Introduction

Allied health services address the disabling consequences of disease and injury. In Australia, the number of allied health professionals per head of population decreases by remoteness, and consequently the numbers are disproportionately low compared to need in rural and remote areas1. A primary function of the National Rural Health Commissioner position is to improve allied health services in rural and remote Australia2.

The provision of quality rural placement experiences for allied health students has been a significant strategy to address these health workforce shortages3,4. Where medical5,6 and allied health7 students are exposed to positive rural experiences, they are more likely to consider rural practice in the future.

Rural placement programs provide important opportunities for students to learn a diverse range of skills7, which enable them to be ‘work-ready’ effective rural clinicians. Such programs include rural service learning placements, which provide allied health services where previously there have been none or few8. Service learning is a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection9, increasing expansion of placement capacity and enhancing accessibility to health care through student service provision for populations with high unmet health needs10. These service learning placements appear to strengthen students’ work-ready attributes of problem solving, adaptability, self-confidence, autonomy and interprofessional practice11.

Work readiness has been defined as the extent to which graduates are perceived to possess the attitudes and attributes needed for success in the work environment12. Work-ready attributes and skills include a positive attitude, ability to communicate effectively, ability to work in a team, mutual respect and trust, self-management and reflection, willingness to learn, decision-making skills and the ability to adapt and be resilient13,14.

The University Centre for Rural Health (UCRH) is one of 17 University Departments of Rural Health across Australia funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health to deliver quality rural health training and therefore encourage growth in Australia’s future rural health workforce. The UCRH is in the Northern Rivers region of the north coast of New South Wales (NSW). The region has a growing elderly population, a higher percentage than state average of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, areas of high unemployment and socioeconomic disadvantage, and a high burden of chronic disease15,16.

The UCRH’s work-ready placement program aims to offer allied health students unique, positive rural learning experiences that will encourage and equip them to practice rurally.

Origins and context of community-based work-ready placements

In 2016, the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training agreement between the Commonwealth Department of Health and the UCRH stipulated a substantial increase in the number of allied health student placements in the Northern Rivers region. This necessitated a twofold increase in placement weeks. An innovative approach to identifying potential placement sites to include more than the traditional hospital/clinic based sites was required. The design of the program was based on service learning models in other University Departments of Rural Health8-10,17.

Guided by the North Coast Primary Health Network’s regional analyses of health needs18, small rural towns within the UCRH footprint with limited or no available allied health services were identified. The program established placements in residential aged care facilities, pre-schools and primary schools in towns of both disadvantage and high health need, with the intention of providing services across the town (eg placing students in all of the pre-schools and the primary schools in that town). Identifying gaps in service was important to ensure that allied health students would be adding value in in areas of need, rather than competing with or undermining services of existing allied health professionals.

UCRH’s work-ready placement program

Funded by the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training agreement, the UCRH program began in 2016 with occupational therapy and physiotherapy students. It has since expanded to include speech pathology. The program consists of a community-based work-ready placement where students are placed in pairs for 4–10 full-time weeks in either a school or a residential aged care facility. The UCRH employs allied health clinical supervisors to provide student support, visit students at placement sites to give direction and education, conduct assessments and give students instruction and feedback. Unlike most traditional student clinical placements, these clinical supervisors are not continuously located on site although they are available to students by email or phone. Students may also experience group supervision, tele-supervision and interdisciplinary supervision. The supervisory model is designed to facilitate students’ autonomy, model effective clinician behaviours, be tailored to students’ needs, and guide project and resource development. This model is particularly beneficial in giving students confidence in their capabilities, developing students’ work readiness skills and independence, and facilitating innovation in practice.

