Introduction

Despite many suggestions for how to sustain rural access to health services, recruiting and retaining rural healthcare professionals (HCPs) continues to be a significant challenge1,2. In Canada, the proportion of outflow of regulated nurses, or those leaving the profession, is higher in rural and remote areas compared to urban areas (7.4 v 5.9%)3. The barriers to recruiting and retaining HCPs in rural areas are well documented: limited resources, few professional development opportunities, and complex interpersonal and professional ties to the area4. Rural and remote area nurses have high turnover rates, report high levels of psychological distress and emotional exhaustion and experience frustration with a lack of staff and exhaustion with orienting new staff5. One useful strategy to support new staff, reduce turnover, and enhance HCP retention in these areas is formal mentorship programs4.

Mentorship is defined as a relationship between a more experienced mentor and a less experienced mentee6, the goal of which is to help the mentee develop professionally, integrate into the workplace, promote employee engagement, improve job satisfaction, increase networking, and allow for succession planning for both individuals6,7. The positive outcomes of the mentoring relationship experienced by the mentor, mentee, and workplace (improved sense of belonging, career optimism, competence, professional growth, security, and leadership readiness8) may positively offset a number of challenges reported in rural areas. A positive workplace culture and supportive working environment support rural nursing recruitment and retention2,9. A mentor’s professionalism and attitude can also assist a mentee’s adaptation to the workplace and enhance commitment and loyalty to the organization6,9.

Formal mentorship can be described as a relationship set up through an organization in which the mentor and mentee are matched, as opposed to a more informal mentorship in which the relationship develops over time with the mentor and mentee self-selecting each other10. A successful mentoring relationship has a number of essential elements: a clear agreed set of objectives and goals, formalized communication and training, matching of mentors and mentees, and evaluation and review of the program post-completion6,11,12.

Despite considerable research on the benefits of mentoring, the impact of mentorship programs for rural HCPs has received little attention. To this end, a rural-specific mentorship program was implemented and evaluated to assess the program’s influence on supporting rural mentorships, easing workplace transition, strengthening community connections, and encouraging recruitment and retention in rural communities.

Methods

Setting and sample

This pilot study took place in a western Canadian province with a total population of 1 million people. Registered nurses (RNs), nurse practitioners, and physicians that worked in a community with a population of less than 10 000 people were invited to participate. Individuals could participate as mentees if they had been in their position for less than 18 months and mentors had to be employed within their position for 18 months or more.

Recruitment information

Recruitment materials were distributed via managers, clinical nurse educators, and mentorship representatives within rural health authorities and facilities, mailed to physician and nurse practitioner clinics, and distributed via the provincial nurses’ association email list on the researchers’ behalf. Interested participants were asked to contact the principal investigator and were provided with a link to a confidential online registration.

Fifteen mentees and 43 mentors volunteered to participate and completed the online registration (Table 1). All 15 mentees were RNs and were matched by the principal investigator with an RN mentor from the pool of mentors based on mutually self-identified priorities for matching and similarity of responses. Mentors and mentees were not necessarily from the same rural community; in all but one pair, the mentors and mentees did not know each other.

