Introduction

Asthma is a chronic disease involving airway inflammation associated with reversible airway narrowing and obstruction in response to diverse and unrelated stimuli or disease. Primary care is essential in reducing asthma-related hospitalisations through illness prevention, controlling acute presentations, and overall management of this complex disease1. At times, asthma exacerbations can require emergency medical treatment at hospital; from a large emergency department through to smaller rural emergency facilities. In non-urban areas, access to emergency health care can vary greatly, with few alternatives and these often servicing a population with poorer health2. This is a situation seen across the globe, one that may actually be worse than reported due to a paucity of data3.

In the state of Victoria, Australia, asthma hospital separations (admitted patient episodes of care), were as high as 3.1 separations per 1000 population in 1993–944, decreasing to 1.74 per 1000 population in 2014–151. Between 2010 and 2015, rates for children aged 0–14 years were as high as 6.88 and 13.76 hospital separations per 1000 population for females and males respectively. Rates were highest among metropolitan males aged 0–4 years, with 15.58 hospital separations per 1000 population, compared to their rural counterparts with a rate of 10.34 separations per 1000 population1.

Although informative, population data and current asthma research in this area only capture self-reported national or state population health survey data, data from hospital admissions, and larger hospital emergency presentation information5. Specifically, emergency hospital presentation data in Victoria are sourced from the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD)6. These data are used for planning, research and policy development. A limitation is that the state-based VEMD only captures emergency presentations from each of the 38 public hospitals across Victoria that have a designated 24-hour emergency department (ED) service6.

ED services in the 38 Victorian public hospitals are defined as being dedicated to providing emergency care, including triage, initial assessment and management of people who are in need of acute or urgent care. As an eligibility requirement, EDs must be staffed on a 24-hour basis by hospital medical staff (on shift or on call)7. These hospitals receive funding based upon activities performed (activity-based funding). Specifically, ED services are required to collect patient level data, also part of eligibility for funding. This is then reported through the VEMD as part of the health service’s overall complex funding arrangements with both the state and federal governments7.

The remaining public health services in Victoria, often in rural areas, provide urgent or critical access services that provide first-line emergency care. In these cases, urgent care centres have capacity to perform emergency resuscitation and stabilisation of patients and, where clinically appropriate, prepare patients for transfer to a higher level of care7. Health services with urgent care centres receive block funding grants to service their community’s need, including emergency care. Because these funding arrangements, which ensure adequate staffing and respective health service goods regardless of actual activity, are not based on the activity-based funding model, reporting patient level emergency presentation data is not mandatory (non-VEMD reporting institutions)7. This may lead to less reliable assessments of rural health care need or performance8. Therefore, although the VEMD data have been used to inform health planning, policy and research concerning the emergency needs of the whole population, in many aspects the gaps in the data remain unknown.

This article, using the Rural Acute Hospital Data Register (RAHDaR)3, which collects and collates both VEMD and non-VEMD data, aimed to determine if a deficit exists in current state-level emergency presentation data, and how this may inform an understanding of childhood asthma in Victoria, while also highlighting the central importance of comprehensive, high-quality data.

Methods

Ten VEMD and non-VEMD health facilities in south-western Victoria, Australia3,9 (equivalent to ‘non-metropolitan’ and ‘rural and small town’ classifications)10 entered into agreements to provide ongoing presentation-level data to the RAHDaR project in return for twice-yearly benchmarking reports. Facilities were classified using known criteria, and two sites continued to also provide mandated VEMD data directly to the state government3.

RAHDaR collates and securely stores data from participating institutions within the South West Alliance of Rural Health, an alliance of public health agencies that provides information technology services. Data remain the property of the hospitals involved, and only de-identified data leave the secure servers3.

All emergency presentations between 1 February 2017 and 31 January 2019 for children aged 0–14 years were included in the data extract from RAHDaR.

All RAHDaR health services were invited and agreed to participate in the study; however, one was unable to provide ICD-10 diagnosis data and therefore was excluded from the study Data fields were based on the VEMD (v22, 2017–2018) where the principal diagnosis was indicated to be asthma-related (ICD-10-AM: J45-J46)11. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyse the data, with significance set at p≤0.05.

Ethics approval

Ethics approvals were obtained from South West Healthcare Human Research Ethics Committee, Federation University Human Research Ethics Committee, and Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (SWH-2019-167534, FUHREC E19-005 and DUHREC 2019-135).

