Introduction

Projections predict a shortage of nearly 400 000 doctors across the 32 countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2030, estimated at 21.6% of supply in the USA and 22.8% in France1. The shortage in doctor supply is often worsened by geographic imbalances2, which in particular create disparities between rural and urban health care3. This shortage in rural areas is determined by personal, training and practice factors4.

In 2015, the density of family physicians/general practitioners (GPs) was 2.5 per 1000 inhabitants in the USA and 3.3 per 1000 inhabitants in France, with unequal territorial distributions5. In the USA, there was a density ratio close to five to one between capitals and other areas; in France, there were 3.9 GPs per 1000 inhabitants practising in urban areas versus 2.7 in rural areas5. Although rural areas covered 97% of the USA and included 19% of the population in 20166, it was estimated in 2000 that only 9% of all GPs were practising in rural areas7. A similar trend was observed in France in 2012, as only 9% of GPs were practising in rural areas8, which represented 78% of the territory and included 31% of the population9. Because of these disparities in the medical workforce, as well as transportation barriers, patients living in rural areas are exposed to inequalities in healthcare access, insofar as they usually visit a physician less often and later in the course of their illness than urban inhabitants do7,10. In France, priority zones have therefore been defined based on low accessibility to GPs11. These underserved areas represented approximately 6% of the French population in 201812.

In the USA, there are sharp differences between rural and urban inhabitants in the frequency of behavioural risk factors and leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Rural inhabitants are less likely to be non-smokers, maintain a normal body weight, and meet physical activity recommendations13. Rural areas have higher rates than urban areas for many chronic conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, hypertension, high hypercholesterolemia, cancers, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, and depressive disorder14. In addition, mortality rates are higher in rural areas than in urban areas, including for heart disease and stroke, chronic lower respiratory disease, and cancers15,16.

Beyond the differences in the epidemiology of health problems between rural and urban areas, few comparative data are available on GP activities according to their location. For example, in a study conducted in the USA in 1997, Probst et al found that, in rural practice, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular problems were more frequent, whereas clinical preventive services were less frequent17. Unfortunately, such studies were not replicated in other countries.

The aim of the current study was to analyse the activities of French GPs according to the location of their practice: rural or urban.

Methods

This study was ancillary to the French ECOGEN (Eléments de la COnsultation en médecine GENérale) study, which was a cross-sectional, multicentre, national study conducted in French general practice18. Its main objective was to describe the health problems managed in general practice and the associated reasons for encounter and processes of care.

Data collection

Data were collected by 54 interns in training, who acted as observers of 128 GP trainers. Data were initially collected in free text on a paper questionnaire during each consultation, during a period of 20 working days from December 2011 to April 2012. Any patient consulting at a GP’s office or seen at home, and not refusing to participate, was included. Data collected for the patient and the consultation were sex, age, place of consultation (office or home), patient exemption status for low income, consultation length, health problem(s) managed, and the associated reasons for encounter and processes of care performed or planned. Data collected for each GP were sex, age, practice location (rural area, urban cluster or urban area), type of practice (solo or collective), fixed fees agreement (yes/no) and yearly number of consultations. Interns secondarily entered the data into a central database accessible on a dedicated server.