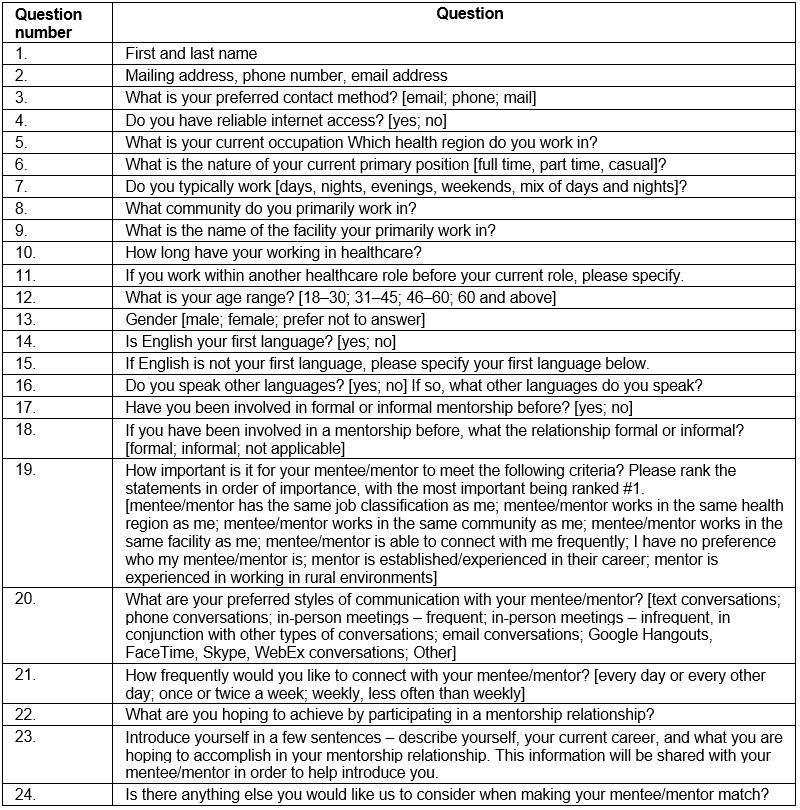

Table 1: Mentorship program registration questions

Mentorship program development and operationalization

The province of Saskatchewan is divided into specific health regions and only the larger health regions offer mentorship programs for employees, which were varied and offered inconsistently. The programs featured mentor and mentee participants who worked within the same facility. The largest health region offered a face-to-face, in-person mentorship program orientation session for new employees, including those who were non-HCPs. This orientation was hosted in the largest centre in the province and incurred costs for the health authority in terms of travel, time off, and hotel stays for participants. Notably, organizations within rural areas were often not sending employees to these sessions due to issues such as limited replacement staffing, limited numbers of new hires, limited mentors, and unpredictable weather.

To accommodate HCPs who worked in rural areas, adaptations to the original program were required to make the mentorship program accessible, sustainable, and cost effective. A 4-month mentorship program was adapted from the health authority with their permission and in collaboration with a health authority representative who had experience offering a mentorship program to a variety of employees in urban settings. An adapted mentorship program orientation session was offered via videoconference technology to accommodate participants from rural areas, who could connect from either home or work. The approximately 60-minute orientation sessions were provided to each mentor–mentee dyad by the principal investigator and a research assistant, who acted as the mentorship coordinators for the project.

Establishing the relationship and program orientation

Program materials were provided in advance of the orientation session and included a mentorship handbook and PowerPoint slides. The session started with an overview of the program and its goals, introductions, and the mentor and mentee’s rationale for participating. Material presented included reviewing what mentorship is, a discussion of what is unique to working in rural areas, benefits of mentorship, phases of mentorship, roles of mentors, connecting to the community, effective behaviors of mentors and mentees, giving and receiving feedback, expectations, goal setting, frequency of communication and connecting with each other, and role of the coordinators as facilitators. In most cases, the mentors would establish the next steps for connection between the pair. The 15 workshop orientations took place over a 3-month period at times that were mutually convenient for the dyads.

The mentorship coordinators maintained regular contact with the dyads throughout the 4-month study period via email. Emails were sent every 2–3 weeks to provide support, guidance, and direction. The email communication served as encouragement to the dyad to check in with each other as all but one of the dyads did not work in the same community or facility. Each email aimed to move the mentorship relationship forward by providing suggestions for dialogue between the dyad.

Evaluation of and experience with the rural mentorship program

Following the completion of the 4-month mentorship program, participants were asked to participate in a voluntary follow-up telephone interview. They were also asked to complete an evaluation survey 3 months after the program ended, to allow time for reflection.

Data collection and analysis

Fourteen participants (eight mentors and six mentees; 47% of participants) volunteered for the follow-up telephone interviews. Digitally recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Interview questions included an assessment of the program’s ability to support rural mentorships, ease workplace transition, strengthen community connections, and encourage rural recruitment and retention of healthcare providers. Following transcript cleaning, interviews were coded and analyzed using thematic analysis13. The principal investigator and research assistant reviewed the transcribed interviews; coded the data broadly to generate initial codes; collated the codes to generate potential themes; reviewed and refined the themes; and further defined, described, and analyzed the themes.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board (BEH 15-244), and organizational approvals from four involved health regions within the province were obtained prior to study commencement.

