Introduction

Health worker shortages are a global problem, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where they have a significant impact on the efficiency and sustainability of health systems1. According to WHO, there is a global shortage of 4.3 million health workers, including approximately 2.4 million doctors, nurses and midwives2. By 2030, the global demand for health workers is predicted to reach 80 million, while only 65 million are predicted to be available3. This situation is particularly dramatic for rural and remote areas, which include more than half of the world’s population but only about 23% of all health workers2,4.

Worldwide, countries in sub-Saharan Africa are some of the most affected by health worker shortages5. Estimates suggest that nearly 1 million additional health workers would be needed to bring Africa to the WHO-recommended standard of 2.3 doctors, nurses and midwives per 1000 population6. In Mali, the total number of health workers was 19 368 in 2016, representing a ratio of 5.2 per 10 000 inhabitants, and their retention is low, particularly in rural areas7.

By 2030, it is likely the paradoxical phenomenon of ‘excess’ health workers will occur, due to the overproduction and unemployment of health workers in urban areas, while rural and isolated areas may become ‘health deserts’5. The majority of young health workers prefer to work in higher education institutions or in the private for-profit sector, leading to their unequal distribution between rural and urban areas2.

Several factors explain the shortage and poor retention of health workers, particularly in rural and remote areas. There is an urgent need to better identify and understand these factors, and to propose appropriate strategies to improve attraction and retention. In order to study them, some authors have classified factors of attraction and retention of staff into ‘pull’ (attractive) and ‘push’ (repellent) factors8-10. Pull factors are identified as those that attract a health worker to a new location. They include opportunities to improve employment and/or career prospects, higher wages, better living conditions and a more stimulating environment9. Push factors are those that act to push an individual out of a community. They can include poor working conditions, lack of work opportunities and low wages1,10. A review of the literature shows that, although incentives are important, only selection and training policies should be favoured in order to correct the inequitable distribution of health workers in rural and remote areas11. In Mali, very few studies have examined the various factors that explain the shortage and poor retention of health workers in rural and remote areas. The objective of the present study is to understand these factors with regard to skilled health workers in two health districts of the region of Kayes, Mali.

Conceptual framework

The Lehman, Dieleman and Martineau framework, focusing on low- and middle-income countries, was found to be best suited to this study9. It describes five categories of factors that influence the attraction and retention of health workers in rural areas: individual factors; local environment; work environment; national environment; and international environments.

Methods

This is a qualitative research that took place over a 5-month period (June–October 2017).

Study sites

This study was commissioned by the MEDIK (Maternal Evacuation in Five Districts of Kayes) project and was conducted in two (Yélimané and Bafoulabé) of the five health districts of Kayes, Mali, where project activities were underway. According to the last administrative census of 2009, there were 178 442 inhabitants in Yélimané and 233 926 inhabitants in Bafoulabé. Both districts are rural according to the administrative division of Mali. The region of Kayes has 233 community health centres and 10 referral health centres spread over 10 health districts12. The community health centres provide primary health care at the community level whereas the referral health centres are secondary care referral centres at the district level. In addition to providing for patients requiring specialty care, the referral health centres support and oversee community health centre activities.