Data management

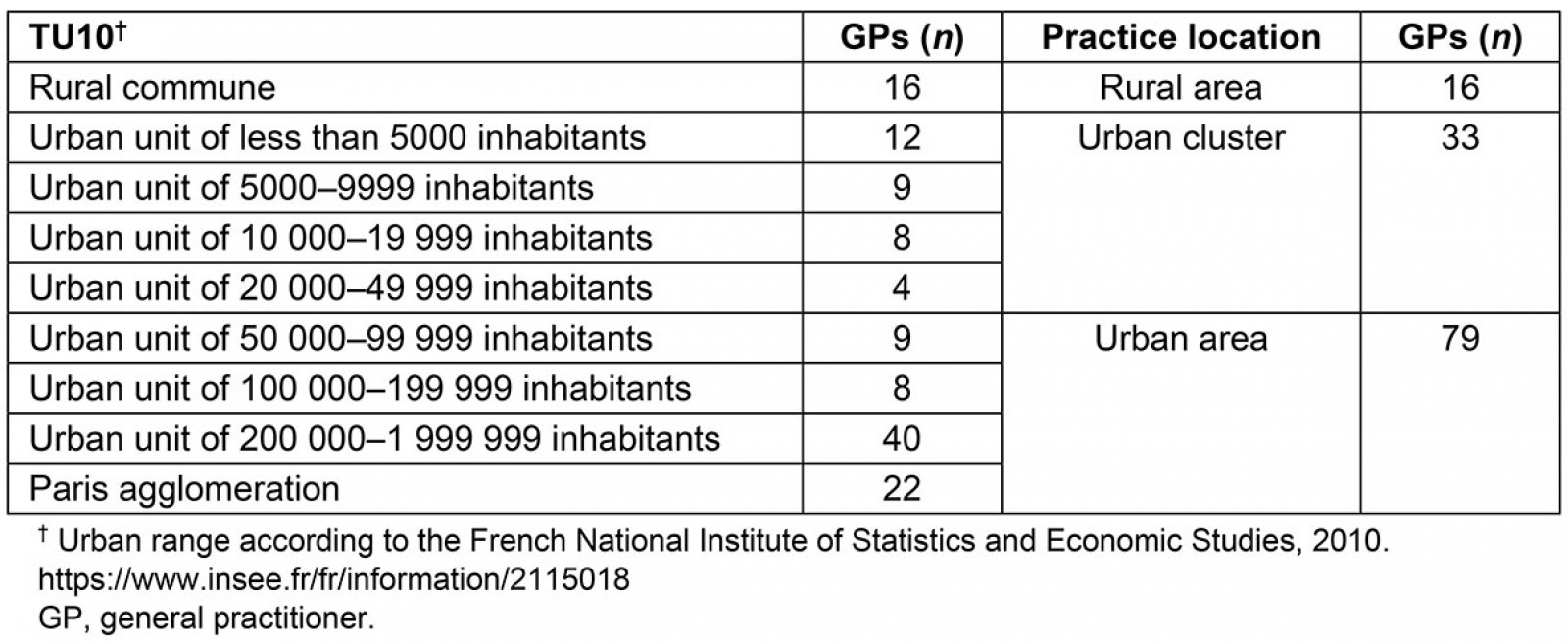

Reasons for encounter, health problem assessments, and processes of care were classified according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2)19. GP practice locations were classified into three categories derived from the classification of the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques, INSEE), based on 2007 census data, using both the name of the commune and the zip code20. INSEE defines an urban space as a commune/district or a group of municipalities, which encompass in its territory a built-up area of at least 2000 inhabitants, where no dwelling is separated from the nearest by more than 200 metres; and each concerned municipality has more than half of its population in a built-up area. By definition, all the remaining communes are classified as rural. In addition, urban communes were subdivided into two categories: urban clusters (ie communes listing between 2000 and 50 000 inhabitants) and urban areas (ie communes of at least 50 000 inhabitants), including the Paris agglomeration (Appendix I).

Data analysis

Data were managed and analysed using SAS software (v9.4, SAS Institute; https://www.sas.com/fr_fr/software/sas9.html). Univariate comparisons were based on χ² tests for categorical variables and variance analyses for quantitative variables. Multivariable analyses were also performed for key dependent variables (GP yearly number of consultations, and consultation length, number of health maintenance/prevention situations, and number of chronic conditions per consultation), using linear regression models. These regression analyses used hierarchical mixed-effect models with random intercepts for physician effect and two levels when appropriate: the physician and the consultation. The threshold for statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Ethics approval

The ECOGEN study was approved by the National Data Protection Commission (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, CNIL; No. 1 549 782) and the regional ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est IV; No.L11-149). Authorisation for the use of ICPC-2 was obtained from Wonca.

