Introduction

Since the early 20th century, compulsory rural service has been a common strategy to mitigate limited healthcare access in low- and middle-income countries. In many low- and middle-income countries, governments employ ‘compulsory service with incentives’, in which clinicians’ education or licensure is contingent upon completion of rural service1. At least 19 Latin American countries have compulsory rural service programs for physicians1-4.

While much literature focuses on the effect of compulsory rural service on provider retention, little is known about its effects on healthcare providers’ professional development, particularly in Latin America5-7. A study in Ecuador from the 1980s suggests that physicians find rural service professionally and personally rewarding8. Guatemalan medical educators suggest that rural service enriched humanistic practice among dentistry students during the 1960s and 1970s, when the program began9. However, a recent review of rural medicine training programs in Central America highlights multiple challenges to trainees’ educational and professional experiences, including a dearth of professional role models in rural health as well as leadership and finance changes leading to poor program sustainability2.

Understanding how compulsory rural service contributes to healthcare providers’ professional development is of particular importance given the ongoing global health workforce shortage, which poses an important challenge to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of universal health care by 203010-12. Additionally, analyses of compulsory rural service provide insights into prioritizing development of human resource capacities to create equitable quality health care among vulnerable populations13. This qualitative study examines Guatemalan medical students’ experiences of rural service and the impact of rural service on their professional development.

Study setting

Guatemala is a Central American country of 15 million people where rural service is compulsory for skilled health professional trainees. While the constitution guarantees citizens free government-sponsored health care, health resource shortages commonly affect rural areas, where 46% of the population lives14. Most of Guatemala’s health infrastructure, including specialty hospitals and five medical schools, is concentrated in the capital city. While there are 26 skilled health workers per 10 000 population in urban areas of Guatemala, there are only 3 per 10 000 in rural areas. Indeed, Guatemala has the lowest availability of human resources for health in Central America. In 2014, the collapse of a primary care system designed to expand coverage in rural areas through non-governmental organization (NGO) contracting exacerbated the health workforce shortage and left four million rural Guatemalans without regular primary care15. Notably, indigenous Maya people, who constitute 42% of the population14, live predominantly in rural areas and were disproportionately affected15,16.

Since the 1960s, Guatemalan medical schools have required students to complete the ‘rural supervised professional exercise’ (ejercicio profesional supervisado rural, EPS rural) prior to graduation and licensing. Participation in rural service is a graduation requirement. Medical educators originally developed an 8-month rural rotation to teach medical students about social determinants of health9. Currently, the rotation lasts 4–6 months and is intended for medical students to synthesize clinical skills and serve rural communities17,18. During the rotation, medical students are assigned to a rural health post or clinic and function as primary care and/or basic obstetrics providers, depending on the location of their assignment. Students often work with community leaders and midwives in health promotion and education.

To date, the only scholarship describing rural service in Guatemala focuses on initiation of a dentistry student rotation from the 1960s to 1970s9.