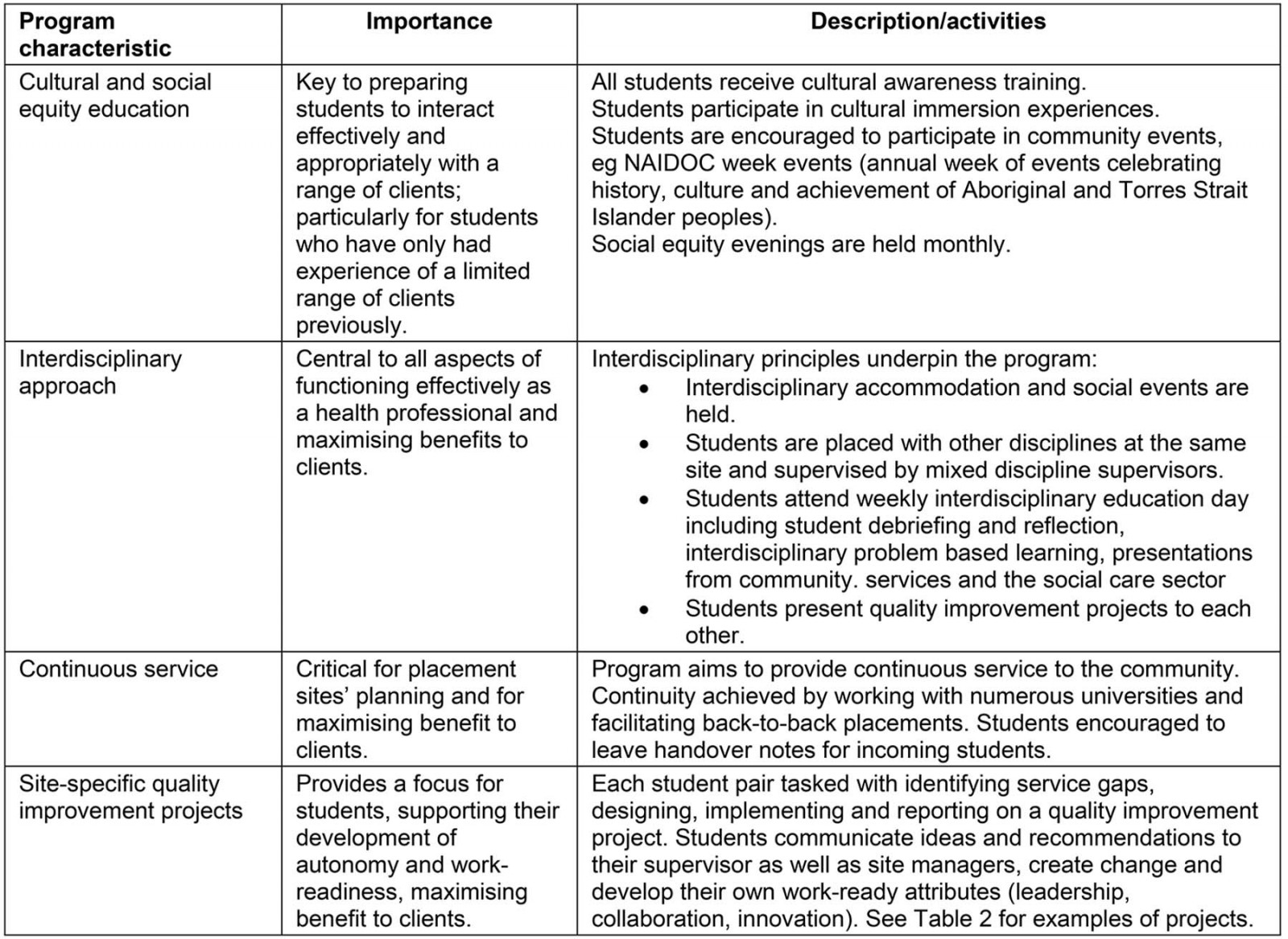

Success in a rural placement requires preparation before the placement with detailed site descriptors, access to affordable accommodation including internet, opportunities for social interaction and community engagement as well as opportunities to interact with supervisors7,19. In addition to these fundamental features, several defining characteristics of the UCRH program are described in Table 1. These include a focus on cultural training, interdisciplinary experience, education and supervision, and continuous service and quality improvement projects on placement.

The aim of this article is to describe the origins, nature, fundamental properties and outcomes of the program and to illustrate the challenges and opportunities it has presented, to inform the development of rural placement programs across Australia. There are few descriptions of such programs for rural Australian allied health students in the published literature (from only three locations)4,8,17,20-22. This article adds detail to this literature including a full description of the program in the Northern Rivers region and its fundamental properties such as a strong interdisciplinary focus, continuous placements outside of the acute care setting, and the cultural and social equity education provided.

Table 1: Defining characteristics of the University Centre for Rural Health’s work-ready placement program, Northern Rivers region, New South Wales

Methods

From February 2018 to December 2018, all occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech pathology students from the University of Sydney who were on the program (the largest group of students on the program) were invited to complete a validated questionnaire23 rating the quality of their placement. Students were recruited by one of the research team approaching them in person in the last week of their placement to describe the study, provide information, answer questions and invite participation (including emphasising that participation was voluntary). Completion of the questionnaire indicated consent to participate. The questionnaire included students’ assessment of aspects of the program that were of greatest interest: students’ perceptions of the overall quality of their placement and of supervision, how well the placement (and supervision on placement) matched their learning needs, the extent to which they had improved their work readiness and ability to work autonomously because of the kind of supervision they experienced on placement, the quality of the learning environment in the workplace, and UCRH staff involvement and support before and during their placement.

