.8, p<0.001), with 13/148 continuing in rural practice, 10 moving from initial urban to later rural practice, and 107 being urban at all timepoints.

Amongst the previously significant bivariate relationships, the two that were found to be significantly associated with long term rural practice were location of first job (p<0.001) and rural background (p<0.007) (Table 3). In logistic regression, considering all factors concurrently, only the region of first job retained significance (Table 4), with rural background approaching significance.

Table 2: Demographics of allied health and nursing cohort at time of placement (2000-2003), in the year after graduation, and in 2018, with each successive cohort compared to the time of placement cohort

Table 3: Univariate associations of surveyed factors with respect to rural work

Table 4: Multivariate associations of surveyed factors with significant univariate relationship to rural work the year after graduation, and rural work in postgraduate years 15–17 in 2018 (binary logistic regression with block entry of variables, p in 0.1, p out 0.2, for concurrent association)

Discussion

This study provides the first long term (15–17 years post-graduation) analysis of practice locations of nursing and a subset of allied health graduates after an undergraduate rural placement experience organised through the UDRH program. The authors show that the single most significant factor predicting long term rural practice was early career rural practice. In logistic regression, this factor was significantly more predictive than rural background, which was the other associate of long term rural practice in univariate analysis.

The finding of early work predicting later work strongly suggests that rural background and rural placement alone are not sufficient to create a rural workforce. These data substantiate the argument made by Durey et al that a rural pipeline approach is needed to reinforce rural practice decisions for all health professionals12. This argument is the same as that which underpins current Commonwealth strategy in funding the Integrated Rural Training Pipeline (IRTP) for Medicine18, which was initiated in 2017 with the intention of providing ongoing training and career opportunities exclusively in the rural context, as is also supported by the advice on a national rural generalist pathway developed by the National Rural Health Commissioner19. The Community Pharmacy Agreement between the Commonwealth of Australia and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia20 likewise supports an ongoing rural pathway for interns and registered pharmacists practising in rural areas. The significant multivariate outcome of the present article – that current rural work relates to early career rural work – suggests that targeted funding schemes for rural work at all levels of the training pathway are needed for the whole health workforce, not just for medicine and pharmacy.

Qualitative work on early career factors associated with attraction to rural practice suggests that mentoring is likely to have retention benefit for nurses21, and that early professional development for allied health graduates in the rural context is likely to prove attractive22. The existence of these qualitative factors suggests rural vacancies alone are insufficient, without additional funding to facilitate targeted recruitment, quarantined precepting, professional development opportunities and other positive factors that the IRTP is making possible for recent medical graduates.

The overall long term retention rate of graduates in this study is consistent with rural practice rates previously identified for allied health practitioners in Australia: 25% of a cross-sectional sample of South Australian allied health workforce were located rurally23. However, the significant addition of the present study is to highlight modifiable factors associated with long term rural practice, so suggesting practical strategies that the Commonwealth might implement to encourage future rural workforce.

Limitations in the study include the initial bias that may have occurred for the first follow-up – for example systematic differences in those lost to follow-up via phone call, such as greater national or international mobility. However, elsewhere an immediate response rate of 61% has been considered an excellent return, and the contact rate of 31% in 15–17 year follow-up of graduates considered to be respectable24. Furthermore, because AHPRA provides an unbiased estimate of workforce location that is not affected by survey response bias, this limitation is relatively unlikely to have affected the long term rural workforce findings, which are based on one-third of the original cohort. Likewise, the relative attrition of women in the final contact should be noted. This is likely due to changes in women’s surname after marriage, attrition from career and/or attrition from clinical work. However, the other demographic characteristics of the three cohorts were similar, and there is no reason in the published literature for considering the rural workforce choices of this male cohort to be unrepresentative. Long term follow-up of rural clinical school medical graduates has not identified a gender difference in rural practice25, as was also the case for this 2018 AHPRA-identified cohort. Finally, the lack of a comparison or control group, who did not undertake a rural placement, limits the generalisability of these findings beyond other comparable UDRH cohorts.

The positive results found in this study are based on relatively small numbers, so there is ongoing need to continue looking at long term relationships after early rural experience. The data reported here are for only one UDRH. A further positive outcome could be obtained by aggregating all UDRH follow-up data into one national dataset. Ensuring a student AHPRA identifier is established, maintained and tracked across student and professional practising life would greatly facilitate this kind of reporting, and could facilitate evidence-based policies.

Conclusion

The authors conclude that there is considerable value in long term follow-up of health graduates, to identify the evidence base on which to fund workforce initiatives. The most significant long term rural practice factor identified in this study was initial rural practice. This suggests that the funding newly provided to the RCSs in Australia to facilitate a rural pathway to not just train but also support careers in rural nursing and allied health is likely to have equally beneficial outcomes if extended to the whole health workforce. This logical sequence is a reasonable extension to the existing UDRH raison d’etre, in aiming for long term solutions to rural health workforce needs.

References

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Factors influencing the geographic distribution of physicians in Iran: a qualitative study