Introduction

Primary care providers (PCPs) or general practitioners (GPs), along with other primary care practitioners such as nurses, provide the bulk of care for people with diabetes in developed countries with large rural hinterlands like the USA, Canada and Australia. A limited number of studies have investigated access to PCP services among people with diabetes in rural areas in these countries, and few have addressed how individuals at high risk of diabetes access PCP services across the rural–urban divide1.

The goal of the research reported here was to investigate use of PCP services among people with diabetes and people at risk of diabetes using a large survey of people aged 45 years or more (referred to herein as ‘older’ people) linked to PCP use data. Our primary research question asked ‘How different are the access patterns (number of PCP visits) of older people with diabetes and older people at high risk of diabetes in rural Australia from their 'healthy' (without or at risk of diabetes) and metropolitan counterparts?’

Methods

Data

Data were from the 45 and Up Study, a baseline survey of more than 267 112 people aged 45 years or more from New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The survey, mostly administered around 2008, by the Sax Institute, randomly sampled approximately 10.9% of the older population in NSW using the Department of Human Services enrolment database, which provides near-complete coverage of the population2. People aged 80 years or more and residents of regional and remote areas were oversampled by a factor of two. These survey data were linked by the Sax Institute using a unique Department of Human Services identifier to Medicare Benefits Schedule PCP administrative claims data (number of PCP visits made by respondents) and subset to a 6 month window before and after the survey date.

