Introduction

About 50% of the global population lives rurally, yet in countries where rural populations exceed 70%, only 16% of rural residents have access to universal health coverage, resulting in poorer health outcomes1-3. Many stakeholders are recognised to play a part in improving rural health4. Among these are rural health academic researchers, situated in rural areas, who contribute to addressing an evidence base that informs the specific nuance of health with respect to rural places4-7. Developing capabilities for rural health research is viewed as important in many countries but there is only scant evidence about this field, from Canada, mainly limited to the perspective of stakeholders5,8. In light of this, the authors aimed to interview rural health doctoral-trained researchers working in rural and remote sites, to explore the field of rural health research and how it can be fostered.

There are strong examples worldwide of rural-based researchers in Australia, Canada and the USA, developing significant evidence that has informed major rural policy reforms, service models, community action and rural health problems9-14. Further, major rural health strategies consistently identify the need for more rural health research to inform ongoing policy and program priorities13,15-17. At the community level, the availability of rural researchers plays an important role in supporting community self-determination – that is, local problem-solving for local solutions. A rural-based academic workforce contributes to rural job creation, expanding access to high quality education and addressing rural health system improvements, all of which underpin rural aspects of the Sustainable Development Goals18,19. Embedding research within rural health services assists to build a culture of teaching and learning on top of the ‘service’ imperative tied to working in underserviced environments. This is likely to fuel a positive service and professional development environment, critical for attracting and maintaining staff16. Having doctoral-trained researchers based in rural sites is also likely to play a key role in bolstering rural workforce recruitment given that early career doctors seek research opportunities as part of the career development and specialisation process20. However, achieving these things relies on a trained rural health academic workforce based in rural areas, about which we know very little.

Investing in place-based interventions is considered to be a critical part of tailoring strategies to context, building social engagement and fostering local economies21. Building rural health research capacity has its roots in a similar philosophy. Compared with metropolitan research, tailored ‘place-based’ knowledge developed within a social contract with rural communities is also potentially more translatable than ‘place-neutral’ knowledge. Specifically, by attending to rural places as a dimension of the research, it has the potential to address rural-specific levers and interactions such as geography, community structure, health services and workers that impact health in heterogeneous rural places. Further, research that is done by researchers with direct experience of the places under study, the researcher’s lived experience and community networks and connections are likely to assist in the formation of relevant research questions, engaging partners and translating findings. Studies have shown that the uptake of research by end users relies on evidence that is perceived as credible, accessible, relevant, based on good evidence and endorsed by opinion leaders22. Rural health research that is done in cities is likely to lack credibility and endorsement of reputable rural stakeholders and miss the necessary community engagement23. Holding resources away from rural communities also devalues the phenomenon of interest and may miss contextual nuances, instead supporting metropolitan gains and potentially ‘othering’ rural communities in a phenomenon described as geographical narcissism24.

Australia is a unique example of a country that has led internationally through a national strategy investing in rural health academic networks since 1996. Under the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program, the Australian Government has provided recurrent funding for regional and rural university sites to deliver both rural clinical training and rural health research. The rural research expected under these contracts must cover issues of training, rural workforce, models of care, rural health topics and Indigenous health25. Contracts determine that researchers must also offer opportunities for rural staff and students to participate in research. The research produced through this strategy has already been described; however, the nature of the rural researchers involved and their work has not18,26-28. Given this policy is currently under review, more information about how the research aspects of this policy are faring is expected to be helpful29.

Rural health researchers are eligible to apply for a range of competitive research grant funding opportunities or may receive philanthropic funding. In Australia, a recent review of 16 651 projects funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; a key ‘health-related’ funding body in Australia), identified that only 1.1% rural health research projects were funded between 2000 and 2014, highly underrepresented relative to the 29% of Australian people living rurally30,31. Understanding the rural health research field may assist to identify why rural health research is not attracting more of the $800 million annual NHMRC funding dedicated to research. Additional competitive funding is possible via the Australian Research Council (often difficult to fit to rural health as it excludes research of health outcomes) and the Medical Research Future Fund (expected to grow to $20 billion in 2021), which is allocated competitively according to ministerial interests within priority topics, of which rural health is not one (based on the 2018–2021 plan)32.

Defining the field of rural health research may assist to target policy strategies for fostering this field, as well as promoting a sense of belonging and recognition for the academics involved.

Methods

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 rural early career researchers (ECRs) from Australian regional, rural and remote locations. These were defined as <8 years full time equivalent from doctoral degree completion, to maximise inclusion. ECRs were selected as they play a role in ‘doing’ rural research giving them a sense of the realities of this field, they are at the beginning of their careers, a time when they can provide fresh perspectives and anecdotally, they are considered to constitute the bulk of rural research-active academic staff. The ECR period is also identified as requiring specific definition, support and planning for academic workforce development33.

