Introduction

Indigenous peoples are a distinct cultural group that live within, or are attached to, geographically distinct ancestral dwellings1. Globally, Indigenous peoples share issues related to colonization including dispossession from traditional lands and the fragmentation of Indigenous social, cultural, economic and political institutions2-4. High morbidity and low life expectancy occur because of poverty and malnutrition, mental health issues, and a high prevalence of chronic and infectious diseases2. Indigenous children and youth also experience a disproportionate burden of poor health (eg obesity and diabetes)3,4. Articles 21 and 22 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples call for particular attention to be paid to the needs of Indigenous children and youth5.

In Canada, First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples are the fastest growing segment of the population6. One approach to reduce health disparities among Indigenous youth is the implementation of decolonizing strengths-based initiatives7. Children spend a significant amount of their day in school settings, therefore comprehensive school-based health (CSH) promotion approaches are ideal to support positive health behaviors and improvements in educational outcomes8-10. In addition, CSH encourages children to become change agents who promote health behaviors outside of the school environment and in their home environments11-13. CSH approaches for Indigenous children should be culturally relevant, sustainable and promote community autonomy14.

Peer mentorship in Indigenous CSH settings in Canada has been shown to promote positive lifestyle behaviors among younger students including increased fruit and vegetable consumption, increased physical activity and reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and non-nutritious foods15,16. Those who act as peer mentors show improved social skills, self-esteem, sense of empowerment and social responsibility16,17. Given the promising health promotion potential of peer mentorship, more information about peer-led programs for Indigenous youth is required18.