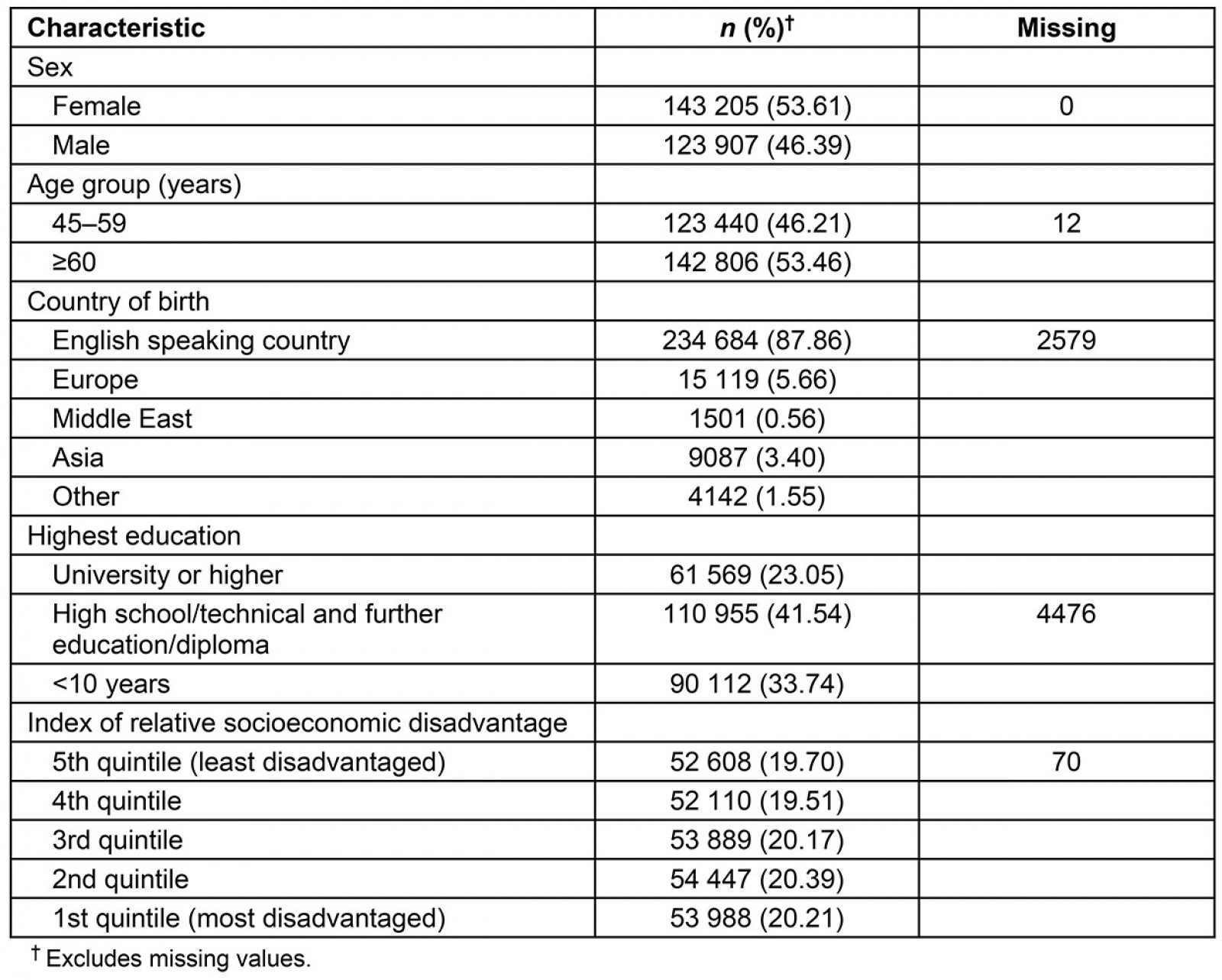

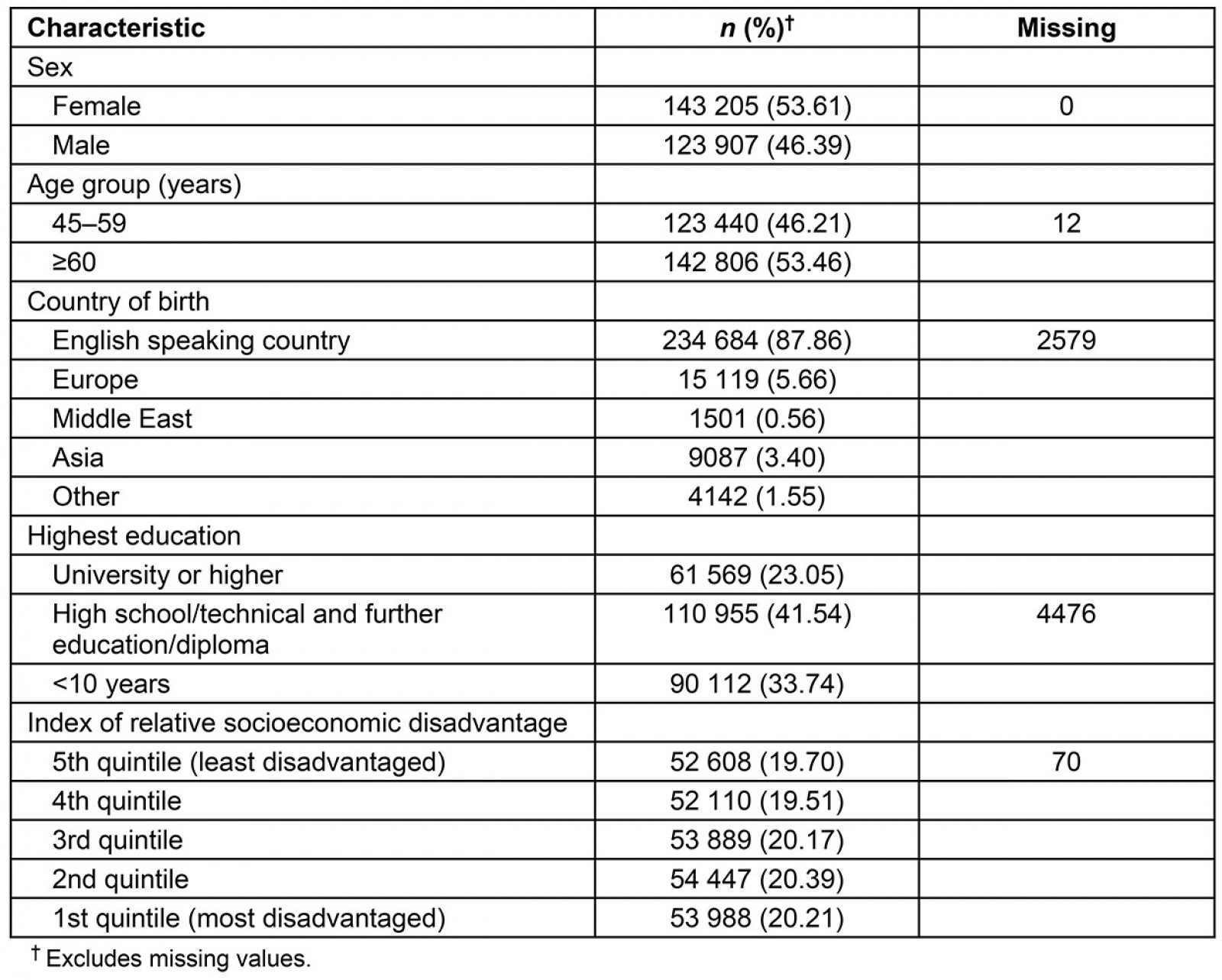

Information was obtained about each survey respondent’s postcode of residence, age, sex, country of birth, highest qualification, whether they were ever told by a doctor that they had hypertension or high cholesterol, whether they had familial heart diseases, the hours they spent sitting or sleeping, their body mass index and smoking patterns (Tables 1, 2). Diabetes status was inferred from the survey question ‘Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes?’, which has been previously validated against external diabetes data3. The postcode was attached to Australian Statistical Geographic Standard rurality codes, which divide the land mass of Australia into five categories with increasing degrees of rurality: metropolitan, inner regional, outer regional, remote and very remote. Of 267 112 respondents, 35 117 were missing various covariates, resulting in a sample of 231 995 (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1: Basic demographic information for study population

Table 2: Health and behavioural characteristics of study population

Categorising respondents

The authors tabulated the average number of PCP visits by metropolitan, regional (both inner and outer) and remote/very remote across three mutually exclusive categories: people with diabetes, healthy respondents and those with diabetes risk factors. The methods of identifying the group with risk factors of diabetes, utilising a previously published model4 are described in Appendix I.

Ethics approval

The Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study was approved by the University of NSW Human Research Ethics Committee. The project was approved by the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (HREC/13/CI/CIPHS/8).