Procedure and semi-structured interviews

Subjects were recruited via the Federation of Rural Academic Medical Educators (FRAME) and the Australian Rural Health Education Network (ARHEN). On the researchers’ behalf, they sent information about the study to the representatives in constituent organisations of 16 university departments of rural health and 20 rural clinical schools, with an enclosed package that they could forward to invite ECRs to participate. Snowballing via email was encouraged to reach other rural researchers external to this network. No reminders were given as the study was well subscribed. Purposive methods sought to select researchers with different characteristics, such as sex, age group, rurality, distance from main university campus and rural origin and career background/experiences34.

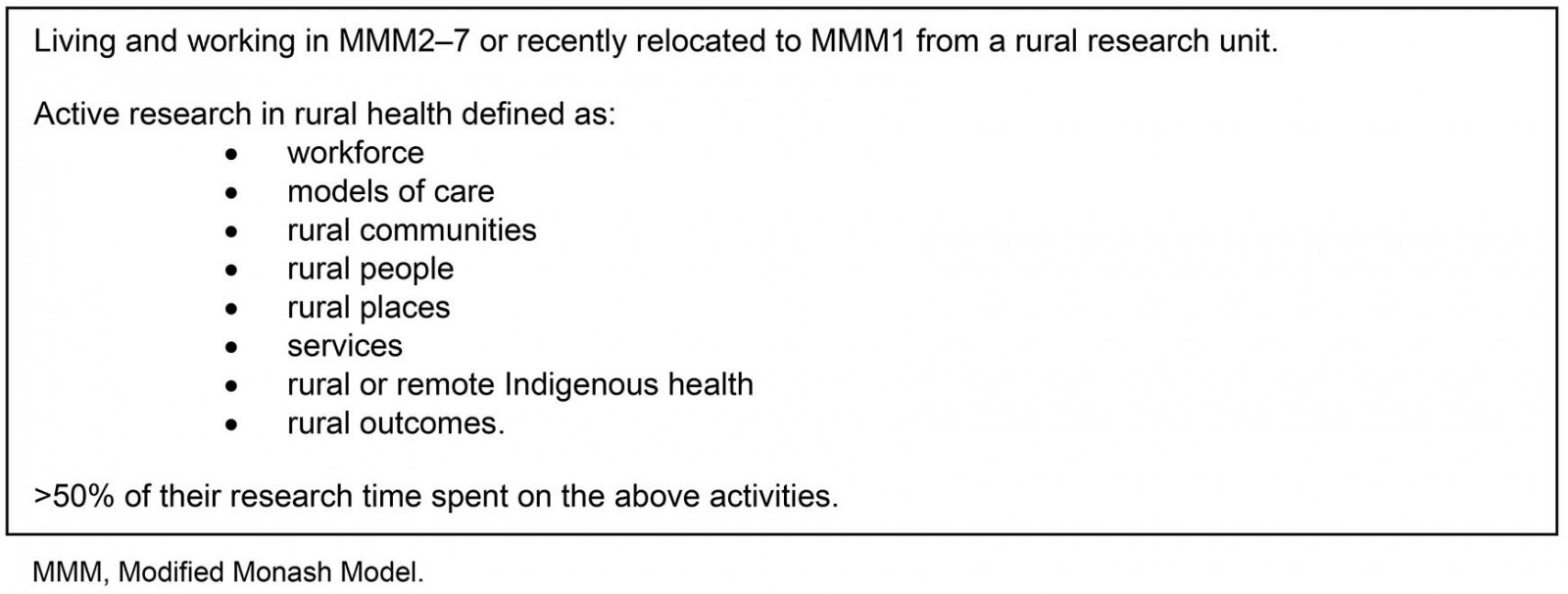

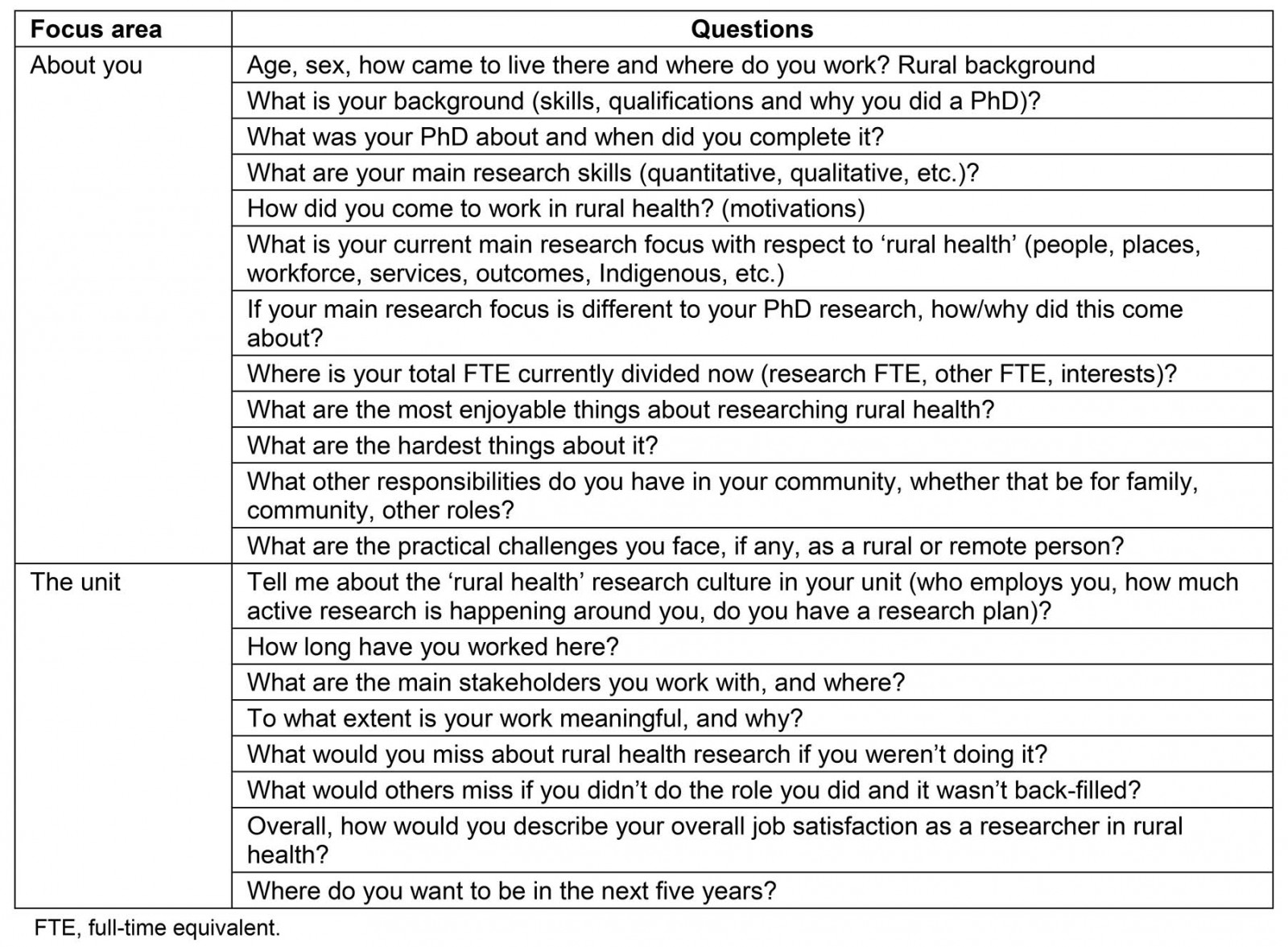

After screening eligibility (Box 1) and completing informed consent, a video-conference interview of 50–70 minutes duration was held between August and December 2019. Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data collection continued until authors agreed to thematic saturation. During the interviews, participants were asked how they became a rural health academic and to describe their professional background, training, work and research experiences in their current role. Interviewees were prompted to elaborate on experiences and expand on emerging themes (Table 1).

Box 1: Study eligibility criteria

Box 1: Study eligibility criteria

Table 1: Study interview schedule

Data analysis