Ethics approval

The research was granted ethics approval from the University of Sydney (ref: 2015/466) and was part of a wider evaluation of the UCRH’s education for all students.

Results

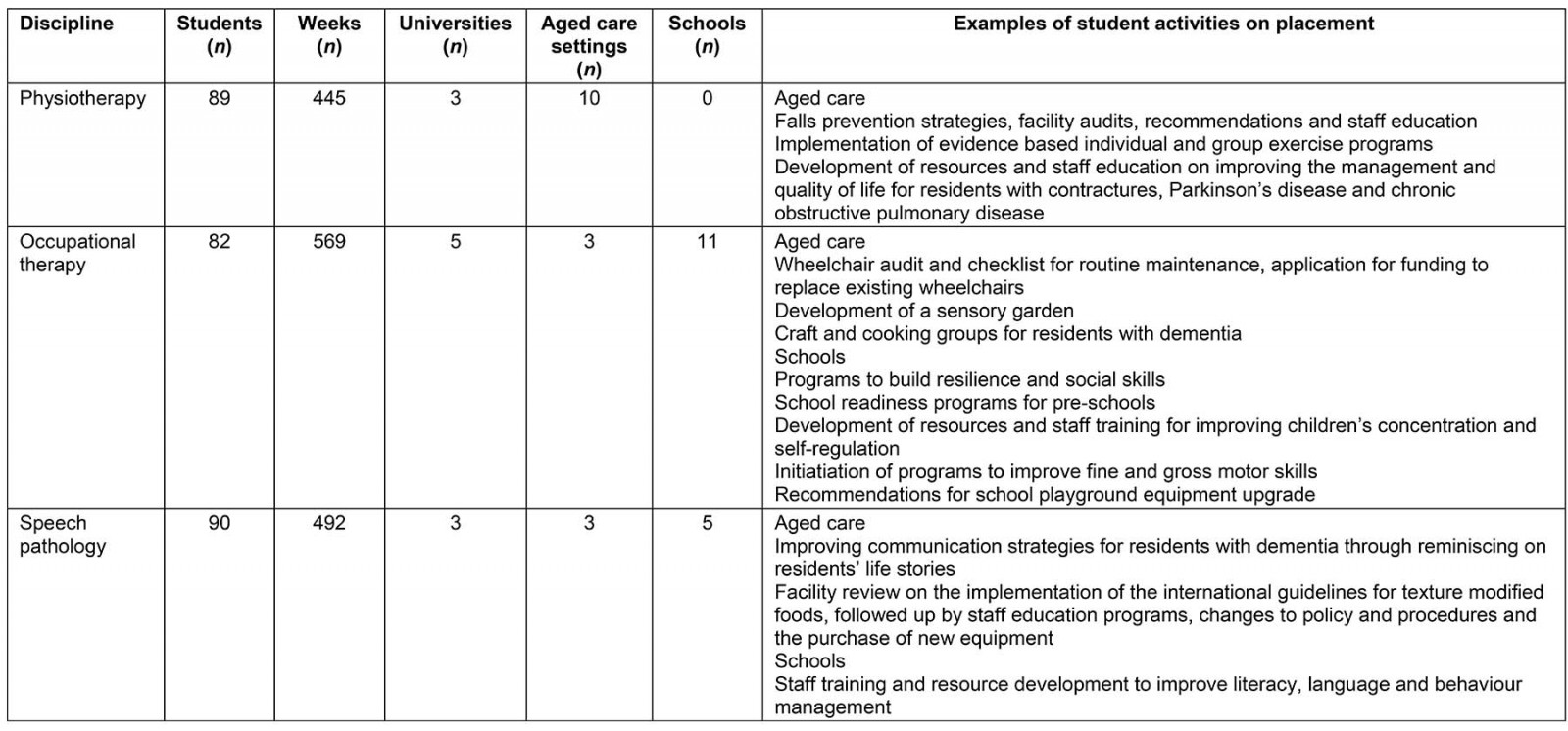

In 2018, the program facilitated placements for 261 allied health students (around one-third of the total number of allied health students on placement with the UCRH) from a range of universities for 1506 placement weeks, in 12 schools and 10 aged care facilities. Most students were in their final undergraduate year or were postgraduates (eg undertaking a postgraduate physiotherapy course following a first degree), although occasionally students in their penultimate year participated in the program. Table 2 describes the capacity of the program and student activity in 2018.

