Introduction

Community health workers (CHWs) are an important mechanism for connecting patients with health service organizations. CHWs have served as a vital resource for improving the accessibility and reach of health care in hard-to-reach communities worldwide. Evidence has consistently shown how CHWs can improve healthcare access and outcomes, strengthen healthcare teams, and enhance the quality of life for people in underserved communities1. CHWs also play an essential role in delivering culturally sensitive health services to diverse communities2. However, CHWs face numerous social and cultural challenges that influence the quality and accessibility of their services. These challenges depend on the sociocultural milieu of the region and country in which they reside. There is a need for research that examines these challenges for the purposes of formulating interventions designed at reducing their impact on the quality and accessibility of community health care. For example, a synthesis of systematic reviews on CHW programs found that community embeddedness, defined by the authors as community members having a sense of ownership and positive relationships with CHWs, was among the most important factors that contribute to CHW success3. However, community embeddedness is wrought with numerous challenges rooted in the sociocultural and economic contexts of regions and countries. Scott and colleagues (2018) suggested the need to develop tailored evidence that appropriately informs policy and practice that reflects regional and cultural differences3.

This article focuses on South Asia, which consists of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. While there are thousands of distinct cultures and ethnicities in the region, South Asians can be considered a pan-ethnic group with similar characteristics and a shared history that has contributed to South Asia’s present-day social, cultural, and political environments. In South Asia, CHWs have played important roles in health promotion, pregnancy, delivery (childbirth), and family planning services. Recent estimates show that for every 1000 residents, India has 0.6 CHWs, Pakistan has 0.5 CHWs, and Bangladesh has 0.1 CHWs4. Unfortunately, CHWs face numerous challenges that complicate the quality and accessibility of the health services they provide. Many of these challenges are social, cultural, or political in nature, and there have been few attempts to investigate these influences. As such, this article examines the social and cultural challenges that CHWs face in South Asia that complicate the quality and accessibility of health services they provide. This article will not only analyze potential barriers to practice and cultural acceptance, but also outline the strategies implemented to address, alleviate, or modify these challenges. To the authors’ knowledge, there is no published literature that has systematically and comprehensively categorized the social and cultural influences that CHWs face in South Asia, while there has been a sizable amount of research in this area. By better understanding the role of CHWs in South Asia, more can be learnt about specific strategies that promote CHWs across a milieu of social, cultural, and political considerations. This insight would enable the formulation of tailored guidance on the design, administration, and monitoring of CHWs in the region.

Methods

Eligibility

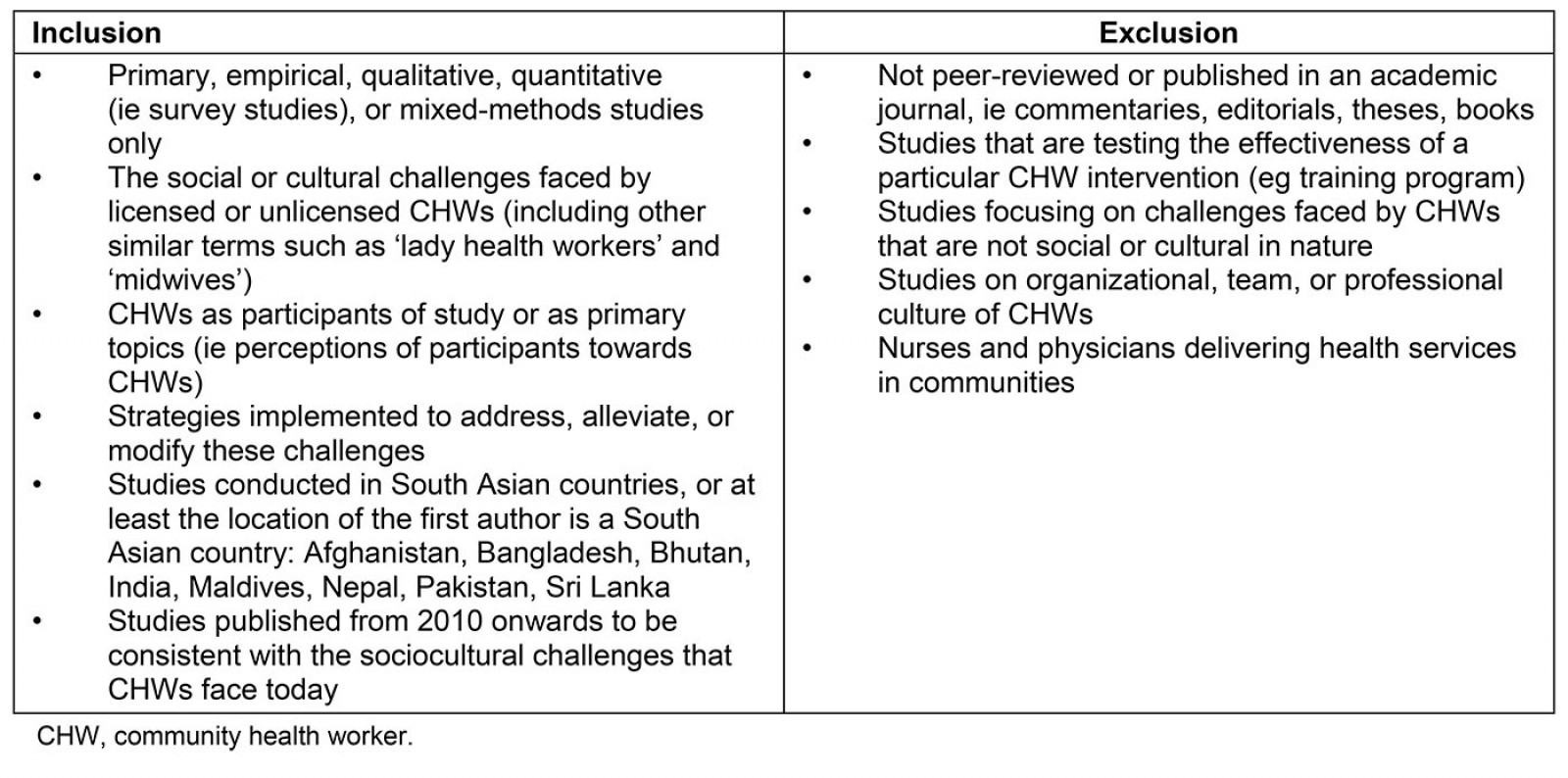

This study was most interested in primary empirical articles of any study design that discussed the cultural and social challenges faced by CHWs in South Asia. CHWs were defined broadly as those who work as licensed or unlicensed healthcare workers in South Asian communities. CHWs included ‘lady health workers’ and traditional birth attendants, but not midwives or nurses unless their role was primarily situated in a community context. This study looked for studies where CHWs served as participants and described the challenges they faced, or where the authors analyzed the patients’ and people’s perspectives of CHWs in their communities. The full list of eligibility criteria is shown in Table 1.