Methods

Study design

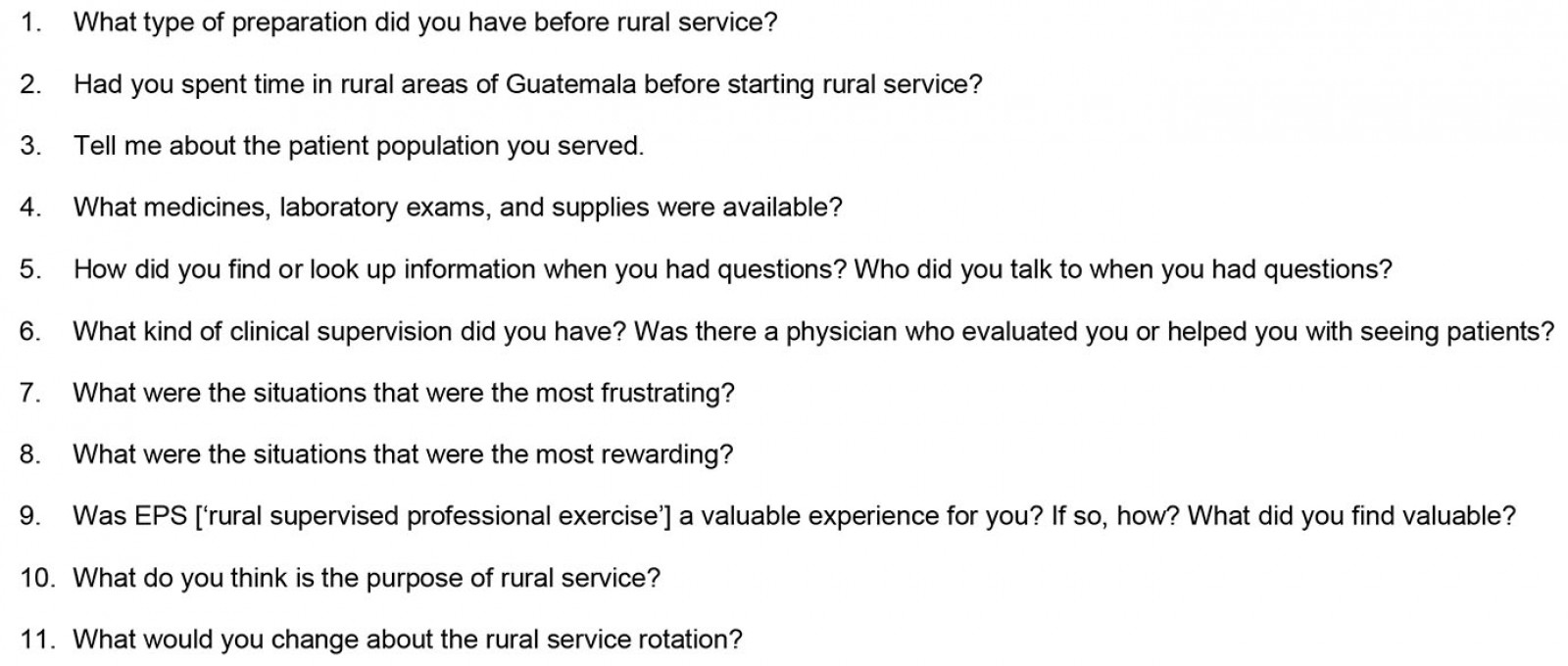

Guatemala-trained physicians who completed their compulsory rural service between 2012 and 2017 were recruited to participate in a qualitative interview-based study through chain referral sampling. Recruitment was limited to the two largest medical schools with the longest established rural service programs. The research team identified and contacted an initial set of eight participants through their own contacts developed through prior healthcare delivery initiatives in Guatemala. Subsequently, each interviewee was asked at the conclusion of the interview if they would be willing to provide referrals to current medical students and recent graduates who had completed rural service rotations from 2012 to 2017. Interviewees selected, from their contacts, individuals who met the inclusion criteria and then provided their contact information to the research team. Interviewees included students from Guatemala’s public medical school based in Guatemala City, the public medical school’s satellite sites based in western and eastern Guatemala, and Guatemala’s largest private medical school. Interviewees rotated in 11 of Guatemala’s 22 departments (Fig1).

Figure 1: Departments of Guatemala in which interviewees conducted compulsory rural service, 2012–2017.†

Figure 1: Departments of Guatemala in which interviewees conducted compulsory rural service, 2012–2017.†

