Introduction

Chronic disease is currently responsible for sixty percent of the disease burden globally. This is expected to rise to eighty percent by the year 2020 and as the population ages1. It is therefore one of the greatest challenges facing healthcare systems throughout the world. Chronic disease is being labeled as that of lower socioeconomic groups and has reached epidemic proportions in Indigenous communities in the past decade1. This is particularly true for renal disease, with renal failure doubling every three to four years in some remote Australian states2, while remaining the same in more urban southern states3. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander diabetes rates are also the highest in the world on some indicators4. However, while we have found that mortality levels have been dropping within most Indigenous populations in other first world countries in the past 20 years, Australia remains the striking exception5.

In 1999 and 2001, the Northern Territory (NT) and Queensland (Qld), who have the second and third highest Australian Indigenous populations, developed chronic disease strategies6,7. The two strategies had a common three-point framework of prevention, early detection and best practice management based on the available evidence, however they differed in some of the diseases they prioritised.

Recent evidence now tells us that the use of a systematic population focused approach will have a greater effect on the patient's health outcomes, than individual care, and will be far more financially efficient in the long run1,8,9. Therefore, in 2003 the Australian Government, through its Public Health Education and Research Program (PHERP), funded an innovative program to increase the workforce capacity across northern Australia. It involved seven partners - three universities, two health departments and two Indigenous organisations - Menzies School of Health Research, James Cook University, University of Queensland, Queensland Health, the Northern Territory Department of Health and Community Services, Apunipima Cape York Health Council and Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance of the Northern Territory.

The ultimate aim of the project was to reduce the impact of preventable chronic disease among high-risk populations in northern Australia, through improving the capacity of rural, remote and Indigenous health workforce and services10. It targeted all of the remote and rural health workforce - doctors, nurses, Indigenous health workers, allied health professionals and health centre managers - and those who educate them. This article provides a brief overview of the process, insights and results for others to consider as they also struggle with the challenges that chronic disease offers.

Project methodology

A training needs analysis was conducted in early 2004. A triangulated approach was used that included 76 semi-structured interviews with key informants, 35 surveys of remote staff across NT and north Qld, and literature and resources searching to support the work. There were a total of 111 participants. They included: NT and Qld Health staff, community controlled health organisations, policy makers, non-government education providers, clinicians, and remote health staff - nurses, doctors, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, health centre managers and allied health professionals - which gave the project great breadth. The interviews and survey differed slightly but elicited information regarding their: perceptions about early detection, prevention and chronic disease management; workforce training and support needs; access to information technology, resources, and preferred training methods.