To build understanding of the data, all three authors conducted at least three interviews, took post-interview notes and regularly met to discuss emerging themes. After all of the interviews were completed, transcripts were anonymised using a uniquely identifying number, which was applied to the script. Theoretical and inductive thematic analyses were undertaken. Theoretically informed analysis involved the authors (all rural health ECRs) applying their knowledge of the broader literature about rural health work35-41. Additions and alterations to the coding framework were made as blocks of five transcripts were completed, shared equally between the authors. Authors then double-coded another transcript, identifying reasonable concurrence with existing themes but adding extra codes where these were identified. Inductive coding specifically built on these codes, whereby data elements were considered without any set framework, so that the themes were further developed, strongly related to the data42. This involved in-depth review and analysis, led by the main author. The findings were discussed by the team, checking the data for internal corroboration of disconfirmation, with the team reaching consensus as to the final themes35,43. In the process, the team aimed to promote self-reflexive analysis by considering the influence of their own experiences on the interpretation of data, by extensive written and verbal reflection by team members44,45. To ensure separation of the findings from the authors’ own roles as rural health researchers, thereby minimising bias46, interpretations of the data were tested by regular group discussion, and each team member only interviewed participants not working in the same research unit. The process of analysis involved multi-layering over 6 months, until thick description and triangulation of findings occurred for confirmability47.