Search strategy and screening

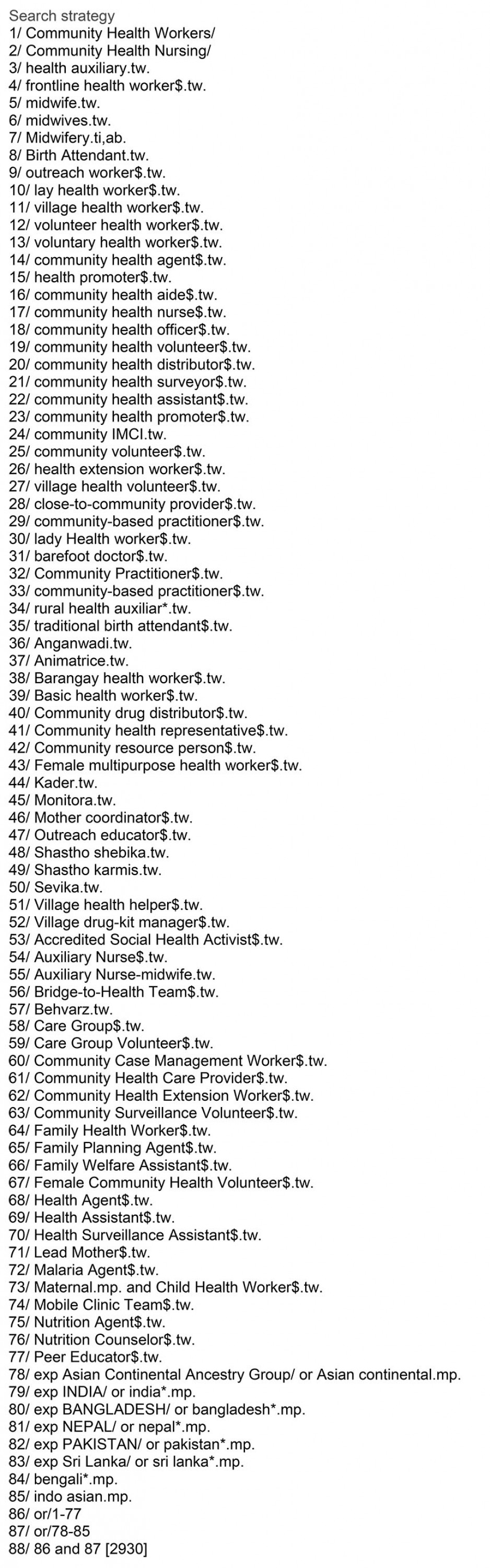

A systematic database search was conducted on 29 January 2020 in MEDLINE, Embase, Global Health, and PsychINFO. The search strategy was developed iteratively by using previously published reviews on CHWs and discussion among the research team. The research team conducted both title and abstract and full-text screening in pairs with verification using the Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation; http://www.covidence.org), a review screening software available online through institutional access. All conflicts were resolved by a third screener at both stages.