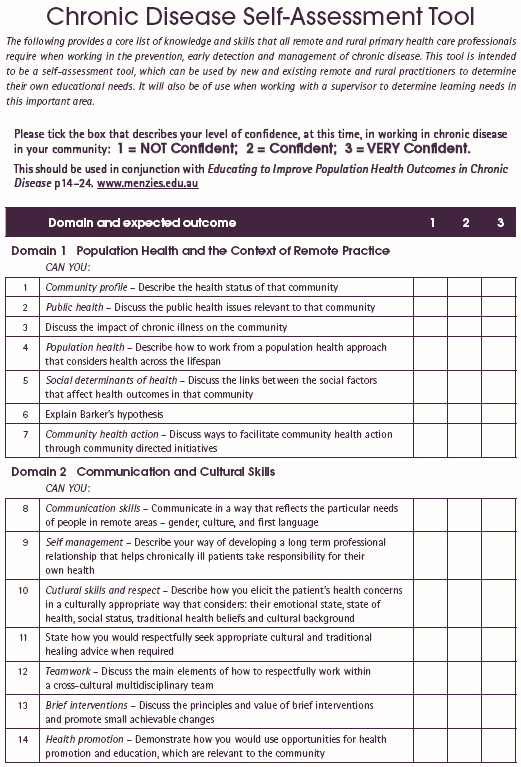

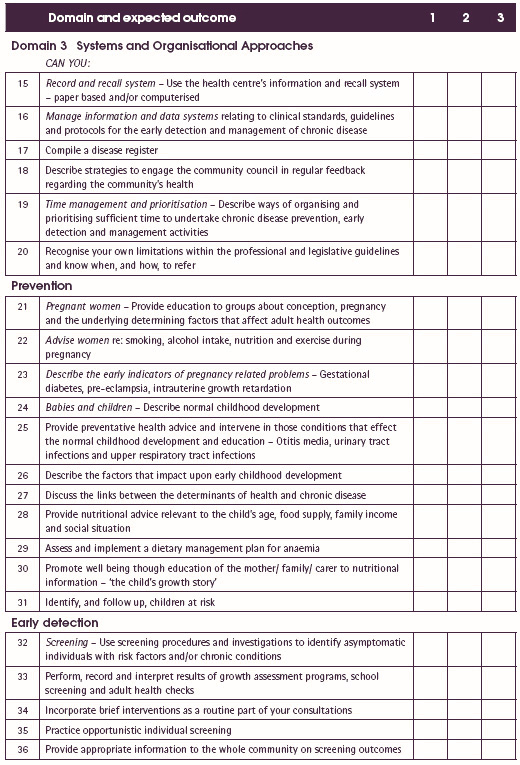

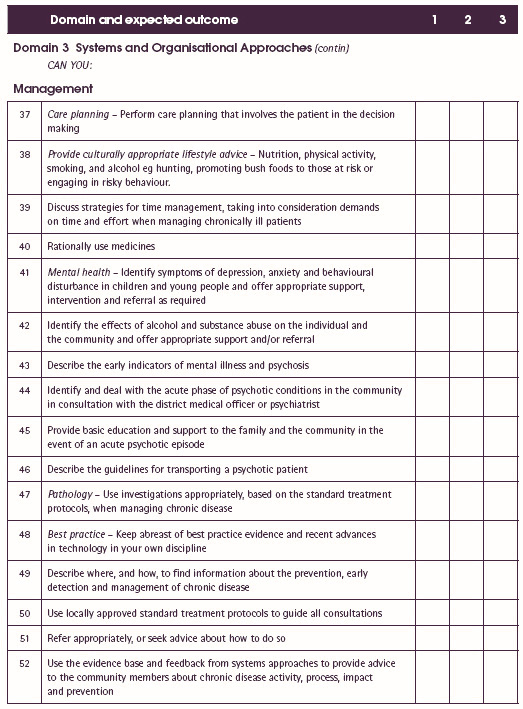

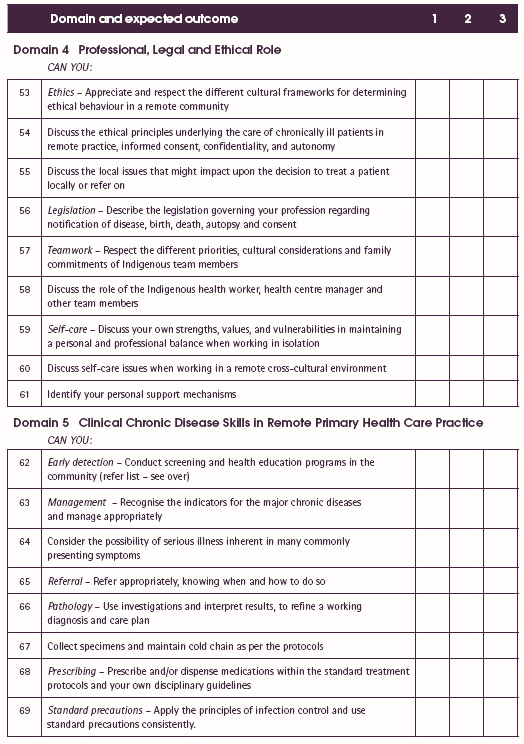

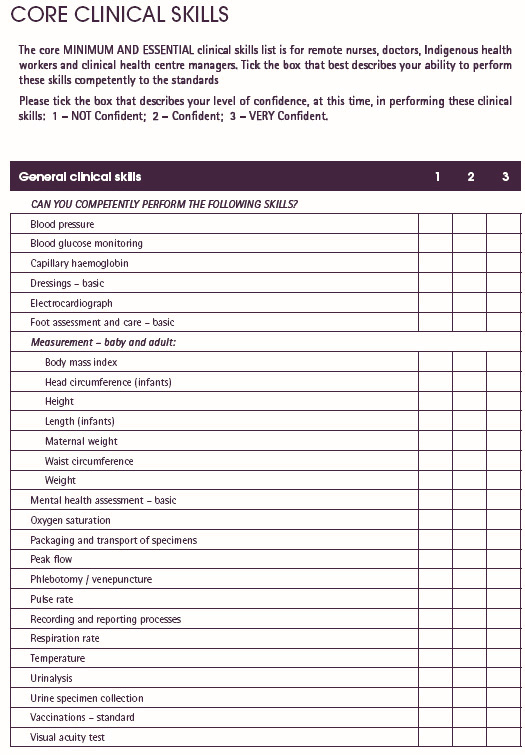

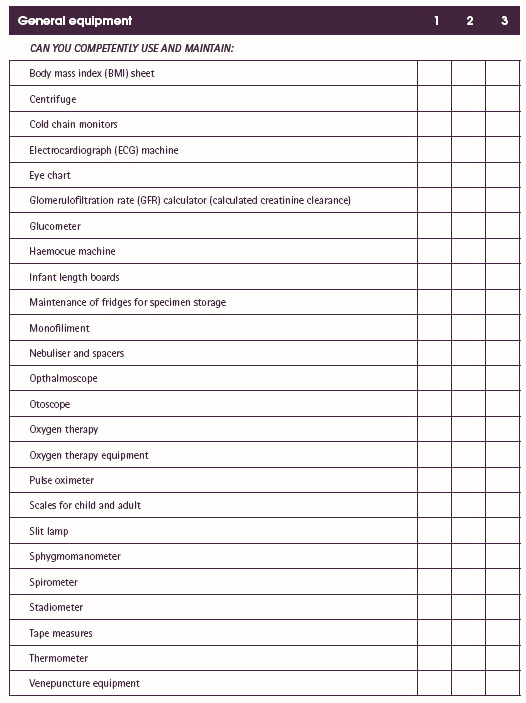

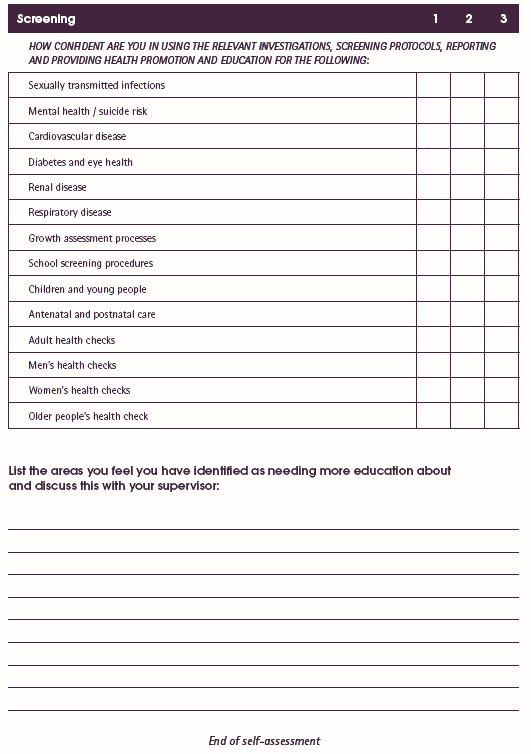

The results of the training needs analysis and the existing competencies and standards of the various professions provided a platform for identifying the priorities for the development of the curriculum framework. A workshop of 35 educators was conducted in August 2004, which assisted in validating the draft curriculum framework, identifying the content and in re-orientating the educators to the chronic care and population health model. The core content provided the development of a self-assessment tool, which was piloted in 2005 (Appendix I). During 2005 and 2006 several universities and two health departments were assisted in a process to embed and integrate the framework into their existing and new programs. This provided an avenue to link and apply research to policy and practical implementation at the grassroots.

Project outcomes

Needs analysis

The consultation phase identified numerous challenges for those educating and preparing the rural and remote health workforce in the prevention, early detection and management of chronic disease. The main findings were that there was very little difference in the training needs identified between the disciplines - medicine, nursing, Indigenous health workers and allied health - and few practised in a population-based approach. There was a very strong focus on the management of chronic disease as opposed to the prevention and early detection, which were seen as the 'hard end'. While most people had heard of the chronic disease strategy, few could explain how they were implementing it in their communities. The main barrier to successful implementation was the demands of acute care over chronic disease management, which always prevailed. The staff perceived that they were poor in the prevention and early detection of chronic disease, but fairly good in the management of chronic disease.

The practitioners preferred learning though workshops in their own communities, accredited and disciplinary specific training and had poor access to the internet in remote communities, particularly in the NT. The self-assessment tool was piloted with remote staff during 2005 and was found to be particularly useful for pre- and post-training purposes and as a discussion starter for all disciplines and groups. Disciplinary groups have since adapted it to meet their own particular needs.

There were some significant staffing increases in the NT to deal with chronic disease, though a distinct drop was reported in Aboriginal health worker numbers. The orientation, education and preparation programs were found to be inconsistent and unsustainable due to the extremely high turnover rates of staff, amid a worsening health status. There was a distinct lack of sustainability built into most approaches, and acute care always predominated.

The initial training needs analysis identified the top 10 areas where the workforce, and those who train and manage them, thought were areas of training need, as seen in Figure 111. The top four areas were prevention focused training, using a systematic and population health approach and working in a respectful way as part of a cross-cultural team.

