Introduction

There are approximately 90 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled art centres, with the majority located in geographically remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Fig1). The term ‘art centre’ is used in this article to describe any organisation operating in Australia that is owned and controlled by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, where the principal activity is facilitating the production and marketing of arts and crafts. Art centres are diverse, like the communities in which they have been established. They are social enterprises that promote artistic practice and development, produce art for the market and exhibitions, and embed and reproduce culture and community priorities1,2. Many art centres were established by community Elders, and their boards comprised community members, including Elders, many of whom are senior artists within their centres. The centres employ predominantly non-Aboriginal art centre managers, who report to and represent their boards. The centres are often one of few places providing employment opportunities for local staff (with many remaining in their roles for many years) and provide the opportunity to earn an income from the sale of art3. Not only are staff and directors often artists themselves, they can be related through kinship systems, which means that many of the roles within the centres are multiple and interchangeable. The centres receive some funding from the Australian Council for the Arts, and generate income through commissions and sales. They are not funded to provide aged or health care services. It is estimated that 30% of the total number of people engaging with art centres across Australia are aged older than 55 years4 yet a review of the literature in 2017 found no studies that explored how arts centres respond to the needs of older people or people who may be living with dementia or other age-associated health conditions5.

This article is the first to address this gap in knowledge. It reports the results of a national survey that scoped how art centres support older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ wellbeing within a context of high rates and early onset of dementia and other conditions associated with ageing6-8, varied access to health and aged care services9, a growing ageing population and subsequent demand for services10. The high prevalence of dementia and other diseases in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is heavily situated within Australia’s ongoing colonial context11. This context results in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, like other Indigenous peoples across the world, experiencing ongoing health inequality through systemic structural racism, as well as social, economic and political marginalisation12-14. Recognising that models of care that centralise biomedical approaches have not always improved health outcomes provides a strong rationale to rethink the models that emphasise deficits rather than strengths, individual rather than collective identities, and medical expertise over cultural safety12. It also strengthens arguments that mainstream health systems should acknowledge the impact of these systemic power imbalances in perpetuating the production of illness. Instead, health systems should work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and community controlled organisations to envision how ‘care’ services could be co-designed to address these ongoing inequities15,16.