Results

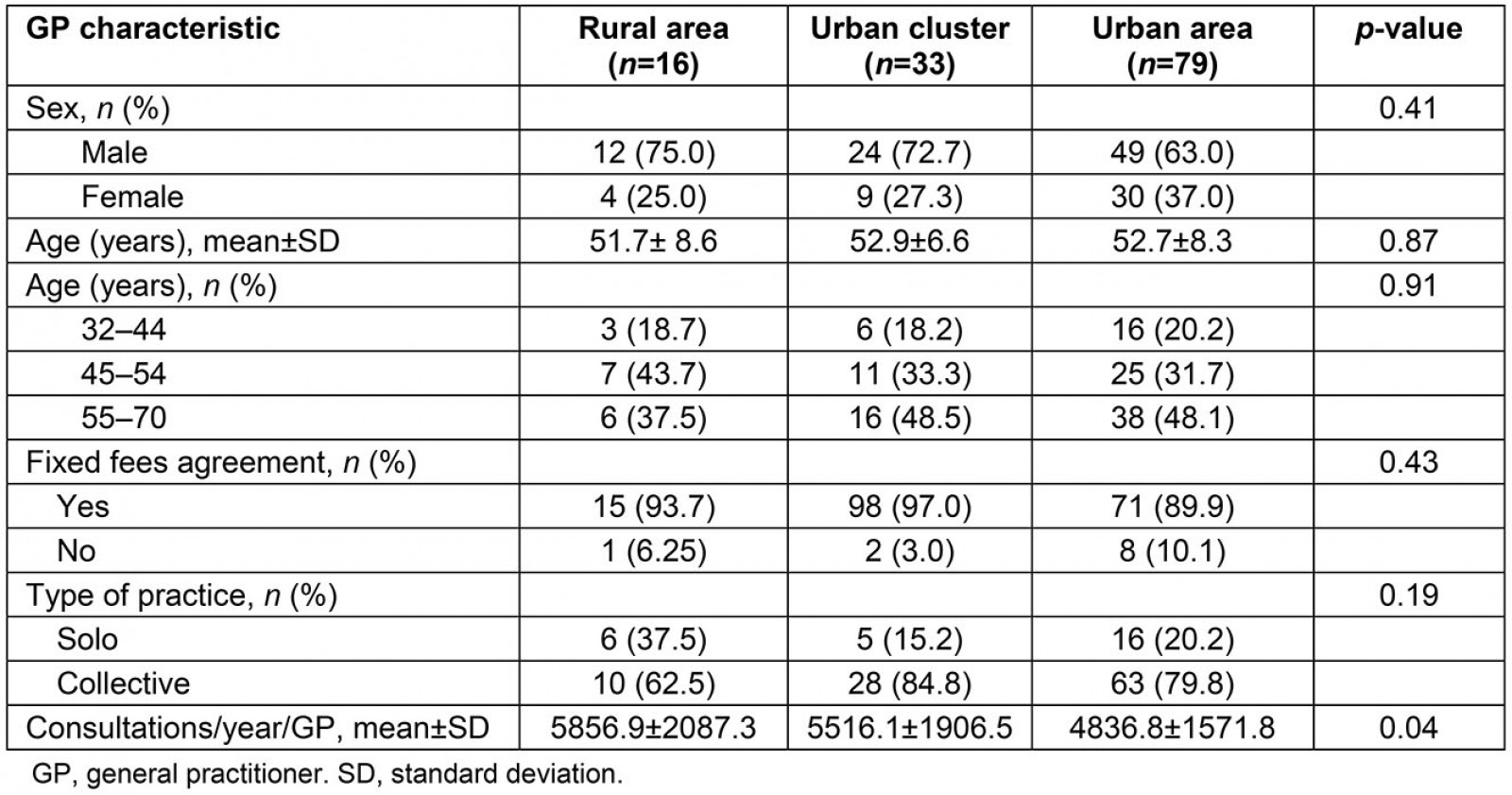

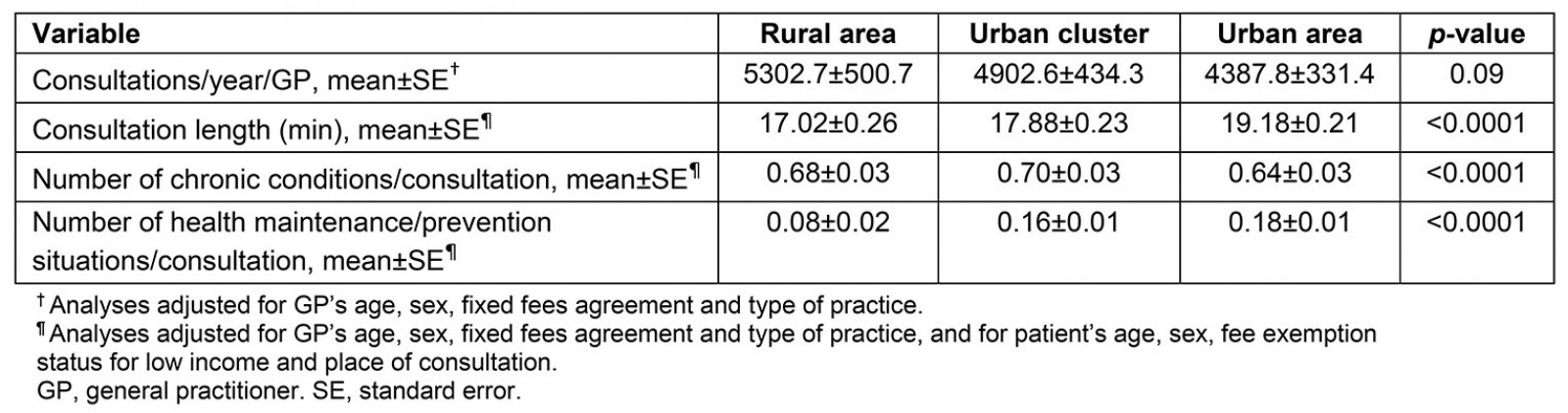

The database included 20 613 consultations. The mean number of consultations per GP per year was higher in rural areas than in urban clusters or urban areas (p=0.04). No difference was found for GP’s sex (p=0.41), age (p=0.87), type of fees agreement (p=0.43), and type of practice (p=0.19) according to practice location (Table 1). In multivariable analysis, the mean number of consultations per GP per year tended to be higher in rural areas (5302.7) than in urban clusters (4902.6) or urban areas (4387.8) (p=0.09) (Table 2).

