Introduction

Increasing the number of health professionals working in rural areas is a complex undertaking. Australia is not alone in implementing a range of strategies aimed at addressing this workforce maldistribution. Some strategies in Australia span decades and vary from individually initiated, locally based strategies in single communities1 to government-funded, broad-based strategies across several communities2, including the ‘rural pipeline’3-9, specialist outreach services10-13 and international medical graduates14. However, despite these efforts, addressing workforce maldistribution in rural areas remains a challenge for many professions and subspecialties, and continues to be the focus of much attention, as evidenced by policy development, collaborations, perspectives and conversations at conferences15.

The conceptual complexity of the term ‘rural’ adds to the challenge of addressing workforce maldistribution. Conceptual complexity refers to the ‘degree to which an idea … is difficult to understand, owing to the number of abstract concepts involved and the intricate ways in which they connect’16. The notion of ‘rural’ is acknowledged by scholars from varied disciplines beyond health, including geography, sociology and politics, as being conceptually complex, with ‘rural’ meaning different things to different people at different times for different purposes. Scholars in these disciplines portray ‘rural’ as an ‘expression of wider directions in contemporary society’17(p. 159) rather than being a fixed concept. Inherent in the notion of ‘rural’ is a ‘broad range of places, landscapes, people, practices and relationships between these’18 (p. 4), with representations of ‘rural’ being inherently shaped by values and discipline interests17,19. Thus ‘rural’ can be considered a socially constructed space with potential for competing interests.

Socially constructed meanings of the term ‘rural’ in healthcare workforce strategies reflect a preference for ‘rural’ to be reduced to quantifiable measures. These measures include town size, geographical remoteness and distance to services15. The strength of quantifying ‘rural’ is to provide the impetus for addressing inequitable access to health care and the evaluation of workforce maldistribution strategies. However, reducing the notion of ‘rural’ to these quantifiable categories overlooks the conceptual complexity of ‘rural’ and can lead to an increased focus on deficits and reinforce socially constructed meanings. Such a focus risks overlooking positive elements, while inappropriately problematising rural health care provision20, thus stereotyping rural areas as problematic environments for health care21. Although the importance of balancing deficit framings of ‘rural’ with more positive orientations is becoming recognised as an important aspect of addressing the maldistribution of the healthcare workforce21, a reliance on quantifiable measures prevails. Accordingly, like other professions and subspecialties addressing workforce maldistribution, dermatology has a tendency to frame ‘rural’ in quantifiable measures, implicit in which is a deficit perspective.

Dermatology was chosen as the focus of this research due to this being the subspeciality of two of the researchers. Workforce maldistribution strategies in dermatology reflect the ongoing challenge of expanding rural service provision, while simultaneously recognising that there is no one-size-fits-all approach for all communities, or for dermatologists or dermatology trainees. These strategies include rural and regional training opportunities22, government advocacy for rural health, dermatologists teaching in rural medical education, a committee for rural and regional services, meetings for rural dermatology and involvement in the federal government’s strategy of the Specialist Training Pathway23.

However, with this multiplicity of approaches and strategies, it can be difficult to conceptualise the complexity of rural health service provision as a whole. The notion of ‘tensions’ has potential for making sense of, and addressing, the complexity of the competing interests. Importantly, not all tensions arising from competing interests necessarily need to be resolved24 or even be viewed in a negative light. Space for ongoing rich discussion about the complexity of rural health service provision can be deliberately created by identifying, embracing and holding ‘tensions’ rather than necessarily resolving them, or trying to resolve them24. For subspecialities such as dermatology, this rich discussion has potential to be important for all people involved in addressing rural workforce issues, including those seeking to understand issues more deeply, those setting policy, those shaping policy, those implementing policy and those experiencing the implications of the policy.

Recognising the importance of informing such discussion, scope was identified for qualitative research to use a wide-angle, strength-based lens to explore the topic of dermatologists and dermatology trainees working in a rural area. The wide-angle aspect of the lens allowed the research to consider a multiplicity of situations. The strength-based aspect of the lens allowed the research to go beyond deficit-based approaches. The qualitative methodology allowed this research to transcend the tendency to reduce ‘rural’ to quantifiable measures and embrace the notion of tensions24.