To aid interpretation of the data, responses were reported as relating to the number of participants: 1–4 participants as ‘few’, 5–8 as ‘some’, 9–13 as ‘many’ and 14–17 as ‘most’. Further interviews were depicted, using the Modified Monash Model (MMM), according to whether the ECR was based in a regional (MMM2), rural (MMM3–5) or remote (MMM6–7) setting using ‘reg’, ‘rur’ and ‘rem’ subtext respectively for quoted material48. The Modified Monash Model is the Australian Government’s geographical scale that denotes areas that are metropolitan, rural, remote or very remote, based on population size and remoteness.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from Monash University (ref. no. 20595), ratified at the University of Queensland and James Cook University.

Results

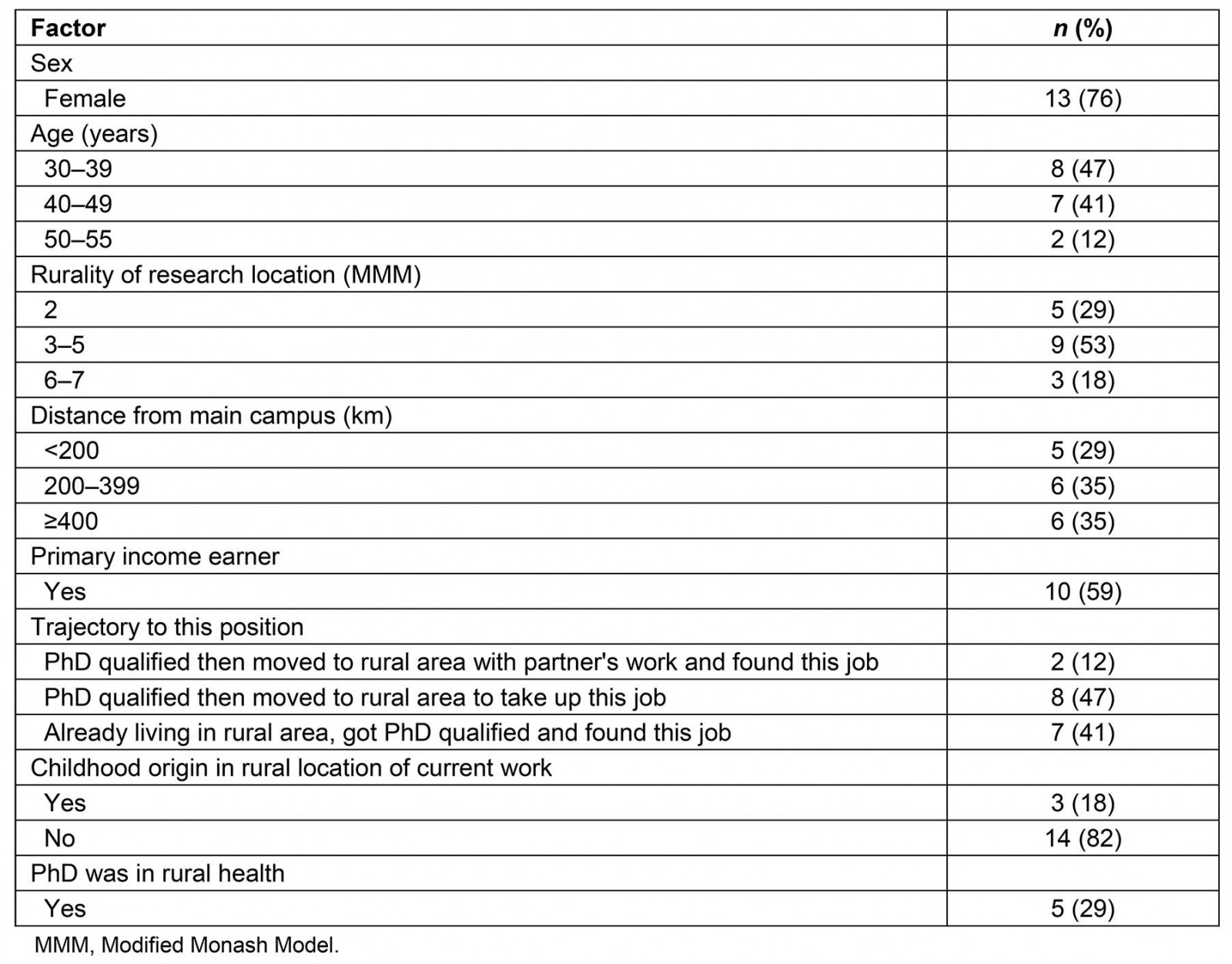

Demographic characteristics of the sample are summarised in Table 2. Respondents included 13 (76%) females, 15 (88%) aged 30–49 years; 10 (59%) were primary income earners. Overall, 5 (29%) were based in regional areas (MMM2), and most (n=9; 53% and n=3; 18%, respectively) were in rural (MMM3–5) or remote (MMM 6–7) locations48; n=12 (70%) were more than 200 km from their main university campus. A third (n=5; 29%) were qualified with a doctoral degree specifically in the field of rural health. Overall 14 (82%) were employed within the FRAME/ARHEN network via the Commonwealth-funded Rural Health Multi-disciplinary Training (RHMT) program and others were employed in NHMRC postdoctoral positions, rural faculties and philanthropic funding. At the time of this research the RHMT program had 15 months of funding remaining, with the potential for renewal pending a government review, which commenced in 2019.