Table 2: Capacity of the University Centre for Rural Health’s work-ready placement program, Northern Rivers region, New South Wales

Positive outcomes for students

Students highly value the program. They report an increased understanding of the application of their own discipline, other allied health disciplines and their role in the healthcare team. Many students experience a feeling of worth and usefulness, of ‘making a difference’, which can also lead to increased confidence, pride and enthusiasm for their chosen career.

In the program, students work autonomously, use clinical reasoning and problem-solving skills. Students must communicate with different groups of people with various cultural backgrounds including elderly residents with dementia, families, care staff and volunteers, children, teachers as well as staff from other healthcare sectors.

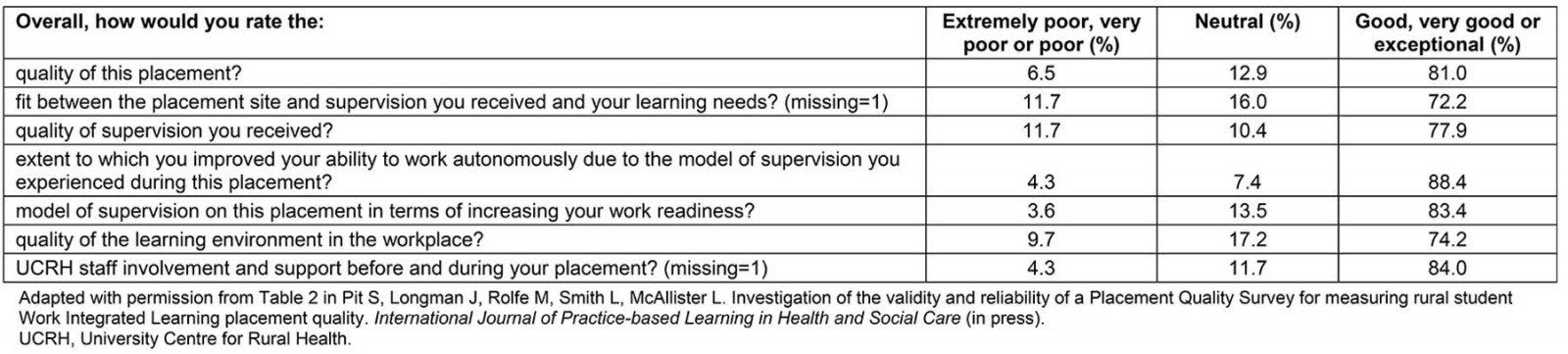

During 2018, 163 of the 185 University of Sydney occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech pathology students who were on the program completed a validated questionnaire (88% response rate). Students were studying physiotherapy (n=83, 51%), occupational therapy (n=32, 20%) or speech pathology (n=48, 29%) and ranged from final year undergraduates to postgraduate students. Students’ ratings of the quality of placement on the program are shown in Table 3.

These results resonate with anecdotal evidence in showing that the majority of students gave a very positive rating to the placement. In particular, 88% rated the extent to which they improved their ability to work autonomously due to the model of supervision they experienced as good, very good or exceptional, and 83% rated the model of supervision as increasing their work readiness as good, very good or exceptional. Additionally, results illustrate that these students valued the support provided by UCRH staff prior to and during placement. The fit between site and supervision and learning needs and the quality of learning environment in the workplace was not so highly rated.

Table 3: Student ratings of quality of program placement (n=163)

Positive outcomes for placement sites and clients

Through engagement with allied health students, schools and aged care facilities reported (in presentations, discussion groups and informal feedback), that they increased their understanding of the roles of these disciplines and the positive impacts they can have on client quality of life. As a result, a number of facilities are now exploring how to source funding so that they can employ allied health clinicians. Having students based in schools and aged care increased the quantity of interventions and care provided to residents and children. Staff from several schools in the program have reported that now it is difficult to imagine teaching some of the children until they have received some occupational therapy intervention around their behaviour. Similarly, aged care staff have reported improved mobility and engagement of residents as a result of student interventions.

Positive outcomes for universities

The number of universities with allied health faculties and the number of students within these faculties is continually increasing, creating intense competition for clinical placement opportunities. The program enabled the placement of larger numbers of students in rural settings (Table 2). It also provided quality, well-received and diverse learning opportunities for students.

Program challenges

The implementation of the program required innovative, interdisciplinary supervision models. Some stakeholders were initially hesitant to be involved in the program. However, after the program had been implemented, enquiries were received from universities, schools and aged care facilities who were keen to be part of the program. Stakeholder engagement and careful attention to aligning universities’ needs, student learning requirements and sites’ needs were important for the success of the UCRH Program.