Sampling and recruitment strategy

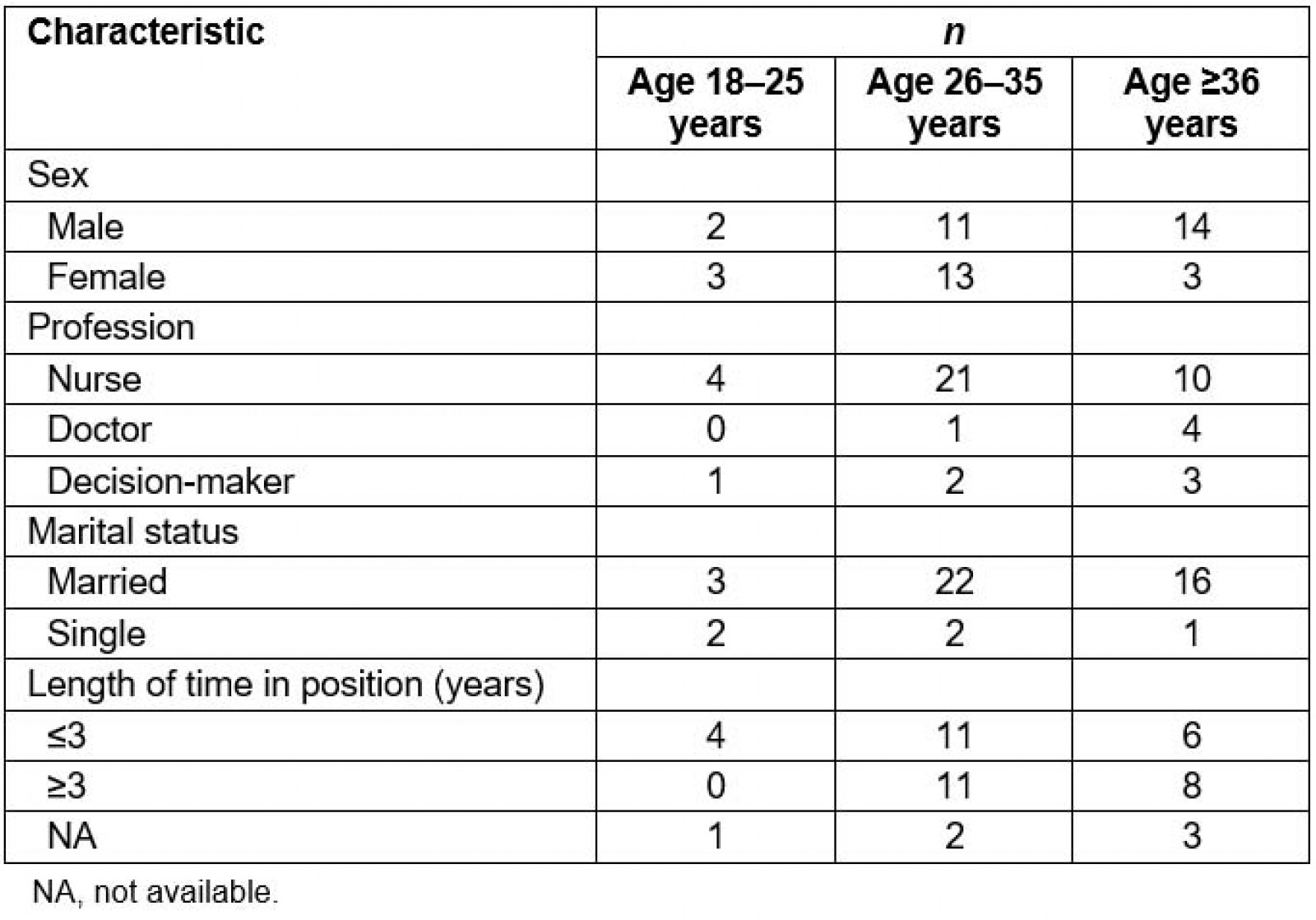

A reasoned sampling was carried out. In this type of sampling, also referred to as non-probability sampling, participants are not selected at random and the sample cannot be said to be representative of the population. Participants with a wide range of perspectives and opinions were purposively selected by the researchers. Empirical saturation (redundancy in the participants’ comments and in the material the researchers were familiar with) was reached after 46 interviews. Researchers interviewed 40 qualified health workers and six national, regional and local decision-makers. At the national and regional levels, human resources managers from the Human Resources Directorate and the Regional Health Directorate were interviewed. At the health district level, interviews were conducted with referral health centre health workers, migrant representatives and administrative authorities. At the community health centre level, one or two health workers per centre were interviewed. Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of the participants. Decision-makers were involved in the recruitment and management of health workers. They include a prefect, a community health association (ASACO) manager, an elected local official and a representative of a migrant association.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of interview participants, by age

Data collection techniques

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to identify and understand the main factors explaining the shortage and poor retention of health workers. A flexible interview guide with open-ended questions was used to conduct the interviews. To better define the research question, interview content was adapted according to participant and information needs. Each interview was conducted by the same two people. One person was in charge of guiding the interview while the other took notes. After each interview, a quick synthesis was conducted to highlight salient points related to the research objective. Interview duration was between 35 and 90 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded using a digital recorder.