Methods

The main research question was ‘How can the complex notion of working in a rural area be conceptualised by interpreting the perspectives of dermatologists and dermatology trainees?’, with the following subquestions:

- What core dimensions of the nature of working in a rural area can be interpreted from dermatologists’ and dermatology trainees’ perceptions and experiences?

- How can diversity within these core dimensions be interpreted?

- What ‘tensions’ within these dimensions can be interpreted in order to be deliberately held for ongoing discussion?

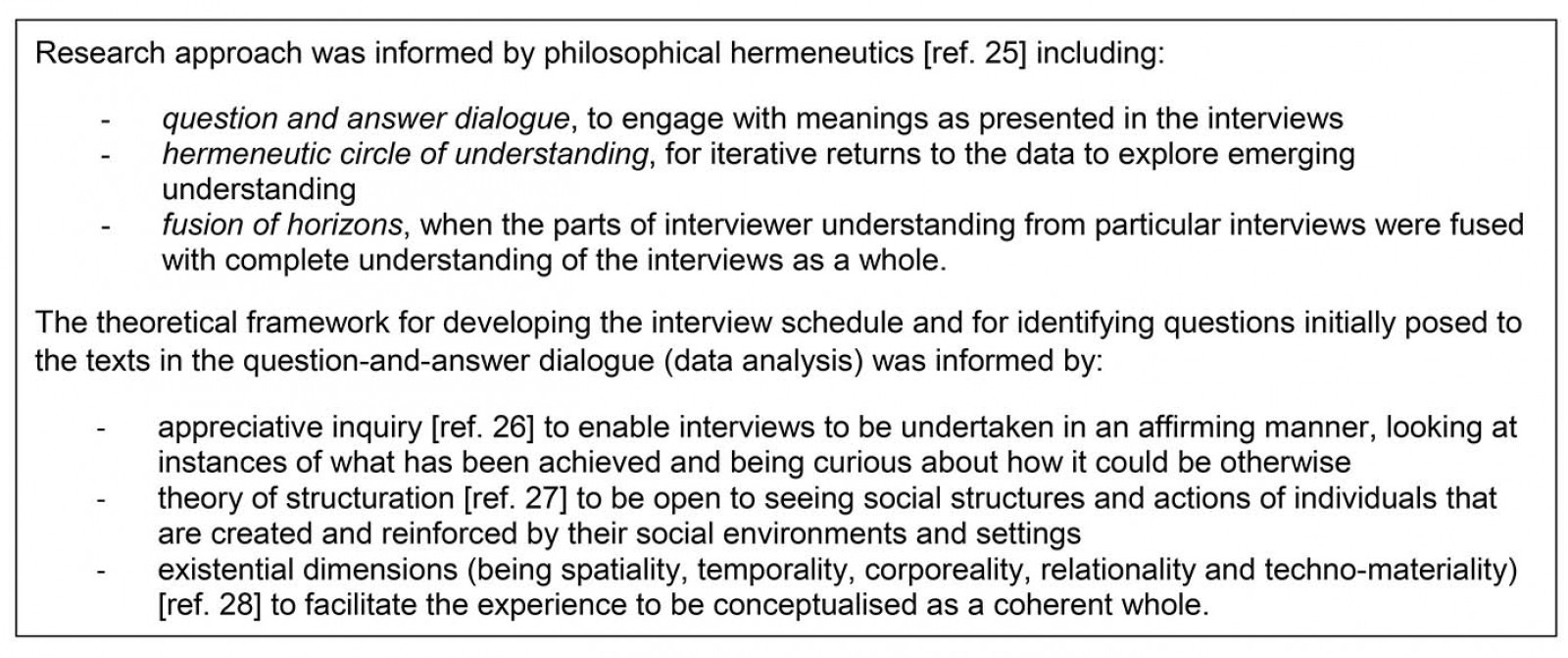

Philosophical hermeneutics informed the research approach of this qualitative research within the interpretive paradigm. Philosophical hermeneutics focuses on interpretation (rather than description), thus can make explicit taken-for-granted or implicit aspects and make visible inherent tensions. The team comprised a dermatology trainee, dermatologist and qualitative researcher. The theoretical framework was informed by a lens of appreciative inquiry, theory of structuration and existential dimensions (Box 1). This theoretical framework was chosen to access conceptual complexities.