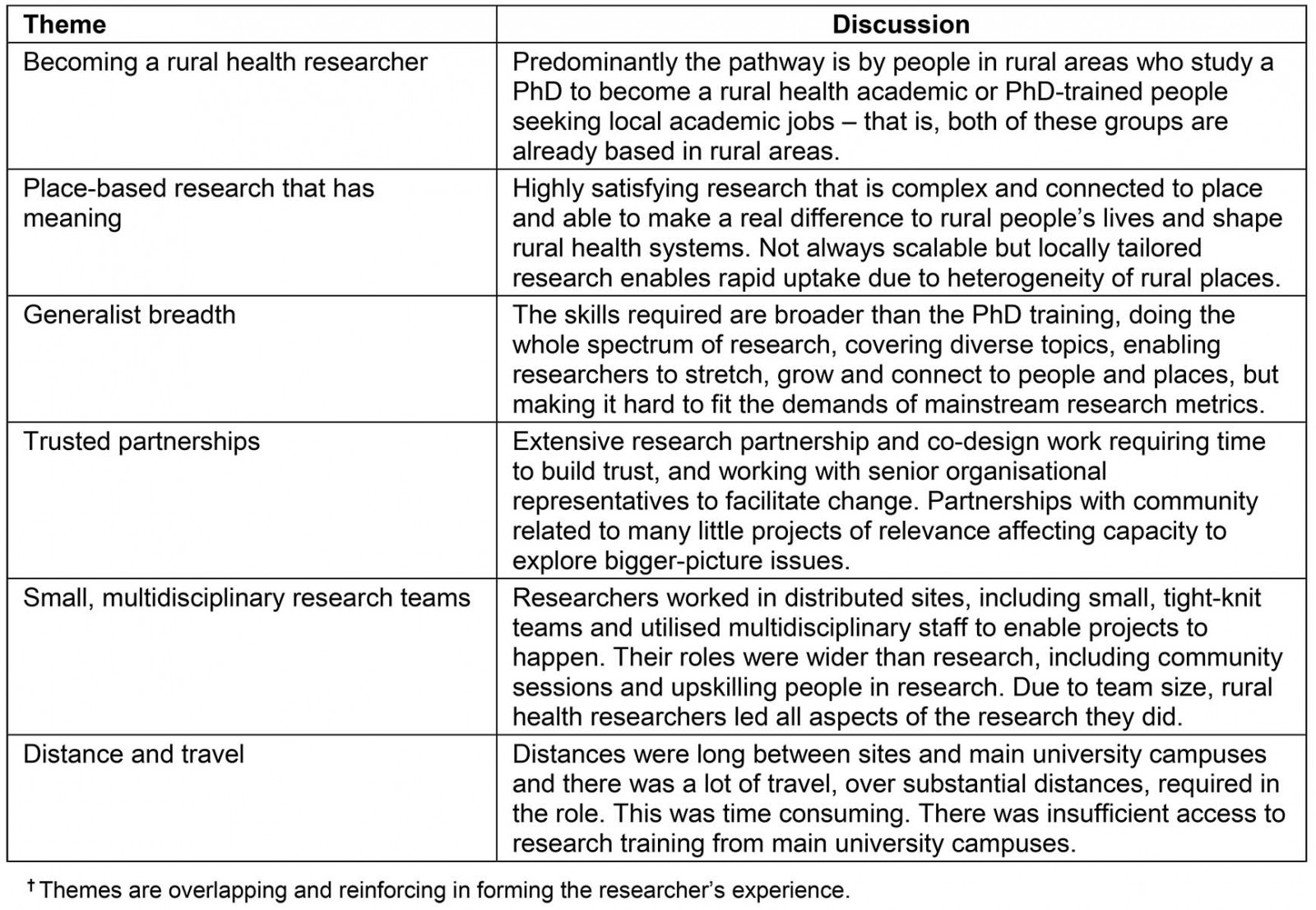

Six key themes were identified: becoming a rural health researcher; place-based research that has meaning; generalist breadth; trusted partnerships; small, multidisciplinary research teams; and distance and travel (Table 3).