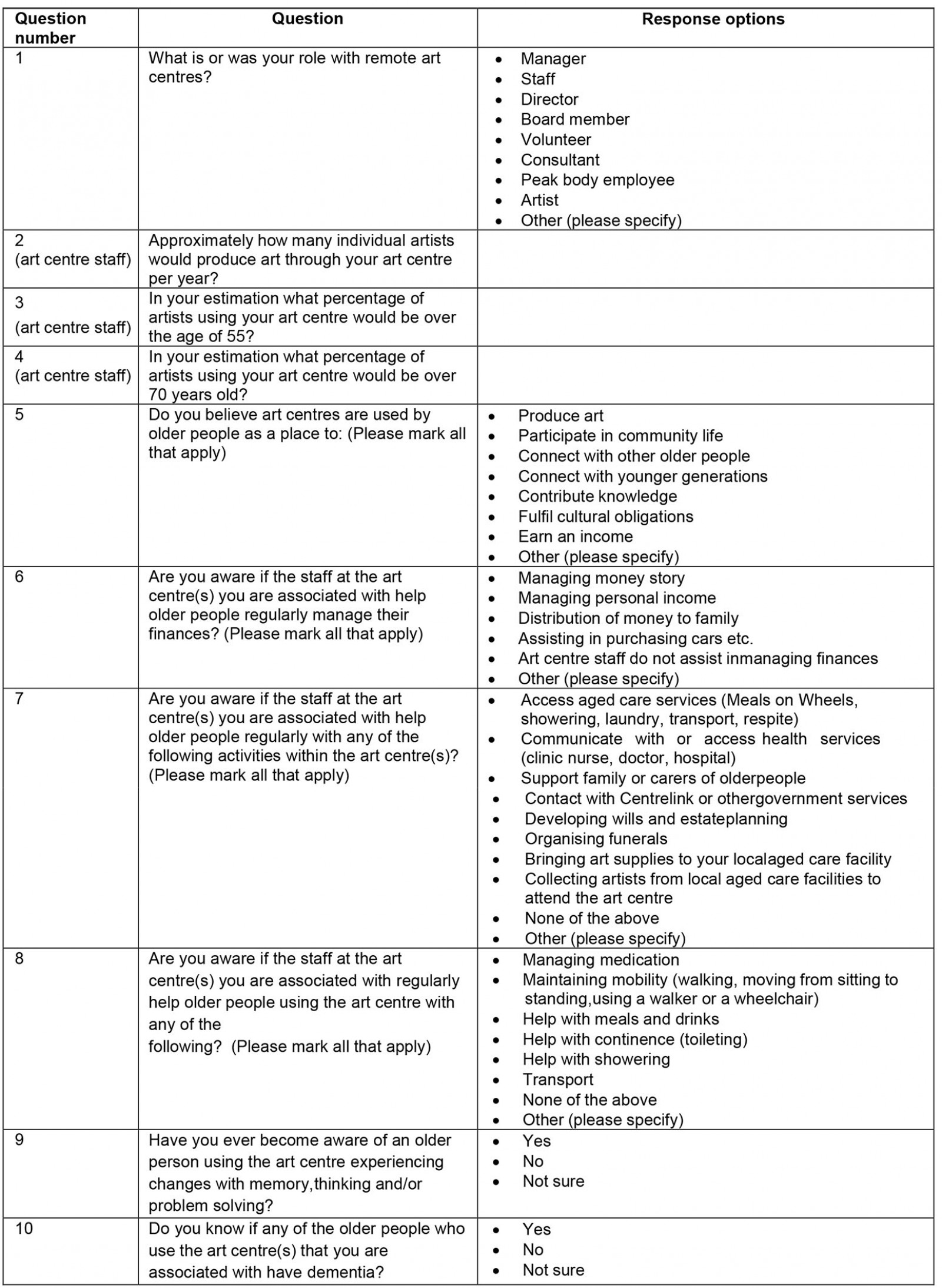

Figure 1: Map of Australia indicating the location of art centres (green) and aged care providers (red) throughout Australia. The map shows that art centres are primarily located in remote and very remote areas of Australia whereas aged care providers are predominantly located in rural and urban areas.

Figure 1: Map of Australia indicating the location of art centres (green) and aged care providers (red) throughout Australia. The map shows that art centres are primarily located in remote and very remote areas of Australia whereas aged care providers are predominantly located in rural and urban areas.

Methods

Research methodology

The online survey (conducted in SurveyMonkey) was developed as a quantitative survey in the context of an overarching qualitative participatory study that sought to understand how three specific Aboriginal community controlled art centres support their older artists17. The overarching study conducted semi-structured interviews and focus groups with 99 participants associated with three art centres and two aged care providers (51% of participants were artists, 25% were art centre staff, including managers, and 24% were aged care staff). The overarching study did not originally include a national survey; it was developed in response to a number of requests for involvement in the project from art centre managers from various art centres not included in the three partnership sites. The project team discussed these requests with members of the overarching study’s governance structure, which included three older Aboriginal artists and art centre board members, who directed the research team to proceed with a survey.

Survey design

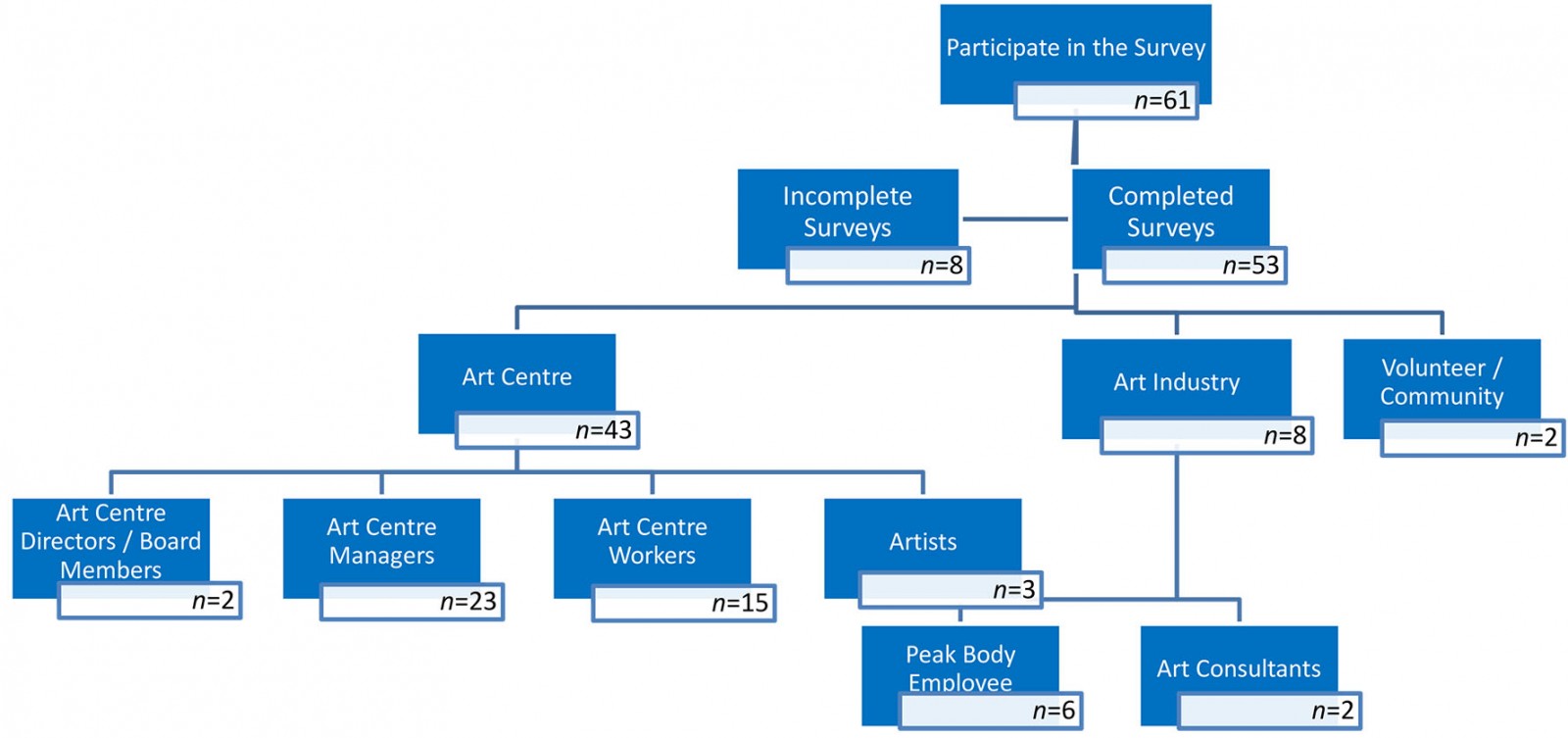

The survey was developed by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal members of the research team, with further input from members of the overarching project’s working, advisory and methodology fidelity groups. These included art centre managers, art centre consultants and peak body representatives. The survey was designed to capture the point of view of art centre managers and staff, although representatives of the overarching project’s governance teams requested it be open to artists and other interested parties who were closely affiliated with the centres. The survey explored the following research questions:

- Why do older people engage with art centres?

