Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and, as of 2018, account for more than two-thirds of all new HIV diagnoses in the USA1. The most common way MSM acquire HIV is through unprotected anal sex, which includes not using condoms or prevention medications like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)1. PrEP is a medication containing tenofovir and emtricitabine that a HIV-negative person can take daily to significantly reduce their chances of acquiring HIV. When PrEP is taken consistently, it is up to 99% effective and is even more effective in combination with condoms2. Improving education surrounding the utilization of PrEP among key populations affected by HIV could significantly decrease the number of new infections. Despite continued technological advances and new medications available to increase HIV prevention measures, there are still numerous barriers to acquiring these preventative medications. A few of these barriers, particularly for MSM in rural areas, include lack of knowledge about the availability of PrEP, concerns about insurance coverage, lack of providers in their area, transportation issues, and stigma/homophobia surrounding accessing HIV-related services3.

Experiences of MSM in rural areas

The experiences of MSM living in rural areas are different than those living in more urban areas, particularly for those who identify as gay, bisexual, or transgender, as rural areas are less likely to have supportive, same-gender-loving communities and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT)-friendly social spaces4. For non-heterosexual MSM, not having LGBT-supportive communities can lead to internalized stigma, loneliness, fear of being ‘outed’ by friends and family and the pressure to adopt heterosexual norms4. Additionally, the lack of comprehensive sexual health education in rural areas limits the ability for LGBT-identifying MSM to receive sexual health information that directly pertains to them, as it is frequently focused only on sexual behaviors between cis-gender men and women5. When compared with MSM in urban areas, MSM in rural areas are less likely to be tested for HIV, receive condoms, or have information about and access to PrEP6. A recent study found that one out of eight MSM who were eligible for PrEP lived more than 30 minutes from a PrEP provider (in a ‘PrEP desert’), with the odds of living in a PrEP desert significantly increased for those living in the South and in non-metropolitan areas7. Qualitative research has found that rural MSM report multiple barriers to accessing PrEP, including stigma and reduced access to LGBT-sensitive medical care8.

Furthermore, HIV funding and prevention efforts have largely focused on urban areas due to a higher prevalence of HIV. However, MSM in rural areas are still significantly affected by HIV and have less access to HIV services as areas become more remote and isolated4. There are fewer services in rural areas because it is not as cost effective for organizations to operate in a lower-density area, increasing the need for technology-based service delivery4. Telehealth, the idea of delivering medical services or prevention information by technology, has become more feasible in recent years as internet speeds and connectivity have improved in rural areas and MSM are relying more on technology to build their social networks4,5,9. MSM living in rural areas have suggested that online methods of health outreach are preferred10.

Dating application use

In recent years, an increasing number of people have turned to internet-based dating websites or applications (apps) to meet potential sexual partners, find friendships, and pursue romantic relationships. Recent research has found that 30% of all US adults, and over 50% of those who have never been married, have used an online dating site or app11. The growth in dating app usage has coincided with an increase in positive attitudes toward online dating and a decrease in the previously associated stigma. As many as 80% of Americans believe online or app-based dating is a good way to meet people and 61% feel it is easier and more efficient than meeting someone through in-person methods12.

One group that has received considerable research attention specific to dating app usage is MSM, who were early adopters of using the internet to find partners13. A 2014 study reported that MSM accessed dating apps nearly 22 times per week while their non-MSM counterparts accessed them eight times per week14. More recently, one study found that 78% of MSM reported at least some use of dating apps, while over 55% were frequent users15. A Pew internet study found that 55% of all US adults that identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) have used dating apps (compared to 28% of straight/heterosexual individuals) and that 28% of partnered LGB individuals met their current partner online (compared to 11% of straight/heterosexual individuals)16. Grindr, the most popular app for MSM, has reported over three million daily users worldwide17.

Many men access dating apps on a regular basis to find sexual partners, start new relationships, or meet new people18. Dating apps could be particularly advantageous for MSM in rural areas because they provide a sense of anonymity in areas that may be less welcoming to LGBT individuals. Online dating also allows users to view demographic information, personality information and to chat with potential partners prior to meeting in person, which increases a user’s sense of control and safety over dating19. Another benefit to dating apps, particularly in rural areas where establishing a sense of community is important, is that strong friendships can be created19. These findings suggest that dating apps could facilitate the creation of stronger, new social networks of people who share similar interests. Understanding the positive aspects of dating apps helps to gauge how this technology could be leveraged to improve the health outcomes of MSM in rural areas.