Results

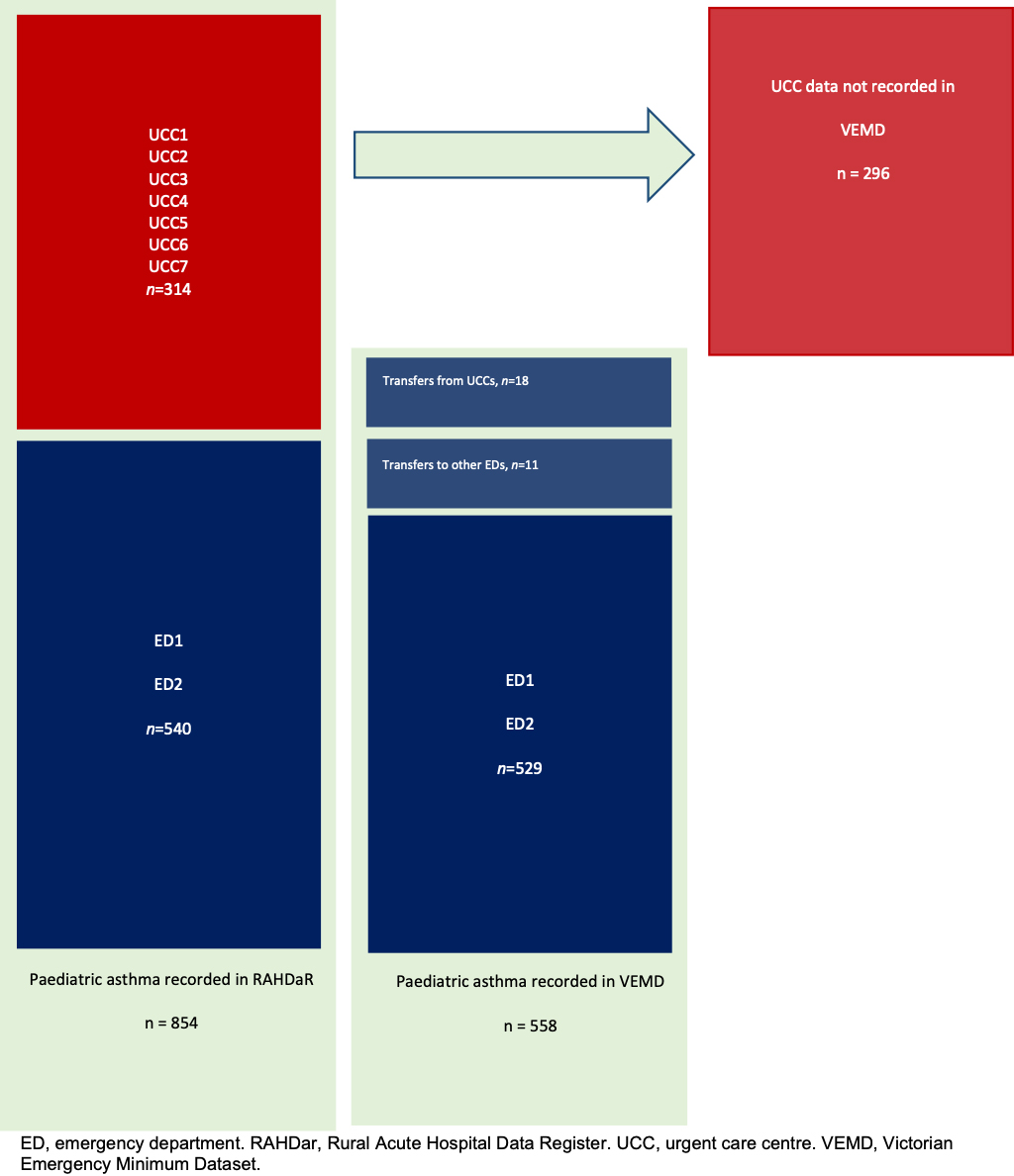

There was a total of 854 presentations of children aged 0–14 years with a principal asthma-related diagnosis among the nine sites participating in the study. A single asthma event may result in several emergency presentations in instances where the child has been transferred between institutions, and this was also captured within the data if the transfer was to another RAHDaR site. A total of 540 (63.2%) presentations were managed initially at VEMD-reporting hospitals (with or without admission); of this cohort, 11 children were transferred to a higher level of care at another institution either in or outside the data catchment area (all VEMD-reporting). A total of 314 (36.8%) presentations were managed initially (with or without admission) at non-VEMD-reporting hospitals, as recorded in RAHDaR (Fig1). Of this group, 18 children who initially presented to a non-VEMD-reporting hospital were then transferred to a VEMD-reporting hospital and had their emergency presentations accounted for in the VEMD through the second facility (either within south-western Victoria or elsewhere). Therefore, a total of 278 (32.5%) emergency presentations do not appear in current government datasets.

