Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as 'an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage'1. Research indicates that poorly managed pain exacerbates disease, increases the risk of complications, increases client distress and anxiety and extends the period of treatment2. Effective pain management is considered essential during end-of-life care and is core work for the discipline of hospice and palliative care.

However, although there is extensive literature on pain relief during end-of-life care for Caucasians, there are few articles that focus specifically on issues associated with pain management for Australian Aboriginal peoples. Indeed, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) identified that the Australian community has failed to study the pain experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples3,4. The scant work that is available highlights the fact that poor pain management remains evident among Aboriginal Australians, and points to the importance of understanding and respecting cultural perspectives on pain and pain management2,5. In order to address this dearth, the present article provides findings from a NHMRC two-year qualitative study on Aboriginal palliative care conducted in the Northern Territory, Australia. The overall aim of the study was to develop a model for Aboriginal palliative care. One component of the study explored and documented issues associated with pain management for rural and remote Aboriginal peoples.

It should be noted that the word 'Aboriginal' is used generically in this article to infer a respect for cultural diversity of Aboriginal Australian culture which consists of a broad range of distinct cultural groups with distinct practices, traditions and laws6.

Methods

A descriptive, phenomenological methodology using open-ended, qualitative interviews with a cross-section of participants (consumers and health professionals) throughout the Northern Territory was used for data collection for the model development. A national panel of experts in Aboriginal health and a Northern Territory Aboriginal reference group peer-reviewed the model.

The findings informing the model development are extensive and rich and hence are being published in a number of articles in order to do the material justice. The findings presented in this article refer to the data on issues of pain management and the fear of euthanasia for Aboriginal peoples.

Research focus

The research questions informing the data collection included:

- What palliative care services are provided and are they meeting the clients' needs?

- How can the services be modified to deliver a culturally appropriate, innovative and exemplary model?

- What strategies are needed to develop and apply the model developed?

In short, the research was concerned with: What is? What works? What is needed? The generic model developed from the findings has been called a 'Living Model'7 to indicated that it incorporates all important factors that can be applied to the unique circumstances of the variety of healthcare services working with Aboriginal peoples during the end-of-life trajectory.

Ethics clearance

This project was conducted in compliance with the NHMRC guidelines on ethical matters in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research8 and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies' guidelines for ethical research in Aboriginal Studies9. Permission and authorisation was obtained from a number of research ethics committees: The Human Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Health and Community Services (formerly Territory Health Services); Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin; the Central Australian Ethical Committee, Alice Springs; the Human Research Ethics Committee of Charles Darwin University (formerly Northern Territory University); and the Central Queensland University. Approval was sought from relevant Community Councils (Chairs/Elders as appropriate) and sought from all individuals prior to participating in the project.

Strict confidentiality was promised to participants in this study and so no identifying information associated with any quote from participants is used in the publications. The rationale for the need for reassurance of strict confidentiality as an imperative for this study is based on two important considerations. First, the sensitive nature of the cultural information provided by participants necessitates strict confidentiality. Second, the small size of the communities from which data was collected can mean that any information about a participant can potentially lead to identification.

It is important to note that all the stories and sources of information are only used in publications with the permission of the person and the community involved.

Participant group

All communications with Aboriginal peoples and communities regarding introduction, progress and review of the project was conduced by an Aboriginal health worker. Progressive consultation secured informed and reciprocal understanding of the research process during data collection, while respecting Aboriginal knowledge systems and recognising the diversity and uniqueness of each community and its individuals.