- In what ways do art centres support older artists?

- What existing collaborations currently exist between art centres and local aged care providers?

- What challenges do art centres face in supporting older artists?

- What do art centres need/want to maintain or enhance the support they provide to older people?

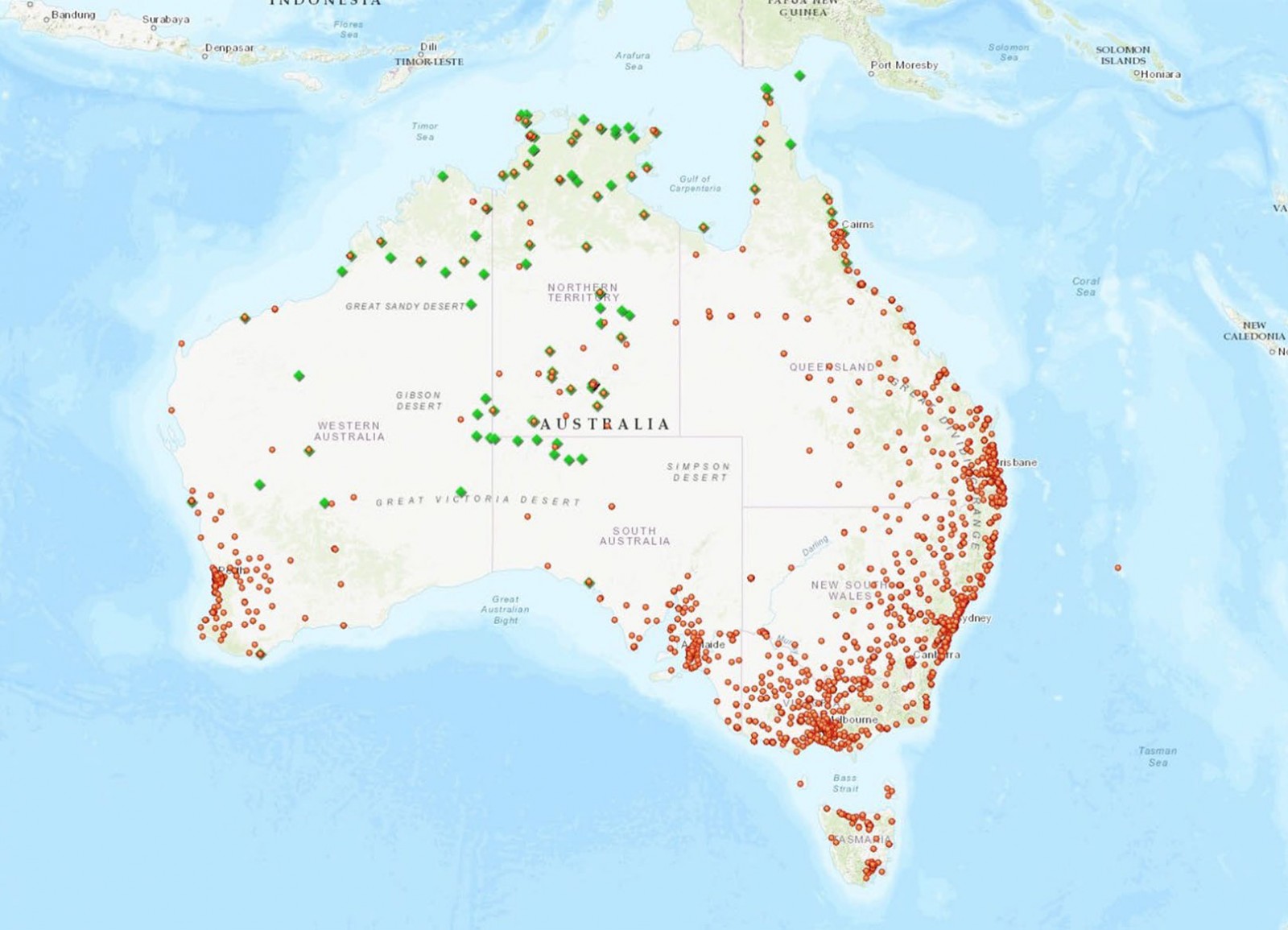

The survey was developed in English. Thirteen questions were presented, with eight additional questions for art centre managers, staff and directors/board members. These additional questions related to administrative data including the numbers of artists associated with the centre and their age breakdown, and how they perceive the ability of art centres to care for older artists (see Supplementary table 1). Quantitative data were collected primarily by multiple choice questions where respondents were able to choose as many answers as were applicable; and closed answer questions that provided ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘not sure’ and ‘not applicable’ options. Qualitative data were collected from free-text comments available on 13 of the 21 questions.

Distribution

The overarching study’s project working, advisory and methodology fidelity groups guided the survey distribution. Four Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art centre peak bodies (Desart, the Association of Northern, Kimberley and Arnhem Aboriginal Artists, the Indigenous Art Centre Alliance – Far North Queensland and Torres Strait Islands and the Aboriginal Art Centre Hub – Western Australia) emailed the survey link and information to member art centres across Australia. In addition, the survey was promoted during annual art centre events (including Desert Mob (Alice Springs), Revealed (Fremantle) and the Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair) and researchers conducted surveys face-to-face with participants at these events. Several surveys were completed by researchers during site visits to the three partner art centres, at which time researchers were introduced to staff at nearby centres.