While dating apps can lead to positive relational outcomes, they may also be associated with negative health behaviors. MSM who utilize the internet and apps to find partners may engage in more risky sexual behaviors13, including increased number of partners, frequency of condomless sex, and likelihood of being diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection20. However, those who use Grindr are more likely to use PrEP – suggesting that they are taking steps to reduce the impact of these risky behaviors20. More research is needed in this area, however, as many studies assessing dating app use and sexual risk behavior have focused on MSM in urban areas13,18,21. The present study is unique because it examines dating app use, sexual behaviors, and PrEP attitudes among rural residents.

Study aims

This article will examine the role of dating apps in the lives of rural MSM, how apps may contribute to sexual risk, and how they could be used to improve HIV prevention. Utilizing a mixed-methods approach, the study sought to answer the following research questions:

- What is the frequency and use of dating apps among MSM in rural areas?

- What perceptions do MSM in rural areas have of dating apps?

- What is the relationship between dating app use and sexual behaviors?

- What is the relationship between dating app use and PrEP usage, interest, and attitudes?

Methods

A mixed-methods research design was used to address the main study questions by triangulating survey data with more in-depth data from semi-structured qualitative interviews. This approach was chosen to produce a more comprehensive and thorough understanding of dating app usage among MSM and the opportunities these apps may have within the public health field.

Recruitment and participants

Individuals were eligible to participate if they (1) considered themselves to be a man who dates or has sex with other men (including both cis-gender and transgender men), (2) lived in a non-metropolitan area of the Southern USA (self-identified; examples of large metropolitan areas were provided), and (3) was aged at least 18 years. There were no requirements related to sexual orientation. Participants were recruited through a variety of social media accounts and community listservs (eg local LGBTQ groups, university LGBTQ groups) to complete an online survey and received a $25 e-gift card in exchange for participating. After completing the survey, participants (n=85) indicated their interest in completing a qualitative interview. Interested respondents were contacted by research staff to schedule an in-person or phone interview. A total of 20 participants completed qualitative interviews and received an additional $25 e-gift card.

Data collection and measures

Quantitative survey: The survey was conducted using Qualtrics, an online survey platform. The assessment contained nearly 150 items addressing a variety of factors, including technology use, sexual behaviors, online dating, mental health, healthcare utilization, and attitudes/knowledge about PrEP use among MSM. The survey took approximately 20–30 minutes to complete.

Dating habits and application use were assessed through a variety of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions pertaining to having a current dating app profile, ever having used a dating application, and whether or not the respondent was currently in a relationship. Respondents were given a list of seven popular dating sites/applications and asked to choose which of them they had used.

Sexual behavior was measured by participants specifying the number of sexual partners they had in the previous 3 months, whether or not they had a primary partner, the number of partners they communicated with online before speaking in person, and the number of times they had anal intercourse (either receptive or insertive) with a primary, HIV-negative, HIV-positive, or unknown status partner. They were asked to enter the number of times in the previous three months that they used a condom with the partner type they specified (primary, HIV-negative, HIV-positive, or unknown status).

