Introduction

The majority of the 9 million people in Papua New Guinea (PNG) live in rural areas1. Mortality rates for infants and for children under five are high, and under-five mortality is 20% greater in rural than in urban areas2. Pneumonia is the leading cause of infant and child deaths3. Rural health services are provided by community health workers (CHWs) with 2-year certificates, nursing officers (NO) with 3-year diplomas, and health extension officers (HEOs) with 4-year diplomas or bachelor level of pre-service training. These healthcare workers (HCWs) often work in under-resourced and remote health facilities in which good performance goes unrewarded.

To reach WHO’s Sustainable Development Goals, investment in and support of the rural health workforce is essential. Meeting and surpassing the Department of Health minimum standards4 is necessary and issues adversely affecting rural health workers’ performance must be addressed5.

The introduction of an improved oxygen delivery system using oxygen concentrators and pulse oximetry has been shown to reduce mortality in hospitalised children with pneumonia in PNG by 35%6, but many rural health facilities have had no electricity supply. Between 2014 and 2016 a program funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and other partners installed solar power units and oxygen concentrators in 30 rural health facilities, and oxygen concentrators were provided to eight facilities with line power. An implementation effectiveness trial of the use of solar power to drive oxygen concentrators was established in 2017, involving a before-and-after evaluation with continuous quality improvement and a health systems approach7. Paediatricians and the principal investigator (FP) carried out training on clinical guidelines, oxygen therapy and equipment after installation and regularly thereafter. Improved clinical outcomes have been reported8. This study explored views of HCWs on program outcomes for themselves and their communities.

Methods

Study design and participants

A pre-tested, self-reported survey using open questions was carried out among HCWs in 38 rural health facilities. All HCWs available on the first day of the visit were invited to take part.

Questions sought information about participants’ experience of having power and oxygen concentrators available.

Procedure and measurements

The study was carried out 3 years post-installation. FP spent 3 days in each of the 38 health facilities. After the study purpose was explained, the HCWs available on the first day of the visit to each centre were given the questionnaire, which was collected on day 3.

Thematic analysis

An anchor code guided the selection of relevant comments from each participant’s responses. Codes were then selected and sorted into categories, with specific concepts referencing to the codes identified. Unifying themes were then derived.

Ethics approval

This study was part of a broader effectiveness field trial. Ethics clearance was obtained from the Medical Research Advisory Committee (MRAC No. 18.12) and School of Medicine and Health Sciences Research and Ethics Committee, University of Papua New Guinea.

Results

Ninety six of the 100 questionnaires were returned (two from medical officers, 19 from HEOs, 51 from NOs and 24 from CHWs).