Quantitative data analysis

Survey data was exported from SurveyMonkey into Excel for basic statistical analysis. Multiple choice and closed answer questions are presented as the percentage of people responding to the question that chose that response.

Qualitative analysis

The survey generated 330 free-text responses from the 13 questions that provided this option. Free-text responses were imported into NVivo v12 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home) for analysis. A deductive thematic analysis was initially conducted by KS using an inductive coding framework that was concurrently in development for the overarching project18. The overarching framework was developed by several Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal members of the research team. Initial analysis of the qualitative survey results was performed on the responses to each individual question. However, analysing the responses in this way highlighted that many of them related to a different question than the one they were entered under, or related to multiple questions. For this reason KS, PM, SF and JC made the decision to analyse the coded free text inductively, by emerging theme rather than question, to better understand the overall results18. The analysis identified themes that enriched information pertaining to the overall objectives of the survey. A new theme of ‘a safe place’ was identified from this process, which then informed the development of the overarching project’s coding framework19.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval to conduct the survey was obtained from the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (reference CA-17-2986).

Results

Response rate

The survey was conducted from 26 March to 23 October 2018. Sixty-one surveys were commenced; eight were removed due to incompletion, and 53 completed surveys were included in the analysis. Sample size was calculated on the population size of 90 art centres across Australia; 53 responses achieved a representative sample with a confidence level of 95% and a 9% margin of error. The authors acknowledge the nature of the survey made it difficult to determine if a single art centre was represented multiple times and as such this margin of error is likely to be underestimated.

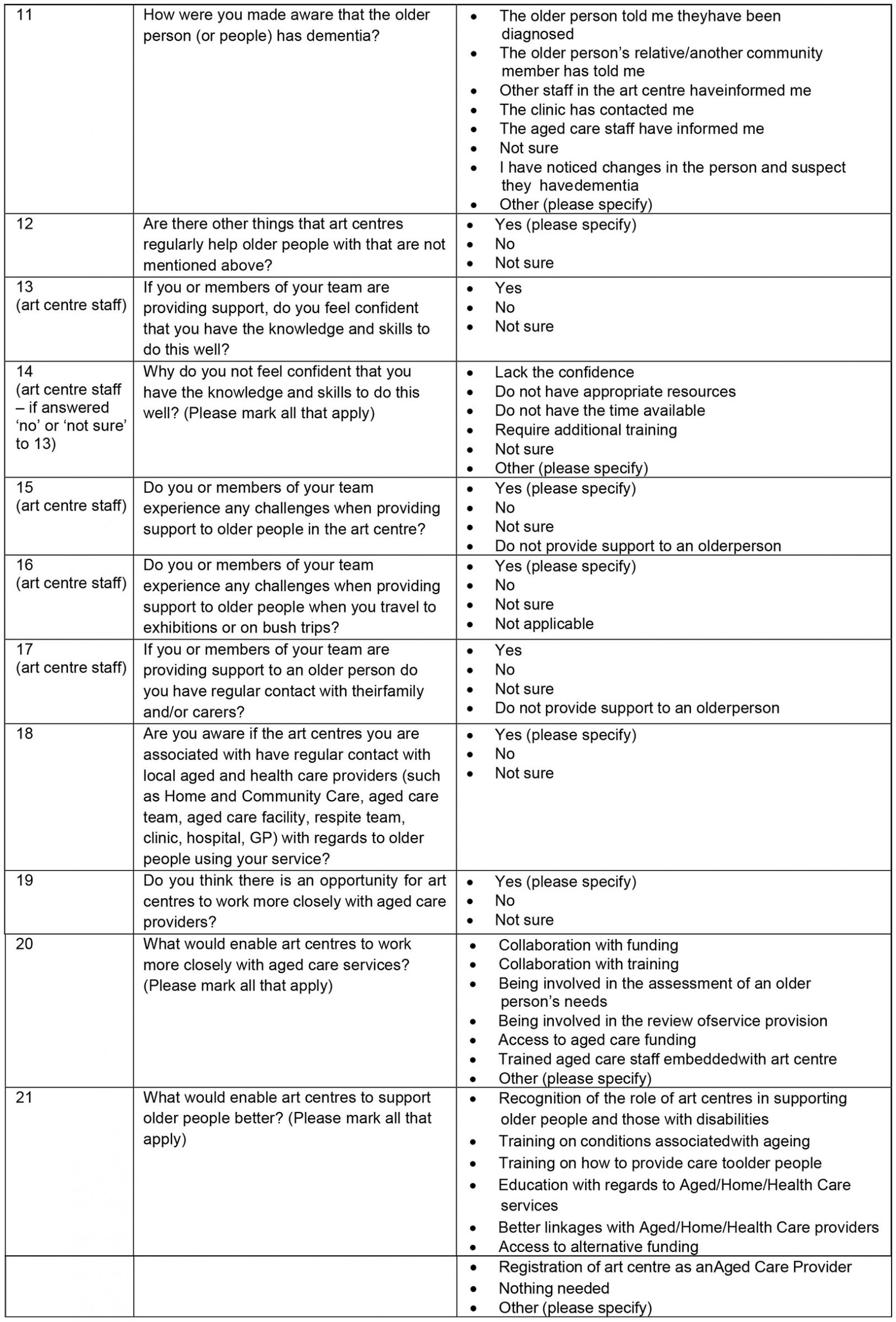

Of the 53 surveys, 71% (38) were completed online and 28% (15) completed in hard copy. Of these 15, 46% (7) were completed independently and 53% (8) were completed with a researcher, who completed the form (Fig2).