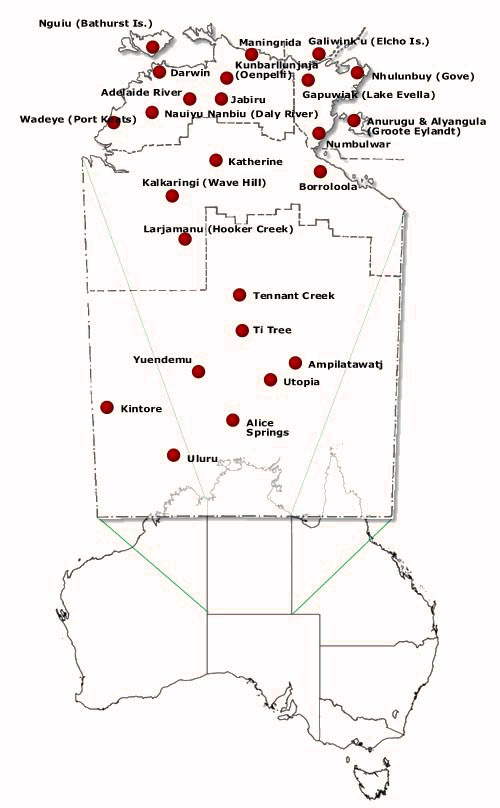

The interviews were conducted in four geographical areas in the Northern Territory: East Arnhem Land (Maningrida, Millingimbi, Elcho Island, Nhulunbuy, Yirrkala [adjacent to Nhulunbuy], Angurugu), Katherine Region (Borroloola, Ngukurr, Katherine), Alice Springs and Darwin (Fig 1). As the following Australian Bureau of Statistics10 figures demonstrate, the populations in these areas are small (Table 1) and, thus, the seventy-two interviews completed for the research represents consultation with a substantial portion of individuals in the area.

Figure 1: Map of the study area in the Northern Territory, Australia

Table 1: Australian Bureau of Statistics population figures for locality of research10

As explained previously, because of the small population base for the areas from which participants were enrolled, full details of participants cannot be given for confidentiality reasons. It will have to suffice to report that there were a total of seventy-two interviews completed with a wide range of participants in the above-named areas, including patients (n = 10), carers (n = 19), Aboriginal health care workers (n = 11), healthcare professionals (n = 30) and interpreters (n = 2). The majority of participants (87.5%) were female. For the purposes of this article, the term 'Aboriginal health care worker' refers to a worker in health care who is Aboriginal.

Data collection

Data collection was through interviews with Aboriginal clients and service providers in the participating communities which, it is important to note, were collected by a respected Aboriginal health worker skilled in palliative care. An interpreter was used if a participant spoke in their local language. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The typed interviews were then entered into the QSR NUD*IST (QSR International, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) computer program and analysed thematically. A phenomenological approach, which aims to describe particular phenomena or the appearance of things as lived experience11, was taken to the recording and analysis of the data. This inductive and descriptive process seeks to record experiences from the viewpoint of the individual who had them without imposing a specific theoretical or conceptual framework on the study prior to collecting data12. All of the participants' comments were coded into free nodes (files or codes in the NUD*IST computer program that are labelled and store similar language texts on one specific topic), which were then organised under thematic headings. An experienced qualitative researcher established the coding and it was then completed by a number of research assistants for the project. There was complete team-member agreement on the coding and emergent themes.

For some of the data collection from remote communities, an interpreter was used for the interviews. For this reason, many of the language texts are not necessarily couched in fluid English. Thus, as a compromise to readability, some of the texts have had words added in parenthesis to improve clarity of meaning. However, even with such changes some of the texts remain somewhat difficult in expression. It was considered important not to change the texts further than this to stay true to the participant and so that the reader still has a sense of the original words spoken by participants.

The following data were collected by an Aboriginal health worker and many of the quotes included are from Aboriginal peoples, including Aboriginal health workers. Because the participants often talk in the third person about Aboriginal peoples (for example, talk about 'their culture', 'the things they do') the verbatim text may at times give the misleading impression that the quotes are from a non-Aboriginal person talking about Aboriginal peoples. The author decided to retain the original expression to avoid changing to the authentic meaning of the statements.

Findings

Pain relief - the most important end-of-life issue

Participants indicated that pain management is the most difficult issue associated with the dying trajectory for Aboriginal peoples.

Most difficult thing about end stage is pain relief.

Cultural issues impact on pain management

Participants indicated that an understanding of an appropriate response to the administration of pain management for Aboriginal peoples can only be understood within the context of Aboriginal culture and family relationships.

But most of the issues we deal with are actually with family members and cultural issues.

In particular, participants reported that, in relation to pain management, there are cultural issues associated with bush medicine, relationship rules, fear of 'payback', difficulties assessing pain, fear of Western medicine and fear of euthanasia.

Cultural Issue - Bush medicine: Participants indicated that the clinical response to pain was most often that of just giving Panadol rather than respecting the importance of 'bush medicine'.

Pain medicine... Panadol. No bush medicine. Just Panadol for pain.

Cultural Issue - Relationship rules: Participants noted that there are strong cultural rules about which family members can engage in the close care that involves pain relief.

... regarding who can actually help us in that family, care for that person... Not appropriate for certain persons to do certain things.

The cultural rules on relationships are very important for pain management during the dying trajectory. Participants indicated that even Aboriginal health workers can be reluctant to administer pain relief to Aboriginal patients in case they are related in some way to the patient.