Data extraction and analysis

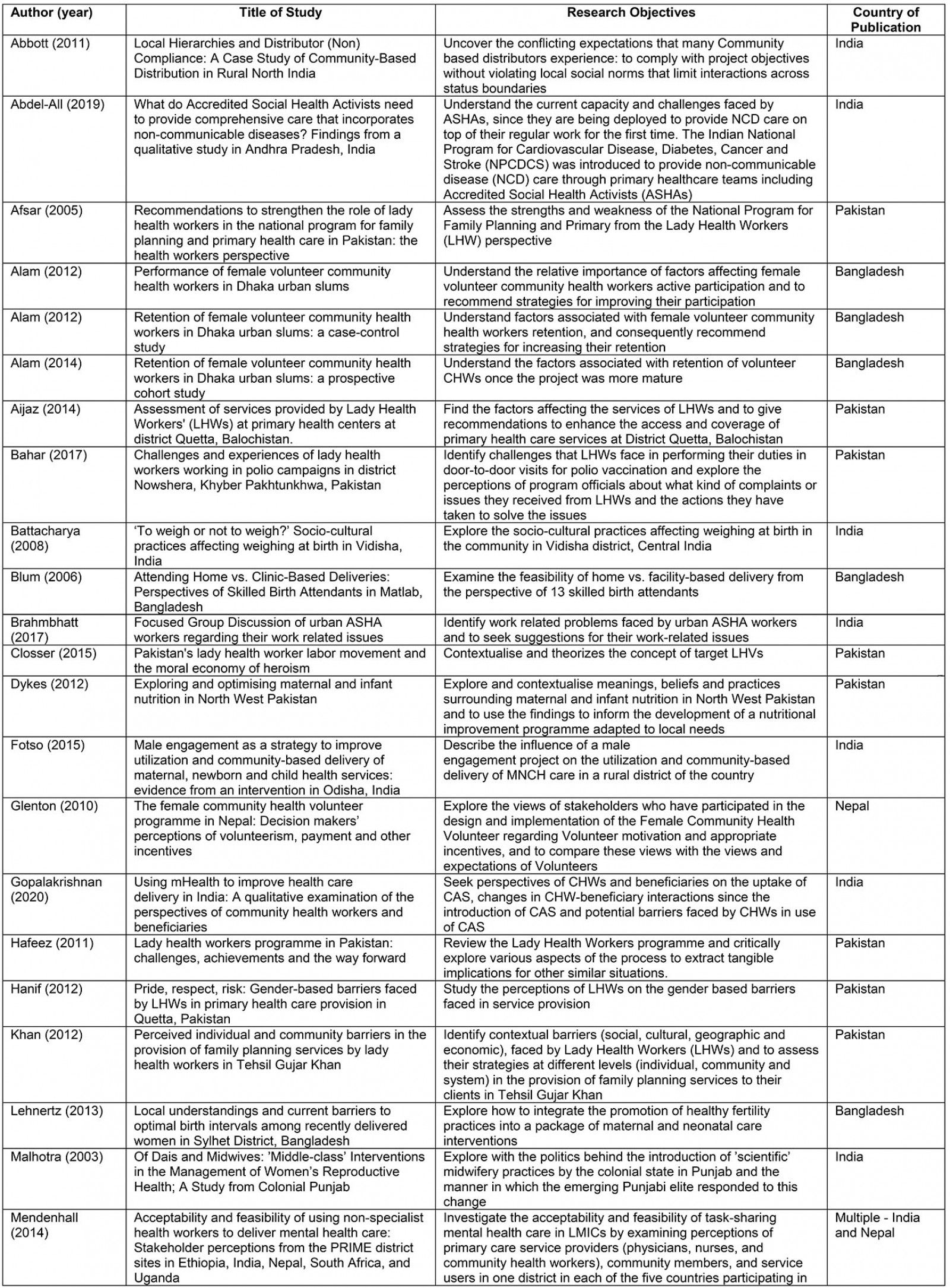

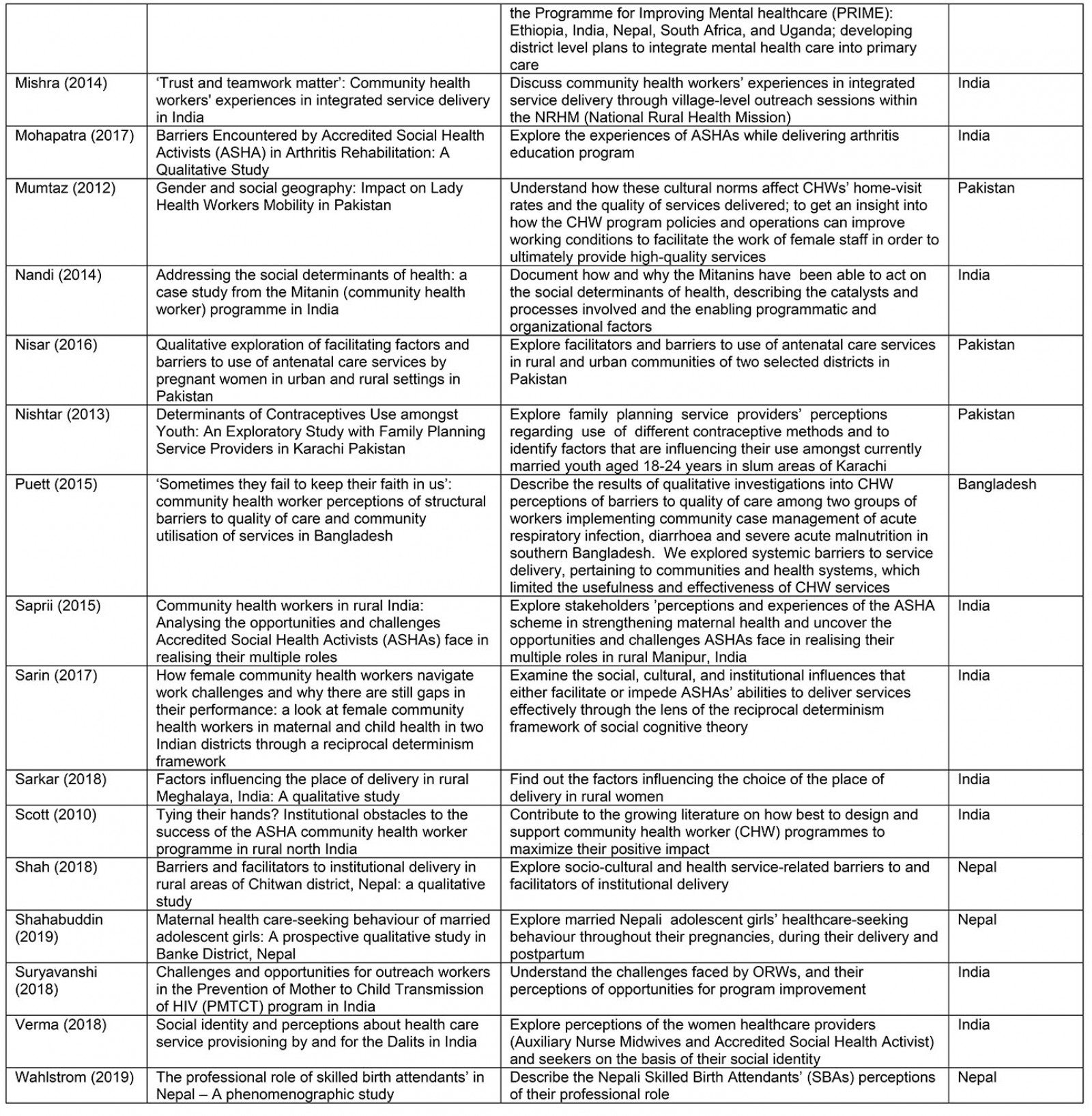

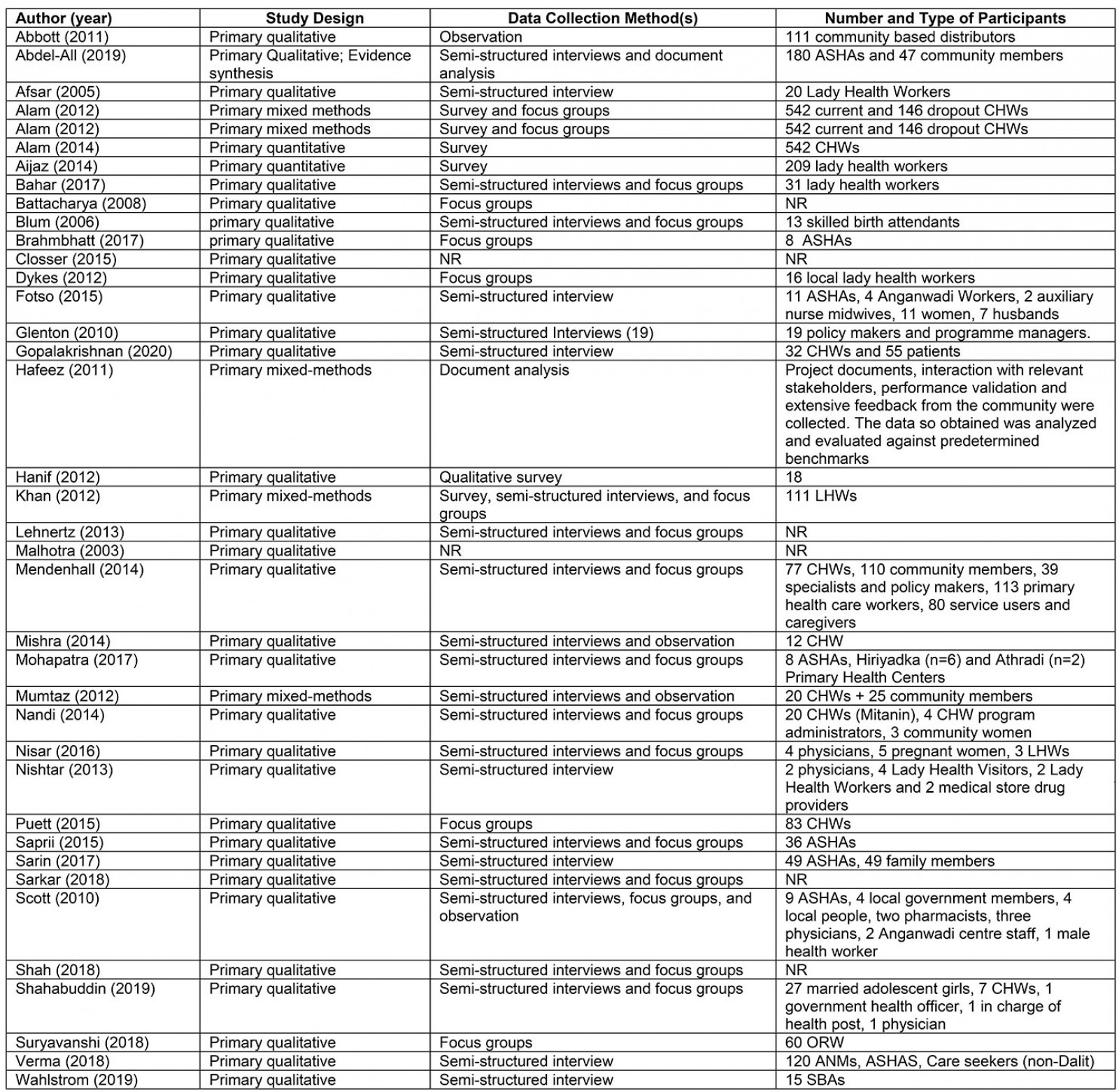

The following study and participant characteristics were extracted from included studies: author, year of publication, title of study, research objectives, country, study design, data collection methods, and number and type of participants. The descriptive analysis and the descriptions of each study can be found in Appendix I.

This study employed thematic analysis and constant comparison to categorize the findings of all studies5. All researchers first read through the same five articles and developed an analytic memo indicating their findings in relation to the research questions. The research team then discussed their reflections and developed a taxonomy of themes and subthemes. This taxonomy served as a guide for a second round of pilot coding where another set of five articles was reviewed as a team and the preliminary taxonomy of themes and subthemes was refined. Once the team was comfortable with the taxonomy, they analyzed the remaining articles in pairs, iteratively refining the taxonomy with emergent themes, subthemes, and concepts. Once all articles were coded, each researcher developed a narrative summary of the themes. The lead researcher reviewed these summaries and integrated them into a findings section. All researchers then reviewed the findings section to ensure its accuracy and comprehensiveness.