Figure 2: Response rate and demographic breakdown of art centre survey responses (n=53).

Figure 2: Response rate and demographic breakdown of art centre survey responses (n=53).

Respondents’ roles

Other than roles of survey respondents, no demographics were collected. Of the 53 completed surveys, 81% (43) identified as art centre staff, 11% (6) as employees of peak bodies, 4% (2) as art consultants and 4% (2) as volunteer or community members. Of those respondents from art centres, 53% (23) identified as managers, 35% (15) as workers, 7% (3) as artists and 5% (2) as directors/board members. Very few differences were noted in the responses so unless otherwise specified the answers from these professional subcategories have been amalgamated.

Respondents were provided with the option to include their email address to receive updates on the project. This information indicated that responses were received from the Northern Territory, Queensland (including the Torres Strait Islands), Western Australia and South Australia.

Themes

Three meta-themes, each with several subthemes, describe the reasons why older artists engage with art centres, how they support older artists, and how they collaborate with aged care providers. The meta-themes are a safe place, care provision and collaboration. These are illustrated using quotes from respondents attributed by their role. Some challenges and opportunities identified are also presented within these meta-themes. Figures 3–5 further report aggregate data findings.

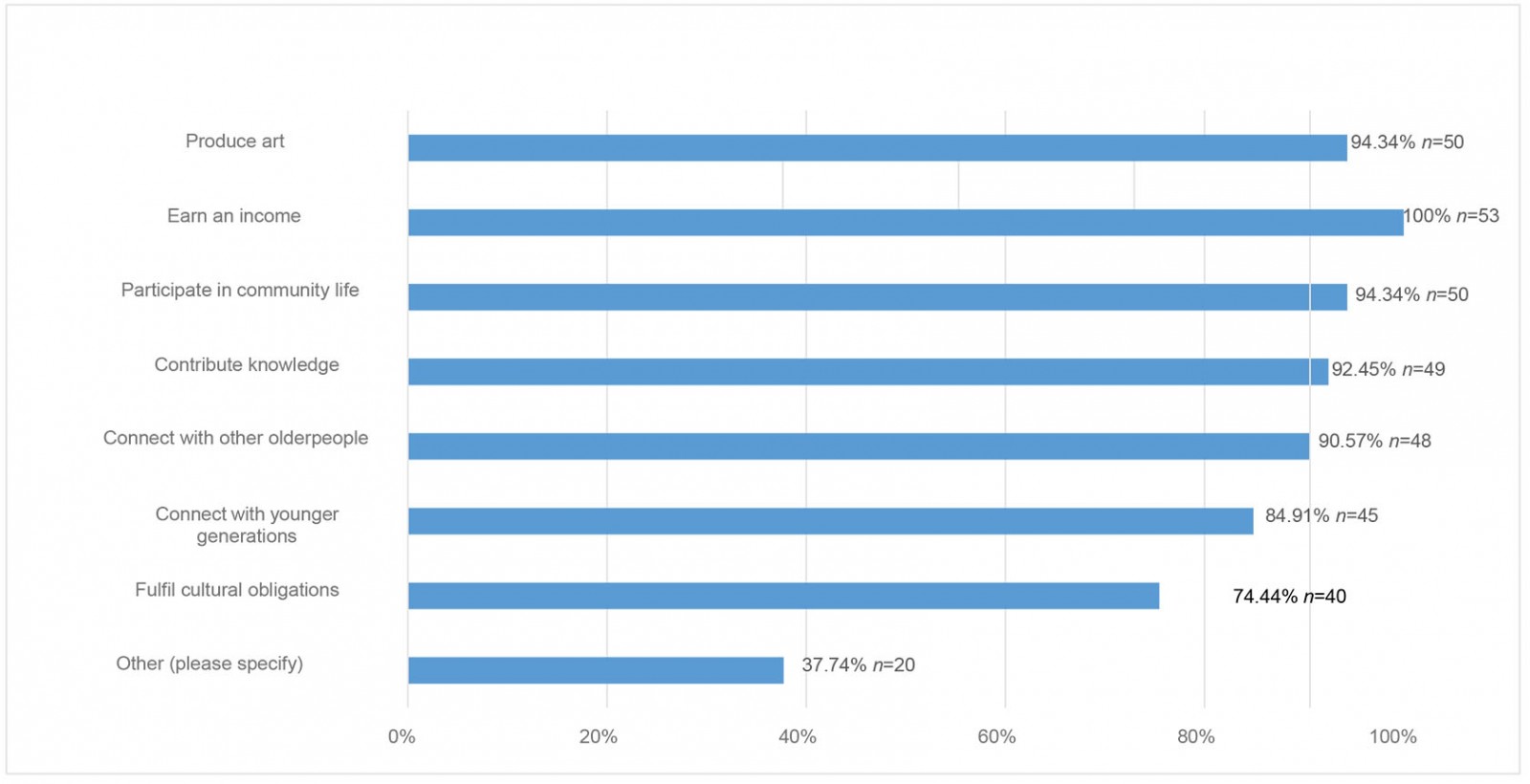

A safe place: Several subthemes were identified within the first meta-theme of ‘safe place’. These were that art centres are places for artists to work, earn an income and enact governance; fulfil cultural obligation through arts practice, storytelling and teaching younger generations; and safe support without a mainstream health or aged care agenda. All were identified as key to why older people engaged with the centres.