Figure 1: Identified training needs (n=100).

Change in project direction

The original intent of this project was to develop a curriculum and training resources to support the workforce. However the consultation phase found that the issues were so broad, and common across the disciplines, that one or two additional resources would provide little change to assist the required paradigm shift. Therefore it was determined by the steering committee that this initial approach would not have the desired, and required, impact upon the workforce due to the high turnover rate of staff, the breadth of the work, and the integration of chronic disease into all areas. Therefore five principles to manage and progress the project were endorsed by the steering committee in May 2004:

- Prioritise the populations suffering the greatest burden of chronic disease - remote Indigenous communities

- Target those who prepare and educate the health workforce, as this will have the greatest impact - health educators across all disciplines

- Develop a curriculum framework that:

- is population and outcomes based

- focuses on those factors that affect health - the social determinants of health

- integrates prevention, early detection and management into those things that everyone practices. This resulted in the development of the domains of remote practice.

- is population and outcomes based

- Develop an implementation strategy that could be integrated into all workforce training - undergraduate, postgraduate, and professional development across the disciplines

- Develop any resources and a web-based annotated bibliography to support the educators and the workers in a sustainable way.

Curriculum development and implementation

The curriculum framework (Fig 2), was developed using four main foundations. It is:

- Population health based It starts with pregnant women, babies, young children, youth, men, women and older people - through the health transitions of the lifespan.

- Needs based It is structured to focus on those 'areas of workforce need' and where there are 'identified skills gaps' - prevention and early detection.

- Impact focused It focuses on those things we can 'impact upon' - the social determinants of health; and those things we 'can manage' - chronic diseases identified in the chronic disease strategies.

- Organised using the domains of remote practice The domains are the critical knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary for the prevention, early detection and management of chronic disease. They provide an organising framework for the list of expected core outcomes for all disciplines.

The most used aspect of the curriculum framework are the domains of remote practice, which three universities, two health departments and several non government organisations have used to provide an organising framework for their existing and new programs12. These domains were developed by examining and cross-referencing the curriculum, professional standards, competencies and objectives, found in the disciplines of medicine13-16, nursing17-19, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health worker20,21, public health22 and allied health23; plus those found in various public health masters programs24,25 and other various relevant documents6,7,11,26,27. These domains now provide a flexible basis on which to build professional development and tertiary education programs to prepare the workforce for the impact of chronic disease.

In August 2004, 35 educators representing a cross-section of all health disciplines and industry groups attended a three-day workshop in Darwin. They each presented what existed in their area, swapped models, and undertook training in the chronic care model and using a population health approach. They discussed how they could refocus their orientation, professional development and accredited training programs towards a comprehensive, integrated and population-based process, which would equip health practitioners to deliver the primary healthcare components of the NT and Qld chronic disease strategies. This workshop proved very successful in that it provided strong links among the states and organisations, provided support mechanisms for future development, and educated the educators. Follow-up teleconferences and meetings with group participants assisted in monitoring progress.

A final curriculum framework was published in January 2005 and a second edition was published in February 2006. During 2005 the project consultant worked closely with the various groups in practical ways to integrate, adapt, adopt or implement the chronic disease curriculum framework into their existing and new training programs, using mainly the domains of remote practice to guide the process. This proved to be practical, timely and successful because it provided a solid link between research, policy development and practical implementation at a local level. She also promoted the work at numerous national and state conferences and at an international Indigenous conference in Canada.

Figure 2: Curriculum framework. Source: reference 12, reproduced with permission.

The outcomes of this project have been more significant than was originally anticipated. This project has resulted in a curriculum framework and implementation model that is comprehensive, practical, integrated, outcomes based, and focused on the social determinants of health using a population-based approach to health care. It is useful for all health professions and can be adapted to suit their particular needs. The process has also identified the need to influence educators as a critical step in the whole endeavour if we are to bring about the required change in practice.

Conclusions

There are significant issues that need to be addressed in the way in which the Australian health workforce is educated to practice as the population ages and chronic disease implodes in the 21st century28. This is particularly so for those who work in the 1218 discrete remote Indigenous communities, which house a quarter of the total Australian Indigenous population in Australia29,30. We also assume that the educators automatically understand the required change as they prepare undergraduate and postgraduate students and health staff for practice. However the majority have also been trained in the acute care model and are comfortable in working in this way.