Field notes were also collected. Researchers noted thoughts, feelings and impressions during the interviews in order to contribute to a better understanding and interpretation of the data13. These notes also included methodological aspects.

Data analysis

Thematic content analysis was carried out14. The 46 interviews were transcribed in full. The verbatim transcripts were cleaned, formatted and then entered into QDA Miner software v4 (Provalis Research; https://provalisresearch.com/fr/news-events/december-12-2011) for analysis. A mixed inductive–deductive analysis was conducted15. Within each transcript, units of meaning were identified and developed into codes. The codes were then grouped by analogy under subcategories. This resulted in a grid of codes and subcategories that evolved over time. The final subcategories were then grouped according to the categories of factors that influence the attraction and retention of health workers from the selected conceptual framework.

Ethics approval

This study was granted ethics approval by the National Institute of Public Health Research in Mali (14/2017 EC-INRSP) on 3 July 2017. Consent to the publication of the study results was obtained from the MEDIK project. All participants agreed to participate and their anonymity was maintained.

Results

Factors explaining the shortage and poor retention of skilled health workers were classified into four categories: individual-level factors, local factors, work-related factors and national environment factors. No factors related to the international environment were identified in this study.

Individual-level factors

Age, gender and marital status were the main individual-level factors identified by participants. Younger, newer recruits seemed to have more difficulty staying in rural areas for longer periods of time:

The young people who often come to us are not very rooted in the communities. They are placed in a CSCom [community health centre] where there is no telephone network, where you have to work with an ASACO who is the manager. They think they are farmers, it doesn’t work. (District chief physician, district medical officer)

Many young recruits said they were motivated to practise in rural areas to train in community health, of which they had no knowledge before arriving. Some gave themselves a maximum of 3–5 years before returning to urban areas.

Women separated from their spouses faced strong pressure from their partner and partner’s family to return to their homes. This made them less likely to stay:

The ladies don’t want to go to Kayes because the husbands aren’t there. With the public service, distance creates problems. It is the management of female staff that is very difficult. (Manager)

This situation partly explains why the reunification of spouses is one of the most frequently cited reasons for requesting new assignments, particularly for female staff.

Local environment factors

Living conditions, recognition and participation of communities in health were the main factors identified in the local environment. Health workers perceived their living conditions as difficult. For them, there was a minimum to provide for any health worker:

Living conditions are difficult here. Even if we have the money, we don’t even have access to the condiments [spices and vegetables used in sauces]. Condiments are more expensive here than in Bamako. (Technical and clinical director, (DTC))

All health workers in the visited community health centres had motorcycles and dwellings in various conditions, but some had to buy personal solar panels in order to have electricity. For the most part, provided housing or motorcycles were perceived as ‘rights’ and did not contribute to retention:

Well, honestly, I don’t count that. At home, I bought a personal solar panel. I think that all DTCs [laughs] in Mali have a motorcycle and a place to live, eh. (DTC)

Similarly, the majority of participants complained about the long distances and poor road conditions that prevented them from visiting their families, obtaining food and goods, or accessing the populations they worked with:

Under these conditions, if you have a small problem, even a family one, well, it would be solved without you. That’s why, well, I’m trying to leave here [laughs]. (Doctor)

Some participants mentioned access to a quality school and teachers for their children as important.

The recognition of communities and their participation in health was identified by a majority of health workers as important retention factors. Those that got along well with communities and felt well integrated were highly motivated to remain longer:

I get along very well with people and they consider me. For example, I have a good collaboration with the imam or the village chief here, even if I call him now, he will come. It’s motivating. (DTC)

On the other hand, health workers who have a difficult time with communities admit that they do not want to stay, sometimes regardless of the incentives they could be given:

It is only the financial aspect that interests the ASACO. But I’m not going to work and the little money I earn they [members of the ASACO] embezzle, no, I don’t accept that at all. (DTC)

Communities perceive health workers as having better living conditions and, therefore, do not require incentives as recognition. As a result, they charge them more for basic necessities (meat, vegetables, etc.), which is perceived by health workers as a lack of recognition.

Work-related factors

Several participants mentioned the dilapidated state of infrastructure and equipment, problems with the supply of medicines, lack of access to training, staff shortages, interpersonal dynamics, and leadership effectiveness and supervision as important factors influencing retention in rural areas.