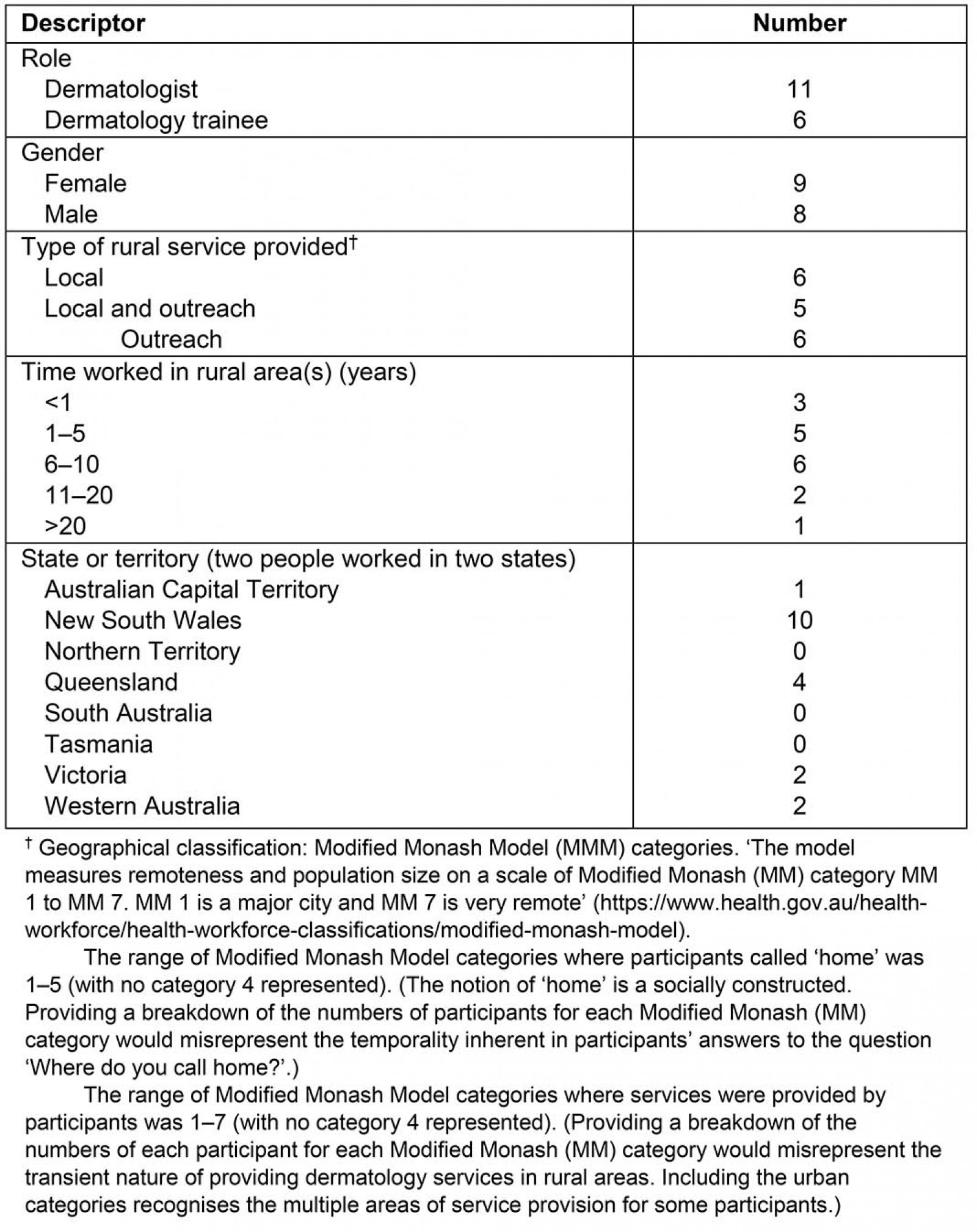

Participants were purposively sampled to recruit dermatologists and dermatology trainees who had experience providing services in rural areas. All dermatologists and dermatology trainees who responded to the recruitment material indicating an interest for an interview were included in the research project. Recruitment of dermatologists and dermatology trainees yielded 17 participants. Of these, 11 were dermatologists and six were dermatology trainees. The diversity achieved in the sample is shown in Table 1.