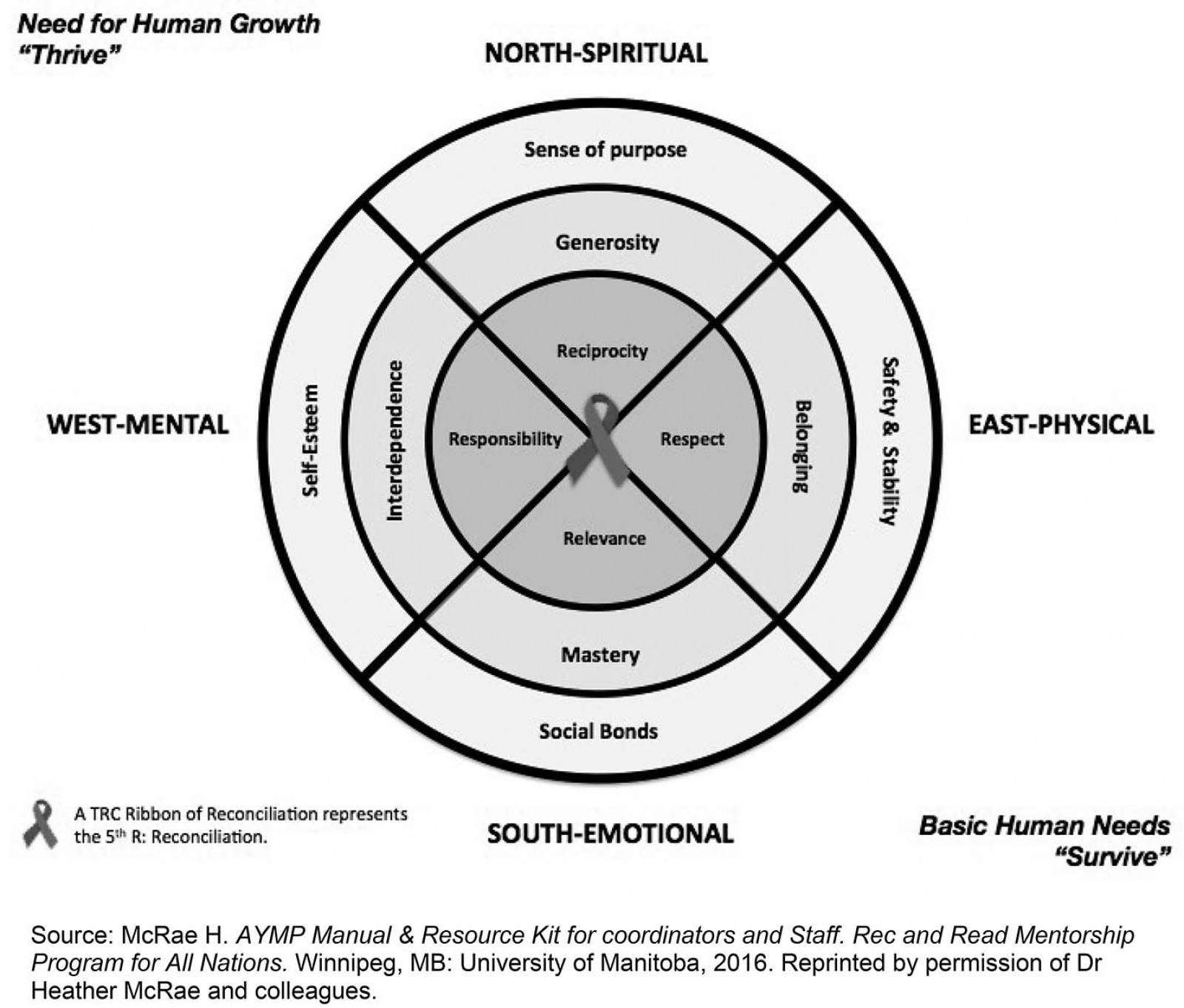

The Indigenous Youth Mentorship Program (IYMP) is a peer-mentorship health promotion initiative in Canada that aims to reduce risk factors for obesity and diabetes, and improve the overall health and wellbeing of Indigenous children and youth. Its core program components are physical activities/games, healthy snacks, relationship building and traditional Indigenous teachings (ie historical cultural values of wellbeing passed down by Elders). It is delivered as a community–university partnership19. The theoretical framework guiding IYMP (Fig1) is based on the pedagogical teachings of two Indigenous scholars: Martin Brokenleg’s Circle of Courage, focusing on the four universal needs of children and youth required to foster resilience (belonging, mastery, independence and generosity)20; and Verna Kirkness’ Four R’s of Learning (respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility)21,22.

The pilot phase of IYMP occurred from 2010 to 2012 in the province of Manitoba. It was found to be effective for mitigating increases in children’s weight gain and waist circumference, and improving healthy living knowledge and self-efficacy23. The Public Health Agency of Canada included IYMP in its list of Best Practices – that is, evidence-based interventions that promote healthy living24,25. Subsequently, IYMP was rippled (IYMP team’s preferred term for ‘scaled up’) nationwide to 13 communities across Canada to determine if it remained effective across multiple settings26.

The purpose of this research was to describe the implementation of IYMP during its first year of rippling to two First Nations community schools in the province of Alberta. Both rural schools delivered the same program with local tailoring of the cultural teachings component. In year 1 of implementation in these communities, IYMP was offered once per week for 20 weeks as a 90-minute after-school program. Youth mentors provided mentorship and offered younger elementary students healthy snacks, physical activity games, and relationship-building activities that included traditional Indigenous teachings under the guidance of a community-appointed young adult health leader (YAHL) (education assistant). The findings of this implementation science research will contribute to understanding the characteristics of implementing a CSH intervention in Indigenous communities. This information can be used to develop feasible health promotion programs for Indigenous children and youth, in Canada and worldwide.

Figure 1: Theoretical framework guiding the Indigenous Youth Mentorship Program.

Figure 1: Theoretical framework guiding the Indigenous Youth Mentorship Program.

Methods

This descriptive case study27 described the implementation of IYMP as an after-school program in two rural schools in Alberta from January 2017 to June 2017. Case studies are useful when studying a phenomenon in a particular setting to illustrate how things occur in practice28. The case is viewed as an object or a ‘bounded system’ and, therefore, a case study was appropriate to study the implementation of IYMP27,29. Descriptive case studies gather data from several sources to provide a rich description of the phenomenon under study27,29.

Setting

The two band-operated schools implementing IYMP are located in small rural First Nation communities in Treaty 6 Territory. They are approximately 1 hour apart by car and 60 km from the closest urban city. Cree, Stoney and English languages are spoken. Each school has a gymnasium, kitchen and outdoor school grounds.

Indigenous Youth Mentorship Program participants

IYMP participants included community-appointed YAHLs (education assistants) who oversaw program delivery and supported the Indigenous youth mentors (grades 6–12, ages 12–18 years) in their role. Youth mentors were identified by teachers or YAHLs. Participating elementary school children (known as mentees) were in grades 4 or 5. In August 2016, an IYMP National Team gathering occurred in Winnipeg, Manitoba, for YAHLs, youth mentors, community leaders, Elders/Knowledge Keepers, research trainees and researchers. At this gathering, each school received an IYMP program manual related to the core components of IYMP, with the understanding that communities would tailor traditional Indigenous teachings in ways that honored the unique cultural context of their own communities.