Work, income, and governance Art centres are a place to fulfil the older artists’ wish to engage in culturally appropriate work, to earn an income and provide oversight and governance.

The art centre is somewhere that is warm in winter and cool in summer. They can earn a good income to provide for their families, which is very important to them. (Art centre manager 5)

Work and purpose, direct governance etc. (Art centre manager 12)

Fulfil cultural obligations The art centres were identified as safe places for older people to participate in cultural obligations through arts practice, and to be with younger people and share knowledge.

This [practice] enables them to love, to tell this story to each other … [it is] a conduit to teach young people who to be careful of regarding law and culture, places you can go and places you can’t go (Art centre staff 5)

A Safe place where older people come and mix with younger people and share life and cultural info (Artist 3)

It is very important to emphasize the cultural value of passing an understanding of law and culture to the younger people. A lot of artists are worried about losing this knowledge. (Art centre staff 10)

Support without a mainstream health or aged care agenda Art centres are not official providers of health or aged care services, and there is no obligation to attend them to seek a service for a specific problem. This reinforced the perception of them being safe places.

General family support in a safe space without an agenda (eg health, aged care) (Art centre manager 7)

Figure 3: Why older people engage with art centres – multiple choice options selected by respondents.

Figure 3: Why older people engage with art centres – multiple choice options selected by respondents.

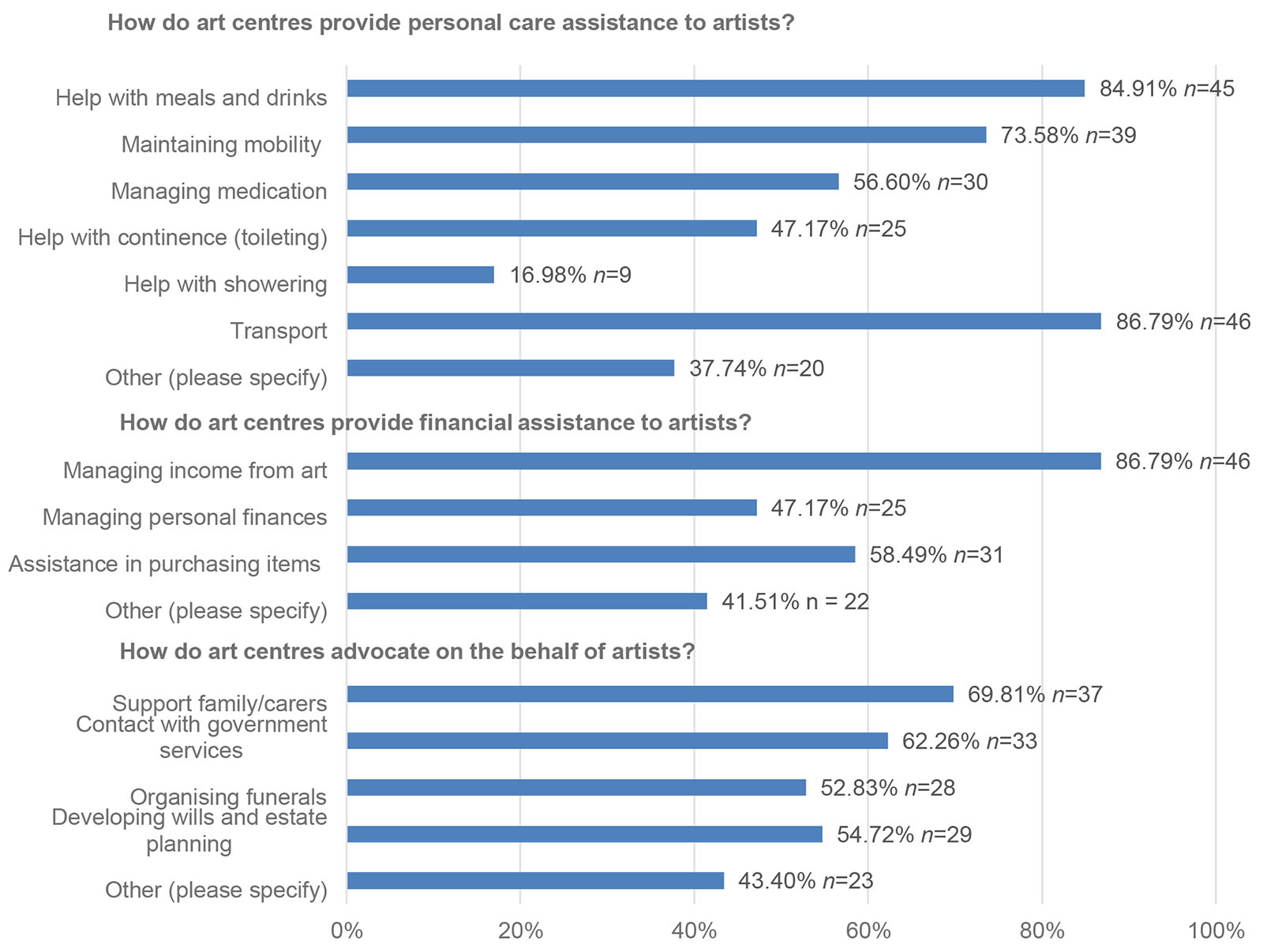

Care provision: Care provision was identified as the second meta-theme, with respondents indicating that art centres provide extensive support to older artists beyond the core business of producing art. Care included the subthemes of direct personal care and support with activities of daily living; providing transport; help managing finances and purchasing essential goods; advocacy; a form of respite for families; and caring for artists’ social and emotional wellbeing. Art centre staff reported ‘cultural and linguistic barriers to identifying health problems’ and the challenges of managing expectations of support from aged care and the artists and their families.