Table 1: Eligibility criteria

Results

Search results

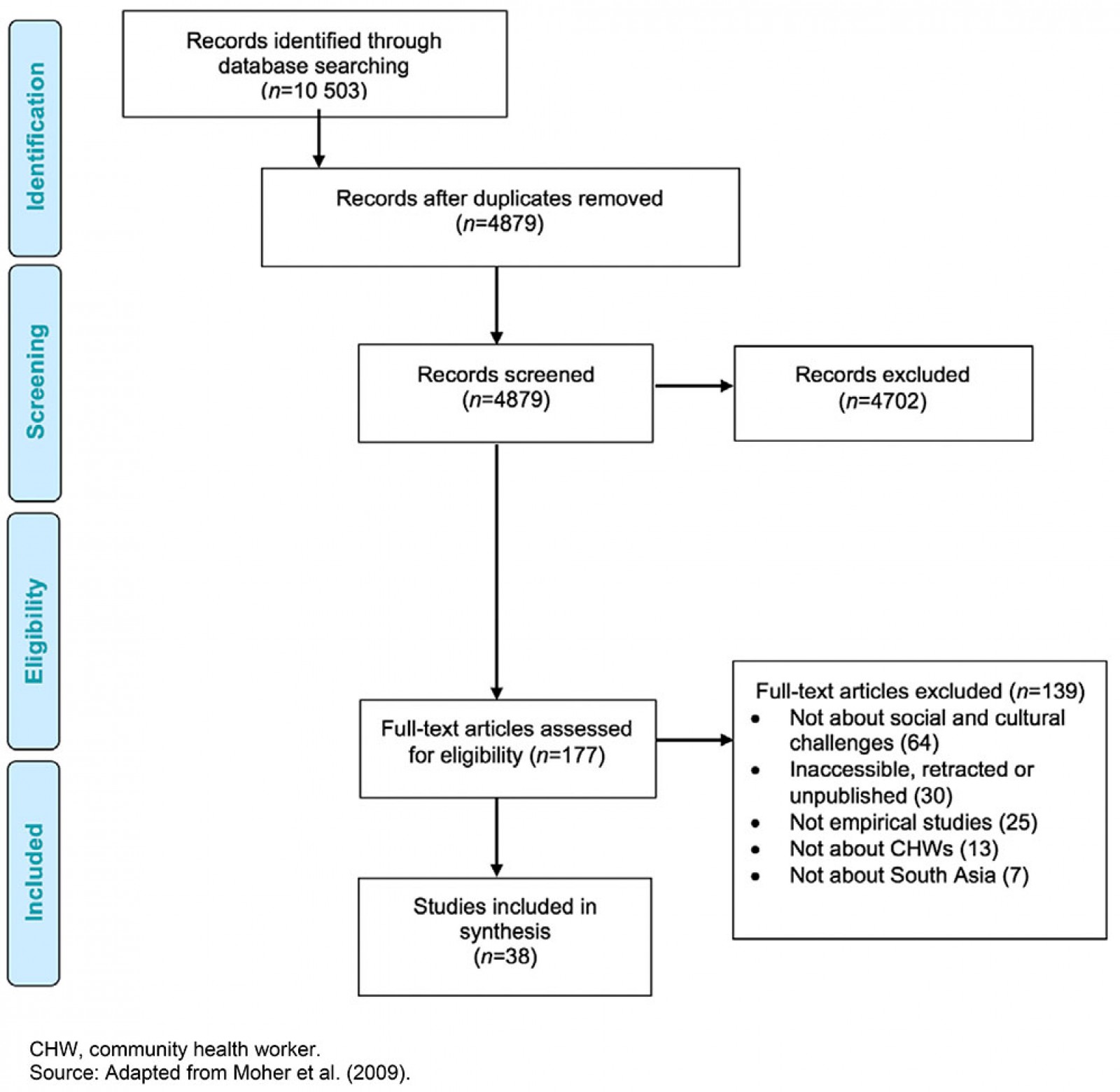

After the removal of 5624 duplicates, title and abstract screening was performed on 4879 articles; 4702 were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. Full-text screening was conducted on 177 articles and a further 139 studies were excluded for the various reasons outlined in Figure 1. A total of 38 studies were analyzed in this review6-43.

Figure 1: Screening and selection

Figure 1: Screening and selection

Religious and cultural norms

Out of 38 articles, 16 articles mentioned religious and cultural norms as they pertained to CHWs. In this section, these issues are highlighted.

Disrespect, disapproval, and physical challenges: CHWs faced disrespect from the communities they served, which was often rooted in cultural norms pertaining to the role of young females in families and communities. For example, in one study in Pakistan, young unmarried CHWs expressed how their community viewed them as ‘immoral women’ because of their interactions with men, which conflicted with cultural norms that circumscribed male–female interactions in the community23. Specifically, unmarried females were required to sit with men and discuss health topics, such as sexual health, as part of their CHW responsibilities; these discussions were considered to be taboo. CHWs reported a number of challenges when trying to discuss family planning with men; these challenges were pronounced when receiving training by male staff on how to have family planning discussions because of cultural norms that guide male–female interactions23. In some cases, interactions between unmarried CHWs and males in the community over time led to CHWs being considered by the community as ‘unmarriageable’. To prevent negative cultural attitudes towards them, CHWs refrained from carrying materials with the CHW program logo to avoid association with disseminating contraceptives and ‘spreading immortality’. Similarly, Bahar and colleagues noted how CHWs had to manage Pakistani community misperceptions about polio vaccines13. Cultural mores and norms led to negative attitudes that ultimately limited the quality and reach of their health services in the community10.

Blum et al detailed how religious beliefs and practices in Bangladesh moderated the relationship between CHWs and the communities they serve15. The authors explained how the birthing environment in traditional Hindu households – a temporary, separate room referred to as aus ghor – was particularly problematic. Typically, the room barely had adequate space for the mother and baby, forcing the CHW to position herself partially outside the structure when assisting the delivery. Furthermore, the CHW was unprotected from rain during monsoon seasons. Additionally, due to the association of blood and fluids with pollution, the structure was typically constructed in a ‘dirty’ area. Communities also subscribed to choa-chuee, a belief system that anything an ‘impure’ person touches is also impure, and therefore must be avoided. As a result, during delivery, family members would refuse to provide assistance or materials to the CHW because they were regarded as ‘impure’. Furthermore, the CHWs were required to pump the tube well for water herself, or somebody from the family would pour water into her cupped hands, invariably maintaining a distance while doing so. These practices caused frustration for CHWs, who expected and appreciated cooperation during the birthing process.

CHWs reported how cultural norms impeded their ability to provide care to women in their communities. For example, Blum et al noted that in Bangladeshi village settings, families typically allocated a dirty, private corner of the house to serve as a place for delivery15. In addition, as families placed a strong emphasis on removing women from the prey of evil spirits, a dark area was preferred. The lighting was generally poor, as most rural households did not have electricity. When the delivery occurred at night, there was only the light from a kerosene lamp, which was insufficient, especially if an episiotomy was needed. Delivery bed materials had to be discarded after the birth because childbirth was traditionally considered to be polluted by low-caste community members. Hence, an old blanket or jute sack was placed on the floor, covered by a plastic sheet. CHWs found it arduous to deliver on the floor, which they felt compromised their skills.

Gopalakrishnan et al also noted a number of sociocultural barriers in India that were alleviated by digital health interventions21. Specifically, CHWs noted that sociocultural and gender norms prevented young newly married women from stepping out of their home or being seen in public, which limited the CHWs’ ability to provide them services by mobile health. In certain cases, cultural norms also restricted women from leaving their homes after giving birth for more than a month after delivery, which prevented women from accessing essential postnatal health services.