Results

Demographics

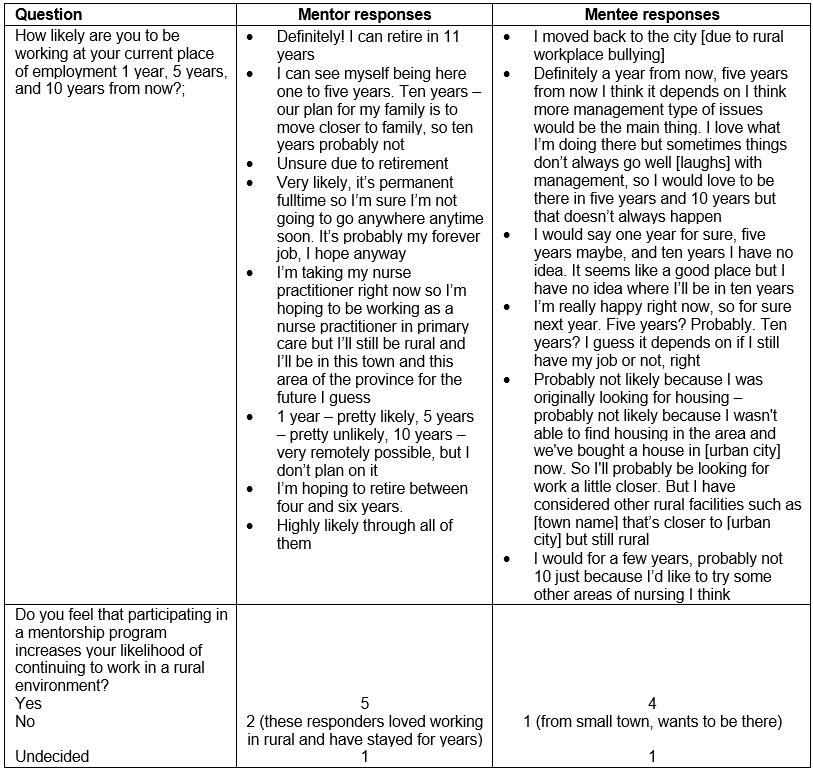

Fifteen RN mentor–mentee dyads were recruited to participate in the pilot rural mentorship program (Tables 2,3). Mentor and mentee preference in terms of priority factors when being paired, and the preferred style and frequency of communication, were variable and individualized. Mentees identified their goals for the relationship as obtaining support, advice, and guidance as they began their careers as RNs in a rural workplace. Mentors’ goals included sharing knowledge, providing a trusting relationship for a new nurse, helping the mentee thrive in a rural environment, and building community connections. Both mentors and mentees were asked two questions during the interviews that assessed the likelihood that they would remain in the rural community: ‘How likely are you to be working at your current place of employment 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years from now?’ and ‘ Do you feel that participating in a mentorship program increases your likelihood of continuing to work in a rural environment?’ Participant responses are shown in Table 4.