Results

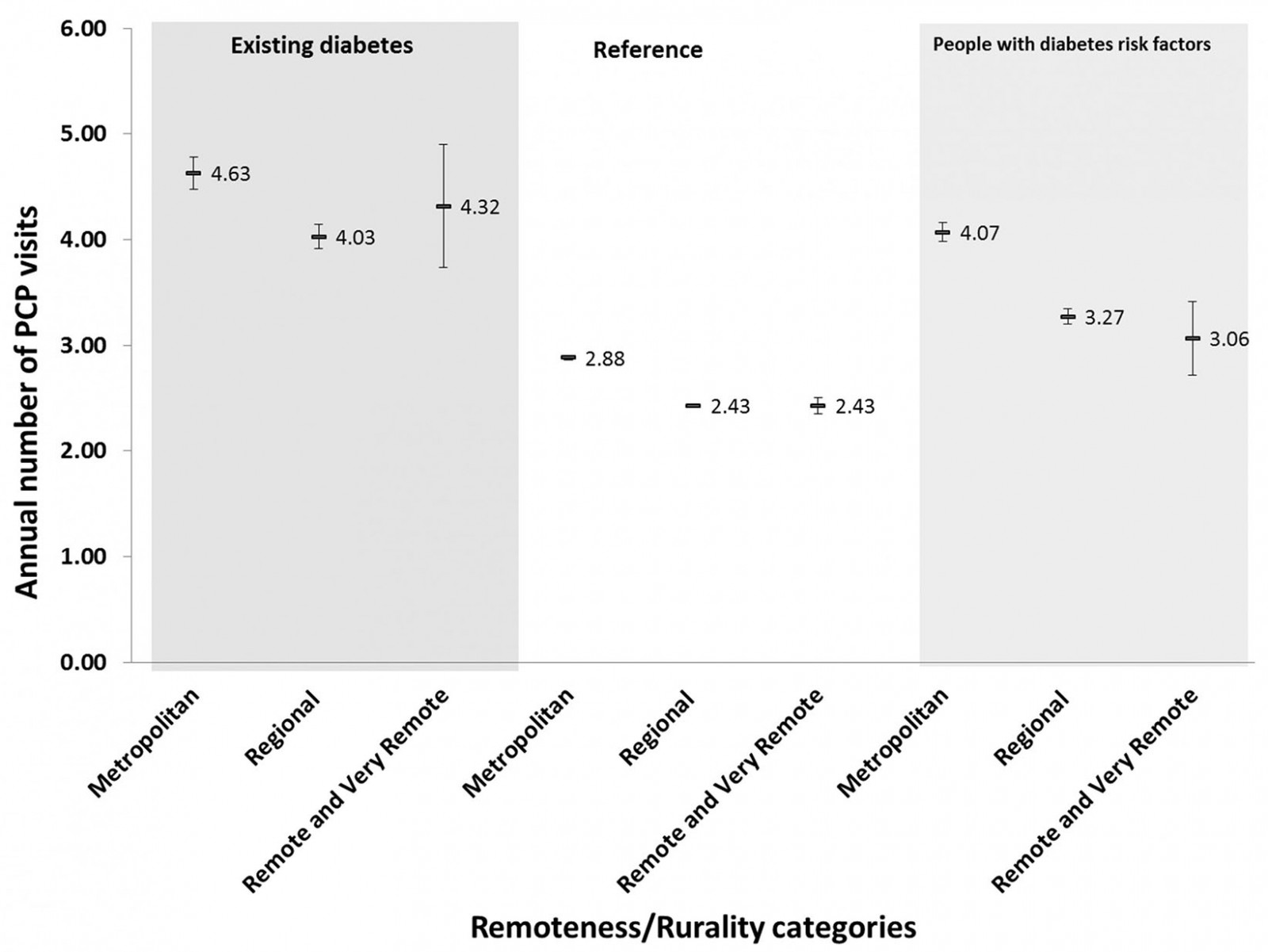

People with diabetes in regional areas made significantly fewer PCP visits than people with diabetes in metropolitan areas (Fig1), although they visited PCPs more regularly than their healthy counterparts in regional areas. Thus, while regional people with diabetes made an average of 0.6 fewer visits annually than their metropolitan counterparts they also made 1.6 more visits annually than healthy individuals in regional areas. People with diabetes in metropolitan areas, in contrast, made 1.75 more visits annually than their healthy counterparts. Indeed, across the board, people in metropolitan areas made more visits, reflecting better access. Those at high risk of diabetes made an intermediate (between healthy people and people with diabetes) number of visits. Large confidence intervals for summary statistics, owing to small numbers from remote/very remote areas, made inferences difficult.

Figure 1: Primary care provider visits among the reference population, people with diabetes and people with undiagnosed diabetes across rurality and socioeconomic gradients.

Figure 1: Primary care provider visits among the reference population, people with diabetes and people with undiagnosed diabetes across rurality and socioeconomic gradients.

Discussion

Access to health services in regional and remote areas is a problem. This study investigated PCP access in older rural people with diabetes – an especially vulnerable group – using data from a large survey from NSW, Australia. The authors found that while people with diabetes living in rural areas visit PCPs less often than comparable groups, they still make about four visits each year, the recommended number for people with diabetes5-7, although it is not known whether the visits are diabetes-related. Older people with diabetes may have comorbid conditions requiring more than the recommended four annual visits. Guidelines regarding recommended number of visits for specific groups – such as older people in rural areas with diabetes – are sparse, and it is likely that they may need more than four visits a year.

A group identified as having many of the risk factors of diabetes visited PCPs relatively often (about four visits each year). This may be because of existing illnesses – some of which (eg high blood pressure) are incorporated in the risk index, and some of which are associated with other risk factors – but again shows similar urban–rural gradient of access, with rural residents making around one fewer visit each year than their metropolitan counterparts. Thus, even if this model of diabetes risk prediction is not accurate, the fact that individuals in rural Australia may be less able to access PCP support to help in the management of their risk factors is a cause for concern.

The authors were unable to find any studies that investigated patterns of PCP use among people at risk of diabetes, but some studies have investigated patterns of PCP use among people with diabetes, reporting rates of use similar to the ones reported here. A study from the USA reported that, in 2011, approximately half of all people with diabetes had six or more office-based physician (who may include specialists) visits annually8. A study from Western Australia reported PCP usage levels among people with diabetes that range from around 2 visits in 10 months to 8 visits in 40 days9. The present results are somewhere between these extremes reported in the Western Australia study.