Data collection was undertaken through conversational-style semi-structured participant interviews undertaken by telephone (n=16) or face-to-face (n=1). Interviews lasted between 15 and 45 minutes. While noting the potential limitation that not all states and territories were represented, sufficient data were collected to enable an ongoing ‘question and answer dialogue’ during data analysis, thus reaching a point in time where the dialogue was complete and the research question could be answered (this aligns with the term ‘data saturation’, which may be used in other qualitative research approaches). Interviews were audio-recorded and a professional transcribing service was used for transcription. All transcripts were checked for accuracy. To ensure anonymity, participants were allocated pseudonyms of three randomly allocated series of letters not corresponding to the initials of any participants.

During data analysis, interview data were managed by the NVivo v12 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home). Data were initially coded descriptively, with iterations moving towards more conceptual themes. Interpreted through this dialogical and iterative process were four key themes (dimensions), subthemes (characteristics of the dimensions) and implications (tensions). Quality criteria for this research included rigour, authenticity and credibility.

Box 1: Research approach and theoretical framework25-28.

Box 1: Research approach and theoretical framework25-28.

Table 1: Participant demographics

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was received from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee, reference number H-2018-0156.

Results

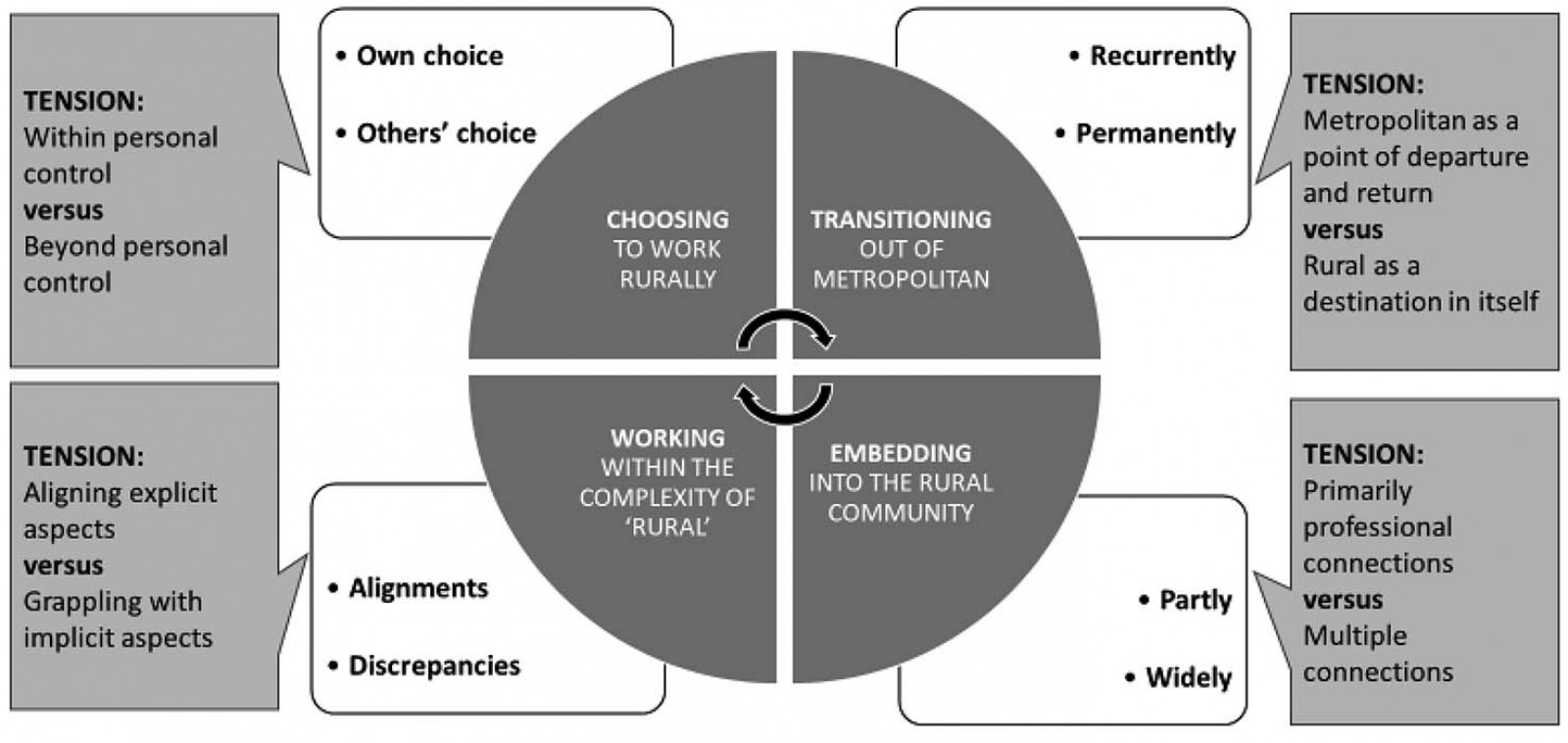

A diagrammatic overview of the findings is provided in Figure 1. Four dimensions are positioned centrally in the conceptualisation, interacting in a temporal manner: choosing to work in a rural area, transitioning out of a metropolitan area, embedding into the rural community and working within the complexity of ‘rural’. Within each of these four dimensions are two characteristics. These characteristics reflect diversity within each dimension. Tensions arising from the diversity within these characteristics are highlighted. As the dimensions and their characteristics tend to transcend being either a dermatologist or dermatology trainee, these roles are not identified with the pseudonyms but are evident at times in the text, when necessary for meaning and context. Pseudonyms are withheld where the quote could lead to a participant’s identification.

Figure 1: Model conceptualising dimensions of working in a rural area – perspectives of dermatologists and dermatology trainees.

Figure 1: Model conceptualising dimensions of working in a rural area – perspectives of dermatologists and dermatology trainees.

Dimension 1: Choosing to work in a rural area: When people exercised their own choice to work in a rural area, they did so for a range of different reasons. Whether it was about seeking a rural lifestyle or getting away from a metropolitan lifestyle, their decisions were within their control.

I just wanted to be in a location where I wasn’t spending half my day in traffic. (FPZ)