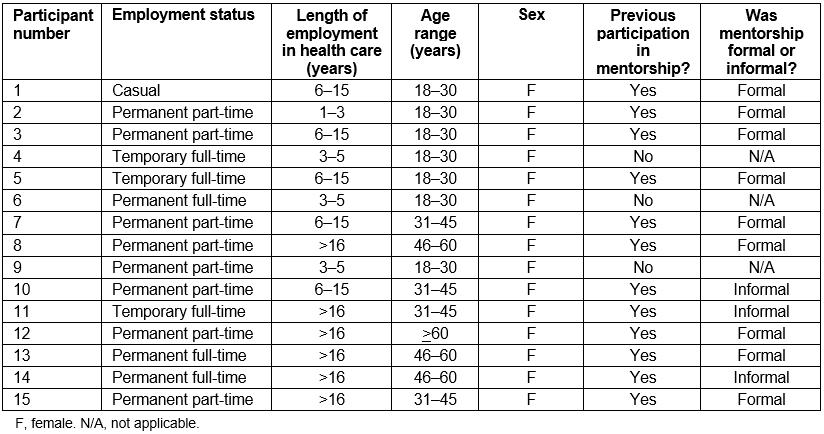

Table 2: Mentor demographic information

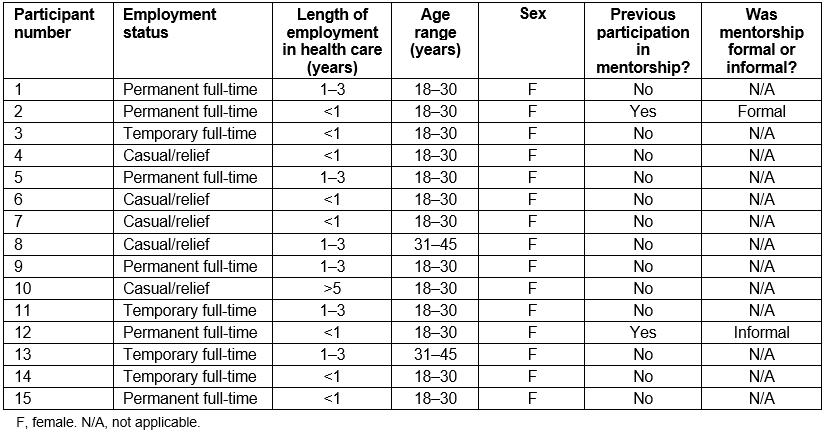

Table 3: Mentee demographic information

Table 4: Mentorship program participant retention and intent to stay

Mentorship program evaluation survey results

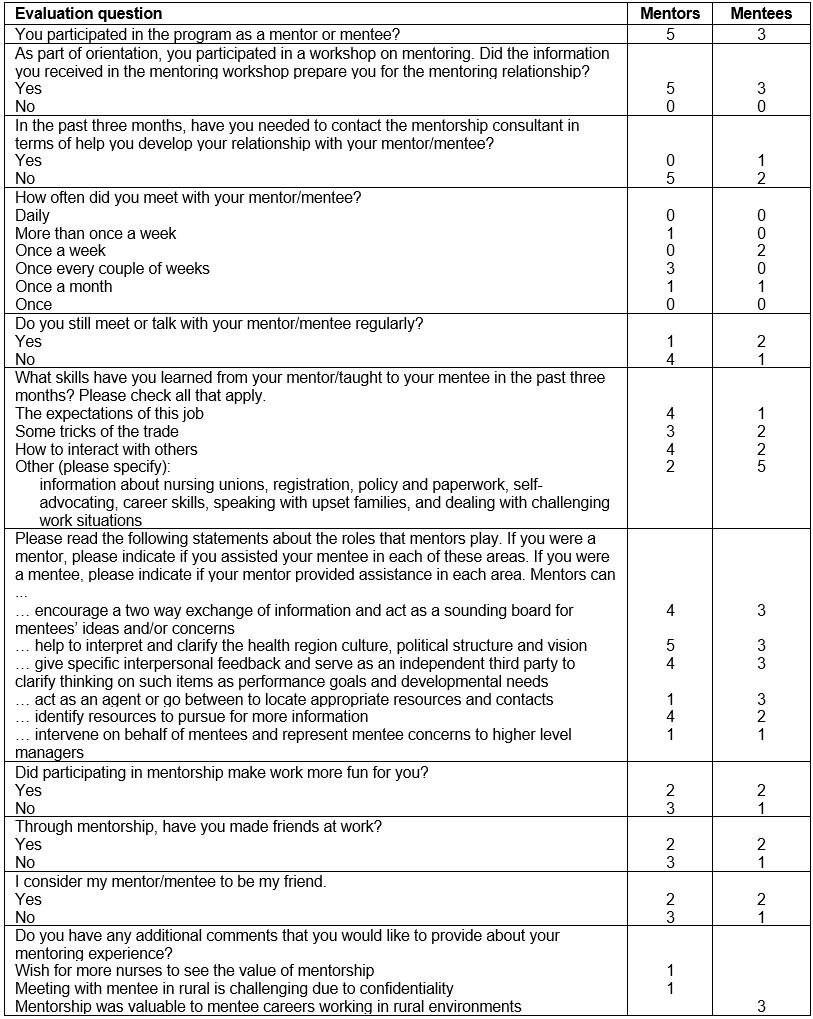

All participants were sent a mentorship program evaluation survey post-completion. Five mentors and three mentees completed the survey and not all participants responded to every question (Table 5). All respondents believed the orientation session was beneficial in preparing them for mentorship. Overall, respondents mutually benefited from the relationship.

Table 5: Mentorship program evaluation questions and responses

Interview themes

Three themes were identified from the 14 participant interviews as key considerations when implementing a rural mentorship program: connection, communication, and support.