Conclusion

The strength of this study is that it utilises linked data from a large survey. A weakness of this study is that the survey did not include any clinical data, which may have been used for better risk prediction and analysis and for identifying specifically diabetes-related visits. Nevertheless, it is hoped that this study will stimulate research on PCP access for people with diabetes in rural areas with better quality data.

Acknowledgements

This research was initiated at the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute, which was a key component of the Australian Government funded Primary Health Care Research, Evaluation and Development (2000–2014) Strategy. This research was completed using data collected through the 45 and Up Study (www.saxinstitute.org.au). The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council NSW, and partners: the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NSW Division); NSW Ministry of Health; NSW Government Family & Community Services – Ageing, Carers and the Disability Council NSW; and the Australian Red Cross Blood Service. We thank the many thousands of people participating in the 45 and Up Study.

References

appendix I:

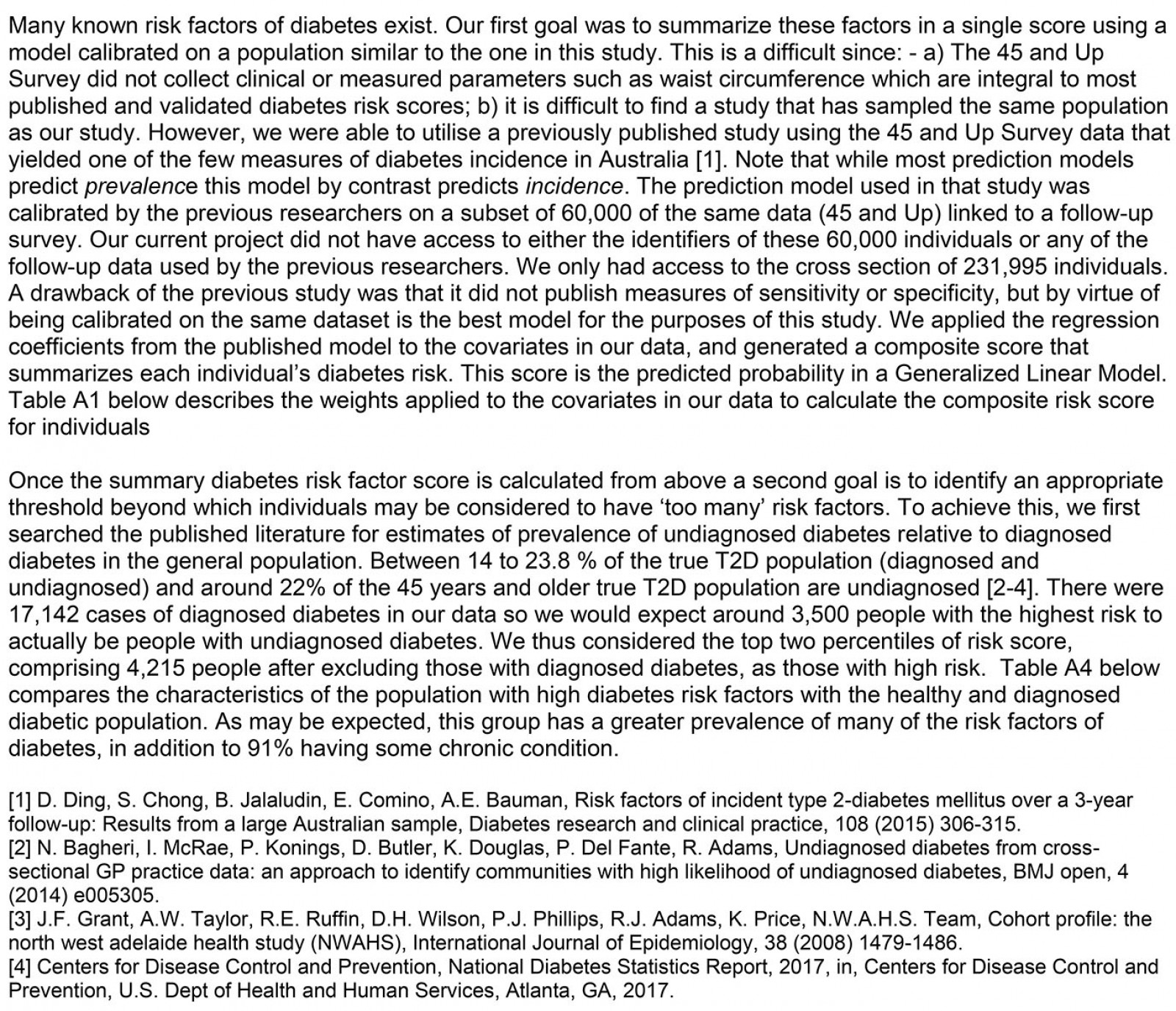

Method of identifying a group with risk factors of diabetes

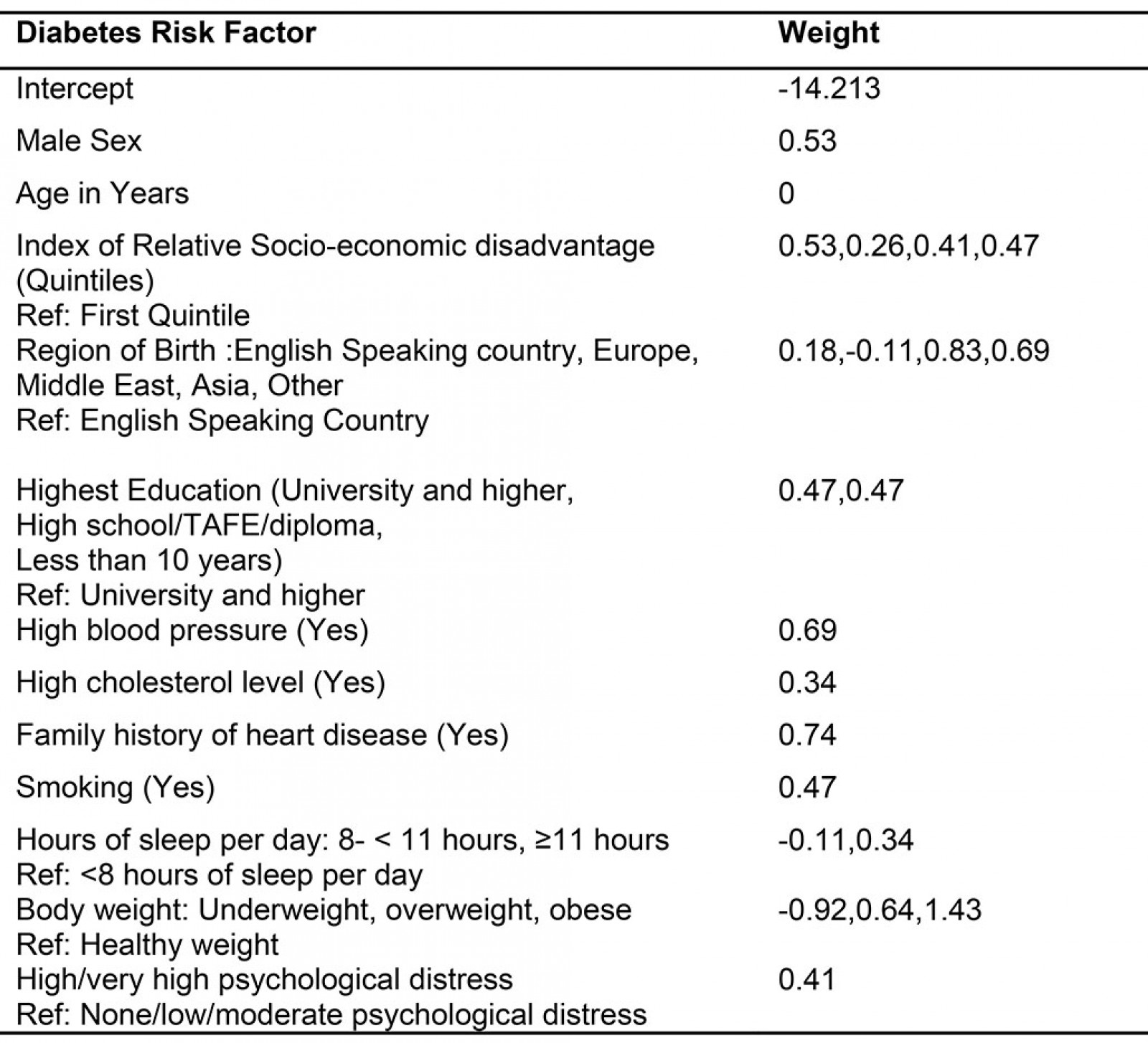

Table A1: Weights of the various risk factors of diabetes used in the model

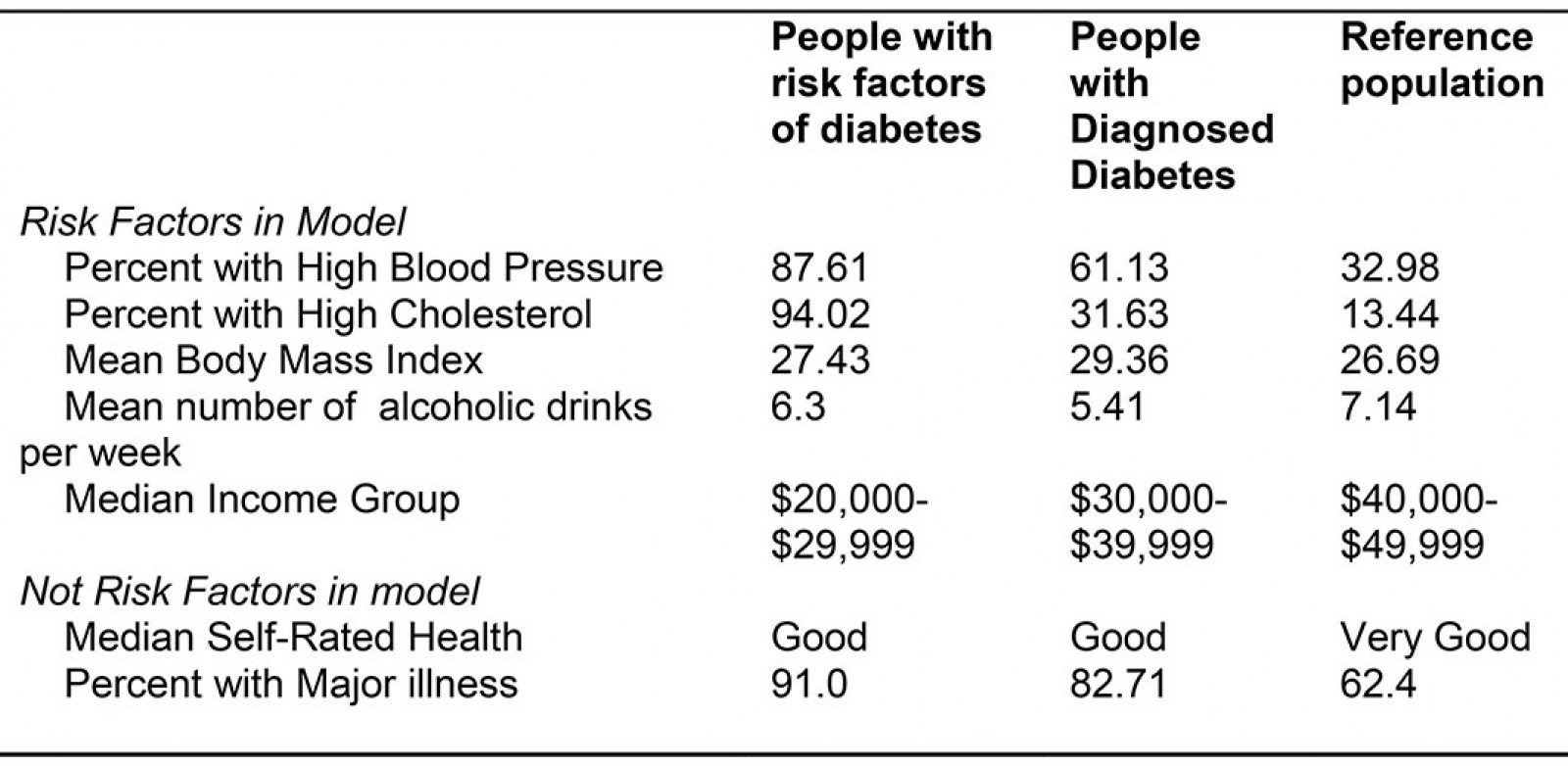

Table A2: Exploring characteristics of people with risk factors of diabetes, diagnosed diabetes and everyone else (reference)

You might also be interested in:

2006 - Medical students' assessments of skill development in rural primary care clinics