Health workers have expressed dissatisfaction with the poor quality of equipment and buildings in health centres. In some community health centres, consultations or deliveries required flashlights at night:

The building is aging. If it rains, there is a part where the water comes in and the maternity room is really small, you can’t have two simultaneous deliveries in there. (Obstetrician nurse)

Inadequate supply of drugs was also recorded. This was related to procurement difficulties due to the isolated location of the community health centres or poor inventory management by the ASACO. Health workers received several continuing education courses, which are perceived as very attractive and meeting their needs. This is also an important source of income. For new recruits in particular, it enabled them to quickly feel competent in their positions within the community health centres:

With the multitude of training courses, I know that I am now up to the task, I am now proud of myself, technically and culturally. (DTC)

A large majority of health workers planned to return to school as soon as possible to obtain a higher diploma in order to progress in their careers and earn a better living. For most, it is the most effective way to leave this difficult region permanently:

I want to go to school to become a midwife and leave here ... I have already submitted my application for the next competition. (Obstetrician nurse)

Several participants pointed out that the shortage of staff leads to a work overload that prevents them from taking their annual leave:

There is no day off for us here, we work night and day. Whenever the population needs health services, we are there to provide them. (DTC)

The workload did not allow them to carry out other activities outside work and some felt exhausted. In addition, the shortage of staff required health workers to be more efficient, which, paradoxically, contributes to retention.

Several health workers admitted that good relations between them, as well as with their superiors, would keep them in their positions. However, relationships with unqualified local staff were often strained. The local staff were often described as ‘politicized’ and ‘infiltrated’, reporting to the ASACO and communities on how the DTC manages the community health centres:

Unskilled personnel are recruited locally. These are political recruitments. So they act like a community antenna reporting everything that the DTC does. (DTC)

Several health workers recognized that management leadership is a major factor in attracting and retaining employees. They appreciated having their leaders protect them in the event of problems with the ASACO or mayors:

It’s thanks to him [chief medical officer] that we’re all here, otherwise, if he leaves [laughs], everyone will leave, because he’s the one who really encourages us to stay here. (Nurse)

Health workers receive several supervisory visits, seen as a source of motivation.

National environment factors

The recruitment and assignment process and insufficient financial incentives are the main factors cited by participants as explaining the shortage and poor retention of health worker in Kayes.

The recruitment and assignment process of health workers (civil servants and contract workers) differs and contributes to certain disparities in their distribution between districts. The recruitment of civil servants is limited by budgetary constraints and managed at the national level, which is perceived as a factor of instability. Civil servants are able to choose their assignment after a 3-year stay in the region of Kayes, which makes them more mobile compared to contract workers. Finally, many feel pressure from their families to leave the region, especially women who are separated from their husbands:

If you recruit in Bamako, for very remote localities, they [agents] are more moved by the idea of civil service, they do some time in the bush and then they will move heaven and earth to go elsewhere. (District medical officer)

A large majority of health workers did not choose their current place of work. The assignment process is perceived not to be very transparent or fair, particularly district assignments managed at the regional level. Indeed, as a result of strong political or social pressures, some ‘privileged’ agents are assigned to districts with better living conditions:

There’s a lot of pressure at the regional level. We do not receive more than two, three or five health workers. (Manager)

In an attempt to maintain basic staffing, after a health worker is posted in the region of Kayes, leaving is difficult. Workers must await replacement, which is very difficult to obtain. This ‘coercive’ measure prevents massive departures of health workers in districts that receive few. However, this harms health workers who wish to leave. To bypass this directive, there is an informal ‘traffic’ network. For many participants, this is the only way to leave the region:

I was posted here in 2013. I asked for a transfer. It was refused by the supervisor. Transfers are very difficult. (Midwife)

If you don’t receive [a health worker], you can’t get rid of what you have ... How can I let them go? (District medical officer)

Assignments between community health centres in the same district are rare, thus favouring staff stability. They are based on the needs and experience of health workers, a well appreciated approach:

The living conditions of agents are often very difficult. It is therefore not necessary to integrate the difficulty of ‘instability’. Staff often need a little insurance. (Prefect)