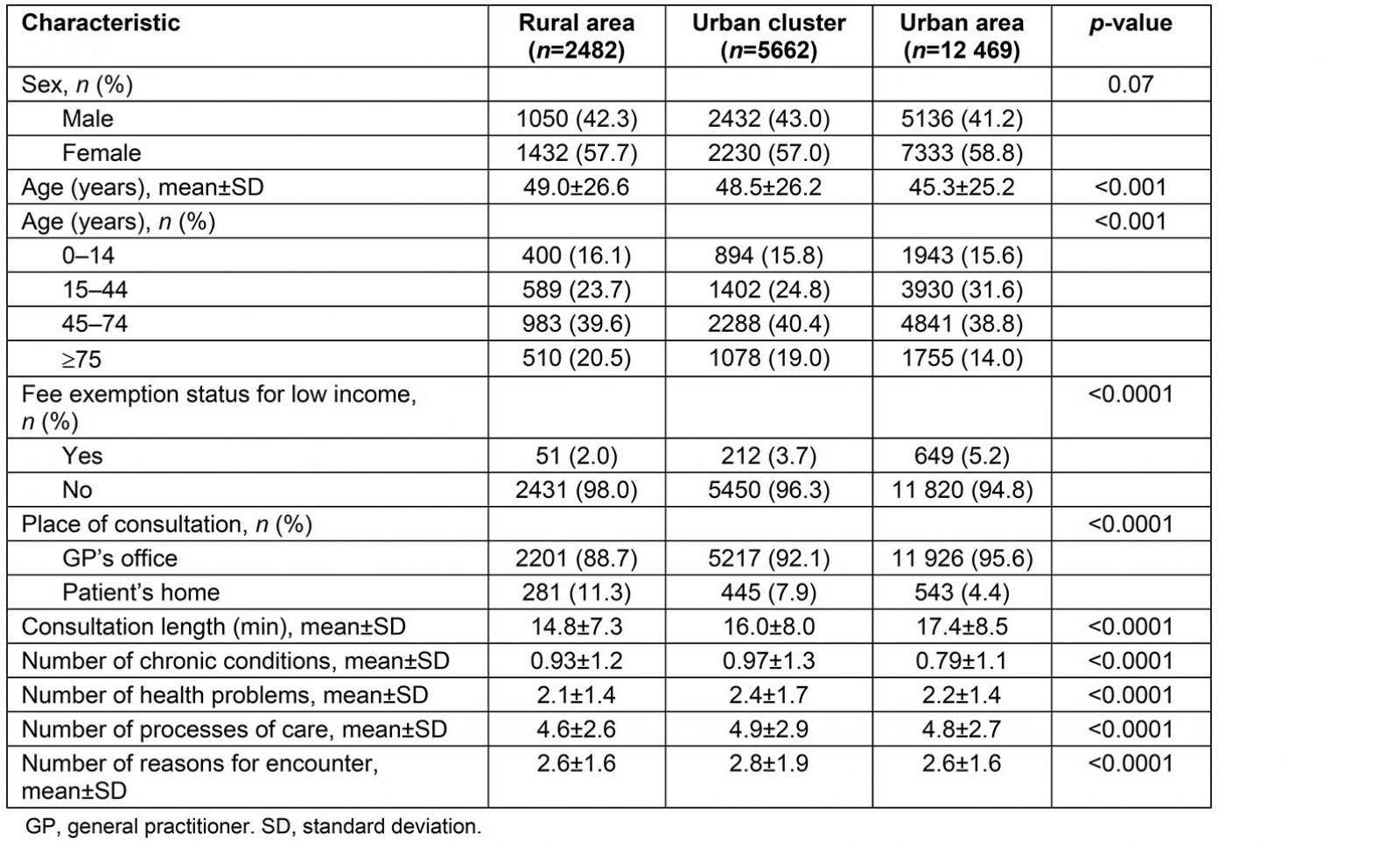

Patients consulting in urban areas were younger than those consulting in rural areas or urban clusters, and there was a lower proportion of patients over 75 years (p<0.001). The sex of patients did not differ according to GP practice location. In rural areas, patients less frequently benefited from fee exemptions, were more often visited at home (p<0.0001), and had a shorter mean consultation length (p<0.0001). The mean number of health problems assessed (p<0.0001) and reasons for encounter presented (p<0.0001) as well as the mean number of processes of care performed or planned (p<0.0001) were lower in rural and urban areas than in urban clusters. The mean number of chronic conditions was higher in rural areas and urban clusters than in urban areas (p<0.0001; Table 3). In multivariable analyses, the mean length of consultation was shorter in rural areas (17.02 minutes) than in urban clusters (17.88) or urban areas (19.18 (p<0.0001); and the mean number of chronic conditions was higher in rural areas (0.68 per consultation) and in urban clusters (0.70) than in urban areas (0.64) (p<0.0001) (Table 2).