Data collection

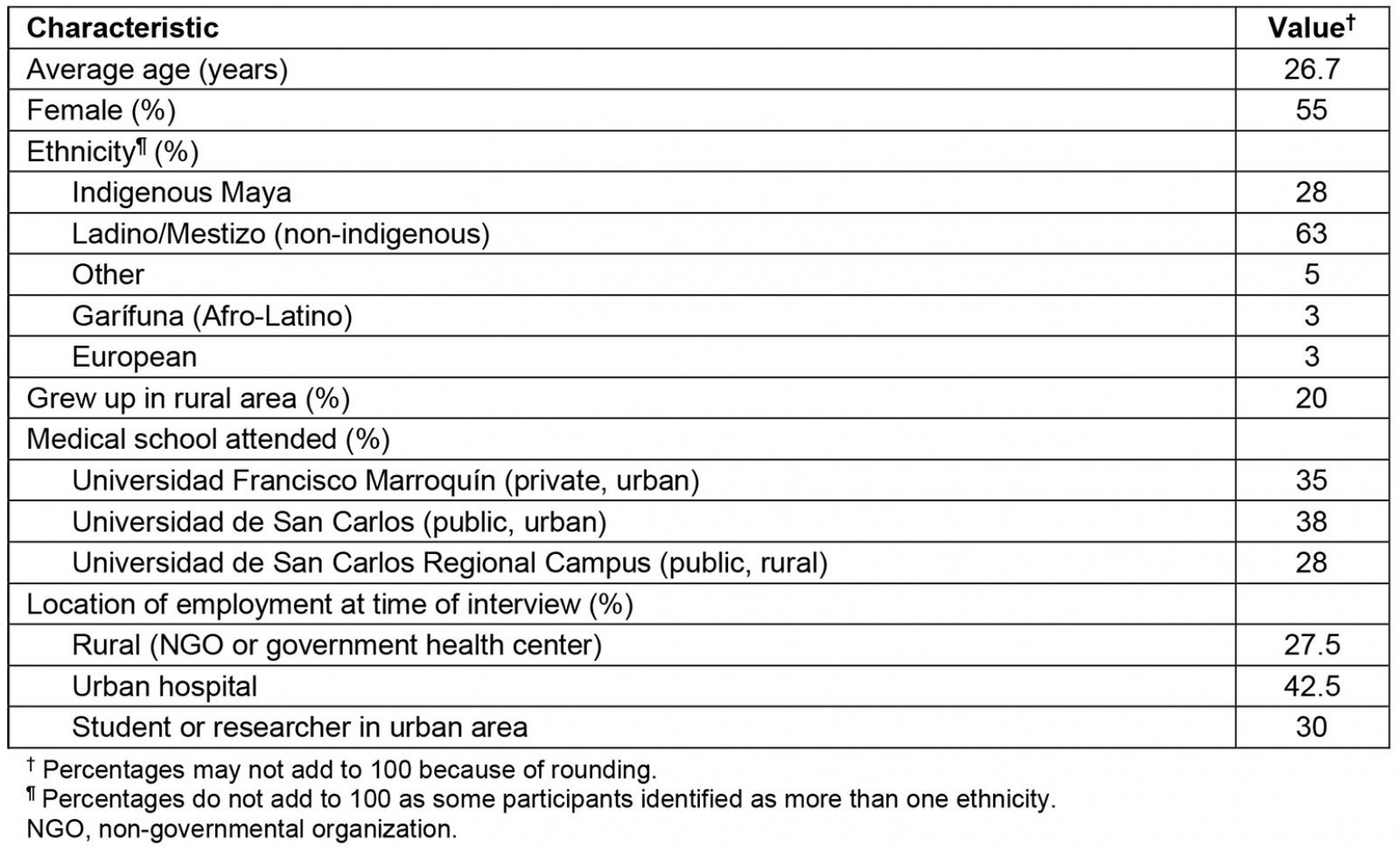

Forty semi-structured interviews lasting 30–90 minutes were conducted with senior medical students and recently graduated physicians in person or by phone. All interviews were conducted in Spanish by two interviewers (AC, JH) from January to May 2017. Interview questions focused on participants’ experiences of providing care, challenges and rewards, and perceived value of the rotation (Appendix I). Interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim by Spanish-speakers.

Data analysis

Qualitative data from interview transcripts were analyzed using an inductive approach, in which researchers review transcripts for repeated patterns of meaning and common ideas from study participants, also referred to as ‘dominant themes’19,20. First, the research team familiarized themselves with the data through review of transcripts from the first 10 interviews. Second, the research team met to discuss and develop categories characterizing broad domains of common participant experiences, such as ‘professional development’ and ‘challenges faced’. The research team developed and refined a codebook in successive rounds of transcript review. Each transcript was independently coded by two researchers, (ie the researcher tagged text relevant to each category of participant experience with its designated code). The research team subsequently resolved coding discrepancies and elucidated themes within each category of coded data by consensus discussions, using the qualitative data analysis program NVivo v11 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home).

Reflexivity within the research process

Qualitative research involves interpretation of participant experiences by researchers who have unique social positions and backgrounds. As such, complete objectivity in data analysis is not possible, but measures can be taken to encourage as broad and unbiased a view of data as possible. One such measure is engaging in reflexivity, the process through which researchers consider how their sociocultural values influence study design and analysis21. Another such measure is including a diversity of team members in the research team, including those with local experience, and obtaining feedback from relevant stakeholders. The team for the present study includes physicians from Guatemala [MC, BM] and the USA [AC, DF, KA], and social scientists from the United States [AC, JH]. All had previously conducted research on rural health in Guatemala. Team review of codes and themes facilitated maintaining local perspectives in data interpretation. Results were presented to health professionals and social scientists at five oral presentations in Guatemala and the USA for feedback on interpretation of the major themes identified. To protect participant identity, transcripts are not publicly available.

Ethics approval

This qualitative study was performed through Maya Health Alliance, an NGO providing rural health services in Guatemala. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Maya Health Alliance (2017-001) and Washington University in St Louis (201612017). All participants provided verbal informed consent. Research is reported following the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines22.