We find mostly that the health workers are slightly reluctant to do so. One, mostly because they are usually related to the people.

As pain medications can have side-effects such as constipation, the cultural issues with regards to relationship extend to cultural difficulties with toileting.

And their toileting needs... Along with pain relief come constipation... Biggest worry... Also because our family members find it difficult to deal with toilet business from a cultural point of view.

Cultural Issue - Fear of 'pay back': The findings reveal that Aboriginal beliefs about 'blame' and 'pay back' are especially relevant in considering pain management issues during end-of-life care. The explanation of 'pay back' and the need to justify involvement in administering pain medication can be seen in the following text.

[Interviewer summarising: If family did think they gave them too much medicine or made them too sleepy they might get payback?] Yes, all the others would say: well you were looking after that time...

Aboriginal participants of this study indicated that in Aboriginal culture the people in the family network who care for a dying family member are judged on how they care for that person.

Even after death they get blamed for not looking after the old people.

Even Aboriginal workers who are not family members can be reluctant to be involved because of the fear of 'pay back'.

The [Aboriginal] health workers don't because they might get blamed. [Aboriginal] health workers in last 12 hours or couple of days don't do anything the nurses do it because of that blaming thing - makes it very hard.

Fear of 'pay back' can lead to Aboriginal patients enduring unnecessary and severe pain.

... medication I've come across a couple of times where the family don't want to actually give the medication for whatever reason... We don't want people to be in pain but you don't want people to feel that... frightened of payback... But you try telling an Aboriginal person that, no, that woman goes through unbearable pain sometime.

Cultural issues - Difficulties assessing pain: Health worker participants indicated that the starting point for assessing pain is to accept the patients' description of the level of pain experienced.

I said... please investigate because one thing God has not given us the gift to do is feel the pain of others we have to take their word for it.

However, it was noted that Aboriginal peoples are less likely to report their pain, and the reasons given are that they have a higher threshold of pain and complain less.

... Aboriginal people I've found since I've been here have very high threshold for pain and so it is very difficult. They won't tell you a lot of times when they are in pain. And so it is very difficult to assess them. They don't complain very much. They definitely seem to have a higher threshold for pain and take a lot more than what you would expect them to take.

Also, assessing levels of pain can be difficult for cultural reasons, for example, men who are playing leadership roles within the community may not express their pain for fear of appearing 'weak'.

We find a lot of the men too are very, very stoic and it is very, very hard to assess their levels of pain because their role in the community is to be the strong person of the family, but when they are dying they don't like to be seen as weak and sick so that makes it quite tricky trying to assess the pain they are going through...

Cultural issues - Fear of Western medicine: Complicating issues further are the Aboriginal peoples' concerns about being involved with Western medicine. Participants indicated that the side-effects of drugs are not necessarily understood and concern is expressed about the number of medicines used and the effect of those medicines.

Sometimes big scared to give the tablets to the patient. Sometimes trust Balanda medicine... Sometime not, because do not know what that medicine doing.

The sleepiness associated with pain medication is recorded as an important concern.

Yeah, [makes the person sleepy?] Drugs, too many heavy drugs. ... some medications seem to stop the pain but sometimes makes them really sleepy and tired and the family don't understand that. Yeah, they [the family] get frightened.

Fear of addiction is another concern associated with pain relief for Aboriginal peoples.

Where pain management is administered by medical staff who do not provide sufficient information to the Aboriginal person and their family, Aboriginal peoples will make assumptions that the Western medicine is the cause of the patient's condition worsening.

If we doesn't get the feedback then we just think about that doctor that did that something wrong - he has given something else to make him really sick.

The findings also reveal that Aboriginal peoples are nervous about injections as a mode of pain relief administration. Even the technical equipment associated with clinical care becomes a metaphor for death.

Troubles out here with syringe drivers, syringe drivers in this community at the moment are associated with death.

Health worker participants indicated that where possible they use orally administered tablets or skin patches to avoid this fear.

However, the findings show that the fear of western medicine is reduced where the Aboriginal person has clinical experience as a health worker.

Cultural issue - Fear of euthanasia: The findings reveal that the Aboriginal fear of Western pain management is informed by assumptions regarding the possibility that the pain relief drugs will 'kill' the patient.

People get very scared about putting medicine in a drip like morphine in drip for pain, family can be worried that your medicine is actually killing them rather than helping them feel comfortable. That big thing.

Participants expressed concerns that pain medication speeds up the dying process.