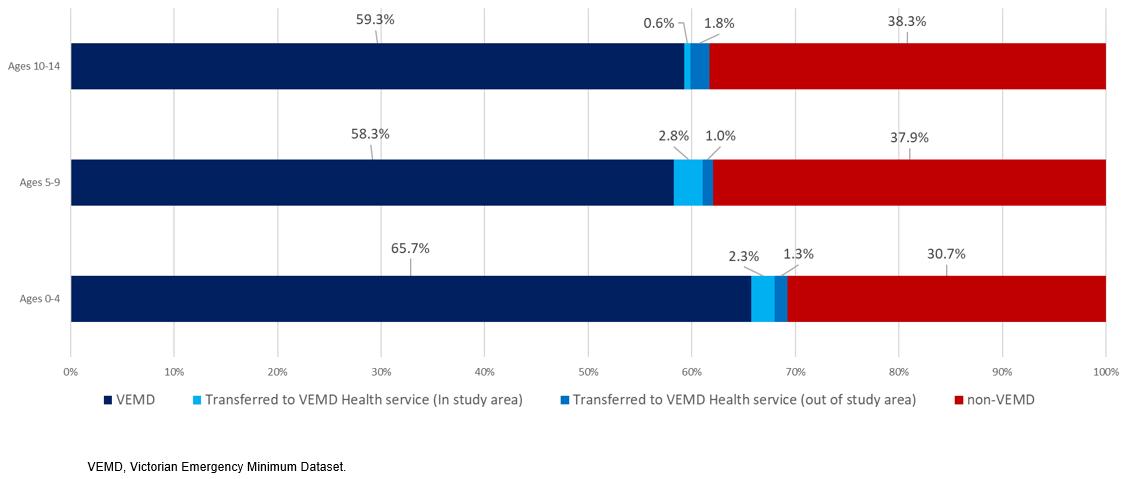

When specifically examining the age groups, it was noted that a lower percentage (30.7%) of children aged 0–4 years were presenting to non-VEMD-reporting hospitals, which increased for the age groups of 5–9 and 10–14 years (37.9% and 38.3%, respectively). This may reflect people, particularly those with younger children, bypassing the local health services for those higher acuity or specialist services9,12,13. Despite this, no significant difference was noted in the proportion of presentations at VEMD- and non-VEMD-reporting hospitals across the age groups, F=(2,29) 0.204, p=0.816 (Fig2).

Figure 1: Emergency presentations for asthma at Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD) and non-VEMD health facilities in south-western Victoria, February 2017 to January 2019.

Figure 1: Emergency presentations for asthma at Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD) and non-VEMD health facilities in south-western Victoria, February 2017 to January 2019.

Figure 2: Emergency presentations for asthma at Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD) and non-VEMD health facilities in south-western Victoria, February 2017 to January 2019, by age group.

Figure 2: Emergency presentations for asthma at Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD) and non-VEMD health facilities in south-western Victoria, February 2017 to January 2019, by age group.

Discussion

This investigation has highlighted a gap in the data concerning childhood asthma, and potentially other disease presentations, that has previously been missed when looking at larger emergency department presentation data alone. Considered in broad terms, RAHDaR has shown that, since the inception, almost 33% of the asthma data for children aged 0–14 years in south-western Victoria is missing from the more readily available VEMD. Although previous work has explored the tendency of the large, urban-focused, administrative datasets to misrepresent the level of activity in small rural hospitals due to its incompleteness14, RAHDaR quantifies the degree of this deficit in the understanding of childhood asthma.

Although national and state-based population surveys and national minimum data sets seek to close some of these gaps in understanding concerning asthma, they remain inadequate to ensure a complete picture is provided, specifically when related to emergency presentations at urgent or primary care services5. Presently, VEMD is missing a significant proportion of the total asthma story when considered in the context of Victoria. As demonstrated here, RAHDaR remains vital in accessing more than a third of the asthma surveillance data that we now know exists through the activity of smaller rural hospitals in south-western Victoria.

Conclusion

RAHDaR’s comprehensive and complete register of data may provide a genuine and more exhaustive understanding of childhood asthma, which represents a portion of all emergency presentations that occur in rural and regional Victoria, yet does not appear in current government datasets. Therefore, more comprehensive datasets may improve asthma management, lead to a reduction in hospital presentations and transfers to larger facilities, or better understand parent decision-making processes when infants and children experience an emergency such as asthma12,13. The findings may also have implications for how services, particularly urgent or primary care services in rural and regional areas, are staffed and funded, and may more comprehensively inform the utilisation of the medical and healthcare workforce in smaller communities. RAHDaR also highlights that what was previously known about asthma rates in rural and regional areas may not provide an accurate representation of what is actually occurring beyond larger health services. This suggests more accurate data from sources such as RAHDaR are essential to fill the now-evident data chasm.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Australian Government through the School of Nursing and Healthcare professions at Federation University Australia, the Centre for Rural Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, Deakin University, and Southwest Healthcare.

Declaration of interest

RAHDaR has been developed by Dr Kloot and Dr Baker at the Centre for Rural Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, Deakin University. We acknowledge that there may be a real or perceived conflict of interest with Dr Kloot as an author of this article.

References

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Suicide and accidental death in Australia's rural farming communities: a review of the literature

2008 - Tele-pharmacy in remote medical practice: the Royal Flying Doctor Service Medical Chest Program

2003 - Male sexual and reproductive health among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population