Direct personal care Personal care and physical support were some of the most common forms of assistance provided by art centres. This includes help with meals and drinks, mobility, medication management, toileting and showering (Fig4).

People’s well-being, ensuring they are comfortable, it’s paramount to [achieving] art we can sell. (Art centre staff 14)

Several respondents noted that this was difficult as their studio facilities lacked accessibility for many older artists, which potentially placed the safety of both artists and staff at risk.

We don’t have adequate ramps and handrails, shower chairs, etc. (Art centre manager 27)

I haven’t had any training. I'm worried about hurting myself with the ladies and their walkers. I would hate for either of us to get hurt. (Art centre staff 5)

Travelling with artists to exhibitions and bush trips or trips to Country presented challenges for staff, with the added difficulties of providing direct personal care when they were away from home and in unfamiliar environments.

Older people need a personal carer with them 24/7 … showering, washing clothes, overlooking medication is taken, taking them shopping, ensuring artists are fed etc. (Art centre manager 51)

We become travelling nurses on top of our regular responsibilities to the business and other artists. (Art centre staff 3)

Art centre managers, staff and directors were asked if they felt confident providing support, and 58% (23) responded ‘no’ or ‘not sure’. In response to why they did not feel confident, 67% (8) stated that they required additional training.

Further challenges noted in the free-text responses included how to respond to artists who are experiencing cognitive decline.

Difficulty with keeping dementia patients safe in a studio environment, not knowing if medication is being controlled properly etc. (Art centre manager 28)

Transport At 87% (46), transport was one of the most common forms of support selected (Fig4). This included transport between the art centre and the older artists’ homes, as well as transporting artists to shops, sorry camps or medical appointments. Getting in and out of vehicles was also noted as a challenge, especially ‘troopies’ (Toyota Troop Carriers).

We have a ladder to help them access the troopie (and sometimes use a bucket) (Art centre manager 1)

Getting people in and out of troopies, especially if they have walkers and the ladies hold on to them (Art centre manager 30)

Drop off elderly to their home after painting. We support them to get into the troopy. (Artist 2)

Managing finances and purchasing essential goods and services Managing finances included estate planning, organising funerals and organising the development of wills. Examples of purchasing essential goods such as cars, clothing, mobile phones, bus tickets and bedding were provided (Fig4). Respondents emphasised that providing support with these types of activities created an environment where artists felt comfortable, welcome and happy to work.

We help people to manage their money to the extent they want us to help them. Different art centres do things different. (Art centre consultant 13)

Advocacy Advocating for older artists was another subtheme of care provision, with art centre staff helping navigate significant language barriers and to increase access to services in the ‘white-fella world’. Respondents stated they would assist older artists with government services (Fig4) and provided examples of ‘making sure they get to … court appearances’, ‘interpreting letters’ and ‘making emails, using phones, reading forms and taking phone calls’.

There is a disjointed relationship between community reality and services and the art centre is trying to bridge this gap. (Art centre manager 3)

We had 2 staff members spend a week on 2 separate occasions in Perth with a senior artist who had broken their hip, calm and reassure/sit with/spend time with/shower/help with sleeping- the old person every day as family would stay the whole time and hospital didn't have enough staff to assist or translate/interpret (Art centre staff 4)

Respite Art centre staff reported that they were in regular contact with the families or carers of older artists. This enabled a deeper understanding of an artist’s social situation and facilitated the provision of support to families and carers (70%, 37) (Fig4). Free-text responses under a number of questions indicated that this support generally takes the form of acting as ‘respite care’ for older people.

Mental and spiritual health Trips to connect with Country, culture and fulfil their roles as Elders was identified as a key component of the care provided.

Trips, especially to the bush, have enormous benefit to the mental health of the old people, and yet it requires time to work out arrangements for those people to ensure they are able to attend (Art centre manager 17)

Figure 4: Art centres support older artists by providing personal care assistance, financial assistance and advocacy – multiple choice options selected by respondents.

Figure 4: Art centres support older artists by providing personal care assistance, financial assistance and advocacy – multiple choice options selected by respondents.