Earlier rural experiences at various stages in their life and training could influence this choice, and opportunities could facilitate future choice.

I suppose growing up in a rural area I always felt quite passionate about [working rurally] once I’d graduated. (ZYI)

[It’s] on a voluntary basis … to go [to a particular rural area] every month with the consultant … It does, I suppose, put a seed in our brain for the future. (HZQ)

In contrast some people, particularly trainees, had no choice regarding where they worked. They worked in rural areas through other’s choice that could be beyond personal control. Despite the lack of control over specific destinations, the experiences of working rurally could ultimately lead to positive results for dermatology services in rural areas.

I was posted here [regional area] as a … dermatology registrar against my will … then once we were here … [we were] very happy with the lifestyle … so we ended staying. (Pseudonym withheld)

However, being required to comply with others’ choices could have impacts beyond training in the rural area. Importantly, the impact could extend to family and beyond to personal safety.

I didn’t actually get to pick where I was going. … and it was quite significantly stressful I think for everyone involved … initially I would drive out to [rural area], I thought that was getting a bit dangerous because I used to get really tired and I have fallen asleep a couple of times on the road and thought it was a huge risk ... I just got quite conscious that life is fragile and short. (Pseudonym withhold)

The tension related to choosing to work rurally being within personal control or beyond personal control highlights a need to consider individual agency for choosing to work rurally (in a manner that ensures safety and considers support networks) and balance this with a need to ensure dermatologists and dermatology trainees have experience in rural areas (as a basis for future individual choice to provide services in rural communities).

Dimension 2: Transitioning out of a metropolitan area: People providing outreach services are recurrently transitioning out of metropolitan areas for their work in rural areas. In such instances the gravitational pull back to their metropolitan life appears tangible and metropolitan is a point of departure and return.

You need to be able to go in and do your work and leave again. (UWR)

When they leave the rural community to return to their metropolitan home, they need to have strategies in place to deal with their absence.

There are more phone consultations, a lot more phone follow-up, ‘how are you going’, because I can’t review them. … You kind of rely on the GP to triage it better, rather than waiting for me to come in [particular number of] months. (PJT)

While they take work back to their metropolitan area with them, they also take back patient gratitude.

I think that the population in rural areas just don’t have the luxury of having a choice and so they’re always grateful for any specialties that come and provide service in their area. (KEJ)

Moving to live and work in a rural area, involved permanently transitioning out of metropolitan, where rural was a destination in itself. A practice needed to be established.