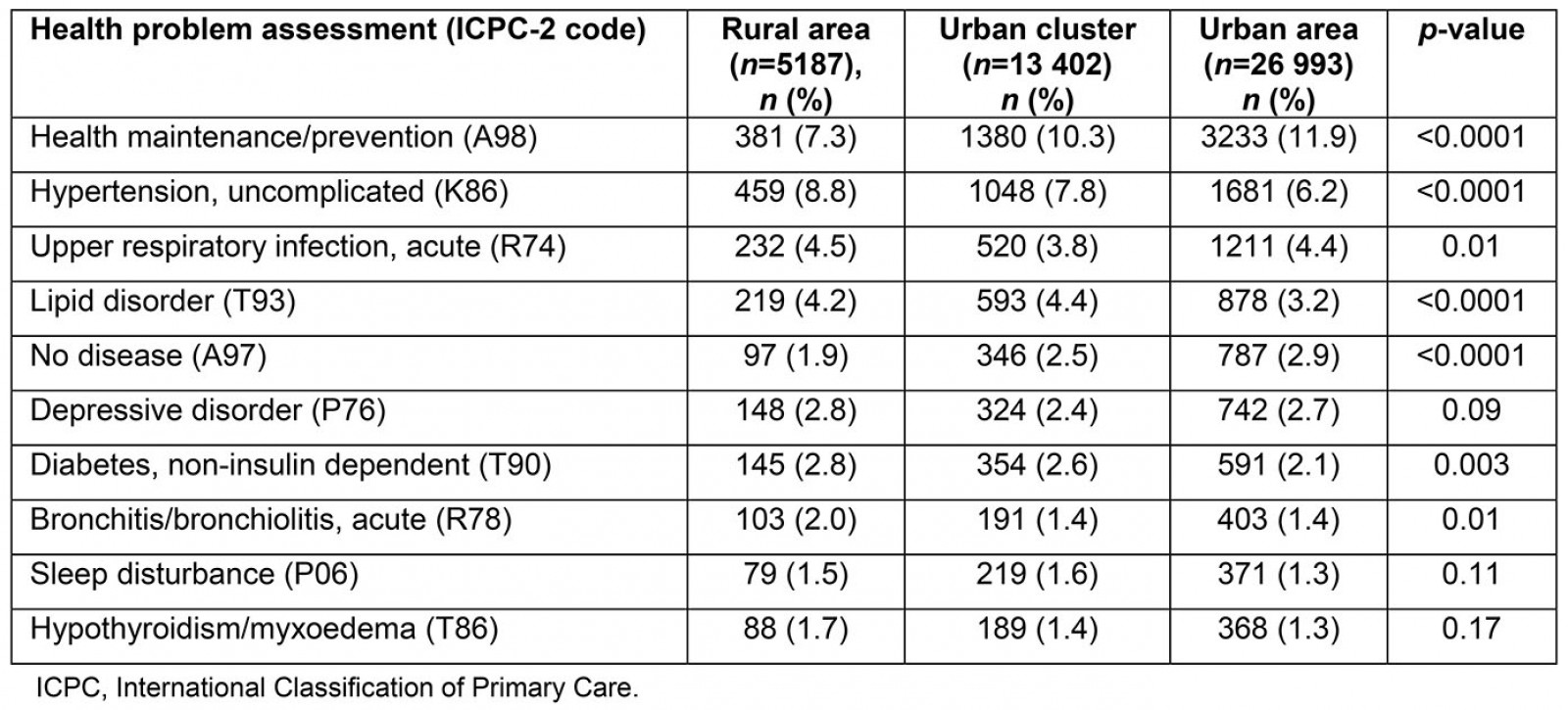

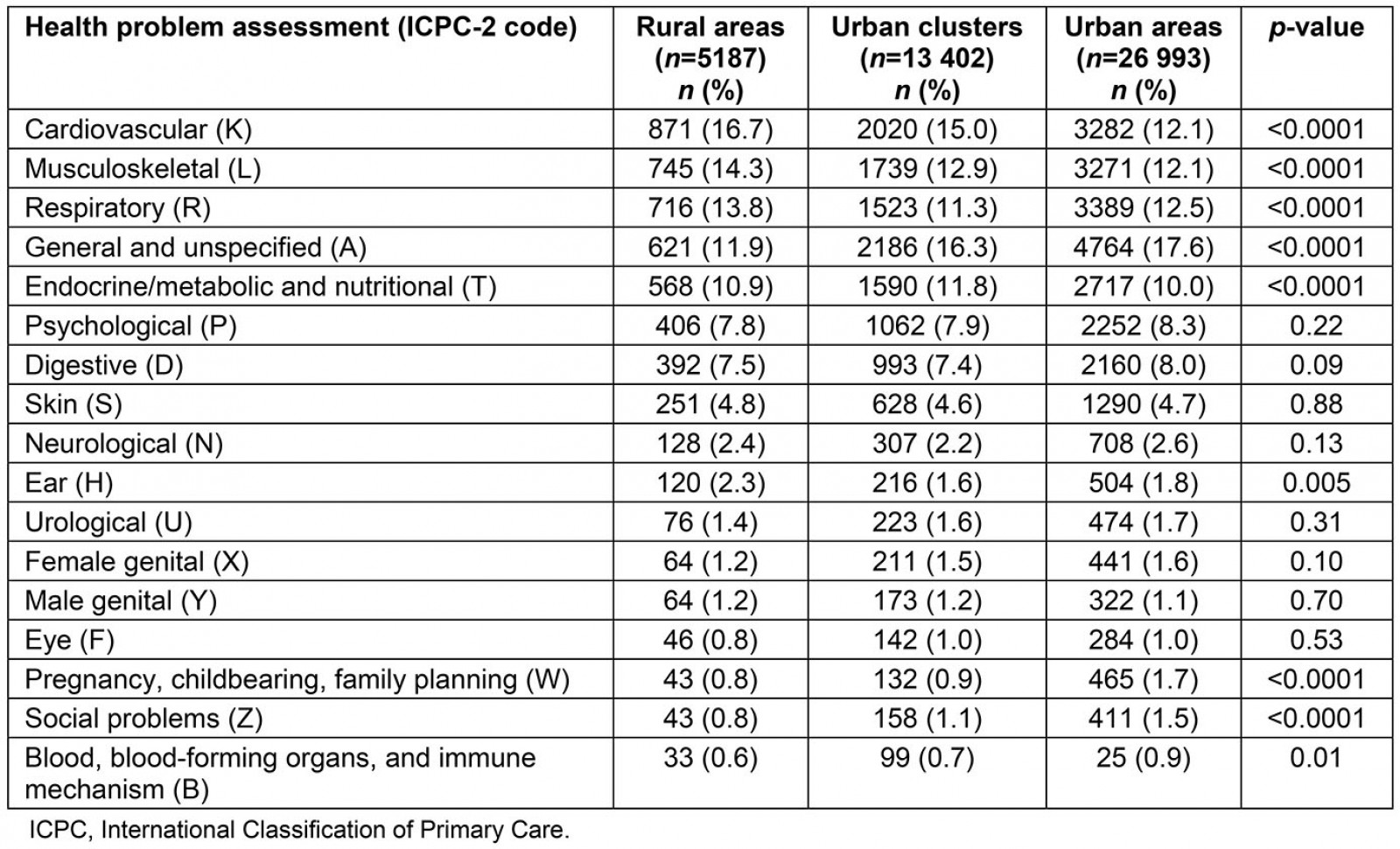

Among the top 10 health problem assessments, hypertension (p<0.0001), type 2 diabetes (p=0.003), and acute bronchitis/bronchiolitis (p=0.01) were more frequently managed in rural areas than in urban clusters and areas. Conversely, health maintenance/prevention (p<0.0001) and no disease situations (p<0.0001) were less frequent in rural areas. The frequency of depressive disorders did not differ according to GP practice location (p=0.09; Table 4). Among the 17 body systems, cardiovascular (p<0.0001), musculoskeletal (p<0.0001), respiratory (p<0.0001), and ear (p=0.005) problems were more frequent in rural areas than in urban clusters and areas. Conversely, general health problems (p<0.0001), pregnancy and family planning problems (p<0.0001), social problems (p<0.0001), and blood and immune problems (p=0.01) were less frequently managed in rural areas and urban clusters than in urban areas (Table 