Connection: Connection is a broad theme that describes a variety of relationships that participants formed throughout the mentorship program. These include connections to their mentor/mentee, themselves, their work, their colleagues, and the larger community. Numerous factors contributed to the formation, or lack, of said connections. Facilitators included individual willingness to explore connections, mutual understanding of goals, emails with conversation topics from mentorship coordinators, and living in the same community as their mentor/mentee. Barriers included lack of time at and outside of work hours and not being able to connect in person with their mentor/mentee. Connections made during this time were consistently beneficial in the eyes of the participants; whether personal, professional, or social, the connections were meaningful and highly valued by both mentors and mentees.

Nurses described the community as a key factor in welcoming them and fostering connectedness. Community in this context was the individuals residing within the rural location and the social events in which they engaged. Introduction to these community connections was gained primarily through co-workers or other mutual connections. Participants’ acceptance within the larger rural community was reported to be essential in promoting meaningful connection and decreasing feelings of isolation:

When you come into a small community you have to feel like you belong and the community makes or breaks that situation. (Mentor 5)

Participants reflected on the consequences of feeling disconnected in a rural environment and how this has the potential to significantly and negatively impact their personal and professional wellbeing:

I’ve talked to people who came out to rural and they hated it, because they didn’t have anybody, any support, or any friends … it’s nice to have somebody outside of work to talk to who understands. (Mentee 15)

For other participants, new connections to the larger community were viewed as the foundation for enhancing professionalism by creating healthy boundaries between professional and personal relationships:

We are all connected to various community members in different ways, it’s hard to know how to stop the blurring of personal and professional lines. Mentorship may help to build more professionalism, which I think would be healthy in my rural community. (Mentor 4)

Lastly, interpersonal connection aided in normalizing feelings and was essential for promoting staff retention and workplace transition for new nurses:

When I was first starting, I just felt so lost and ill-equipped. Having someone to normalize [those feelings] gave me hope for the future – that it would get better … and helped me to stick it out. (Mentee 2)

Mentees who felt connected to other nurses were more inclined to push through the difficulties of role transition, thus remaining in their rural nursing position and enhancing staff retention.

Communication: Communication encompasses the logistics of corresponding between mentee–mentor dyads during the program, participants’ communication with program coordinators, and future communication about and promotion of rural mentorship programs. Methods and frequency of communication varied from text to phone call to email to in-person conversations, ranging from every day to once a shift to every few weeks. These communications were sometimes just to ask a quick question about a clinical situation and at other times were longer, to discuss a range of personal and work-related topics. The longer conversations often involved the topics suggested by the coordinators.

Both virtual and in-person communications were used throughout the rural mentorship program. Many participants desired more face-to-face communication with their mentor or mentee and often felt isolated and that distance was a barrier to quality communication and decreased the frequency thereof:

Distance!! Not physically connecting with the mentee was difficult. (Mentor 13)

However, the informal, self-directed nature of the communication made the commitment to the program manageable; as one mentee mentioned:

It didn’t seem like just another thing on our plate. (Mentee 4)

In a setting where nurses already have numerous responsibilities, some participants felt flexibility was an absolute must for a rural mentorship program.

Some participants expressed interest in more frequent scheduled communication, with program coordinators acting as a third party to guide conversation in a productive direction:

We intentionally kept things pretty unstructured, I might have been better with a little more structure to keep me accountable. (Mentor 4)

Participants found the bi- or tri-weekly email check-ins helpful for guiding discussions and generating ideas for conversation, but felt a handful of more formal check-ins with the coordinators could have improved the continuity of communication.

Participants expressed the need for future communication about mentorship programs, including promotion of rural mentorship programs via effective marketing:

I really think if you sold your facility as using mentorship and you have good mentors, and you can show success stories, I think that would go a long way in actually because you’re promoting mentorship, but at the same time you’re actually recruiting employees. (Mentor 8)

Participants felt staff would be more inclined to participate in and support mentorship if it was openly talked about and integrated into the culture within their facilities. Furthermore, managers were viewed as being key players in terms of the transparency of mentorship amongst staff as well as integrating mentorship programs.

I think it would be really beneficial for managers to talk about [mentorship] during the hiring process. (Mentee 2)

Support: Support was described as interpersonal and professional assistance provided to the mentee from the mentor as well as to the mentor from the mentorship program and management. The support mentees felt from mentors was overwhelmingly positive while support for mentors and mentorship programs, primarily from management, was lacking.