Data generation

The primary researcher (SL) was a non-Indigenous PhD candidate who formed a relationship with one of the school communities in 2015 and became involved in the IYMP implementation planning process in 2016. SL attended the 2016 national IYMP gathering where she met the IYMP National Team. Subsequently, SL participated in local, regional and national gatherings and teleconferences.

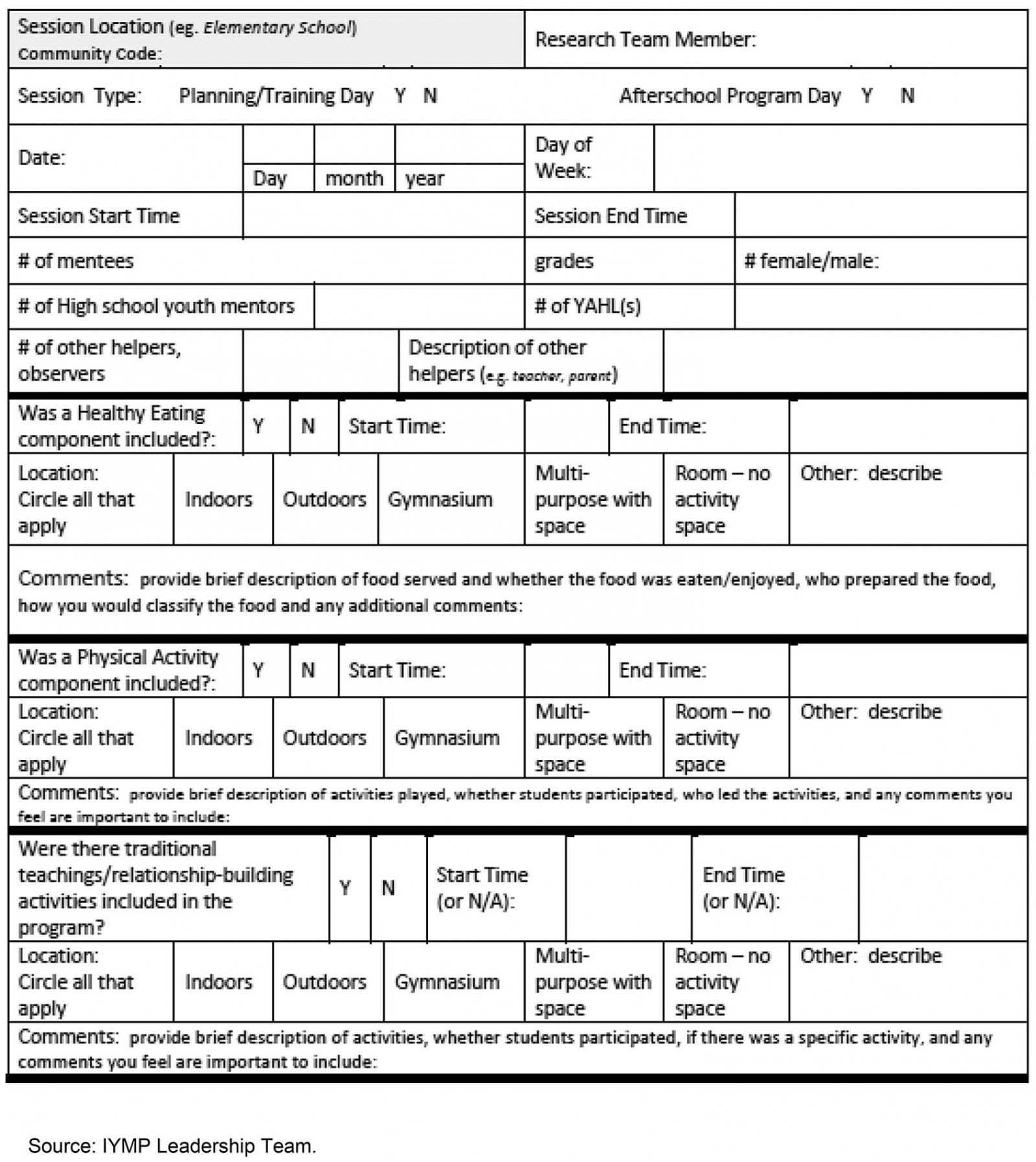

The data generation strategies used in the case study included SL’s onsite participant observations (n=11) of IYMP sessions in the two schools between February 2017 and June 2017. Observations generally lasted 2 hours and included session set-up and clean-up. Notes were recorded on an IYMP program log form (Fig2). The form included information on participants, program activities, content and duration (minutes) of program components, and contextual factors (eg participants’ engagement with each other).