5). In multivariable analysis, health maintenance/prevention situations were less frequently managed in rural areas (0.08 per consultation) than in urban clusters (0.16) or urban areas (0.18) (p<0.0001) (Table 2).

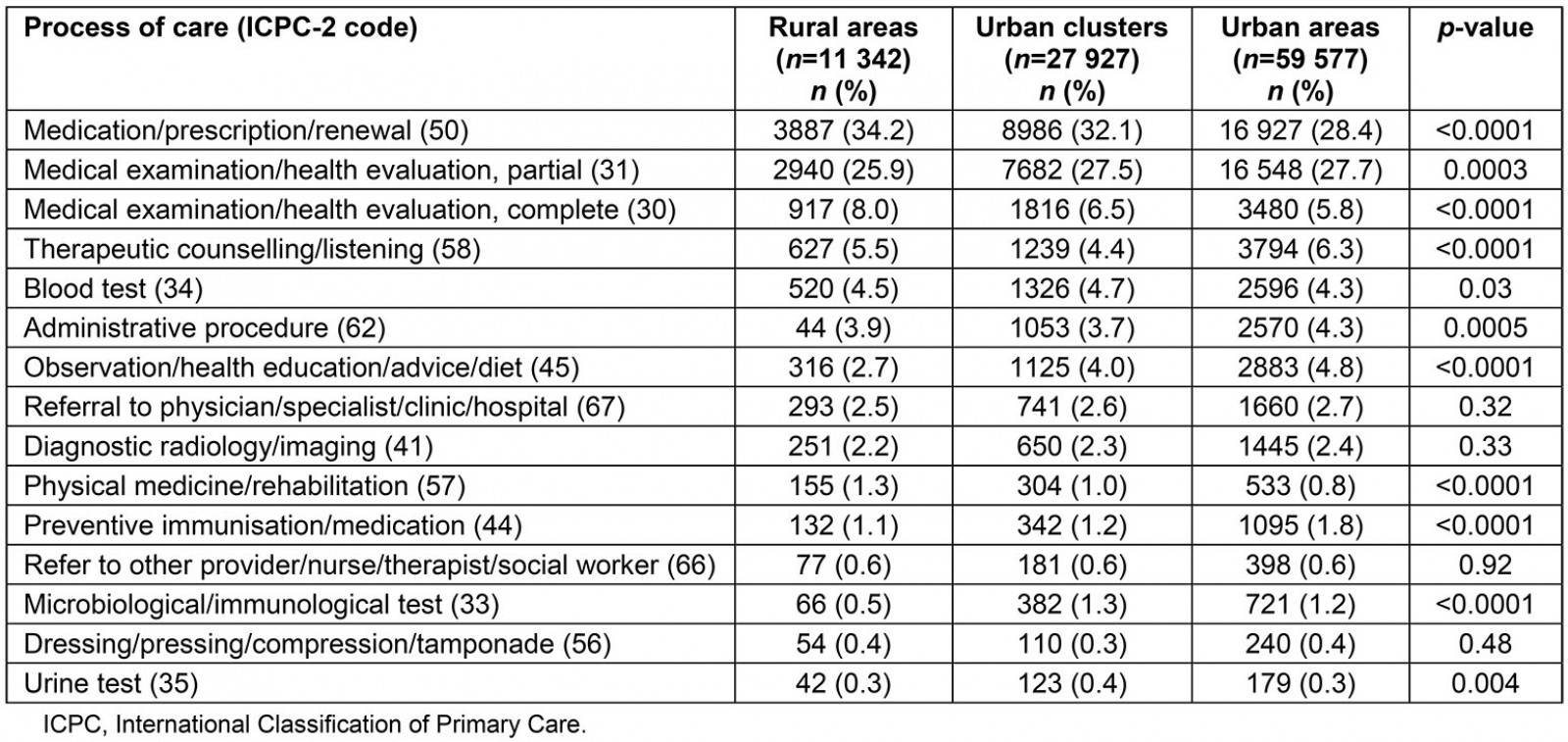

Among the top 15 processes of care performed by GPs, drug prescription was more frequent in rural areas than in urban clusters and areas (p<0.0001). Complete clinical examination was more frequently performed in rural areas (p<0.0001), contrary to partial examination (p=0.0003). Educational processes (ICPC-2 code 58 p<0.0001 and ICPC-2 code 45 p<0.0001), administrative procedures (p=0.0005), and preventive immunisation/medication (p<0.0001) were less frequently performed in rural areas and urban clusters than in urban areas. The frequencies of referrals to a physician (p=0.32) or to another provider (p=0.92), of imaging prescriptions (p=0.33) and of dressings (p=0.48) did not differ according to GP practice location (Table 6).