Results

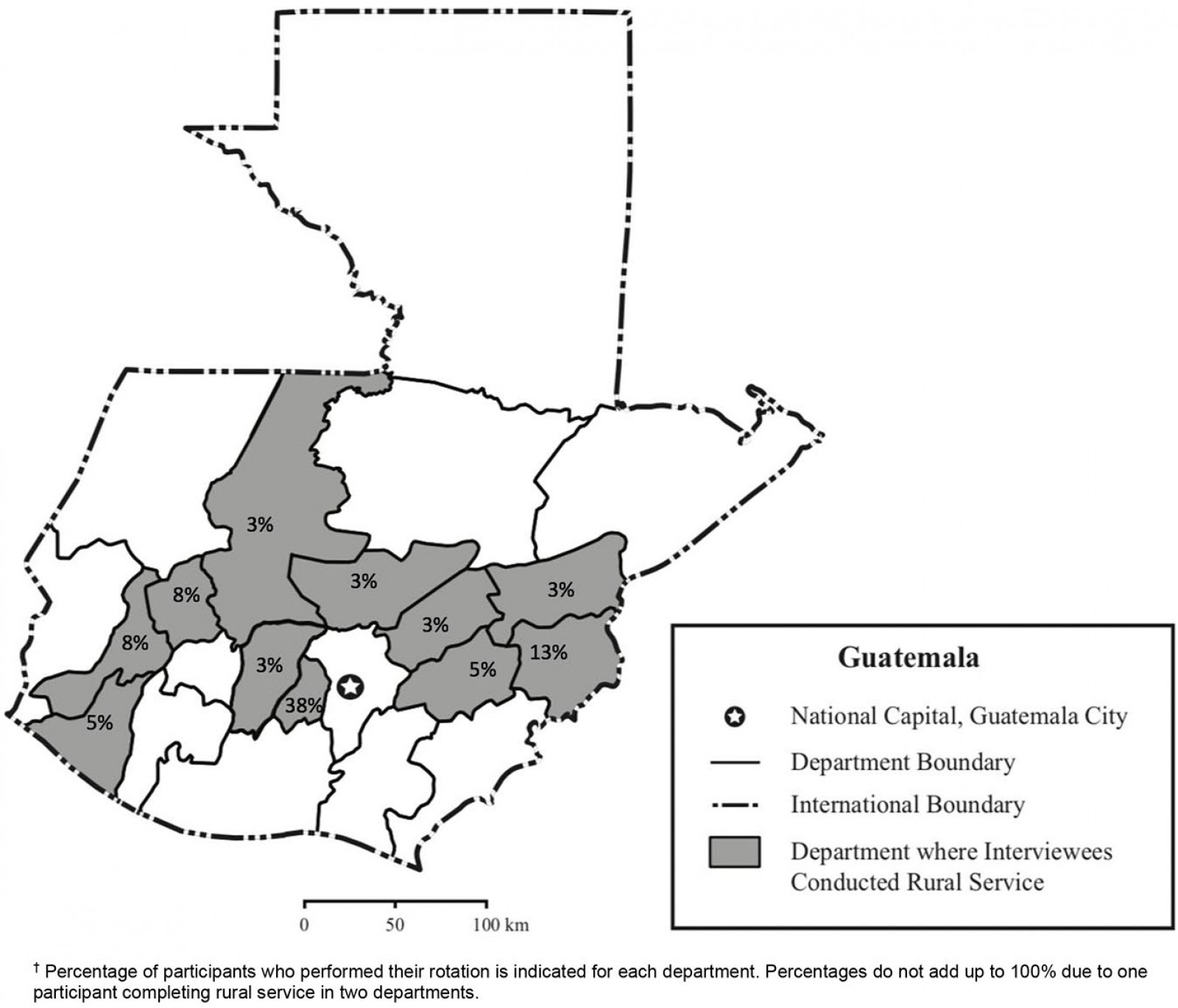

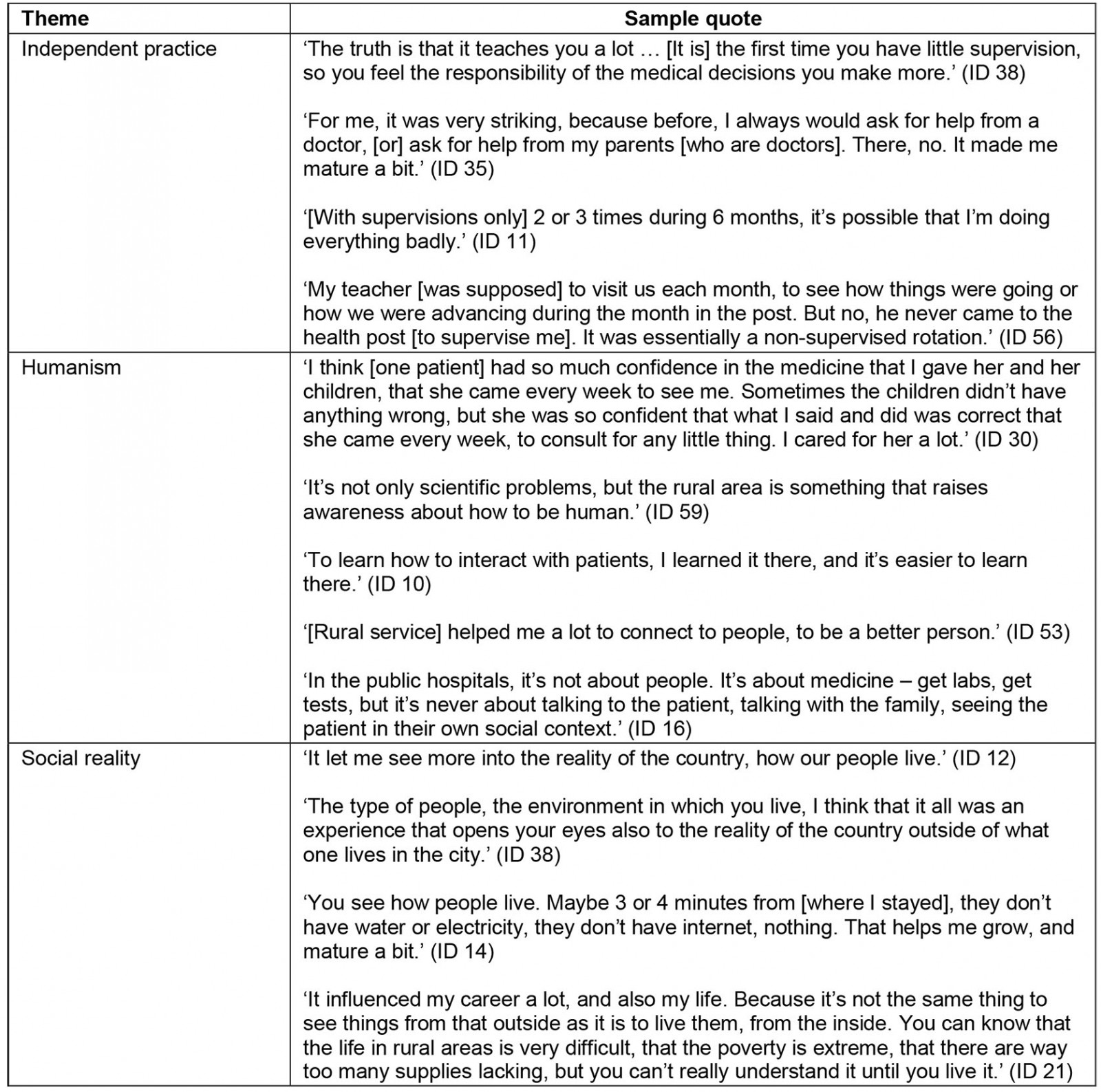

The majority of participants identified as non-indigenous (67%) and came from urban areas (80%); additional demographics are described in Table 1. Interviewees reported that rural service impacted physicians’ professional development with regard to independent practice (50%), humanism (58%), and sociopolitical awareness (75%). Sample quotes for each theme are provided in Table 2.

Table 1: Characteristics of interviewees (n=40)

Table 2: Representative quotes from interviewees

Cultivating independent practice

For most students, the rural rotation constituted their first out-of-hospital rotation and their first independent clinical experience. At the private medical school, students saw patients alone, but could discuss cases with faculty members on the premises during weekday business hours and by phone otherwise. Students from the public medical school saw patients independently and rarely had supervisors whom they could call to discuss cases. Supervisors performed on-site evaluations one to six times during the rotation. Students rotating in more remote health posts reported fewer visits than those near urban centers or in communities accessible by paved roads.