The recruitment of contract workers is done at the health district level by the ASACOs and town halls through mutual agreement. The disparities between districts can be explained by the level of mobilization of financial resources, which in turn depend on the vitality of the ASACOs and town halls:

A CSCom that is busy generates a lot of resources, and the ASACO may be able to recruit staff. (ASACO manager)

However, contract worker assignments are very rare because contracts are local. This contributes to making some health workers feel as if their situation is transitional and is not well perceived:

If I have a steady job, I’ll leave. Ah! That’s for sure, though. (Contract nurse)

Civil servants are paid according to a national salary scale. Contract workers negotiate their salaries, which are lower than those of civil servants. This was a source of frustration and many health workers felt that their salaries did not allow them to cover the costs of living, and did not compensate for the efforts and sacrifices made:

It’s a heavy responsibility we have. But, we are not really rewarded. (DTC)

In addition to their salaries, several health workers said they received allowances from the ASACO, daily allowances (US$8–25 per day) for training and vaccination campaigns, but also informal financial incentives (under the table, embezzlement, etc). Like salaries, the monthly allowances (US$16–83) allocated by the ASACOs were considered to be insufficient. Other financial incentives included discounts on consultations and deliveries, and paid overtime work:

Saturdays and Sundays are for us. Now, even out of hours, for example, from 2 p.m., any sick person who comes outside of childbirth, that’s for the DTC. (DTC)

These financial inputs were highly appreciated and varied by location. They allowed some agents to save their salaries in order to invest in their home communities. However, most of these financial incentives were perceived as a right, regardless of posting location. Also, many health workers said that nothing could retain them in their current positions because of other issues (family related, with communities) or because of their personal ambitions, incompatible with remaining in their current position (eg desire to continue their studies, to pursue career goals or improve their financial situations).

Discussion

Factors in shortage and retention of health personnel

This study’s results, like those of other African studies, highlight the multifaceted nature of the factors and challenges related to the shortage and poor retention of skilled health workers in rural and remote areas. First, female staff, particularly when married, have specific constraints that prevent them from deploying to or staying in rural areas for long periods of time without their husbands. In Mali, as in several other African countries, it is the norm for married women to reside alongside their husbands and parents-in-law, often at the expense of their careers. In addition, according to the Malian family code, it is the husband who must decide on the family’s place of residence. As a result, married women often seek work where their husbands and extended families resides16. Several authors have found that health workers who grew up or studied in rural areas tend to return and remain longer in these areas17,18; however, the present study’s results did not show this to be true in the region of Kayes. Health workers from this region tend not to want to work there because of the heavy regional social security charges, which prevent them from saving and investing for their future. These findings differ from those of another Malian study that showed rural origins is a factor associated with the recruitment and retention of health professionals in rural areas19.

The living and working conditions of health workers in rural Africa have been mentioned by several authors. These factors were found to be equally important in the present study. Attractive factors included access to decent housing, potable water, electricity, quality schools, telephone, roads and transport20,21. Good workplace interpersonal dynamics and leadership, access to training, community recognition and community participation in health were also found to positively influence attraction and retention22,23. These studies also showed that the dilapidated state of infrastructure and equipment, and the difficulties in obtaining medical supplies, were less attractive.

At the national level, the total number of health worker recruited was described as unpredictable and insufficient to cover needs due to budgetary constraints, while recruitment and assignment procedure was perceived as inequitable and not very transparent. However, failure to comply with the relevant national regulations would disadvantage rural and isolated health structures. Similarly, it appears that public servants were given preference over contract workers, who felt they were in their positions temporarily, while they waited to join the public service. The status of ‘civil servant’ proved to be more attractive for workers as it allowed greater access to mobility, better wages, training and job security. Similar challenges have been identified in other African countries such as Sierra Leone22 and Senegal18, where non-compliance with rules governing health workforce assignments and patronage are a source of demotivation, and hinder attraction and retention of health workers. Studies in Niger5 and Ghana24 found that lack of adequate financial compensation had a negative impact on the attraction and retention of health professionals in rural areas. A systematic review of factors motivating health workers in developing countries highlighted the importance of supporting career plans and providing continuing education and training20. In a Kenyan study21, critical retention factors for health workers were adequate training, job security, wages, supervisor support and a manageable workload. Similar to the present study’s findings, training activities were perceived by Ugandan health workers as a means of obtaining financial compensation, in addition to building capacity25.