Observations were made about the healthfulness of food served to children using the Alberta Nutrition Guidelines for Children and Youth30. Foods were categorized as choose most often, choose sometimes or choose least often based on nutrient content and how foods align with Canada’s food guide. Choose most often foods are high in nutrients and low in sugar, sodium and fat (eg fruits, vegetables, whole grains and water). Choose sometimes foods contain moderate nutrients and have moderate amounts of sugar, sodium and fat (eg dried fruit with added sugar, sweetened yoghurt). Choose least often foods have low nutritional value and are high in sugars, sodium and fats (eg cookies and donuts).

IYMP physical activities focused on moderate to vigorous intensity activities based on the Canadian 24-hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth31. Children or youth who engage in these intensity levels daily do better in school, feel happier, maintain healthy body weights and improve their self-confidence22,31. Intensity categories of physical activities in IYMP sessions were ranked as ‘sedentary’, where participants were standing in place, lying down or sitting; ‘walking’ where individuals were walking at a casual pace; or ‘vigorous’, where participants were running, jogging or doing cartwheels where they became visibly sweaty (face/clothing) and had rosy cheeks22.

Traditional cultural activities and teachings were embedded within the program. They included traditional teachings (eg Medicine Wheel or Seven Grandfather Teachings), language (Stoney or Cree) and ceremony (eg prayer or smudging).

Program facilitation styles were recorded as frequencies based on the Teacher Monitoring Analysis System and included leading – leader takes control and sets up game; encouraging – leader gives verbal encouragement to participate; facilitating – leader puts out equipment; modeling – leader participates; and unstructured – leader supervises but doesn’t facilitate32.

Log data were entered into a spreadsheet, analyzed and reported using descriptive statistics: number, mean, median and range for interval data. Frequencies were reported for ordinal and categorical data. Quantitative findings were triangulated with observations and field notes to enhance rigour and to provide context for the quantitative findings. Due to the small number of participants, data from both schools were aggregated to strengthen findings and to maintain participant anonymity.

Figure 2: Indigenous Youth Mentorship Program implementation log form.

Figure 2: Indigenous Youth Mentorship Program implementation log form.

Ethics approval

This research adhered to Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP™) principles, enabling each school participating in IYMP implementation to make decisions regarding why, how and by whom data were collected, used or shared33. Community members formed advisory groups that approved research protocols and measures. Informed written consent was obtained from YAHLs. Elementary school children and youth mentors obtained written parental consent and provided their assent to participate. Community consent was in the form of a Band Council Resolution. This study was approved by the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board 1 (Pro00069533).

Results

A total of 33 children, 19 youth mentors (high school) and 6 junior mentors (junior high school) from the two schools participated in IYMP. Five participants (2 children; 3 youth mentors) withdrew from the program because their families moved out of the school jurisdiction. On average, there were 11.7 children (median=11, range=6–24) per program session, 3.3 males (median= 3, range=1–6) and 8.5 females (median=7, range=5–18). One YAHL and 4.6 youth mentors (median=3, range=0–13) were present per session, along with other facilitators (mean 1.2, median=1, range=0–3) such as research coordinators, teachers, parents or Elders. Based on SL’s field notes, there were fewer male than female youth mentors present during program sessions. Weekly IYMP sessions had a mean duration of 87 minutes (median=90, range=75–110). For all sessions, facilitation styles were always combinations of leading, encouraging, facilitating and modeling. No sessions included unstructured supervision.

The nutrition component delivered at each session had a mean duration of 16.8 minutes (median=15, range=10–25), with youth mentors leading the session 41% of the time and YAHLs 59% of the time. YAHLs, youth mentors and sometimes children would help to prepare and/or put out the snacks. Food was most often served in the gymnasium, where socializing would take place amongst all participants and laughter was often observed. The foods most often included were whole, unprocessed foods such as pineapple, carrot, cantaloupe, grapes and bananas. Packaged snacks were included such as crackers and cheese, fruit sauce and fruit cups. All children were observed eating at each session and many said they enjoyed the food. No food wastage was observed. The majority of food was into the choose most often (68%) or choose sometimes (23%) category; however, 9% were in the choose least often category foods such as fruit gum candies. Water was served at every session, with the occasional addition of juice.