Half of interviewees reported that the rural rotation pushed them towards independent clinical decision-making and furthered their clinical skills. Some private school students described initial anxieties over attending deliveries and resuscitating neonates; students at both schools had initial doubts about their ability to provide appropriate care as a lone clinician for patients with complex medical conditions. Over time, students described feeling validated after making correct diagnoses and efficacious treatment plans. For example, some interviewees clinically diagnosed patients with congenital heart disease and cancer, and felt gratified when these diagnoses were confirmed with further testing and led to timely treatments. Students commented particularly on how clinical challenges contributed to their growth as clinicians, such as deciding when to refer a woman with postpartum hemorrhage or a child with severe malnutrition to a higher level of care. These situations helped medical students develop confidence in their abilities to practice independently:

[The rotation] is where you confirm to yourself that you are a doctor. And that you can make decisions based on the knowledge that you have acquired over the course of seven years. (ID 41)

It was the first time that I appreciated being a doctor. That I was alone on the service, and I had to make the decisions, as a doctor. (ID 46)

Independent practice also fostered students’ professional responsibility:

You learn more because you have to take responsibility for what you do. The patient is there, trusting in you. You have to do things well, because you are the responsible one. (ID 30)

Interviewees who did not feel that the rotation furthered their independent clinical decision-making had engaged in prior out-of-hospital rotations or rural medical volunteer work, or planned to pursue surgical or hospital-based specialties after graduating from medical school and did not find primary care-related decision-making relevant to their future careers.

While students appreciated cultivating clinical autonomy during rural rotations, the majority of interviewees viewed clinical supervision as infrequent and inadequate. Similar proportions of interviewees described this problem at the private and public medical schools. The majority of interviewees from the public medical school reported that supervisor visits centered on logistical management instead of clinical decision-making:

Clinically, supervision was very poor. It was supervision more to make sure that I was going to the school to give health education … But, I didn’t have clinical supervision that would evaluate if I could diagnose a pneumonia, for example. (ID 35)

How we were doing with the organization of the medications, how we were managing the medical attention, and how you were managing the registry of vaccinations of the community – that was what they supervised. (ID 8)

Interviewees from the private medical school reported receiving feedback from faculty about clinical knowledge based on written tests and group presentations, rather than clinical precepting.

Overall, students’ frustrations with infrequent supervision reflected an underlying sentiment that greater access to clinical resources could improve their autonomy and patient safety. While some had access to basic textbooks and Ministry of Health protocols, others had no clinical resources on site. A minority of interviewees reported using cell phones when confronted with a clinically challenging case to access online repositories about clinical management guidelines or reach other students, medical residents, or physician relatives for advice.

Understanding the sociopolitical reality of rural Guatemala

The majority of interviewees felt rural service helped them ‘understand the reality of our country’. Participants used this phrase to refer to social determinants of health such as poverty, limited access to transportation, and poor sanitation infrastructure. Participants from urban areas reflected on the differences between their living conditions and those of their patients:

We live in a bubble in the city, where we all have access to electricity, where the needs are totally different. When you’re exposed to this, for many people, it’s the first contact with that side of Guatemala. (ID 5)

I think that it’s important that doctors have contact with the people that are from rural areas of Guatemala. Because there is a reality in the country that we don’t know. And it’s important that doctors know how people live. (ID 40)

They also reported that rural service gave them insights into patients’ delayed care-seeking and cultivated sympathy regarding patients’ inabilities to purchase medications or travel to referral hospitals. For example, one interviewee described ‘putting herself in the shoes’ of her patients: ‘As a human being, it opens your eyes to the people … you’re not going to buy medicine if you don’t have enough to buy food’ (ID 31). Students described how these situations impacted them professionally and personally:

I never understood that for some people to be able to get to a health center, or post, they had to walk 3 or 4 hours. Because there was no other form of transport. That they didn’t even have 5 quetzales [Guatemalan currency, equivalent to $0.65] to leave [home], and be able to buy a bag of water. That you understand when you see it close-up. Not only did my professional life change, but it all changed. You learn to see life in a different way. (ID 21)

Notably, even the minority who grew up in rural areas or identified as indigenous Maya emphasized that rural service showed their peers the reality of the country:

I think you realize the reality of the country when you come to [rural service]. Well, all of my life, I’ve had to live this, and [the other medical students] only when they come to [rural service]. (ID 36)

Students described exposure to rural areas as crucial to developing sociopolitical awareness about their patients’ lives and basic needs:

If you were not there as the doctor, there wouldn’t be anyone else. You are providing a lot to the community, where there aren’t many services. The purpose of us, as doctors, is just that. That we develop a social conscience, and know that we are always going to come in contact with that kind of person that needs your help. (ID 2)