Because at that end stage they feel frightened that they will kill them [Too quick?] Yes, too quick and some of them just don't want that responsibility.

Participants expressed 'horror' about the Western notion of euthanasia.

... when we had the euthanasia focus. I was at [name location] at the time and a lot of Elders come down and just want to sit and talk about it and say their feelings and see what our feelings are... because they had real horror at the belief that we would just euthanasia people because we didn't want them to suffer.

A most important issue in regard to concerns about euthanasia for Aboriginal peoples is the cultural practice of passing on traditional knowledge as an integral part of the end-of-life experience. Pain medications are seen by participants as potentially interfering with this process.

But I guess in Aboriginal culture the passing on of knowledge at that stage in life is a key component to the cultural survival. So there was a key concern that people would be leaving without passing on the knowledge.

Effective strategies

Health workers aware of Aboriginal peoples' difficulties with pain management reported a number of strategies found to be effective such as developing trust, involvement of doctors for administration of pain medication, providing support, giving information to reduce fear to the 'right' person in the family network and building up service provision.

Effective strategy - Developing trust: Developing relationships of trust is seen by participants in this study as an important aspect of negotiating the problems associated with pain management and 'pay back'.

Full on blaming... Senior people here there is more trust; it is not as easy to blame one of us because that trust is there...

Effective strategies - Timely involvement of clinic staff or doctors for administering pain medication: An important part of developing trusting relationship is to know when to involve other people who are considered more appropriate to administer pain medication. Participants indicated that the clinic staff can be involved without fear of 'blame' or 'payback'.

If there is a problem between the family, I don't want to get blamed so [name] takes over and do it for me. Other communities I don't know because the trust relationship might not be there between clinic and certain families and also within families themselves. Too frightened to give medication... deliberately ask clinic staff to do that.

Because of issues of 'blame' and 'pay back', health worker participants indicated that they do not want to create a negative relationship with Aboriginal peoples by being involved in end-of-life care where they can be seen as responsible for the patient's death.

Because the way it is perceived in palliative care and end stage that the last medication that is given to the patients before they die is the one that puts them over the edge... Health workers reluctant to take on that responsibility... Especially if there is blame coming from the family.

If available, this is an important role for doctors who are considered the appropriate people to do this work. It is considered important that doctors, not health workers, are involved in the administration of pain relief.

Health workers generally don't like the responsibility... but the doctors are willing to come and do home visits with us.

Effective strategy - support: With ongoing support, the indications are that Aboriginal families can deal with pain management issues.

If they were concerned [about pain management] they could phone us and we would go out and help them out at that time. But the ones that I've dealt with have been pretty good with it... Odd one that is really quite good... pass comfortably with no pain I rather see someone slowly drift off into sleep.

Health workers provided vignettes to affirm their satisfactory experiences with pain management and Aboriginal families, as can be seen by the following example.

A little boy 3 months ago, a special story, he had been in community 24 hours I was on call. He was really comfortable and I said to father you call me if you need to. His father was giving top-up doses of sub-cut morphine, they knew all about it and they were managing it superbly.

Effective strategy - Information to reduce fear: The need for health professionals to engage in effective communication with Aboriginal peoples on the use and effect of drugs is seen by participants of this study as essential for pain management.

Frightened... Medication new to them. (Might cause them finish up early.) Scary thing... Need to be careful with family... Need to talk to the doctor more. Need more information about medicines... frightened will be blamed for giving too much... blamed for last stage of medicine.

Aboriginal participants who are familiar with Western pain relief, and thus less frightened of it, indicated that explanations from medical staff about pain management assist with reducing the fear associated with such interventions.

You know because they will explain to us. Once we get that feedback from the doctors it is very good, yes.

Effective strategy - Giving right information to right person: As described in findings elsewhere13, it is important to give 'the right story to the right person', as demonstrated by the following statement, which refers to giving instructions of who in the community to talk to about pain relief.

We explain exactly what it is for, give them options - what pain relief they have. If do go to [name location] liaise heavily with [name] so she take over with same story with minimum of confusion. She is up to speed so they do not have to answer all those questions.

Effective strategies - Service provision: Participants spoke about the various services that assist with pain management. However, the services are limited. Outside of business hours, Aboriginal peoples have to rely on the ambulance service. For that reason it was suggested that palliative care education should be targeted at ambulance personnel.

Ambulance service very helpful for after hours. After hours have to go to hospital... not too much choice about that.

The community clinic nursing staff are the significant providers of pain management.

The clinic used to go and do it... give them.