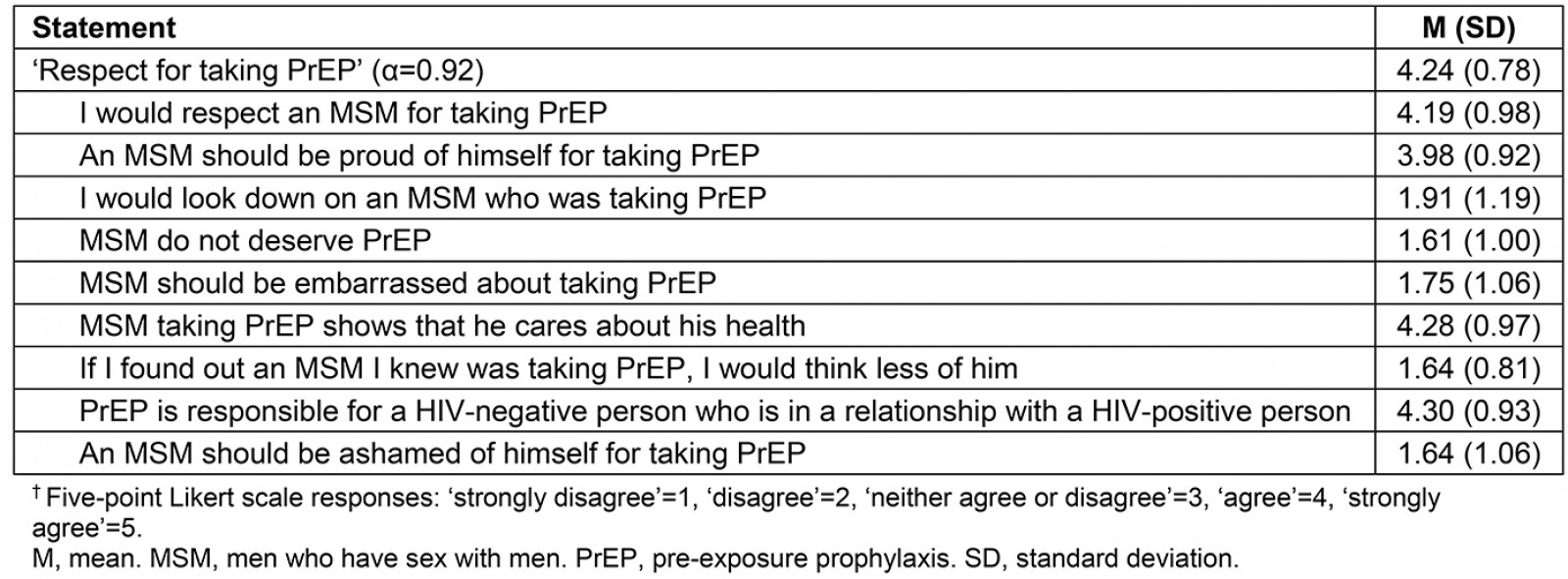

Three PrEP questions were asked: ‘Have you ever heard of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, or 'PrEP', a daily pill you can take to help prevent getting HIV?’, ‘Have you ever received a prescription for PrEP?’, and ‘What is your level of interest in taking PrEP?’ with scores ranging from 1=’very uninterested’ to 5=’very interested’. Participants also rated 26 different statements using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, that examined their beliefs, perceptions, and attitudes toward PrEP. These items comprised five different subscales, including ‘Respect for taking PrEP,’ ‘Support for PrEP financial assistance,’ ‘Predicted risk compensation,’ ‘Perceived community benefit/support for access,’ and ‘Predicted adherence’. This scale has been relatively untested and the original article found adequate reliability for the subscales22; however, a reliability analysis for this sample yielded alpha scores of <0.70 for most subscales, so they were not considered to be reliable. The present study used the ‘Respect for taking PrEP’ subscale (9 items; α =0.92), summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: PrEP attitudes, measured using the ‘Respect for taking PrEP’ subscale (n=89)†

Qualitative interviews: Interviews were conducted by two research staff with experience discussing sexual behaviors and sexual and gender minority health (DL and NT) using a semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide was collaboratively developed by both clinical and non-clinical research team members of differing ages, genders, and sexual orientations (DL, NT, NH, and CL). To build trust, participants were given the option of completing the interview in person at a location of their choosing or by phone. Respondents did not have to disclose their name and the interviewers worked to establish respondents as equals in the research process. At the start of the interview, participants (n=20) reviewed the consent form and were asked to give verbal consent. Each interview was audio-recorded and lasted 30–90 minutes. Participants were asked about a variety of topics, including their experiences with and perceptions of dating apps, dating within their geographic area, their relationship history, the role technology plays in their health, and their experiences with sexual health education. Example questions included, ‘Do you use different dating apps for different purposes?’ and ‘What would you say is the role of technology in supporting your sexual relationships?’ Interviewers regularly met with the research team to discuss emerging themes and experiences, conducting further interviews until saturation was reached, operationalized in this study to mean until no new data specific to the research questions emerged.

Data analysis

Quantitative survey: Frequencies and descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics, dating app use, sexual behaviors by partner type, and PrEP knowledge/beliefs/interest. An overall condom use percentage was calculated for each partner type by dividing the total number of times they reported using condoms by the total number of times they reported sex. Independent samples t-tests were used to examine the associations between having used a dating app/current dating app use and number of sexual partners, having ever used a dating app/current use of dating apps and ‘Respect for taking PrEP’ scores, and having ever used a dating app/current use of dating apps and interest in taking PrEP.