Developing humanism in medicine

Over half of interviewees emphasized that rural service fostered humanistic medical practice. As one student reported, ‘It’s something essential that you learn – not necessarily medicine, because that you learn reading, or in classes. But it’s more how to treat people’ (ID 31). Others similarly contrasted the scientific and humanistic aspects of medicine. Interviewees reported approaching patients in rural practice more holistically, attending to patients’ social needs and context:

[In rural service], you learn not only about diseases, but the integrated person. To see the patient as a person – part of a society, a family. It’s not like you’re just seeing the disease … You learn not only to see the sick person, but you learn about how to attend to the whole person. (ID 6)

Similarly, another interviewee described developing an understanding that patients often presented with somatic complaints but wished to discuss difficult household dynamics or mental health. She discussed rural service as a time where she could consider patients as human beings, rather than focus on pathophysiology alone: ‘You know what most gratified me? It was to be able to listen to them, because they are so used to doctors doing everything to them mechanically’ (ID 11).

Interviewees also developed skills in building rapport and found gratification in establishing relationships with patients that superseded cultural and class differences. For example, one medical student recounted developing a trusting relationship with a pregnant woman who had a low amniotic fluid index. Initially, the patient declined a hospital referral due in part to community-wide fear and mistrust of the hospital. Over multiple conversations, the student convinced the woman to accept the referral. During a newborn checkup, the patient revealed that she had named her baby after the medical student: ‘The mom said, 'If it weren’t for you, the doctor, my baby would not be here'. And I think that was the most gratifying thing’ (ID 3). Another student described the experience of learning to offer biomedical treatments to patients who preferred local ethnomedical treatments:

That is something the doctor can accomplish if you have their trust. You can’t make a face when the patient says that they were using [herbal remedies]. So, if you don’t say anything and then later you explain, then they accept the treatment. But it’s a lot about trust, and not saying anything [negative] at first. (ID 17)

Another interviewee reported gratification that, despite differences in class and ethnicity, she was able to establish trusting relationships with her patients over time:

The patients began to have trust in me, and they did not just see me as a doctor, but as someone they could talk to … It was very difficult for them to have this trust in me, due to culture, you see? Like that, a beautiful relationship grew. (ID 57)

Due to their experiences with independent practice, sociopolitical awareness, and humanism, the majority of interviewees reported their experience working in rural areas as rewarding and felt rural service should be mandatory.

Discussion

This qualitative study describes Guatemalan medical students’ perceptions of how compulsory rural service affects their professional development. Major themes emerged about challenges in supervision and access to educational resources as well as positive values placed on developing independent practice, sociopolitical awareness, and humanism. These findings have important implications for improving professional opportunities and offering more equitable health services.

Interviewees’ concerns about poor supervision merit attention. Problems with inadequate orientation and supervision during rural rotations have similarly been documented in other Latin American countries2,8,23. One study in Mexico demonstrated that over 30% of students performed rural service independently despite lacking professional competencies24. Medical students’ limited preparation and resources to deliver primary and obstetric care can adversely affect healthcare quality for those living in rural areas, as suggested in a recent health system assessment of Guatemala and a study of compulsory rural service in Ecuador15,25.

In Central America, it is well documented that changes in financing as well as government and educational leadership compromise regular supervision and longitudinal faculty mentoring in rural rotations2. This challenge reflects a broader history of health system underfunding in the region, driven in part by public health investment restrictions imposed by structural adjustment policies and regional and global lending agencies. Within Guatemala, limited public health funding is applied towards pressing population health issues, such as vaccination efforts and maternal-child health, rather than to medical training26. Multi-sector collaborations offer a potential solution to the underfunding of teaching and mentoring within rural service programs. Clinical preceptors and tutors can play an important role in helping students with clinical decision-making to deliver appropriate care, understanding how to maneuver health system resources, and in processing and debriefing in challenging cases. In one innovative model in Chiapas, Mexico, the NGO Partners in Health collaborated with Ministry of Health clinics to offer increased supervision, mentorship, and clinical resources to rotating physicians27. Given robust NGO involvement in rural health care within Guatemala16, such a model could be replicated. However, long-term financing models must be developed to ensure sustainability2,28. Additionally, as telehealth and mobile phone infrastructure expand in Latin America29,30 utilizing telemedicine for supervision and providing app-based education to rural rotators offer feasible and advisable options. In Guatemala, studies of tele-consulting and app-based referral platforms for community health workers in rural areas have shown promise31,32.