The emotional support mentees gained from their mentors helped ease their transition into nursing practice in a rural facility. Mentees frequently expressed feeling grateful and appreciative for the support provided by their mentor. Challenging clinical situations, managing relationships with colleagues, and tips for work–life balance were some areas for which mentees frequently sought out and received support:

I was just very grateful to have her to talk to, especially when I was alone as a charge nurse without a manager or anything … I did feel like it really got me through my toughest times. (Mentee 2)

Mentors felt they would benefit from increased support in the form of formal mentorship training. They were keen to gain specific skills, knowledge, or tips about mentoring to empower them and instill confidence in their ability to mentor:

Maybe a little bit more guidance for me as a mentor being that I’ve never done it before … even like a book or course or something. (Mentor 5)

Participants wanted to increase their knowledge base via improved access to online mentorship resources such as books, videos, or articles; essentially, they wanted the mentorship coordinators to suggest reliable sources of information on effective mentorship skills and techniques. Enhancing self-efficacy through these means may go a long way towards encouraging experienced staff to get involved in mentorship. It’s convincing mentors that they have something to give … some of them feel like they don’t have anything to offer, and I really challenge that … anyone can be a mentor. (Mentor 8)

Support from the organizations and unit or facility managers was identified as crucial to integrate mentorship into their facilities:

Make it known throughout facilities, encourage it in our workplaces, make it a normal and talked about aspect of nursing! I think it would encourage better culture in our rural facilities. (Mentor 4)

Furthermore, managers were viewed as being in a position to promote mentorship when recruiting new staff:

When they are hiring new staff I think they need to do it as an incentive, especially to recruit to rural areas. I know that definitely was an incentive for me when I first graduated because I was moving five hours away from my family, to a town where I knew not a single soul. (Mentor 1)

Participants thought support from managers would encourage a shift in organizational culture towards promoting and supporting cohesive staff involvement in mentorship, welcoming and encouraging questions, and viewing mentorship as mutually beneficial.

Discussion

The results of this project highlight the pivotal roles that mentors, mentees, and the healthcare organization have in developing, facilitating, and sustaining mentorships in rural areas. Zey’s mutual benefits model proposes a triad relationship between these three partners when considering mentorship within organizations14. The authors of the present study propose that an additional partner be integrated when considering rural mentorships: the rural community. Each member has an opportunity to gain something positive from the mentorship experience: the mentee benefits from increased interpersonal and professional support, guidance, and direction provided by their mentors that make them feel comfortable, confident, and welcomed into their new rural roles; mentors feel proud of their contribution while gaining a trusted colleague; and organizations benefit from increased staff productivity, teamwork, and ultimately reduced employee turnover14. The rural community also benefits because committed and connected HCPs are more likely to remain in their positions, improving continuity of care for rural residents5.

Strengthening connections within the tetrad is fundamental to enhancing the quality of rural mentorships. Enhancing facilitators and mitigating barriers to connection formation requires attention and effort from all individuals involved. The interpersonal relationship between the mentor and mentee is vital to establishing and sustaining the mentorship over time6. An open and trusting relationship allows the mentee to feel comfortable asking questions, sharing concerns, and seeking advice15; the mentor benefits from this connection by sharing knowledge and expertise and giving back to the profession16.

Regular communication between the dyad is critical to foster and develop a successful mentorship12 based on encouragement, constructive comments, openness, mutual trust, respect, and a willingness to learn and share17. Most study participants preferred face to face communication but this was not always possible; technology (eg videochat) can be employed to bridge that distance. For mentee–mentor pairs who do not live in the same community, their connection could be further strengthened by discussing common interests beyond rural nursing and getting involved in a similar activity (eg yoga) in their respective communities.

Managers and senior administration can look at creative opportunities in an effort to support mentorships. For example, managers can take on the role as mentorship coordinator as they frequently know their staff the best, allow staff time off to attend mentorship orientation sessions, allow mentees to work supernumerary at first to adjust to their new work environment, discuss mentorship with all new employees to show support for mentorship early, or perhaps make mentorship mandatory for all new employees. Organizational leaders are key players in advocating for policy changes to include mentorship as they provide the program infrastructure, facilitate program promotion and awareness, recognize and value those involved, and role-model mentorship behavior7. Finally, nurses who feel a sense of connection to rural communities are more inclined to remain in their positions, continuing to provide excellent service to its residents; this is in direct contrast to rural nurses experiencing isolation and feelings of disconnectedness, who are more likely to return to urban areas18. Rural healthcare facilities do not exist as silos independent from the rest of the community, but function integrally within it. It is difficult to depart from a workplace when employees feel invested in the community and its members on a deeper level.