Facilitating deployment and retention of health personnel

Results of the present study indicate that a variety of strategies or policies could be explored simultaneously to improve the availability and retention of health workers in rural and remote areas in Mali.

First, strategies should take into account certain social norms to facilitate the retention of married female staff in rural areas by avoiding the separation of spouses. For example, spousal relocation, regardless of gender, could be considered for civil servants wishing to be reunited with their families.

Second, implementing measures to improve the living and working conditions of health workers in order to make them more acceptable has been recognised by several authors as an important measure for attraction and retention26,27. Thus, factors influencing living and working conditions under the responsibility of the Ministry of Health (infrastructure, equipment, access to potable water and electricity) could be improved more easily than those requiring the mobilisation and synergy of multiple sectors (eg roads, transport development). Continuing education and training programs must be maintained as a powerful motivating factor, providing access to knowledge and supplementary income26,27.

Third, the national and regional health workforce management should be strengthened in order to achieve greater equity and transparency, thus reducing the current sense of inequality. Decentralisation of workforce management to the regional level and computerisation could also favour an equitable distribution of human resources and transparency. Similarly, local and priority recruitment into the public service of contract workers currently working in rural areas would increase the value of these experiences and is likely to improve recruitment and retention of health workers in those areas. Work experience in rural areas could, for example, be proposed as a condition for promotion or for obtaining training grants18. Other authors have also proposed orientation modules for new recruits or internships with an elder (as is the case in Bafoulabé)18. As proposed in a Ghanaian study, financial incentives are quite valuable and could include wage increases and the introduction of remoteness allowances to improve the purchasing power of rural health workers24. For example, a study conducted in South Africa by Kotzee and Couper found that improving rural physicians’ salaries would be one of the most important interventions to attract and retain them in rural practice28. In Mali, there are zone bonuses for health officials, but they are very modest and could be increased to generate more pull. However, the present study’s results reveal that financial incentives could only contribute to the retention of health workers if other conditions are met.

Reflexivity

The interviews were conducted by a Malian sociologist and public health doctor who are not originally from the region of Kayes and do not work there. Co-authors who work in the region did not participate in data collection or analysis. Despite these precautions, explanations and assurances, it is possible that there may be a social desirability bias (ie participants expressed what they perceived to be appropriate or socially desired responses). Researchers also questioned the reasons for participating in this research, and it is possible that some participants may have seen it as an opportunity to draw attention to their living and working conditions despite being provided with clear information about the nature of this study.

Limitations

This research is one of the few studies of factors explaining the availability and retention of qualified health workers in rural Mali, and it proposes potentially promising solutions or strategies. Its main limitation is that it is a qualitative study; therefore, it is not possible to generalise these results beyond the two districts in which the data were collected. Nevertheless, the data collected were remarkably similar to those of other studies in sub-Saharan Africa and reflected the difficulties identified in making qualified health workers willing to work and remain in rural and remote areas. Conclusions could therefore be transferable to other contexts with similar characteristics. In addition, the objective of this study is not to make statistical inferences, but rather to gain an in-depth understanding of why rural and remote areas are not attractive to qualified health workers, in order to propose relevant strategies to rectify the situation.

Conclusion

This study identified several factors explaining the shortage and poor retention of skilled health workers in rural and remote areas of the region of Kayes, Mali. These included individual-level factors (gender, family situation and age), difficult living and working conditions, strained relationships with communities (lack of recognition and participation in health), quality of leadership, an unfavourable recruitment and placement process, and insufficient financial incentives. Taking these factors into account would make it possible to combine several high-potential strategies to improve the availability and retention of skilled health workers in these rural and remote areas. Furthermore, these strategies sometimes involve several actors outside the health sector, requiring additional efforts for their implementation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Genevieve Rouleau of the Montreal International Health Unit for reviewing this article.

References

You might also be interested in:

2016 - Towards understanding the availability of physiotherapy services in rural Australia

2010 - Analysis of enhanced pharmacy services in rural community pharmacies in Western Australia