CHWs reported cultural and religious norms that inhibited their clients’ freedom to make decisions about their health, which made it difficult for CHWs to carry out work such as linking women with antenatal care and institutional delivery36. CHWs reported difficulty in registering women early in their pregnancy partly because of cultural norms that preferred sons over daughters. Couples with a female child were reluctant to disclose second pregnancies because of taboos around expectations of a male child. Verma and Acharya also detailed that CHWs in India did not hold any power to influence community social structures, even if they wanted to, because they feared retribution by community members42. In particular, these CHWs were restricted from visiting the houses of lower-caste clients and were bound to visit affluent houses because of their influence and resources within the community.

Cultural perceptions of family planning and contraceptives: Some CHWs highlighted that the health services they provided, such as family planning, were perceived negatively by community members. For example, Khan et al described how a Muslim community in Pakistan held the perception that family planning was a ‘sin’ against Islamic principles and promoted a Western agenda to control the population of low-income countries24. However, Baha et al noted that in some Pakistani Muslim communities, religious leaders would publicly preach the importance of CHWs, which contributed to community acceptance of CHW health services13.

Cultural preference for home delivery: CHWs reported how cultural and religious norms contributed to women preferring home delivery rather than institutional delivery. For example, Blum et al noted that CHWs in Bangladesh were expected to deliver at home, regardless of their client’s condition15. Similarly, Sarin and Lunsford detailed that there were strong cultural preferences in India for home deliveries, coupled with religious proscriptions against immunization, birth spacing, and contraception36. Additionally, cultural, and religious norms also affected CHWs’ self-efficacy; CHWs had to convince women to use health services, and often cultural norms in Nepal inhibited women’s agency in making decisions about their own health36. Shah et al also noted that sociocultural norms affected women’s choice to deliver institutionally, specifying that women chose traditional care during birth and the postpartum period where they received support from their family and neighbors, and chose to deliver in a healthcare facility only if there were complications39.

Personal biases of CHWs: Some articles reported that CHWs displayed bias stemming from their own cultural and religious beliefs, which affected the quality of care they provided. The following biases were found to be particularly important: between Hindus and Muslims, between higher and lower castes, and between older and younger generations. First, Sarin and Lunsford reported how, in India, CHWs’ beliefs affected how they treated their clients36. For example, Hindu CHWs refused to enter or eat or drink at the homes of their Muslim clients, which limited interactions, decreased the quality and reach of their health services, reinforced stereotypes, and impeded the promotion of birth spacing methods. Additionally, CHWs in India displayed their biases by showing a tacit preference for sons being born36. As a result, clients refrained from disclosing a second pregnancy because of community expectations of a male child.

Second, Abbott and Luke noted that the quality of care provided by CHWs in India correlated with the client’s caste6. For example, one CHW was noted to approach the homes of her upper-caste clients and often accepted a seat on one of the charpoys (woven cots) in front of their houses, expressing familiarity with them through gestures and physical cues. Meanwhile, the same CHW would remain standing at the perimeter of the cluster of lower-caste houses while speaking with her clients, often using a harsher and more instructional tone of voice. Lower-caste women were also observed to be apprehensive of the CHWs, suggesting that they were unaccustomed to such visits and had not developed a rapport.

Finally, Abbott and Luke also described how the age of the CHWs in India contributed to low-quality health care6. Specifically, the CHW they interviewed enjoyed a high status within the family and community as a married woman with sons. The CHW followed a set of norms regarding how she could interact with girls and women of lower generational status. For example, it was considered taboo for parents to talk to their children about sexuality. When asked why sisters-in-law were allowed to talk to adolescents about sex but mothers were not, the CHW answered: ‘Mothers consider themselves to be an elder of the family and they feel embarrassed talking about these things’, thus contributing to the lack of awareness of sexual health among youth. Additionally, in one study from Pakistan, CHW perspectives on contraceptive use among youth emphasized a lack of awareness about important contraceptive issues, as well as a lack of understanding of contraception33. Therefore, religious and sociocultural beliefs about different contraceptive methods among CHWs could be potential determinants of low contraceptive use33.

Cultural and religious practices and misconceptions: Some CHWs discussed the intersection between cultural practices and health, specifically when it related to women’s health. For example, Dykes et al described how women in Pakistan may be given local herb solutions over what is recommended by allopathic medicine for breastfeeding18. Similarly, Bhattacharya et al highlighted that CHWs in India who delivered neonates tended to avoid cutting the umbilical cord because of a sociocultural stigma that cutting the cord is considered impure or polluting, irrespective of their formal training14. Religious practices also seeped into maternal health care. For example, Bhattacharya et al noted that some Hindu communities believed in sutak (ie pollution confinement), where the mothers and neonates were considered unclean or polluted and therefore were socially and physically segregated from the community. The authors compared this with a similar practice of ritual baths that occurs in the Muslim faith.

It was also noted that the community’s overall lack of information, compounded by cultural and religious beliefs, led to misconceptions about maternal and child health care. For example, Bhattacharya et al reported that there was a lack of knowledge in India about the importance of birth weight, with a higher prevalence of home births leading to reduced opportunities of weighing newborns at birth14. There was an additional layer of superstition and belief that knowing the birth weight led to the child’s sickness through the ‘evil eye’. However, the authors reported no apparent familial resistance towards recording birth weight and that men were more likely to support this practice.

Gender and sex

Thirteen studies discussed barriers related to the gender and sex of CHWs6,10,11,15-19,23,24,31,35,36. Challenges associated with gender and sex included difficulty balancing work with family and home-life expectations, barriers specific to being a female worker, barriers to working with female clients, and security concerns. Specifically, Khan et al speaks to the ‘lack of education, excessive domestic work, family pressure, husband resistance and limited mobility’ as being gender- and sex-related challenges for CHWs in Pakistan24.