Marketing is important for creating awareness about the availability of mentorship programs and recruiting participants. Participants felt program promotion needed to occur from all levels within the organization and that support from managers and upper-level management was lacking. The program implemented here was an external program, organized outside of specific facilities, and therefore managers may not have been aware of its existence. Increased communication between the program coordinators and individual facilities where mentors and mentees were located would have addressed this oversight. Greater involvement from managers and senior leadership result in a greater likelihood of mentorship being integrated into the unit or facility culture and becoming adopted19. Information sessions about mentorship in general can raise awareness and promote mentorships, especially when hiring new staff. Better communication by program coordinators and managers is also required to promote the roles and expectations of mentors. Potential mentors may need to be shoulder-tapped by managers or colleagues to recognize the contributions they can make towards the personal and professional development of a new employee.

Participants identified the lack of formal mentor training as a program limitation. Adequate preparation of mentors is critical for success in such a collaborative relationship. A workshop (in person or online) could occur prior to commencing the mentorship program to give mentors foundational knowledge of how to be an effective mentor, clarifying their role and thus empowering them throughout the mentorship process. Beyond the online database of mentorship resources (eg peer-reviewed articles, videos, books, podcasts) suggested by participants, a blog or other form of online chat site may prove effective in connecting rural nurses involved in mentorship to those participating in mentorship in other geographic locations. The intention would be to provide mutual support to one another and reduce feelings of isolation throughout the mentorship process. Furthermore, mentor training may aid in improving nurses’ personal perceptions of the value of their rural nursing experience.

Support from the rural community towards mentorship can include connecting new staff with other community members to highlight community activities and resources and simply make new staff aware of what their community has to offer. This could be communicated through other nurses or staff of the healthcare facility, managers, newspaper advertisements, announcements on staff bulletins, a community events website, or a Facebook page. Community ambassadors can be identified to meet with new staff and familiarize them with the rural community and its resources in order to promote integration and connection to the rural community. Community involvement increases feelings of acceptance, cooperation, unity, and support, all of which aid in retention of new rural nurses20.

Limitations and future research

This study involves only one province in Canada and therefore the study findings have limited generalizability. However, key elements of the mentorship program and development can carry over to other rural areas internationally. This study aimed to recruit RNs, nurse practitioners, and physicians, but only RN mentees volunteered to participate; thus, the results may not be applicable to other HCPs. Suggested future research includes trialing mentorship programs for other HCPs who work in rural areas and conducting the study on a national or international scale. The use of online mechanisms for connecting mentors and mentees introduces a great potential for mentorship programs to be offered to healthcare employees working in rural and remote areas nationwide and internationally. Future research could also be directed towards examining formal mentor preparation in rural healthcare environments. A longitudinal study investigating whether participating in a formal rural mentorship program actually increases retention in the rural area is another suggestion for future research.

Conclusion

Mentorship has positive effects on recruitment and retention of HCPs. Participants in this study believed that mentorship was beneficial. However, greater strides need to be made to facilitate mentorships in rural areas. The responsibility not only resides with the mentor and mentee, but also with health organizations and rural communities. Members from all groups need to be committed and contribute to mentorship for rural mentorship programs to be successful and sustainable. Rural residents are often underserved due to insufficient numbers of HCPs working in rural areas, along with a limited number of services offered. The greater the numbers of HCPs that can be recruited and retained to work within rural communities, the greater the likelihood the community residents will have timely and appropriate access to quality health services. These services can result in positive patient outcomes and greater community health.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for funding from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation and the assistance of Saskatchewan Health Authority representatives, Cody Howell, Emily Wright, and Leona Anderson, who helped facilitate this research project and share health authority mentorship resources. The authors also thank Drs Donna Rennie, Sonia Udod, June Anonson, and Olufemi Olatunbosun for their mentorship and guidance in project planning, development, and critical review of the study proposal.

References

You might also be interested in:

2013 - Strategies for moving towards equity in recruitment of rural and Aboriginal research participants