Qualitative interviews: Each of the semi-structured interviews was transcribed verbatim and analyzed using QSR NVivo v11 (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com). The qualitative data were approached using an interpretivist epistemology, such that the research questions were answered by constructing knowledge based on the social construction and lived experiences of the respondents, while also acknowledging and being reflexive of the positioning of the research team within the research process. Constructionist grounded theory principles guided data collection, codebook development, and analysis. During codebook development, a diverse team inclusive of research staff of differing genders, sexual orientations, and ethnic backgrounds engaged in open coding to identify inductive codes, meeting weekly to discuss until no new codes were identified. The resulting codebook included a total of 47 unique codes. Then, three teams each composed of three research staff applied five to seven codes, per cycle, to all transcripts. Team members first independently coded the interviews and then met with the team to discuss the analysis until complete consensus was reached for each code. The authors then conducted axial and selective coding, meeting regularly to discuss the analysis and development of this manuscript.

Due to their relevance to the topic at hand, the following three codes will be examined in this article: acceptability/success of dating apps, perceptions of different dating apps, and technology’s role in health. DL led codebook development and qualitative data analysis with involvement from NT, NH, and CL; LB led axial and selective coding for this specific analysis; and all authors were involved in code consensus, discussion and writing.

Ethics approval

All study procedures were approved by the University of Georgia’s Institutional Review Board (ID#00002187).