I had to find rooms, I had to find staff, I had to liaise with the local GPs, I had to buy equipment … I won’t say it was easy, I won’t say it was difficult, but it had its challenges. (VBC)

Benefits went beyond work.

It was the best move we made, it’s a great place, we brought up our children here. We are really part of the community, made a lot of friends. (MQN)

The tension between metropolitan as a point of departure and return and rural as a destination in itself relates to the need to recognise the gravitational pull of metropolitan to be the point of departure and return and ‘energy’ required to overcome it to enable rural to be a destination in itself.

Dimension 3: Embedding into the rural community: When people provided intermittent outreach services they tended to embed partly through primarily professional connections in the community. Professional and patient relationships, while valuable to these connections, could take time and sensitivity to develop.

Trying to build relationships … working with the local people on the ground …you’re in their home territory, on their ground. … It probably took me a year or two to find my feet and try and work out what was going to work best for the local population and me. (WXE)

Insight into the social fabric of the community could be gleaned, but there was sense of being on the periphery.

I get the sense that it’s a good [community], it’s a really nice community feel when you go there. … These people like to live there because it’s nice and quieter. (PJT)

Those embedding widely experienced multiple connections within their communities related to work and everyday life.

We have very close relationships with all the general practitioners in the area … they can contact me any time if they have any queries. (YCV)

When I go into [shopping centre] if I don’t see ten of my patients walking down the aisles, I’m not very observant because they’re all there. (VBC)

Sometimes local people assisted with embedding widely.

There’s a lady whose job it is to get medical specialists to settle in [rural area] and keep them happy. (TLB)

The tension in this dimension arises from the scope to have either primarily a professional connection or many connections in the rural community, thus foregrounding relationships between dermatologists or dermatology trainees and people living in rural communities.

Dimension 4: Working within the complexity of ‘rural’: Aligning different people, policies and strategies within rural practice is important for facilitating the provision of dermatology services. Aspects to be aligned in order to provide rural services include personal values, rural community healthcare needs, relationships with colleagues and governmental responsibilities.

I feel like I have an ethical obligation to help out … with the dermatology workforce shortage. (IOF)

[The public health system needs] to support [dermatology service to rural and remote areas] with administrative staff, with nursing staff, with junior medical staff and adequate remuneration for all of those people including the dermatologists. (VBC)

I think [the] future depends on how the government with the rural funding sees the need. (PJT)

Other aspects underpinning provision of services are less tangible and can be conceptualised as discrepancies of shared understanding. Aspects such as the definition of ‘rural’ are hard to conceptualise due to their complexity. While the lack of shared understanding can enable an inclusive view of ‘rural’, it can challenge clarity about rural identity.

[Rural area] is considered outside [metropolitan area] and therefore considered rural. (KEJ)

We’re regional and it’s still a city, even though you call it rural. (NFH)

Yeah, it’s probably not … super rural, because [particular number of] hours from the city is not as remote as say other parts of [state]. (PJT)

They sort of feel rural. (TLB)

Other discrepancies are subtle and easy to overlook, such as the taken-for-granted language portraying ‘rural’ differently. Words can portray ‘rural’ as with positive possibilities where people could be invited to work.

There would be more than enough work for people to come and work here fulltime. (ZYI)

It is actually really rewarding. (HZQ)

Alternatively, words can portray rural practice as being beyond normal expectations to go outside their comfort zone (requiring them to be exposed, enticed or bonded).

We’re exposing our junior trainees to life away from the city. Most of our trainees at least do some rural rotations and get some exposure. (UWR)

I think … that'll entice people to do more of these rural clinics. (HZQ)

I don’t think [dermatologists] … are necessarily going to come [to rural areas] until the cities are overflowing. I think you have to bond them as part of their training. … (CDG)

We really need to start sending people out there ... (IOF)

Inherent in this dimension is tension between both a focus on aligning explicit aspects of ‘rural’ and being open to making visible and grappling with implicit aspects of our representations of ‘rural’.

Discussion

Aspects of the findings from this research resonate with literature exploring workforce maldistribution strategies, including issues associated with autonomy for choice to work rurally5, the positive influence of rural background for choosing to work rurally4,7,8,29, the role of local communities in supporting doctors as they begin in the rural area1,30, attractive and challenging aspects of rural practice6,31-33, and the importance of working with local general practitioners13. However, as well as resonating with these aspects of the literature, the conceptual model produced through this research (Fig1) provides a meta-view that allows them to be seen in relation to each other.