Where there is a reliable family member who is prepared to be involved, the clinic staff will involve them in the care.

... or if there is a responsible person in the family they'd [clinic staff] give that person -

Discussion

As Figure 2 outlines, the findings from the study highlight the difficulties associated with pain management in relation to end-of-life care for Aboriginal peoples. To understand the problems of pain management it is important to appreciate many of the cultural practices and beliefs of Aboriginal peoples. As Fried14,15 argues, when caring for Aboriginal peoples it is important to recognise and defer to the cultural knowledge and personal authority of family members and relevant others within the Aboriginal community.

Figure 2: Overview of findings.

The findings indicate the importance of those involved in pain management being aware of the complexity of cultural relationship rules that determine who should and who should not be directly involved in providing physical care. These findings are not only relevant insofar as the provision of medication is concerned, but are also relevant in dealing with toileting issues that arise as a consequence of the side-effects of some drugs. Problems with toileting issues associated with pain relief for Aboriginal peoples are noted elsewhere with specific mention of the undesirable effects of the use of MS Contin® without adequate bowel care16. The side-effects of opioids, including constipation, appear to be as common in Aboriginal peoples as they are in Caucasians17.

The findings indicate that cultural concerns about 'blame' and 'pay back' are key factors impacting on pain management. Involvement in pain relief can be accompanied by fear of 'pay back', because family members can worry about being seen as causing the death or not looking after the elderly person properly. As outlined in full in the publication of further findings from the study18, for Aboriginal peoples blame is apportioned when death occurs19,20. Individuals identified as bearing some of the blame can then proceed to engage in a process of conflict resolution after a death21.

Indications are that Aboriginal peoples can endure severe pain as an alternative to accepting pain relief as a result of their fear of pain medication. Developing relationships built on trust between health professionals and Aboriginal peoples is reported as the most important strategy for overcoming such fear. Also, it is important to know and respect the fact that to avoid concerns of 'blame' only certain people should administer medications - the local doctor or clinic nurse is usually the most appropriate person to do so, with those related to the family in any way to avoid doing so.

The findings also reveal the many difficulties associated with assessing pain in Aboriginal patients. It was noted that Aboriginal peoples may have a higher threshold of pain and they are less likely to complain of experiencing pain. Additionally, there are cultural issues that must be borne in mind, for example, men do not want to appear weak by expressing their pain. Honeyman and Jacobs5 document the fact that, because of cultural beliefs, Aboriginal peoples do not commonly complain about their pain. Similarly, Fenwick2 explains that Aboriginal peoples do not complain about pain because they are by nature a tolerant people, a characteristic that translates into stoicism when experiencing pain. In a later paper, Fenwick and Stevens3 explain that, for Aboriginal peoples, pain is understood in relation to the external world and can be caused by such things as breaking of tradition or violation of taboos, crossing into forbidden land or speaking to the wrong relative at the wrong time. For this reason, a culturally specific stigma is attached to the causes of pain, possibly making the sufferer too ashamed to complain. In addition, their findings indicate that Aboriginal peoples may view the nurse as a 'white fella healer' with the ability to 'see within', as with traditional healers. The Aboriginal patient thus assumes the nurse knows their pain level and there is no need to talk about it. Indeed, if the Aboriginal patient discusses pain it could bring 'shame' because it would be disrespectful to those who 'know'.

Complicating the issue of pain management is the fear of Western medicine. This fear stems from a number of key factors. First, Aboriginal peoples may not understand clinical notions of pain relief. Second, they may fear the sleepiness that is a side-effect of certain drugs. Third, Aboriginal peoples may be concerned about addiction to medications. Fourth, Aboriginal peoples may make assumptions that the use of pain relief drugs may worsen the physical condition of the patient. Fifth, Aboriginal peoples can be fearful of technical equipment, such as needles and syringe drivers, that can become a metaphor for death.

Blackwell17 agrees that it is realistic to expect that Aboriginal peoples will be very frightened of white medicine, because it is only used when someone is very sick, and they will have almost certainly have tried traditional methods first. She also points to the fact that the syringe-driver is an unwanted impractical encumbrance which is viewed with considerable fear and suspicion and recommends the use of transdermal delivery systems such as fentanyl patches instead.