Results

Quantitative results

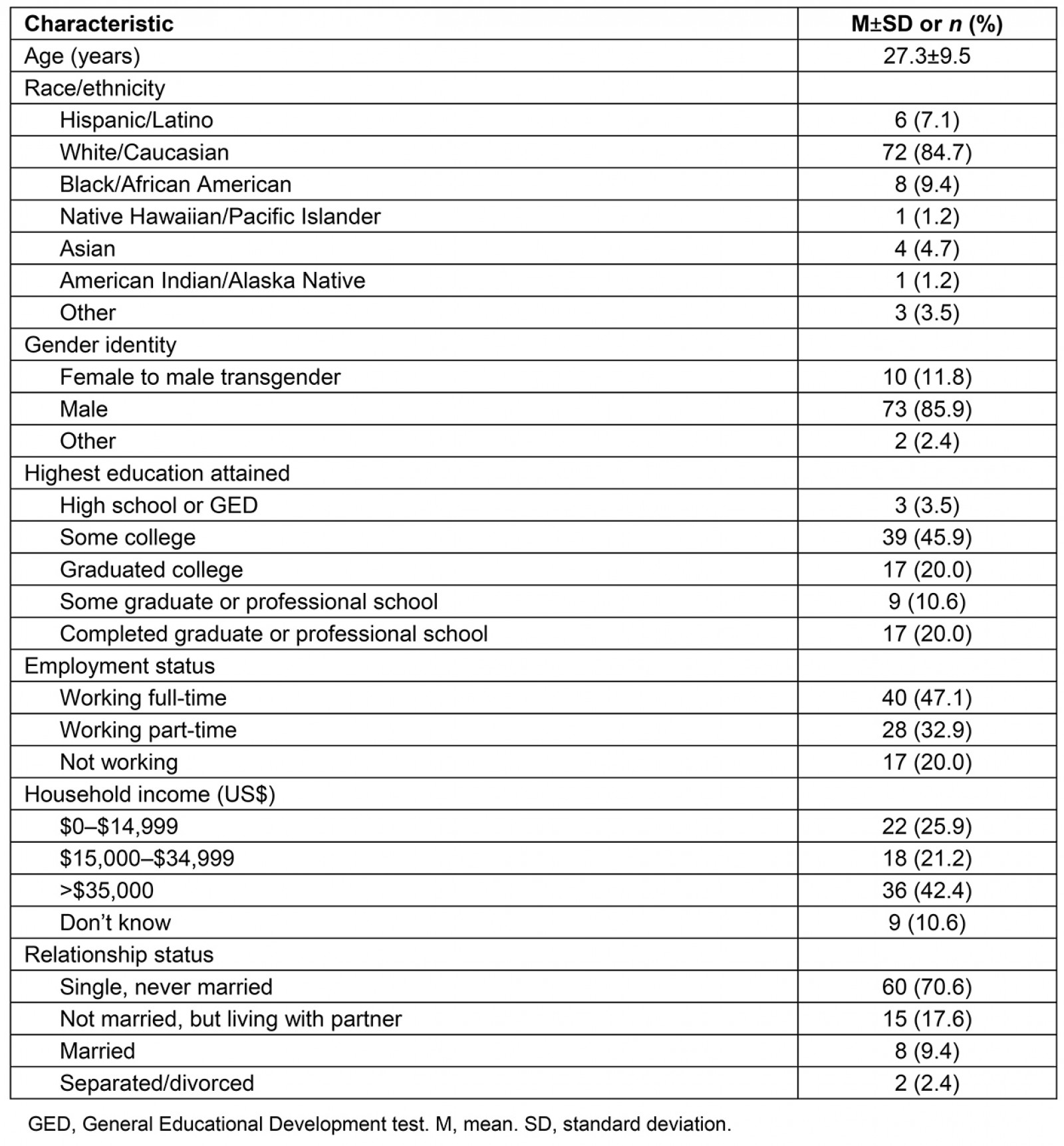

Demographics: The survey sample included 85 MSM, of which 10 (12%) identified as transgender. A majority of the sample was white (85%) and the mean age was 27.3 years. Almost all individuals (98%) self-reported as HIV-negative. A total of 39 participants (46%) were in a committed romantic relationship. Of those who were not in a relationship, 34 (74%) were currently looking for a romantic partner. All participants reported that they dated or had sex with other men, and data were not collected regarding sexual orientations of survey participants. See Table 2 for additional participant characteristics.

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of participants (n=85)

Dating app use and sexual behavior: Of the entire sample, 74% (n=63) had used an online dating app or website and 75% of these individuals (n=47) currently had an active profile. Of those who had used dating apps, Grindr was used by the most people (92%, n=58), followed by Tinder (57%, n=36), Scruff (53%, n=33), OkCupid (49%, n=31), Craigslist (38%, n=24), Jack’d (32%, n=20), and Manhunt (25%, n=16). Of the 39 participants in a committed relationship, 16 (41%) met their current partner online.

The relationship between having a current dating app profile and number of sexual partners was statistically significant: those who currently had a profile had more sexual partners (mean (M)=2.55, standard deviation (SD)=2.53) than those who were not using dating apps (M=1.25, SD=1.06) (t=–2.87, p<0.01). A similar association was found between ever having used a dating app and number of sexual partners (t=–3.65, p<0.01), with those who had used a dating app having more partners (M=2.22, SD=2.31) than those who had not used an app (M=1.05, SD=0.65).

In the previous 3 months, 72 participants (85%) had at least one sexual partner. The number of sexual partners ranged from 0 to 12. Of those who reported partners, 31% (n=22) did not have someone they considered to be a primary partner. Most individuals with a primary partner reported that their partner was HIV-negative (n=43, 81%), with fewer having a partner with unknown HIV status (n=7, 13%) or a HIV-positive partner (n=3, 6%). Among those who had sex with a primary partner, average condom usage percentage was 38%, but this varied according to HIV status; it was highest for those with a HIV-positive partner (89%), followed by those with partners with unknown HIV status (61%), and lowest for those with a HIV-negative partner (28%). Respondents were also asked about condom use with partners other than primary partners. Average condom usage of those who had sex with a HIV-positive partner (n=6) was 80%. For those who had sex with a HIV-negative partner (n=43), average condom usage was 52%. Respondents who did not know the status of their partner (n=19) had an overall condom usage of 58%.

PrEP use and attitudes: Most of the participants (74%, n=63) had heard of PrEP before. Most (93%, n=79) had never had a prescription filled for PrEP, although 44% (n=37) were ‘interested’ or ‘very interested’ in taking PrEP. When asked how easy it would be to get a prescription for PrEP, only 27% thought it would be ‘easy’ or ‘very easy.’ Those who had ever used a dating app had significantly higher interest in taking PrEP (M=3.35, SD=1.07) compared to those who had never used one (M=2.71, SD=1.35, t=–2.21, p<0.05). Similarly, individuals who currently used apps had higher interest in taking PrEP (M=3.55, SD=1.02) than those who did not currently use apps (M=2.75, SD=1.00), t=–2.74, p<0.01). A significant relationship was found between having ever used a dating app and higher ‘Respect for taking PrEP’ scores (t=–2.45, p<0.05), such that those who had used a dating app had higher scores (M=4.44, SD=0.62) than those who had never used an app (M=3.91, SD=0.92). Current dating app users also had higher ‘Respect for taking PrEP’ scores (M=4.63, SD=0.47) when compared with non- users (M=3.88, SD=0.68, t=–4.82, p<0.001).