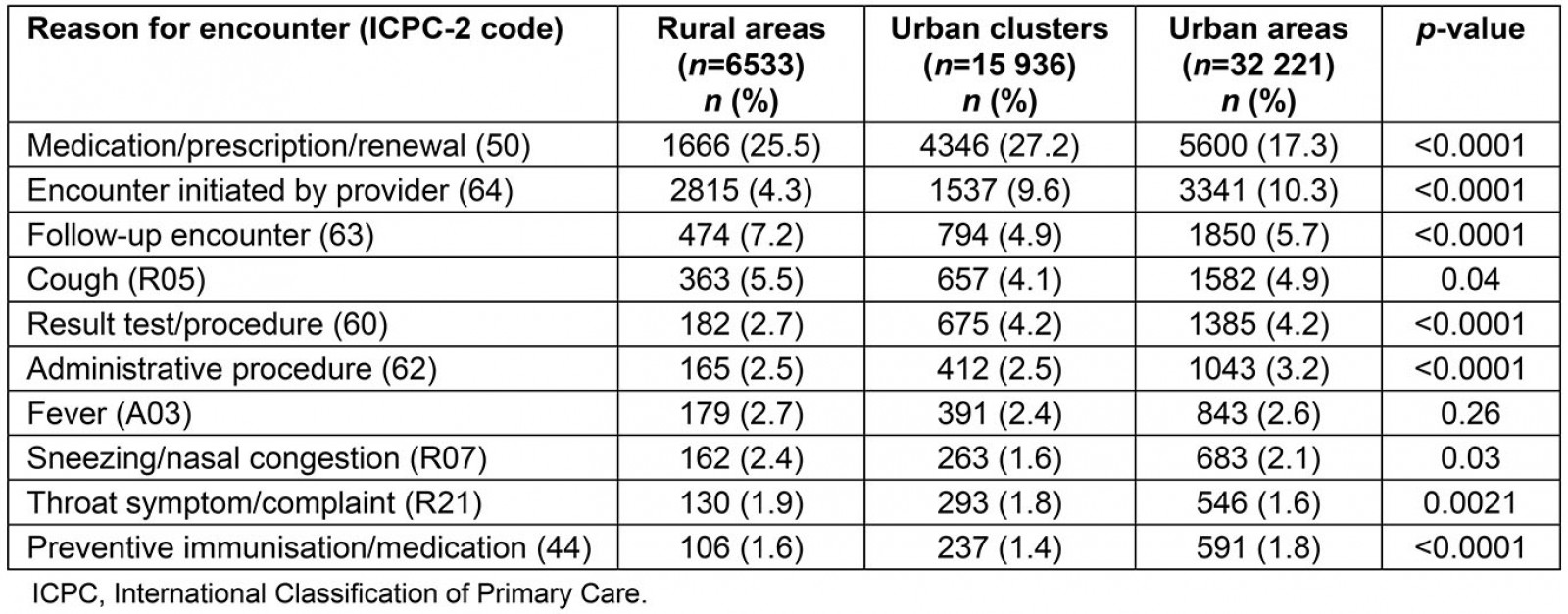

Among the top 10 reasons for encounter, drug prescription was more frequent in rural areas and in urban clusters than in urban areas (p<0.0001). Cough (p=0.04), sneezing/nasal congestion (p=0.03), or a throat complaint (p=0.0021) were more frequent in rural areas than in urban clusters or areas (Table 7). The health issues managed during the consultation were less frequently raised by the GPs (p<0.0001) and the encounter more frequently concerned follow-ups (p<0.0001) in rural areas.

Table 1: General practitioner characteristics according to general practice location (n=128 GPs)

Table 2: General practitioner yearly number of consultations, and consultation length, number of health maintenance/prevention situations and number of chronic conditions according to general practice location in multivariable analyses (n=128 GPs and n=20 613 consultations)

Table 3: Patient and consultation characteristics according to general practice location (n=20 613 consultations)

Table 4: Top 10 health problem assessments according to general practice location (n=45 582)

Table 5: Distribution of health problem assessments by body systems according to general practice location (n=45 582)

Table 6: Top 15 processes of care according to general practice location (n=98 846)

Table 7: Top 10 reasons for encounter according to general practice location (n=54 690)

Discussion

GP sex, age, type of fee agreement, and type of practice did not differ according to their practice location. Those practising in rural areas tended to provide a higher number of shorter consultations and perform more home visits. Patients in rural areas were older and benefited less often from fee exemption for low income. GPs more frequently managed chronic conditions in rural areas and urban clusters than in urban areas. Health maintenance/prevention and no disease situations were less frequent, whereas hypertension and type 2 diabetes were more frequent, in rural areas than in urban clusters and areas. However, the frequency of depressive disorders did not vary according to GP practice location. Cardiovascular and musculoskeletal problems were more frequent in rural areas than in urban clusters and areas. In rural areas, GPs more frequently performed complete clinical examinations and less frequently partial examinations, and prescribed drugs more often. The influence of a GP’s rural practice location on the consultation length, the number of chronic conditions per consultation, and the number of health maintenance/prevention situations was confirmed after controlling for the characteristics of GPs and consultations.