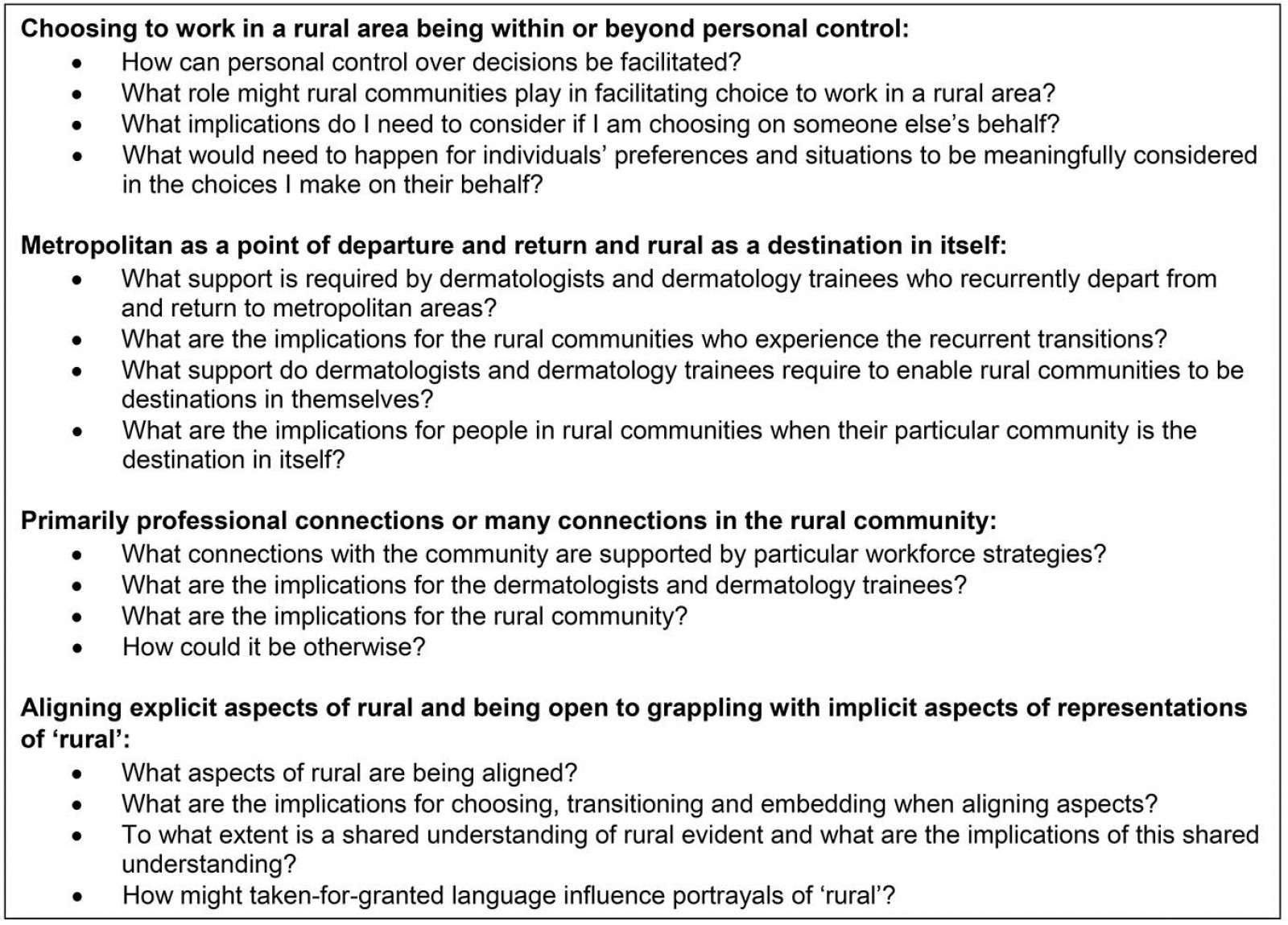

The model’s meta-view also has scope to support critical awareness of the complexity of the notion of working in a rural area. Awareness of such complexity is important for those participating in discussions about workforce maldistribution strategies. Depending on the purpose of the discussion and the inclination of those involved, different degrees of critical awareness can be employed. First, there is potential to conceptualise and locate literature within the meta-view with minimal critical awareness or critique of the way literature socially constructs the notion of ‘rural’. For example, findings from other research could be mapped to dimensions, characteristics and tensions within the model in order to identify situations and issues in need of further exploration, particularly within a geographical-spatial classification framework. Second, it could be used as a trigger for individuals to share their experiences and stories of rural practice, and in doing so enable others to understand and critique how these experiences fit within the complex social construction of ‘rural’. Relevant social constructions might include consideration of sociopolitical characteristics, such as census-based data and land use (including tourism or primary production), as well as experiential considerations, such as what people think of as rural34. Third, the meta-view model has potential to encourage inherent competing interests to be made explicit when discussing different policies and strategies. In doing so, strategies such as outreach services and ‘rural pipeline’ can be seen as reference points for each other, thus enabling both styles of practice to be kept in mind when making decisions about one or the other. Finally, the meta-view can provide a source of critical reflection within and between different groups of people, including those who have responsibility for choosing where, when and by whom services are delivered; those who provide the services; those who live in the communities receiving the services; and those who develop and fund workforce strategies. Examples of reflective questions are provided in Box 2.

Making explicit the theoretical basis underpinning the questions in Box 2 encourages a higher level of critical awareness and enables knowledge from other disciplines to be deliberately incorporated into discussions about workforce strategies. Questions related to the tension of choosing to work rurally being within personal control or beyond personal control are underpinned by Bandura’s social cognitive theory of human functioning35. This theory highlights the importance of decision makers being cognisant of the social power they hold and attending to consequences of their actions while simultaneously recognising the ambiguities inherent in moral judgements. In relation to questions about the tension between metropolitan as a point of departure and return and rural as a destination in itself, Giddens’ theory of structuration encourages awareness of the risk of inadvertently reinforcing social structures and actions that contribute to workforce maldistribution27. This awareness identifies a potential paradox