Managing domestic and CHW responsibilities: Difficulty balancing professional work with personal lives and children was a recurring theme across the literature17. Because of societal norms and cultural expectations, women often lived within extended family systems and had significant household responsibilities that posed a challenge to pursuing a career as a CHW18. CHWs also reported that their CHW responsibilities had a persistent impact on their ability to fulfill their domestic, household responsibilities, leading to family disapproval over time23. Dykes et al outlined further challenges associated with women and the reality of their home life as ‘although they prepare meals, male and elderly members of the household eat first and women last. This means that in a culture where, due to poverty, most people’s diet is already suboptimal, women are likely to receive an even poorer nutrient intake’18. Alam et al highlighted that 11% of female CHWs in their study in Bangladesh left their work because of disapproval from their husbands or families, speaking further to the challenge gender plays not only in the work of CHWs in South Asia, but also in their retainment11.

Household responsibilities were culturally considered to be the reponsibility of females even if they were working as CHWs, so maintaining a work–life balance was challenging without family support10. CHW retention rates were heavily affected by these household expectations10. In addition, lack of family support or disapproval from family increased dropout from the CHW program, and contributed to demotivation for those CHWs who remained10. However, while many CHWs in this study reported that they struggled to manage both expected household responsibilities and CHW duties, the majority expressed confidence in their ability to manage both10.

Gender- and sex-related barriers when interacting with clients and community members: In addition to facing disapproval at home, female CHWs faced challenging interactions with clients because of their gender and sex35. Hanif and colleagues highlighted that unmarried female CHWs in Pakistan faced greater behavioral restrictions than married women faced around men, which created barriers to providing health services that adequately addressed their clients’ needs23. Female CHWs also shared being alienated from decision-making in their communities and being unable to attend village meetings because of their sex31,35.

A case study in Northern India discussed a specific challenge faced by women in health care called purdah. Purdah is ‘a cultural institution that strictly regulates interactions between men and women, especially married women, to protect the honor of the family’6. Due to purdah, female CHWs were limited in the interactions they could have with men outside their homes, which led them to refrain from providing health education to men on taboo topics such as contraception6. Although purdah’s intent is to ‘protect the status of a woman’, it impeded CHWs’ ability to provide information, education, and communication to the community on various health topics, all rooted in their sex and/or gender. Efforts to transform the strict norms of purdah, enforced by the communities, were also resisted by communities6.

Not only did gender and sex pose a challenge for female workers interacting with male clients, but the same challenge was faced if their clients were female. Women tended to react in a different manner when their husbands were home, changing the dynamic and limiting topics and questions they felt comfortable discussing or inquiring about23. Generally, in certain cultures in South Asia, men were viewed as the gatekeepers of women receiving care; so, CHWs who felt uncomfortable with their interactions with men would in turn have trouble providing health services23. Additionally, when it came to topics specifically related to family planning, women would often have to ask their husbands’ permission, thus making it difficult for CHWs to promote family planning in various communities24. Because of this notion of men being gatekeepers of women, CHWs found it best to advise women who approached them for contraceptives to first speak with their husbands to avoid conflict36.

Security and safety concerns: Many female CHWs living alone in the communities they served feared being harassed by men16. They also found it dangerous to travel alone at night; for example, to deliver medication and resources to clients19. Within clients’ homes, CHWs experienced disrespect and even abuse from men23. These security challenges faced by CHWs translated to poor health outcomes and even mortality of their clients. For example, one CHW feared that they would be kidnapped in the community, and therefore decided against seeing a client, which resulted in the client’s death15.

Caste

Seven included studies discussed the barriers that CHWs faced related to caste and status in communities6,7,14,15,17,28,42. The role of caste in South Asia is all-pervasive, touching all aspects of life, and this has implications for CHWs. Despite an intention to minimize the social distance between the CHWs and lower-caste clients, class hierarchies were reinforced by the way CHWs provided their services and communicated with community members6. Such power dynamics were evident when the quality, tone, and extent of interactions between CHWs and clients depended on the caste of both6,28. These power structures were also accepted, and potentially upheld, by some lower-caste women, making it difficult for CHWs to reach all populations6. For example, conflicts or tensions arising from caste differences led to diminished communication and provision of inadequate healthcare information and services6. Some care seekers reported that they were asked for their caste when they visited healthcare facilities, with the quality of their treatment depending on the answer42.

According to one study, the roles assigned to CHWs were based on their social status, which was partly determined by caste differences14. CHWs of lower castes, including Dais (ie traditional birth attendants in rural India), had different roles and responsibilities than those of higher castes42. Traditionally seen as the serving class, Dalits (ie the lowest caste in India, deemed the ‘untouchables’) were often met with societal resistance if they sought to increase their status and reputation42. Some care seekers may also hold biases against Dalit CHWs42. For example, clients in one study generally maintained their identity when interacting with CHWs, even if this meant that higher-caste patients refused or belittled care from lower-caste CHWs42. As a result, CHW autonomy may be circumscribed by a social obligation that emphasizes prioritizing service provision to the higher-caste elite42. For example, communities often viewed midwifery as ‘polluting’ or impure work42. For this reason, Dais were often expected to dispose of the placenta and bathe ‘polluted’ newborns. This expectation stemmed from the belief of pollution confinement, where Dais interacted with the mother and neonate because Dais were already considered ‘polluted’ due to their lower caste14. This expectation was reinforced in CHW training schemes that taught an array of skills according to caste, where more ‘polluting’ work was allocated to lower-caste CHWs14.

Caste-based discrimination was also seen in care provided by CHWs of higher castes42. For example, higher-caste CHWs demanded greater respect from lower-caste clients42. At the same time, some CHWs from higher castes showed disrespect to clients and their families of lower castes15. In fact, some upper-caste CHWs scolded and humiliated clients in an attempt to reinforce their ‘higher caste’15. Some CHWs also disrespected or harassed lower-caste clients because of a perceived lack of competency7. Other CHWs refrained from entering the houses of lower-caste clients42. This reinforced a tacit conflict between local norms of segregation by caste – both spatial and social – and CHW duties42.

Generation

Four studies identified that CHWs in South Asia faced unique generational barriers, which often intersected with other structural challenges6,23,36,39. Status and interpersonal relationships were generally governed by generational hierarchies, where older generations were typically responsible for decision-making that affected all family members6,36. For example, some elder family members, such as mothers-in-law, advanced their cultural preferences for home deliveries; in many cases, this was coupled with a religious proscription against immunization, birth spacing, and contraception36. The dominance of elder family members in decision-making served as a common challenge for CHWs in carrying out health promotion activities36.