Table 2: Characteristics of rural health researcher study participants (n=17)

Table 3: Identified themes related to working in the field of rural health research†

Becoming a rural health researcher

Participants described three trajectories to becoming a rural health researcher: PhD-qualified individuals moving to a rural location with a partner’s work and finding a job as a rural health academic (n=2; 12%); moving rurally for a research job (n=8; 47%); and rurally based people who studied a PhD to get a rural academic role (n=7; 41%). The third group had ≥20 years of experience prior to their research role and some noted a PhD provided an opportunity for a local career development pathway:

We moved to this [regional] location 18 years ago and I worked in my profession for a little while and … there was nothing on the horizon clinically for me ... I needed to get a PhD. So, I set about pursuing that. (Reg_1)

There’s no actual clinician pathway to progress so I guess this [getting a PhD] was just another way to keep ticking along in terms of career sort of thing. (Reg_2)

Eighteen per cent reflected that the rural health research role offered the chance to return to rural areas where they had grown up:

… the job came up at a time that I had reflected on a desire to … get out of the city and get back to the bush, where I was raised. It just happened to be where I was from. (Rem_1)

Place-based research that has meaning

Most reported that rural health research was highly satisfying, being complex, connected to place and spanning diverse and novel academic methods and diverse topics such as workforce, rural service models, health interventions and rural population health issues:

… the research you’re doing [is] connected to place, as a place-based researcher, is extremely complex … the complexity of individual health services, communities …. (Reg_2)

… some of the problems are so complex and you can’t solve the problems using traditional research methods or evaluation … I find it really satisfying actually. (Reg_6)

One of the projects I’m involved in is … the resilience of isolated children and their social and emotional wellbeing. (Rem_1)

Many enjoyed the proximity of their research for addressing social justice issues, affecting real changes in rural health systems, and producing research that contributed to rural advocacy:

… you’re not sitting in an ivory tower, you really get to see why it matters and you get to interact with the people it’s going to make a difference to. (Rem_1)

… If we do our work in a remote area you can directly see its implication happen fairly quickly … you see the direct translation of your work into the benefit of the community’s health or wellbeing. (Rem_3)

I see the inequalities, urban to rural and remote. I see the lack of airplay that we get in terms of the issues and addressing the issues. I just think the work we’re doing is really important. (Reg_1)

Many noted the value of rural ‘place-based’ research for its capacity to address local solutions. But some also perceived a tension concerning producing research that could be scalable, the latter affected by funding and partnerships:

… you need the local stuff because that will address the heterogeneity of that – or like the uniqueness of that local area but there also needs to be then that macro stuff as well, that broader stuff for that bigger picture. (Reg_2)

… we’re doing research quite often that’s relevant to our region. Where it gets a little bit tricky is when you extend out of local and you look at more national or international … often our projects are funded for such a small piece of the pie ... (Rem_1)

Generalist breadth

Many noted that the breadth of skills required in rural health research was wider than their doctoral training. This was specifically observed by those not PhD-trained in rural health. Of these, two were from rural areas where they were working:

I think the biggest challenge is your PhD doesn’t set you up for the real world of [rural health] research … It’s little things like doing a systematic review is not part of my PhD, but I’m now involved in three of them. (Rem_1)

It’s actually mostly qual[itative] which is something else I’ve had to learn. (Rur_2)

Another had a metropolitan origin:

Yeah, my experience is, [so far, to date] is that rural health research is very heavy qualitatively. I hadn’t done any of that before, so I had to be upskilled. Still working on that. (Rur_7)

The need to draw on broad skills within rural research roles and work in connection to community was perceived as satisfying and potentially enabling of career growth over opportunities in urban university settings:

… you are doing the whole spectrum of research … (Rur_5)

I love the travel. I love the connection of people. I think you get to stretch and grow and develop more rapidly in your career and I think that’s a really good enabler out here. Those opportunities that would take years to get in an urban university. (Rem_1)

I think it’s the diversity … you become a generalist. … you have to adapt everything you deliver out here, so I’m very a bio/psycho/social model person where you’re taking the person’s environment and their personal factors ... (Rem_5)

However, the breadth of their research role and research experience was noted by some to be at odds with the performance demands of mainstream academic careers:

… the biggest challenge is that really firstly you’re pulled in every direction and I see, you know the research that I’m doing at the moment is around generalist type roles … Good is that I get to have a wide breadth of exposure to lots of different problems, but bad is that it doesn’t articulate well with an academic career. (Reg_6)

Trusted partnerships

Most rural health researchers discussed the extensive research partnership and co-design work that they did, which required time and skill to build trust, rapport and engage partners:

… we’re essentially evaluating their model of care, so that takes a huge amount of trust, which doesn’t just appear overnight. (Rur_7)

People trust us, value us, and we are proving the path that you could be a good partner. (Rem_3)