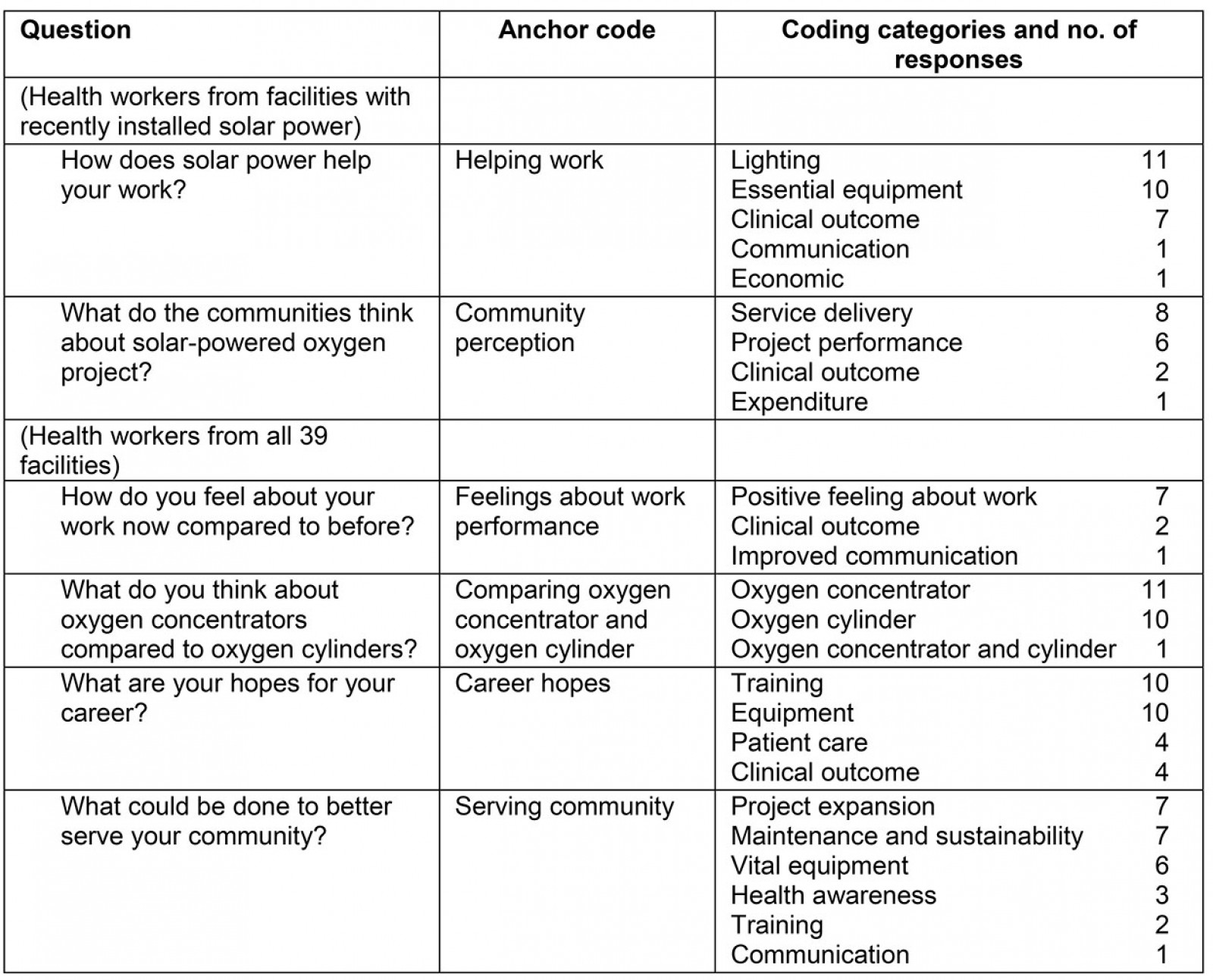

Table 1 shows the questions, anchor codes and number of codes in each category. Emergent themes are as follows.

Improvements

Improved service delivery: The program had benefits far wider than the use of the oxygen concentrator. Improved lighting enabling safe and efficient work in the labour ward and operating theatres, and the ability to use power-dependent equipment and maintain the vaccine cold chain figured prominently in responses.

Lighting helped me a lot in the initial management of oxygen for the pneumonia children and also for the continuation of treatment. Not only that, it also provided light in the labour ward. … (NO, Yampu Health Centre)

Improved clinical outcome: Participants took pride in improved clinical outcomes resulting from fewer referrals and lower mortality.

I felt that using oxygen concentrator today has reduced much of the workloads and also saved many lives of children including neonates and infants who required oxygen. (HEO, Sigmil Health Centre)

Solar power is an excellent project which helped a lot in saving the lives of many children between 0–5 years of age. (NO, Ialibu Health Centre)

Improved staff performance: Participants felt their work had improved and was easier, safer and faster, resulting in improved morale and job satisfaction.

We struggled so much in doing deliveries at night because we were using torch or lamp … work has become more easy and many helpless lives were saved. (NO, Gumine Health Centre)

The project has boosted staff morale in providing quality health care. (CHW, Pangia Health Centre)

Oxygen concentrator is far too good, special thanks to whoever created that handy machine. I used to carry that heavy cylinder from ward to ward before, but now is easy to carry or push. (CHW, Kaupena Health Centre)

Improved communication: The use of solar power to charge mobile phones improved communication.