whereby the gravitational pull of metropolitan becomes more difficult to overcome by the constant return to metropolitan. Questions about the tension in having a primarily professional connection or multiple connections in the rural community draw on Gergen’s notion of ourselves as relational beings36, whereby knowledge of and knowing ‘rural’ is the outcome of relational processes. Social geography theorists caution against assuming conceptual stability of ‘rural’. This caution informed the questions relating to the final tension, that is, the tension between both a focus on aligning explicit aspects of rural and being open to making visible and grappling with implicit aspects of our representations of ‘rural’. Dymitrow and Brauer37, for example, noted that reliance on geographical classifications can lead to desensitisation of their limited nature and create an artificial filter for understandings of ‘rural’. They proposed a need to pay greater attention to the ‘reality’ inadvertently drawn by socially constructed conceptualisations of ‘rural’. Their proposition has relevance for addressing the deficit framings of ‘rural’.

In accordance with Wulff’s notion of tensions24, the tensions related to the complexity of addressing rural workforce maldistribution can be embraced and held for ongoing discussion rather than seeking to superficially resolve them. The implications of embracing rather than seeking to superficially resolve tensions can be the focus of further theorising and ongoing research. Readers are also invited to explore other theories that can enrich discussions of rural in relation to working in a rural area and workforce maldistribution.

Limitations of the study are considered in relation to intentions of philosophical hermeneutics. The intention was not to achieve equal representation across all demographic categories, but rather to access diversity of experiences and perceptions. However, as not all states and territories were included in the participant group, access to diversity of experiences and perceptions was potentially limited. Further, the intention was not to provide a definitive answer or ensure generalisability. Rather, transferability, determined by the readers, was sought. Using their own situations as reference points, readers are invited to engage with the findings and discuss issues raised for them through this research.

Box 2: Reflective questions for consideration of those involved in developing strategies addressing rural health workforce maldistribution.

Box 2: Reflective questions for consideration of those involved in developing strategies addressing rural health workforce maldistribution.

Conclusion

The conceptual model produced through this research provides a meta-view that makes explicit tensions inherent in addressing rural workforce maldistribution. The accompanying reflective questions enable these tensions to be deliberately embraced for ongoing grappling and discussion. Critical awareness about competing interests can be further enhanced by engaging with social science theories.

References

You might also be interested in:

2004 - Cooperative knowledge-making with female and male rural doctors