The partnership basis of rural health research work was deeply rooted in direct service quality improvement. It involved researchers working with senior organisational representatives who could make change happen:

I work with a mixture of different types of people … for example, the [X] Aboriginal Medical Service, the CEO … is just incredibly passionate. Created a lot of change. (Rur_7)

I work with quite small regional hospitals … the small rural hospitals, with particular community health organisations including maternal child health and also some youth mental health services. (Rur_4)

Responding to a wide partnership base had the potential to shape a research program that involved multiple projects, for some:

… it means little projects – chipping away projects as opposed to looking at bigger picture stuff. (Rur_8)

Small, multidisciplinary research teams

Many rural health researchers described working in distributed sites and small local academic teams. These were described by most as highly collegial and tight-knit:

I guess the most enjoyable thing is that we are part of a small team. We know each other pretty well; we are very connected ... collegiality is very strong here. (Rem_3)

I found the working … it’s more like a family. When I was in [X city], I knew the faces for a couple of years, but I hardly had a chat with them …. (Rur_6)

However, most rural health researchers related that the limited research-trained staff base required them to lead the research process from start to finish:

I know from other colleagues working in other departments or other universities as well, they’ve got really large teams … we’re doing a lot of roles under the one title … things from recruiting through [to] doing community sessions, telling people about research … (Reg_3)

You have to be a leader in rural health research because generally in rural areas there are not a huge amount of researchers placed within those locations at least. (Rur_2)

… you do everything … from the beginning to the end. (Rur_5)

I’m there writing applications, I’m there writing ethics, I’m there writing all the things going … I don’t have a project at the moment that I’m not a CI [chief investigator] on … (Rur_8)

As a way of responding to limited resources, it was common for researchers to work with multidisciplinary, non-research trained staff and any interested students they could find:

… we always try to utilise the skill of the people who come here and [try to] develop a future project for them ... So, we’re trying to grow ... (Rur_6)

Everyone tends to be involved in something but they may not be leading something, they might just be involved in the periphery but they’re learning new skills. (Reg_2)

Distance and travel

Most described that rural health research involved extensive time for travel, including to distributed campus sites:

… We are so geographically isolated even from ourselves, we cross six campuses. From [X] in the north to [X] in the south it’s about a 10-hour drive between the two far flung campuses. (Rur_8)

For data collection and community engagement:

… there is a lot of travel ... you’re not doing a lot of driving every day, but when you do have to drive, it’s quite a significant chunk of driving … (Rur_3)

… I’m probably at [regional campus] about once a month or more so that’s seven hours out of the office in travel once a month. Then I cover – my role oversees programs in [W], [X], [Y] and [Z] so I’m on the road a fair bit for those … (Reg_2)

For face-to-face continuing professional development inherent to academic skills:

So one thing that really frustrates me is all of our training is done in [regional campus], which is a four and half-hour drive for me. (Rur_2)

… You’ve got to attend to professional development trainings or attending conferences [and] we have to drive three hours to the nearest city to catch a plane. (Rur_5)

The travel and time requirement were exacerbated for more remote staff:

I guess my current FTE [full-time equivalent] in research is really only probably about 0.1 and I feel like it should be 30 per cent of what I do and it’s not. A lot of that’s got to do with the demands on a rural and remote practitioner, with the travel that we do, it eats into our time. (Rem_1)

… just being able to go out into the field is a bit more challenging. (Rem_2)

Discussion

This is the first national, in-depth study about the field of rural health research based on the experience of the researchers involved. Rural health researchers strongly valued doing meaningful research that quickly and directly addressed health inequalities, impacted rural health and assisted the people around them. The researchers were mostly rural-based or rural-origin people, who were already trained for academic research or interested in rural health academic roles. This is consistent with other literature that identifies that rural place-based connection and rural training articulate well with rural supply36,49,50. It is possible that more rural health researchers could be recruited by building rural academic entry pathways to attract more rural-based clinicians or academically trained people, already based in rural areas. This may be facilitated by Master and PhD research scholarships, advertising and promotion of rural research projects and building PhD training options within rural-based organisations where it has the potential to add value to industry goals. Specific rural health doctoral training may assist with doing rural health research roles potentially because they attend to developing generalists fit for the rural research environment.

The present study’s results indicate that rural health researchers use diverse academic and local contextual knowledge and skills. The ‘generalist’ breadth of skills required is likely to be a product of several issues. Among these are the professional isolation of researchers (most >200 km or more from university campuses), the diverse rural community demand, working in small academic teams, spanning large geographic catchments and the novel methods to solve complex problems related to community and stakeholder interests. The generalist role has been described in rural health workforce literature but this is the first research to reflect it with respect to rural health academic work51,52. For many rural health researchers, there was a gap between the narrow scope of doctoral-level academic training and the skills needed for ‘real-world’ rural health research. A key issue is that early career researchers may be overexposed in rural academic contexts unless additional upskilling, real-time academic support and professional networking are available at rural sites. There are examples of tailored professional support programs for rural generalist doctors53; however, despite government investment in rural research positions, currently there is no entity regularly supporting generalist academic upskilling and professional support fit to rural academic practice.