One of the most significant fears recorded in the findings is that Western pain medications will be used for euthanasia by speeding up the dying process. Sullivan et al.16 similarly provide vignettes indicating there is a widespread fear on the part of Aboriginal peoples that Western drugs such as morphine are administered during end-of-life to hasten death. For Aboriginal peoples, this issue has serious cultural implications because the end-of-life is a significant time for passing on traditional knowledge and secrets. When the patient is an Elder or community leader, their condition has particular implications for the community because the passing on of the cultural knowledge they hold is of the utmost significance6. As Blackwell17 points out, it may be necessary for the dying person to pass on stories and knowledge about their land and its sacred sites to the next keeper of the land.

The findings detail a number of strategies that can assist with pain management. The use of 'bush medicine' is important but there are some indications that at present these practices are ignored. A most important strategy is the building of a trusting relationship through the provision of information. As detailed elsewhere13, the communication of information must involve giving 'the right story to the right person'. Vignettes from the present research demonstrate that where there is a relationship of trust and knowledge, local Aboriginal peoples can also be successfully involved in the pain relief.

Conclusion

The insights provided by a diversity of Aboriginal peoples and the health professionals who care for them, provide valuable wisdom as to how best ensure effective pain management is made available to Australia's first peoples. At the core of this information is the need for cultural sensitivity and respect.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank NHMRC for providing the funding. The author would also like to thank others involved in conducting the study, including Jennifer Watson, Beverley Derschow, Simon Murphy, Rob Rayner, Hamish Holewa, Katherine Ogilvie and Mary Anne Patton.

References

1. Foley K. Pain assessment and cancer pain syndromes. In: D Doyle, G Hanks, N MacDonald (Eds). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998; 310-331.

2. Fenwick C. Resource tackles Aboriginal pain issues. Australian Nursing Journal 2001; 8: 37.

3. Fenwick C, Stevens J. Post-operative pain experiences of Central Australian Aboriginal women. What do we understand? Australian Journal of Rural Health 2004; 12: 22-27.

4. National Health and Medical Research Council. Acute pain management: scientific evidence. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 1999.

5. Honeyman P, Jacobs E. Effects of culture on back pain in Australian aboriginals, Spine 1996; 21: 841-843.

6. National Palliative Care Program. Providing culturally appropriate palliative care to Aboriginal Australians: resource kit. Albury, VIC: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Mungabareena Aboriginal Corporation, Wodonga Institute of TAFE and Mercy Health Service, 2004.

7. McGrath P, Watson J, Derschow B, Murphy S, Rayner R. Aboriginal Palliative care Service Delivery - A Living Model. Darwin: UniPrint, Charles Darwin University, 2004.

8. National Health and Medical Research Council. Values & ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Online (2004). Available: www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publications/pdf/e52.pdf (Accessed 7 July 2006).

9. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research (AIATSIHR) Ethical Guidelines for Research. Online (2004). Available: http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/research_program/publications (Accessed 5 July 2006).

10. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population and housing, urban centres and locations 2001. Cat no.2016.7, 2004. Canberra: ABS, 2004.

11. Streubert K, Carpenter D. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1995.

12. Polit D, Hungler B. Nursing research: principles and methods, 5th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1995.

13. McGrath P, Ogilvie K, Rayner R, Holewa H, Patton M. The 'right story' to the 'right person': Communication issues in end-of-life care for Aboriginal people. Australian Health Review 2005; 29: 306-316.

14. Fried O. Many ways of caring: reaching out to Aboriginal palliative care clients in Central Australia, Progress in Palliative Care 1999; 7: 116-119.

15. Fried O. Providing palliative care for Aboriginal patients. Australian Family Physician 2000; 29: 1035-1038.

16. Sullivan K, Johnston L, Colyer C, Beale J, Willis J, Harrison J et al. National Aboriginal Palliative Care Needs Study, Final Report. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2003.

17. Blackwell N. Cultural issues in Aboriginal Australian peoples. In: D Doyle, G Hanks, N MacDonald (Eds). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998; 799-801.

18. McGrath P, Holewa H, Ogilvie K, Rayner R, Patton M. Insights on the Aboriginal peoples' view of cancer in Australia. Contemporary Nurse 2006; (in press).

19. McGrath C. Issues influencing the provision of palliative care services to remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. Australian Journal Rural Health 2000; 8: 47-51.

20. Weeramanthri T, Plummer C. Land, body, spirit: Talking about adult mortality in an Aboriginal community. Australian Journal of Public Health 1994; 18: 197-200.

21. Eckermann A, Dowd T, Martin M, Nixon L, Gray R, Chong E. Binan Goonj. Bridging cultures in Aboriginal health. Armidale, NSW: University of New England Press, 1992.