Qualitative results

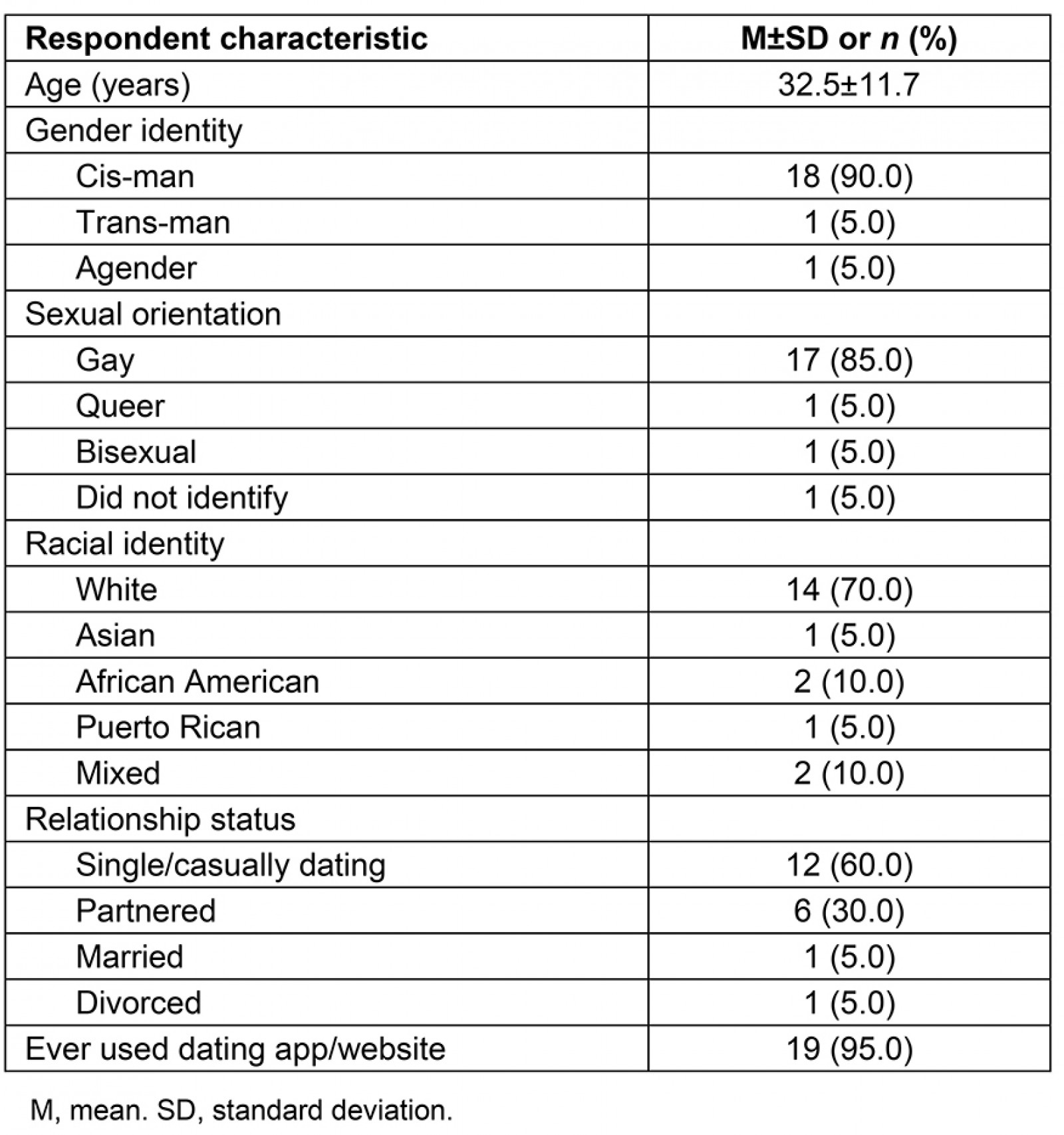

Of the 20 interview respondents, a majority (n=18) identified as cis-gender men, as gay (n=17), and as white (n=14). Only one person had not used a dating app/website and 12 were either single or casually dating. The remaining demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 3. The three main themes of interest, including the benefits to utilizing dating apps, perceptions of different dating apps, and the role technology plays in one’s health, are discussed further below.