Interviewees’ concerns about poor access to clinical education resources must also be addressed. Electronic-course, internet, and digital library-based distance learning opportunities have been successfully implemented in general medical training and education in other low- and middle-income countries33. While information technology infrastructure varies by medical school and area of the country, when electronic devices and internet connections can be made available, students in rural health rotations can benefit from digitized, open-access medical courses that offer independent learning modules34,35. For areas with minimal internet or cellular reception, clinical texts and protocols can be digitized and made downloadable and accessible on devices offline. Orientation to the rural service rotation could also include making students aware of free online and evidence-based clinical decision-support resources, such as Medscape.com, and of services that offer complimentary subscriptions to those serving vulnerable populations, such as UpToDate.com.

Despite the important concerns interviewees raised about their rural service experiences, the present study suggests that rural service helps medical trainees develop self-confidence in clinical decision-making as well as a sense of responsibility towards patients. As such, this study echoes findings from studies in Ecuador(8} and South Africa36. Compulsory rural service may also play a role in promoting equitable and respectful health care among health professionals. Participants in this study perceived that rural service deepened their abilities to form doctor–patient relationships, including across cultural differences; they also reported increased awareness of sociopolitical determinants of health with exposure to patients’ difficult living conditions. Developing these capacities is particularly important for healthcare professionals in Guatemala, where rural and indigenous patients commonly perceive discrimination in medical facilities37,38. Literature suggests that rural service sensitizes physicians to local needs, barriers to care, and social determinants of health in Mexico2, Costa Rica2, Ecuador8, and Cuba39.

Public health leaders in Guatemala have expressed concerns that graduating physicians receive limited education on social determinants of health15. The present study points to rural service as a natural opportunity for structured clinical education about this topic. The collaborative program in Chiapas described above, which includes seminars on social determinants of health, offers a promising model27. Similarly, rural health education for medical trainees in Costa Rica in the 1970s involved a course about socioeconomic determinants of health called ‘The National Reality’ in striking parallel to language used by the present study participants28. Scholars of medical education suggest that such courses, which tend to occur only during rural service, should ideally occur longitudinally over the course of professional training2. However, adequate financing and human resources are paramount to sustainably offer such curricula.

Findings about the role of rural service in cultivating sociopolitcal awareness point to rural service as a potentially transformative learning experience, one that can generate change agents who use their experiences to modify health systems to meet local needs35. However, the effect of such sensitization on physicians’ long-term practice and individual patient interactions is poorly understood. Furthermore, it is unclear if developing sociopolitical awareness is associated with retention of healthcare workers in rural areas – a complex problem. In a study of a Chilean rural service program, the majority of participating physicians reported they would return to their rural service location after completing their obligation, due in part to value placed on social relationships developed during their experience40. However, a recent systematic review of rural health workforce retention strategies found that regulatory measures to attract healthcare workers to rural areas, such as compulsory service, did not translate to workforce retention41.

Limitations

This study faces five major limitations. First, chain referral sampling was initiated through contacts engaged in rural work. This methodology was critical to gain participants’ trust before asking personal and potentially emotionally fraught questions. This strategy biased the sample towards those with a commitment to rural health care and potentially more favorable opinions about rural work, though most were not working in rural areas at the time of interview. Second, participants may have had recall bias as they were interviewed up to 5 years after completion of their rural service rotation. Third, the sample was recruited from two of the five medical schools of Guatemala. The three medical schools not represented in our sample are private institutions that charge significantly higher tuition rates than the public medical school, with more urban, non-indigenous, and higher economic status student demographics than those represented in the present sample of public medical school participants. As such, the findings may not be generalizable to all trainees. Fourth, this study focused on students’ perceptions, rather than those of medical educators or patients. Fifth, the authors are unable to provide data about whether and how rural service has affected participants’ behaviors and medical practice since graduation, which is an important direction for future study.

Conclusion

Guatemalan medical students perceived that compulsory rural service contributed to their professional development by building their clinical autonomy, fostering their humanistic abilities, and increasing social awareness. As compulsory rural service continues in Guatemala, improvements in access to clinical resources and supervision are needed. Exposure to rural practice inculcates in trainees an appreciation for social determinants of health, a human resource capacity necessary for equitable primary healthcare delivery to marginalized communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joaquin Barnoya and Pablo Garcia. AC receives support from the Houston VA Health Services Research and Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (CIN13-413).