Physical activities had an average duration of 70.7 minutes per session (median=70, range=45–95). Youth mentors led sessions 45% of the time and YAHLs 55% of the time. Activity sessions occurred in the gymnasium 73% of the time or in both the gymnasium and outside 27% of the time, depending on environmental conditions. The intensity categories of physical activity sessions were ‘sedentary’ (9%), ‘walking’ (32%) or ‘vigorous’ (59%). Common games were basketball, handball, kickball, parachute and free play. SL observed that male children were more likely to engage in play with male youth mentors or facilitators. Sometimes during play, a child would move to the sidelines to take a break for a few minutes or because they didn’t want to play a particular game. Because relationship building was woven within the program, within minutes another child or youth mentor would encourage the child to rejoin the activities. When a child did not physically participate in an activity they would still participate by maintaining a score card. Children often displayed friendship towards one another by cheering for others during games, patting each other on the back, and joking or laughing together during program sessions.

The cultural/traditional teachings component was embedded within the program. Both schools included Elders from the local community as cultural advisors and teachers. In IYMP the Elders and YAHLs engaged children in activities such as making bracelets using Medicine Wheel colors, sharing circles, the Seven Grandfather Teachings (ie wisdom, love, respect, bravery, honesty, humility and truth), traditional language (Cree and/or Stoney) in games or in prayer, and burning sweetgrass for ceremonial purposes (ie smudging). The Medicine Wheel symbolizes concepts such as the power/medicine of the four directions (east, south, west, north). Many participants helped each other when making the Medicine Wheel bracelets. Traditional teachings were frequently shared when children were gathered in a sharing circle. Questions were asked to set up the teachings such as, ‘What does honesty mean to you?’ Sharing circles were used to debrief at the end of sessions, where children were asked what they liked best that day or to make suggestions for the next session.

Discussion

There is limited information about the implementation and scalability of school health programs developed for Indigenous children globally18,34. To allow flexibility, IYMP schools are encouraged to adapt the mode of delivery and core components to ensure that the program meets their needs26,35. This research demonstrated that it was feasible for two Alberta rural community schools to deliver all program components. Connecting children with cultural traditions and language revitalization are important initiatives in Indigenous communities that promote wellness and strengthen children’s and youth’s resilience36-41. Both schools made cultural infusions to the program through community engagement with Elders and incorporation of Cree or Stoney First Nations languages in games such as ‘tag’. Youth mentors involved in a similar Indigenous peer mentorship program in Canada deemed cultural connections with Elder guidance a key outcome of their mentorship experience40,41.

The majority of snacks offered to children were healthy; however, not all snack choices were in the choose most often category. Although both communities are within an hour’s drive to a city, not everyone has easy access to healthy fresh foods. In consideration of this, IYMP planning in rural and remote locations could work with schools to make fruits and vegetables accessible. Participating communities could also be supported to find ways to encourage the inclusion of more vigorous activities. The Alberta communities had fewer male children, youth mentors and YAHLs. Research is required to see if this gender disparity exists in other communities and, if it does, to explore why there is lower male involvement.

Effectiveness and sustainability in real-world settings is an important component of scaling up programs35,42. In both Alberta First Nations schools, infusing traditional cultural practices into program components was a facilitator for fidelity of program implementation. Optimal IYMP implementation mitigates the risk of acquiring lifestyle diseases because it incorporates holistic approaches that honor local Indigenous voices and worldviews43.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrated that it is possible to implement all core components of a program with flexibility in Indigenous communities by respecting local traditions and knowledge. The lessons gleaned from this research may also be used to understand the rippling of similar Indigenous peer-led mentoring initiatives globally.

Acknowledgements

IYMP National Team members are Roy Arcand, Colin Baillie, Tamara Beardy, Tara-Lee Beardy, Barbara Carlson, Lawrence Enosse, Keri Esau, Leah Ferguson, Rick Fewchuk, Joannie M. Halas, Donna Ivimey, Jay Johnson, Jody Kootenay, Lucie Lévesque, Sabrina Lopresti, Alex M. McComber, Jonathan M. McGavock, Tara-Leigh McHugh, Connie McIvor, Heather McRae, Addy Poulette, Jack Robinson, Carol Rogers, Rene Roulette, Frances Sobierajski, Jenna Stacey, Kate E. Storey, Brian Torrance, Maria Fernanda Torres Ruiz, Mary-Jo Wabano, Noreen D. Willows, Eric Wood, Larry Wood, Nancy L. Young.

References

You might also be interested in:

2017 - Gene therapy renews hope to lower the global rural sickle cell disease burden