While it is always important to have more research being undertaken in this important area of chronic disease, we also need to be working in practical ways to alter the acute disease based practice model that dominates in the health workforce, towards an integrated, systematic, population-based approach. This project has made some inroads to assisting this process but it will take a shift in thinking from those who guide our undergraduate preparation programs to have it seriously addressed to meet the needs of the population in the 21st century.

The curriculum framework can be accessed via www.menzies.edu.au or email: info@menzies.edu.au to order a free hard copy.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Australian Government Public Health Education and Research Program (PHERP).

References

1. WHO. Innovative care for chronic conditions: Building blocks for action. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

2. Hoy W, Rees M, Kile E, Matthews JD, Wang Z. A new dimension to the Barker hypothesis: Low birthweight and susceptibility to renal disease. Medical Journal of Australia 1999; 56: 1072.

3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Chronic kidney disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra: AIHW, 2005.

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2002. Canberra: AIHW, 2002.

5. Ring IT, Firman D. Reducing Indigenous mortality in Australia: lessons from other countries. Medical Journal of Australia 1998. 169: 528-533.

6. Weeramanthri T, Hendy S, Connors C, Ashbridge D, Rae C, Dunn M et al. The Northern Territory Preventable Chronic Disease Strategy - promoting an integrated and life course approach to chronic disease in Australia. Australian Health Review 2003; 26(3): 31-42.

7. Clearing House for Indigenous Rural and Remote Programs. Business Plan Year 3: Implementation of the enhanced model of primary health care. Cairns, Qld: CHIRRP, Queensland Health, 2004.

8. Wagner E. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness. Effective Clinical Practice 1998; 1: 2-4.

9. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Affairs 2001; 20: 64-78.

10. McDermott R, O'Dea K. Grant Application PHERP Round 2. Cairns, Qld: James Cook University, Menzies School of Health Research, 2001.

11. Smith JD. Progress report for steering committee: Phase 1 - Consultation phase. PHERP Innovations project, public health workforce development in chronic disease prevention, early detection and management in rural, remote and Indigenous communities. Darwin, NT: Menzies School of Health Research, 2004.

12. Smith JD. Educating to improve population health outcomes in chronic disease, 2nd edn. Darwin, NT: Menzies School of Health Research, 2006.

13. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Training Program, RACGP Training Program Curriculum. Melbourne: RACGP, 1999; 1-220.

14. Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine and Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Training Program, Pilot Remote Vocational Training Stream Curriculum Statement. Melbourne: RACGP, 2000.

15. Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine. Primary Curriculum, 2nd edn. Brisbane: Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, 2002.

16. CDAMS. CDAMS Indigenous Health Curriculum Framework. Melbourne: VicHealth Koori Health Research and Community development Unit, University of Melbourne, 2004.

17. Australian Nursing Council. National competency standards for the registered nurse, 3rd edn. Canberra, ACT: ANMC, 2000.

18. CRANA and CRAMS. National remote area nurse competencies. Armidale, NSW: Centre for Research in Aboriginal and Multicultural Studies, University of New England, 2001.

19. ANCI. ANCI National competency standards for registered nurses, 3rd edn. Brisbane, Qld: Queensland Nursing Council, 2000.

20. Community Services and Health Training Australia Ltd. Qualifications framework: Health training package (HLT02) population health, submission to NTQC. Sydney, NSW: CSHTA Ltd, 2004.

21. Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce national strategic framework. Canberra, ACT: Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, 2002.

22. Human Capital Alliance. Calculating demand for an effective public health workforce. Final report for the National Public Health Partnership. Sydney, NSW: Human Capital Alliance, 2004.

23. Glynn R. Continuing education needs of the allied health professionals in Central Australia. Alice Springs, NT: Centre for Remote Health, 2003.

24. Centre for Remote Health. Graduate studies in remote health practice, guide to learning. Alice Springs, NT: Flinders University and Charles Darwin University, 2004.

25. Menzies School of Health Research. Chronic disease epidemiology and control. Unit outline and guide to learning Semester 1. Darwin, NT: Menzies School of Health Research, 2004.

26. Central Australian Department of Health and Community Services. Section 3: Framework for action - implementation guide, in Community health services - remote - PHC atlas. Alice Springs, NT: NT Department of Health and Community Services, 2003.

27. Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association. CARPA Standard Treatment Manual. Alice Springs, NT: CARPA, 2003.

28. WHO. Preparing a health care workforce for the 21st Century. Geneva: WHO, 2005.

29. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Yearbook Australia 2003: Population distribution. Canberra: ABS, 2003.

30. Smith JD. Australia's rural and remote health: A social justice perspective. Melbourne, Vic: Tertiary Press, 2004.

_________________

Appendix I: Chronic diseases self-assessment tool