Table 3: Demographics of interview respondents (n=20)

Acceptability and accessibility – ‘the path of least resistance’: Respondents discussed dating app usage and how technology has changed the traditional course of meeting people. Many individuals discussed how apps have become more acceptable in recent years and can facilitate relationships with people ‘who are also interested in the same things that you are’ (participant (P) 1, age 23 years). Another participant stated, ‘that technology allows you the opportunity to meet a wide variety of people from different places and different backgrounds that you may never have had contact with before’ (P3, age 43 years). One individual explained how apps can make it easier to understand people’s dating intentions:

I think in the past before technology existed, it was a lot harder to have hook ups because you would have to know someone personally and then ask them. And at that point it’s very awkward umm if they are not looking for the same thing that you are, so I think the added layer of convenience and anonymity that dating apps provide has made it a lot easier. (P1, age 23 years)

The ability to ‘go online and be anonymous allows people who live in rural areas the opportunity to connect with people across the country or even in their own states’ (P3, age 43 years). The added layer of anonymity reduces the chances of MSM being outed in smaller communities and also makes uncomfortable situations, such as being rejected, easier to handle. One respondent described being rejected through dating apps as ‘soft rejection’ and that many people may decide to use dating apps because it’s ‘sort of the path of least resistance’ (P1, age 23 years). Dating apps were also used for convenience, particularly for people in rural areas who may have limited options. One respondent described dating apps as providing ‘more options for dating and hooking up’ while also helping to create ‘some common ground before your first date’ to get to know another person (P2, age 60 years). Establishing this base connection was described as being particularly important for people in rural areas in order to save time and money when traveling to meet someone in an urban area.

Perceptions of dating apps and risk behavior: Respondents shared their perceptions of different dating apps. The main dating apps that were discussed include Grindr, Tinder, Scruff, and Growlr. Grindr and Tinder were mentioned the most and many respondents had similar perceptions of what each is typically used for. One respondent believed Grindr caters to a younger audience (P3, age 43 years). A common perception was that ‘Grindr and Scruff are more towards finding someone to hook up with’ and that ‘Tinder is most associated with trying to find someone to date (P8, age 23 years). One individual further explained his perceptions and how these perceptions may differ among gay and straight communities:

Grindr is, I perceive, as kind of dirty, slutty, uh, naughty, inappropriate, you know, it’s really for lewd hookup experiences I guess, um, … I definitely perceive it as being an application used for hooking up. I think that is also the equivalent of Tinder for straight people … And for gay people, I think Tinder is a lot more of a relationship-oriented application. The guys that I was speaking with on Tinder, were all really relationship oriented, from what I could tell, or that’s what they desired, not just a one-time thing. I mean I thought it was pretty successful. (P12, age 23 years)

The majority of apps among the MSM community are geared toward certain niches. One individual described Scruff as being for a ‘slightly older, more mature crowd’ and ‘a more hairy, muscular, bearded kind of guy’ and Growlr for a guy who is ‘a bit more heavyset, a little chubbier’ (P3, age 43 years).

Despite Grindr being the most frequently used app and the belief that ‘a lot of people are afraid of commitment – mostly men’ (P3, age 43), more than half of respondents (55%) reported that they were more interested in developing a relationship than just ‘hooking up’. Many men discussed wanting more of an emotional connection because the ‘thrill of just hooking up had faded’ (P5, age 27 years) and the idea of ‘hooking up’ with a stranger ‘provided too much psychological grief’ (P12, age 23 years) to deal with. One respondent explained that they would rather just be with one person who will ‘stimulate them intellectually and sexually’, particularly because ‘just hooking up’ puts ‘yourself at risk for contracting any number of [infections]’ (P16, age 27 years).

Technology’s role in health: Several interviewees (n=6, 30%) reported either using the internet to obtain health information or expressed support for integrating health information into apps. One respondent indicated that they receive nearly 95% of their sexual health information from the internet, partially due to the fear of verbally asking about sexual health information (P9, age 22 years). While sexual health information is available online, respondents commented that they wished ‘LGBT stats were more readily available on different platforms’ or that more general information on LGBT relationships and issues was in a centralized app or website (P17, age 21 years). Another respondent shared a similar perspective that ‘you can never put enough information out there’, but that ‘the focus is on HIV and leaves out a lot of other STDs [sexually transmitted diseases]’ (P18, age 52 years).