In the present study, rural GPs did not differ from urban GPs according to their characteristics (age and sex) and the characteristics of their practice (fixed fees agreement and type of practice). In contrast, rural GPs in the USA were more often men than urban GPs and worked mostly in solo practice21. French GPs practising in rural areas tended to have a higher workload, comprising nearly an extra 1000 consultations per year (ie 17.5% higher), than GPs in urban areas. Such a trend was also found in a previous declarative French study22. The length of consultation was shorter by roughly 3 minutes (ie 15.5% lower) in rural areas than in urban ones, which is consistent with data from European countries and the USA, and can be explained by a higher workload in rural areas17,23. As observed previously in the USA24 and in Germany25, French rural GPs also provided more home visits than urban GPs, probably because rural patients tend to be older and have a higher number of chronic conditions25,26.

Indeed, the management of chronic conditions was more frequent (by 11.7%) in rural areas than in urban areas, especially for hypertension and diabetes, as was also observed in the USA14 and in Australia27. In addition to the age effect, this trend could be favoured by a higher frequency of smoking, obesity, and poor physical activity of people living in rural areas13,28. Consequently, cardiometabolic complications and mortality are higher in rural areas29,30. Musculoskeletal problems were also more frequent in rural than in urban areas, as has also been reported for the USA17,24. This could be related to the older age of rural patients, in particular regarding osteoarthrosis. The finding of a similar frequency of depression in rural and urban areas is consistent with the results of a systematic review, apart from in the USA where the rate of depression was higher in rural areas31.

In the present study, GPs practising in rural areas delivered 31.7% fewer preventive services. Rural GPs have reported that they usually do less prevention, such as immunisation, screening32, or prevention of diabetes complications33. This finding is not consistent with results from a previous study, which showed more cardiovascular prevention and vaccination being carried out in rural French general practice34. However, the data in that study were collected in 2003, before a gatekeeping system was implemented in France; this reform decreased visits to specialists and to multiple GPs35, which may have favoured the delivery of prevention services by the gatekeeper GPs, especially in urban areas. The lack of prevention observed in rural areas can be due to rural GPs’ higher workload, the greater distance from an inhabitant’s home to a GP’s office, and a lower consultation rate on behalf of rural inhabitants than of urban ones36. It may also be influenced by a higher frequency of walk-in consultations for acute health problems in rural areas, although this is not documented37. Such differences in preventive care access may affect the population’s life expectancy, which is now lower in rural areas than in urban areas in the USA38. Regarding cancer, for instance, people who live remotely from cities have more advanced disease at diagnosis and poorer chances of survival39. Among processes of care, rural GPs prescribed more drugs than urban GPs did. This may result from the higher frequency of chronic diseases in rural areas27. GPs also provided more general medical examinations in rural areas but more partial medical examinations in urban areas. Conversely, in the USA, GPs more often perform general medical examinations in urban areas than in rural areas17,40. Of note, however, the definition of a general versus partial examination probably varies across studies.

Limitations

GP practice location was used as a proxy for the patient’s living place, which can generate some bias for patients who live far from their GP’s practice. All participating GPs were university trainers, who have been recognised globally as representative in terms of sociodemographics and patients. However, they perform better than non-trainers in some preventive care, which should not have substantially affected these findings41. Data on the severity and emergency levels of health problems managed by GPs, which may differ between rural and urban areas and influence GPs’ view of their practice, could not be recorded42,43. Since the study data were collected in 2012 and the accessibility of GPs has tended to decrease since then12, it is likely that the findings would be confirmed and possibly surpassed almost a decade later.

Implications

The high workload and lack of preventive services observed in French general practice is probably related to a shortage of GPs in rural areas5. This constitutes a public health issue because the supply of primary care physicians is associated with a population’s life expectancy44. Since the labour market for health professionals relates to the country’s education and healthcare system45, an integrated approach is increasingly required to adapt the healthcare workforce to the population’s health needs46 and to address imbalanced health coverage47. Strategies to reduce physician shortages in rural regions should also target their determinants, ie the international environment, the rural environment, the work environment, and the individual48. Several interventions targeting the work environment, including the training and the working conditions of GPs, have been carried out in France. Rural trainers may help to reduce the shortage in rural general practice, as medical students who have experienced rural training are more likely to become rural GPs49. This strategy may already be underway in France because GP trainers tend to be over-represented in rural areas41. Collaborative practice and interprofessional training could also reduce or compensate for the lack of GPs and improve the provision of preventive services and the management of chronic conditions50,51. Improvements in the provision of healthcare services expected from these strategies should be monitored11.

Conclusion

French rural GPs tend to have a higher workload with more consultations per year and shorter consultations than urban GPs. Rural patients have more chronic conditions to be managed and are offered fewer preventive services during their consultation. It is necessary to increase the GP workforce and develop cooperation with allied health professionals in rural areas.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the ECOGEN study group, including the Steering Committee, the 54 residents and the 128 GP trainers. They thank Véréna Landel and Philip Robinson from the Hospices Civils de Lyon for help in manuscript preparation. The ECOGEN study was supported by the French National College of teachers in general practice through a grant from Pfizer laboratories.