The solar power helped us in charging phone in communication, typing and reporting, using suction and nebulizer machine, and using lights during delivery and emergencies. (NO, Nondugl Health Centre)

Reduction of costs of patient care: Respondents noted that the provision of reliable solar power reduced the costs of fuel for generators and the need for referring patients to larger health facilities.

Solar power made the health centre benefit very much by providing lighting and oxygen via oxygen concentrator to severe pneumonia cases. This saves cost of buying fuel and cost of referring the patients to the hospital. (NO, Det Health Centre)

Positive community perception: Participants reported that the community appreciated that the program had improved outcomes, with fewer referrals and better access and service delivery.

The communities have expressed good feelings and satisfaction because more children were treated and saved. (HEO, Det Health Centre)

Sustaining impact

Respondents recognised that several requirements were necessary to sustain the positive impact of the program.

Training: Respondents expressed the need for ongoing training, recognising that upgrading clinical skills and knowledge improves capability, capacity, productivity and performance.

My hope is that officers should undergo training for the usage and maintaining of the solar powered oxygen system. (NO, Goglme Health Centre)

Project extension and expansion: Participants felt that the program should be extended to the outpatient, emergency room, adult wards, offices and staff houses, as well as expanding to other rural health facilities.

We need more oxygen concentrators for other wards too, especially medical, surgical and obstetrics and gynaecology. (HEO, Chuave Health Centre)

Project maintenance for sustainability: The need for equipment maintenance was frequently expressed. The health workers recognised their responsibility to look after the equipment and use it correctly.

The solar powered oxygen project is indeed helping the community and it is now our turn to look after the project [solar and concentrator], and use it wisely so that it can last long and benefit the community. (NO, Kagua Health Centre)

New equipment installation: Participants highlighted equipment required to improve preventative and curative health services, including a vaccine fridge and overhead light for suturing.

Health awareness: Participants recognised the need to work with the community to improve awareness of common illnesses and their prevention.

Table 1: Study questions and coding strategy

Discussion

Responses were overwhelmingly positive. The only problem with the solar power system (raised by four respondents) was running out of the battery power backup after poor weather.

Hypoxaemia is a major cause of mortality in acute lower respiratory infection in children in low–middle income countries9. The introduction of oxygen concentrators has improved outcomes in remote settings10. Study participants reported improved outcomes in their own facilities.

Appropriate infrastructure, adequate resources, career development and continuing education have been identified as motivational factors in improving staff morale5. The provision of a reliable power supply was highly valued by the study participants and its use extended well beyond the prime aim of the project. Improved lighting was a vast improvement on the use of torches and mobile phone lights. Water could be pumped to the labour wards, nebulisers, suction machines and laboratory equipment functioned, and computers and printers were used.

Well planned and supported programs involving interaction with and training of health workers have a major effect on job satisfaction. The ability to charge mobile phones improved communication. Work was easier, more efficient and effective, and morale had improved, with reduced mortality and fewer referrals to the district hospitals. Communities had a positive perception about the program. Community support positively influences PNG rural health workers’ motivation11.

Participants recognised that maintaining the success of the program would require regular refresher courses and maintenance of equipment, and the importance of taking ownership with local health authorities and communities.

The wish for self-improvement through continuing education – an almost invariable finding in studies of motivation12,13 – is often overlooked by health planners. Continuing education is important not only for self-esteem but also improves care for patients and communities.

Study limitations

The investigator’s presence may have introduced positive bias. Some responses indicated incomplete understanding of the questions.

Conclusion

Health workers acknowledged the program’s positive effects on work performance, patient care and clinical outcomes. They recognised the need to take ownership of the project and stressed the need for continuing education and support. The views of rural health workers should be an integral component of efforts to improve health services.

References

You might also be interested in:

2019 - Strategic analysis of interventions to reduce physician shortages in rural regions

2013 - The role of risk theory in rural maternity services planning