A few individuals specifically discussed sexual health information in relation to dating apps. One respondent (P9, age 22 years) mentioned seeing banners or pop-up ads talking about PrEP within the Scruff app. Another individual believed integrating PrEP messaging into dating apps could at least help to spark conversations surrounding positive sexual health (P20, age 40 years). Another participant shared their perspective:

I think technology has been good in that it does provide a venue for people a) to connect, and b) to be able to talk about things and maintain a certain level of privacy. It gives them an opportunity to … experiment with talking about sexual topics as well as romance … yeah, I would say that technology in general has been good for sexual identity development. (P6, age 36 years)

Based on these perspectives and because of their expansive usage, dating apps or other digital media could be a viable way to deliver sexual health information or prevention services to MSM in rural areas.

Summary of quantitative and qualitative findings

When considered together, the findings of this research suggest that dating app use is a frequent and accepted practice within the MSM community, particularly among those in rural areas. Apps are known to be associated with specific users or goals, such as ‘hooking up’ versus relationships, and individuals who use any of them have higher numbers of sexual partners compared to those who do not use apps. However, dating app users have more positive views of PrEP than non-users, and participants believed that apps could be valuable tools for sharing health information. Thus, while dating apps may lead to increased sexual risk, they also provide opportunities for disseminating HIV prevention information to rural MSM.

Discussion

The results of this mixed-methods study suggest that utilizing dating apps and mobile phones could be beneficial for making connections, creating a sense of community, and disseminating health information to MSM in rural areas. In this study, 73% of rural MSM reported ever creating a dating app profile and 72% of these individuals had an active profile. The majority of participants described their interest in seeking partnerships or more meaningful relationships, as opposed to just ‘hooking up’. Many survey participants met their current partner online and in qualitative interviews described how apps provide space for establishing mutual interests or understanding of intentions before meeting up with someone in person. One study found that MSM aged 18–24 years most frequently used dating apps and social media websites to make new friends, connect with existing friends, and meet new sexual partners23. This could indicate that MSM, particularly in rural areas, utilize apps to identify people close by that are similar to them and to feel more connected to their social networks.

In addition, participants discussed their perceptions of different dating apps. Some felt that certain dating apps were more for finding people to ‘hook up’ with, while others were more relationship-oriented. If health promotion practitioners hope to reach individuals who may be engaging in riskier sexual behaviors, it may be beneficial to target users of apps like Grindr, which was identified as having more of a ‘hook-up’ culture.

This research also examined the sexual behaviors of MSM who use dating apps and their attitudes and experience with PrEP. Current app users had more sexual partners than non-app users, but they also had a higher interest and more positive attitudes toward taking PrEP. This increase in sexual partners may explain the more positive attitudes toward PrEP, as the medication would be more useful to these individuals than to those who engage in less frequent sex. This is in line with previous research, which has found that Grindr users were more likely than non-users to engage in sexual risk behavior and to initiate PrEP treatment20. These findings point to the potential value of using dating apps as a medium for delivering PrEP education and messaging.

Several studies have examined the feasibility of promoting sexual health within dating apps and of providing online/mobile sexual health resources6,21,23. One study utilized Grindr to promote the ordering and use of HIV self-testing kits and found that Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM living in Los Angeles were highly interested in and accepting toward at-home testing21. Another study assessed the feasibility of utilizing an app for HIV prevention and found that most men liked the app and reported that they would use it again or recommend it to a friend6, while other research has found that rural MSM have positive attitudes toward technology-based health promotion interventions10. Utilizing apps to deliver services or HIV prevention information is cost effective and has the potential to be successful. These findings are particularly relevant for MSM living in rural areas because of the unique barriers to PrEP education and care that they experience8.

Limitations

Several factors limit the generalizability of this study. The survey data were self-reported and subject to recall bias. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits causal inferences from being made. Additionally, the sample was predominantly White and cis-gender men, reducing external validity. Participants were recruited using electronic means, which may have biased the sample toward more active technology users. Data were not collected on sexual orientations of survey participants, which may have limited the interpretation of the results. Lastly, the interviews provided a range of comprehensive information, but represented the experiences of a small group of MSM living in the rural South.

Conclusion

The current study examined the dating app use of MSM living in rural areas, their overall perceptions of these apps, and their sexual behaviors. The results of this study indicate that dating app use among rural MSM is prevalent for a variety of reasons, including to find meaningful relationships, to seek sexual partners, and to build social networks. Additionally, this study examined the attitudes of MSM in rural areas about using and accessing PrEP as HIV prevention. Based on these findings, dating apps may be an ideal venue for distributing PrEP information and education, given positive attitudes toward PrEP and low PrEP use and access among this population.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Department of Health Promotion and Behavior at the University of Georgia.