Another key finding was that rural health research, as ‘place-based’ academic endeavour, has specific alignment with the principles of social accountability, where reciprocal relationships involve input and active participation of rural community and stakeholders within the research endeavour, for dual gains54. This may underpin the possibilities for research translation in this field, building on other literature about practice-based research networks23. However, the orientation of the field to achieving a ‘collective good’ may result in different processes and outputs than ‘place-neutral’ research fields, which are more able to focus on individual factors including the researcher’s career, a focused topic of individual interest, with the potential for excelling in academic research as a result. For example, the present study’s participants invested in building trusted partnerships over diverse rural communities and stakeholders over long distances. They undertook many small projects of limited resources, considered valuable for effecting local change. The partnerships took additional time to build trust, and such research, focused on responding to local problems, is not necessarily easily publishable. It is no surprise that the researchers both valued their generalist role and its potential, but equally suggested that responding to the community created tension over being ‘pulled in every direction’. They noted that the need to lead research was a product of working in small and isolated academic teams leading ‘everything … from beginning to end’. This was likely also a potential catalyst in other ways given they mentioned operating in a space with senior staff, such as CEOs of other organisations, potentially the envy of metropolitan researchers in large teams with narrower roles.

In some ways, researchers described the nature of their field to be in a degree of conflict with mainstream academic career expectations. Considering the potential value of generalist research that is socially accountable to rural places may require specific attention to building the field to a size considered reasonable for meeting demand and giving researchers a chance to fulfil all aspects with their roles with greater ease. Any capacity building strategies must recognise the generalist, socially accountable nature of this field and reward its different processes and outputs, such as researching in a breadth of areas, reputation amongst rural partners for contributing to rural health problem solving and potentially fewer major grants and research outputs, but more genuine and emerging community partners. Specific geographic weighting for rural health research career progression and grant funding applications is a consideration where these factors are complex to explain to metropolitan audiences. This is particularly in light of the fact that, to build their careers, rural health researchers are competing against metropolitan researchers who may be able to claim neater limitations on career opportunity that do not require a description of the multi-level factors that may impact on their research achievements. This is said in light of major research funding where rural health has had a dismal record. A simple geographic weighting would better reflect a value of research to Australians regardless of their postcodes and perhaps facilitate this field, which is enjoyable and produces evidence that fits heterogeneous rural contexts, systems and policies.

This study is a qualitative exploratory study only, and limited to 17 researchers working in the unique rural and remote context of Australia. Although the researchers considered that saturation was achieved, it is possible that other themes may have arisen with more interviews. Anecdotally, most rural health academics are females; however, the rural health academic workforce has never been formally characterised to determine the representativeness of the present study’s sample. Australia has a specific rural health research model (predominantly government funding for distributed rural sites) whereby caution is required with respect to translating the findings to other countries. However, rural academic researchers, as described in other countries, also work in isolation from each other over large distances8. Further research could expand or internationalise this exploratory study and consolidate the findings, including whether these themes are common to a larger sample of rural health researchers, including those at other career stages, and in other countries. The researchers did not identify specific themes related to working more remotely, although this issue and employment type could be expanded as an area of exploration in larger studies, perhaps sampling more purposively outside of the FRAME/ARHEN network (the sample included three researchers not employed in this network).

Conclusion

Overall, this national study is the first to describe the field of rural health research drawing on the experience of the researchers involved. The field is depicted by rural-based people training and taking up roles in rural academic work, doing place-based research that they value for its meaning to ‘people’ and ‘places’. Research occurs within trusted partnerships, across a generalist breadth, in small, multidisciplinary teams across extensive distances. The findings suggest that rural health research is highly rewarding, distinguished by a generalist scope and social accountability and its structure of small, isolated teams of limited resources. Strategies are need to grow capacity relative to the level of community demand, but these must embrace development of the rural academic entry pathway, the generalist breadth and socially accountable methods, as qualities that underpin the perceived value of this field for rural communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge FRAME and ARHEN for circulating the survey, and the Australian government’s RHMT program, which supported employment of the researchers who conducted this study. AC is supported by an Early Career Fellowship, NHMRC-funded Improving Health Outcomes in the Tropical North: a Multidisciplinary Collaboration (Hot North), grant identification number 1131932.

References

You might also be interested in:

2008 - Sharing after hours care in a rural New Zealand community - a service utilization survey