Whenever possible, the UCRH organised placement blocks back to back by sourcing students from multiple universities. This allowed students to provide a continuous service to the sites. Continuity of service, although a goal, was not always possible. Sites, on average, had students for about 60% of the year. Down time from students enabled clinical supervisors to plan, implement program improvements, develop resources, attend continuing professional education and explore new community placement opportunities.

The roles of the UCRH clinical supervisors were both rewarding and challenging. Each supervisor supported students from several disciplines and universities, varying programs (undergraduate and postgraduate) and across several sites. Supervisors needed to be adaptive to various learning styles of students and provide additional support to students who had limited experiential learning. To address these challenges, the program included allocated time for supervisors to meet regularly to discuss students requiring additional support, plan site visits and for clinical mentoring. The supervisors were also allocated time to shadow other supervisors on placement to learn new skills and supervision techniques.

Ensuring the placement sites were in a confined geographic location meant more time for supervision and less time spent travelling to and from sites. The UCRH purposefully allocated students from different disciplines to the same site. This created an environment for the students as well as the supervisors to learn with and from each other, and provided additional student supervision services and resources for the site.

Students on the program needed to work autonomously, problem-solve, initiate activity and learn in a novel, non-clinical setting such as a pre-school. As some students found this challenging (illustrated by their lower scoring on the ‘the fit between the placement site and supervision you received and your learning needs’ and the ‘quality of the learning environment in the workplace’ items in the questionnaire – Table 3) they needed to be carefully selected by their university. The type of placement and supervision, and the expected learning outcomes, had to be communicated to students prior to commencement to ensure expectations were managed. The UCRH addressed these challenges by communicating expectations regularly with the universities and scheduling opportunities for the students to talk to supervisors about the placement expectations several weeks prior to the placement commencing. These placements were better suited to students in the final years of their degree. Placing the students in pairs also provided added support and helped to prevent loneliness and isolation.

Discussion

University Departments of Rural Health such as the UCRH are well placed to provide interdisciplinary training and rural immersive experiences for allied health students as they facilitate clinical placements for relatively small cohorts of students from multiple disciplines and are therefore able to manage students’ learning and educational activities whilst they are in the region.

The UCRH’s program provides interdisciplinary skill development through interdisciplinary living, socialising, education and supervision. Interdisciplinary skills increase employability and work readiness, particularly in rural settings4,24. Interdisciplinary learning strengthens students’ ability to work in a team, communicate effectively and provide better patient-centred healthcare solutions25.

Positive learning experiences on service learning placements have demonstrated effectiveness in developing skills that increase work readiness and employability8,17,20. The validated questionnaire completed by some students in the program indicated that they perceived the program improved their ability to work autonomously and increased their work readiness. Similar placements have also been shown to improve students’ ability to work in a team, improve self-management, reflection and decision-making skills13,14.

A positive rural placement experience can contribute to changes in students’ perceptions of working in a rural environment and may influence their intentions for the future and/or their future working location22. Student survey data from across the country identified that the factors contributing to this positive experience include adequate preparation and support including accurate information about the placement and the location, subsidised clean comfortable accommodation, a diverse learning environment, positive relationships with supervisors, opportunities for interdisciplinary interaction and collaboration and engagement with the local community22. In the program, students who completed the validated questionnaire indicated that they felt well supported, that the placements provided quality supervision and addressed their learning needs.

The Rural Health Commissioner’s allied health discussion paper stresses the importance of health services, including the right balance of allied health services to optimise the health of rural Australians. The paper acknowledges that currently there is an inadequate supply of allied health services in rural and remote areas to meet demand, and it supports rural placements and service learning models 26.

Anecdotally, the schools and aged care facilities in the program have indicated that they highly value the contribution students make to their clients’ care, and the resources and quality improvement projects that students provide. These findings support other positive outcomes from service learning programs8,17,20.

Further research is required to evaluate all the components of the program and assess their contribution to students’ work readiness and likeliness to practise rurally.

Conclusion

Service learning rural placements are providing allied health services in small rural towns where previously there have been limited or no allied health services. Whilst the program has presented logistical challenges, it offers students a stretching and potentially enriching placement, which students perceive improves their ability to work autonomously and increases their work readiness, and that aims to encourage them to practice rurally in the future.

References

You might also be interested in:

2021 - A case for mandatory ultrasound training for rural general practitioners: a commentary

2015 - Factors influencing the geographic distribution of physicians in Iran: a qualitative study