Other forms of social stigma related to generational differences existed when CHWs interacted with children and adolescents. Health promotion efforts were affected by taboos that meant refraining from discussing sexuality with children6. The social rules that prevented parents from engaging in such discussions with their children determined which health information was delivered and how, which hindered CHWs’ abilities to carry out professional responsibilities6. Although trained to provide health care to adolescents, some CHWs limited their interactions and educational efforts with younger clients, to maintain their clients’ perceived purity and innocence6.

One study found that a generational hierarchy existed in societies where decision-making was dominated by men39. Social norms and the patriarchal power structures in Nepal pressured women into a more passive decision-making role39. In India, a woman’s status was often associated with her age, marital status, and if she bore sons or daughters6. This translated to the unique struggles of female CHWs where young female workers faced greater behavioral restrictions around men, such as limited direct interaction if at all, while older and married women did not face the same barriers23.

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this systematic review of 38 studies, it was found that CHWs face a number of sociocultural challenges when working in South Asian communities, including religious and cultural norms and practices, gender and biological sex, caste, and generation. Although an attempt has been made to outline how each type of challenge differs, the authors would like to emphasize the interconnectedness of the challenges. All challenges in some way relate to one another and stem from the unique sociocultural milieu of South Asia, and the various subcultures that exist in this diverse region. The findings of this investigation may serve as an essential resource for program planners and decision-makers considering how to improve the effectiveness and reach of CHW programs. The following section will continue the examination of these challenges in light of extant literature.

Importance of considering the sociocultural milieu

It was found that the sociocultural milieu of South Asian communities has unique effects on the attitudes, behaviors, and practices of community members, which ultimately affects CHWs’ scope of practice. The professional autonomy of CHWs is important to consider because it can contribute to high-quality and immediate health care for rural and remote communities where health care is inaccessible. For example, a number of studies have promoted the notion of expanding CHW scope of practice as important CHW competencies44,45. In this view, the CHW scope of practice is not rigid, but is evolving and expanding with time to create CHWs who have the skills to provide an array of health services that meet the needs of their communities. However, the value and belief systems present in South Asian communities permeate in a variety of ways that can both promote and circumscribe the capabilities of CHWs to provide high-quality, immediate, and accessible health care.

In this review of primary studies, multiple instances were found where barriers stemming from the caste, age, or biological sex of CHWs led to low-quality care or the death of patients in emergency care situations. These barriers reflect long-standing community perceptions towards a group of people and their characteristics. These perceptions can have long-lasting impacts on CHWs, which ultimately affect healthcare access in rural and remote communities where CHWs provide most of their services. The sociocultural milieu where CHWs work has seldom been considered46, at least compared to program and financial considerations1,9. Negative community perceptions may be difficult to tackle or reduce once they have taken root in community value systems. Community perceptions of CHWs are also essential to consider because, as has been shown in this review, they have unique impacts on the daily lives of CHWs beyond their professional roles and responsibilities. For example, because CHWs were tasked with educating men on taboo topics, some communities considered them unmarriageable because of the purdah value system23. Furthermore, CHWs who primarily provided birthing services were permanently associated with pollution confinement because of the perception that birthing and delivery is a ‘dirty’ process15.

Overall, a number of self-reinforcing characteristics were found that contributed to the further stigmatization and marginalization of minority communities. Lower-caste CHWs, for example, were more likely to provide care to lower-caste clients and be tasked with specific activities – such as birthing – that contributed to negative community perceptions of them. This example emphasizes how the sociocultural milieu affects the lives of CHWs in ways that serve to compound this misfortune, depending on the social locations of CHWs in their communities. This is in line with other literature on this topic; a comprehensive review of CHWs found that although CHWs provide essential health care, they are viewed as ‘second-class, temporary solutions’47. In this current investigation, the various self-reinforcing characteristics have been elaborated on. The multiple barriers that circumscribe the role of CHWs in rural and remote communities, that limit the extent to which they can provide high-quality and accessible care, have been described. The authors believe that the value and belief systems of South Asian communities often become among the biggest implementation barriers for meeting the goals intended by CHW deployment in rural communities. It is essential to prepare current and new CHWs in South Asia to identify and address priority challenges that arise from their community’s unique sociocultural milieu48. This skill will aid in creating deeper and more positive relationships with communities and other healthcare providers, which will ultimately contribute to a higher quality and access of care.

Conclusion

These findings recommend that CHW programs incorporate tailored and specific cultural learning as a core component of CHW practice. Cultural learning has been identified by previous research as an important program component; but there is still a need to introduce greater opportunities to receive relevant and tailored learning to the unique sociocultural characteristics of communities45,49. Certain characteristics of cultural learning are essential. First, it is important for CHW programs to explicitly recognize the importance of the effect of cultural values and beliefs on CHW practice. This recognition entails preparing CHWs to build a positive rapport with community members as well as explaining to CHWs that their rapport with their community will have long-lasting impacts on their lives beyond their work as a CHW.

Second, it is important for CHW program planners to recognize that CHWs are members of communities they serve, so they may hold and express the same values. This may introduce challenges to their professional responsibilities. This study found multiple biases in CHWs that circumscribed the equitable provision of health services in communities: between religions, between castes, and between generations. Although there is a considerable amount of guidance on developing CHW programs50, little tailored guidance was found on preparing CHWs for some of these sociocultural realities.

Finally, CHWs work in intricate and fragmented healthcare systems that require frequent cooperation with community leaders and healthcare providers. Developing positive community and healthcare provider perceptions of CHWs is essential. Some research from the USA shows that healthcare providers with greater cultural competency were more likely to hold positive views of CHWs and as a result engage them as integral members of the healthcare team at primary care clinics51. Thus, CHW program planners need to equitably engage representatives from communities and different healthcare provider groups that provide health services.

References

appendix I:

Search strategy, and study and methodological characteristics

Table A1: Study characteristics

Table A2: Methodological characteristics

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Determinants of an urban origin student choosing rural practice: a scoping review