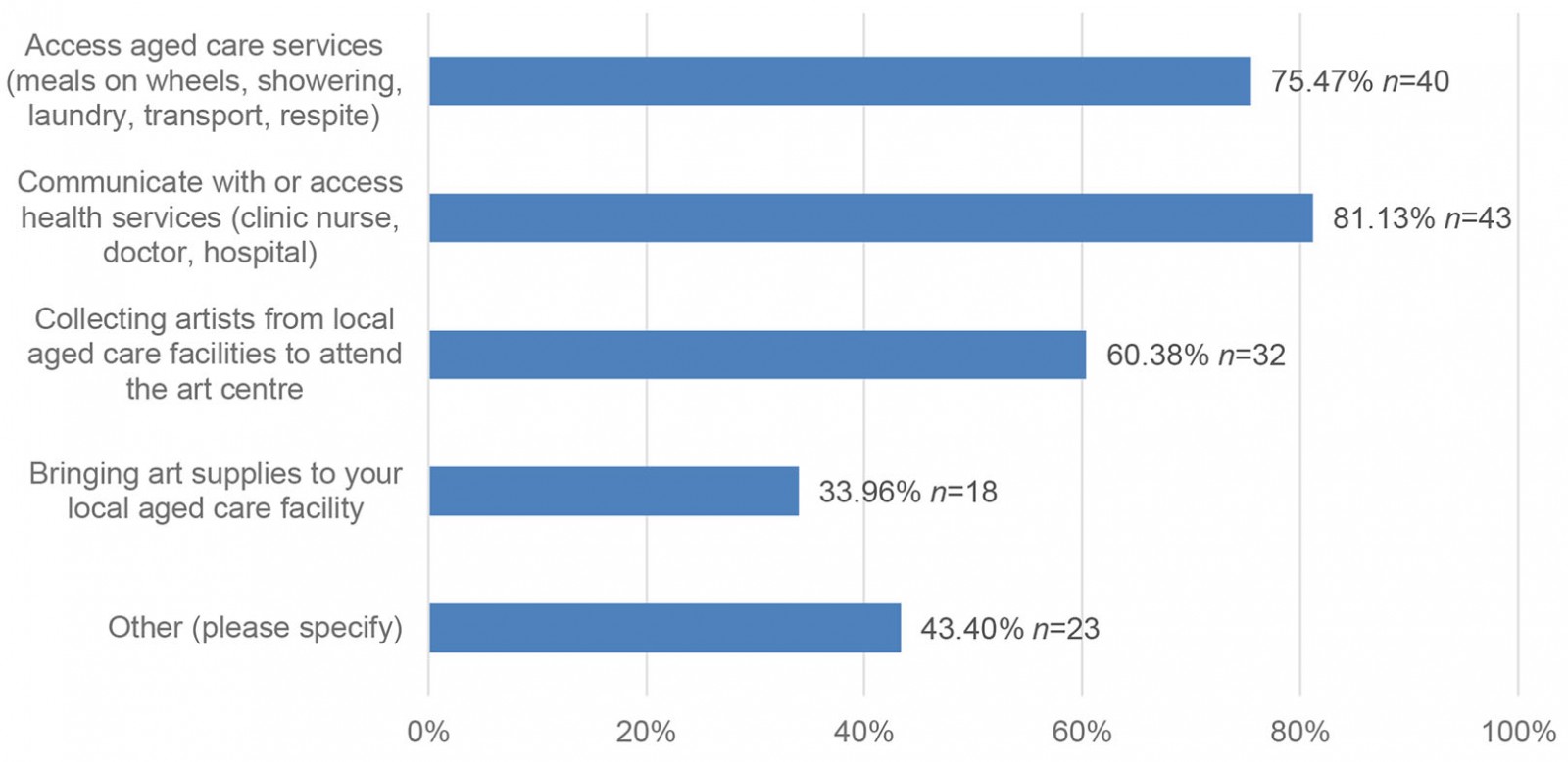

Collaboration: The third meta-theme is collaboration between art centres and health and aged care providers. The subthemes are communication, service navigation facilitated through relationships, and sharing infrastructure and expertise. Collaboration was noted as positive, but time intensive, particularly in contexts of resource limitations.

Communication Communication between art centres and aged or health care services was commonly reported by respondents. Seventy-five percent (40) reported their art centre was in regular contact with local aged care and healthcare service providers. This increased to 82% (14) for art centre workers and 91% (21) for art centre managers.

Service navigation facilitated through relationships Over 75% (40) reported helping older artists navigate access to aged care services, such as Meals on Wheels, showering, laundry, transport or respite services. Eighty-one percent (43) reported helping people to communicate with or access health services (such as hospital, general practitioner or clinic nurse) (Fig5). Many staff indicated they gain unique insights into the health, wellbeing and social situation of their older artists through regular contact with artists and that this information would be of great benefit to other service providers.

We typically have much better relationships with elderly artists than staff in the health centres, we can get more done for them because of this. (Art centre staff 27)

We see people regularly, we report to aged care and clinic, we notice changes physically and cognitively, how they hold a brush, changes on the canvas, channels of communication, it is all very important. (Art centre staff 14)

However, not all respondents knew how to access health and aged care services as they are not necessarily connected with local service networks.

I notice something about an older artist but I don’t know what to do about it … I don’t know who to speak with. (Art centre staff 9)

Sharing infrastructure and expertise Many of the respondents reported that aged care services deliver Meals on Wheels directly to the art centres. Art centres facilitate transporting artists to and from the local aged care facility (60%, 32) or bring art supplies to the local aged care facility (34%, 18) (Fig5). Two respondents indicated that their art centre collaborates with the local residential aged care provider to run a painting therapy program for residents.

The painting therapy program we run has been going for over ten years and has been hugely successful as it connects Aboriginal aged care residents with their culture and family and enables the older artists to share important tjukurrpa [law and culture] before they pass on. It also helps to alleviate the boredom of being in an aged care facility and away from family. (Art centre manager 54)

As mentioned previously, in the meta-theme of care provision, respondents thought working alongside health workers, to share resources and expertise, would be ideal.

Health care workers with the resources to work alongside the art centres would be more appropriate (Art centre staff 6)

I hope in the future that there will be more working together, in the past this happened a lot. (Artist 1)

Figure 5: How art centres collaborate with local aged care and healthcare providers – multiple choice options selected by respondents.

Figure 5: How art centres collaborate with local aged care and healthcare providers – multiple choice options selected by respondents.

Discussion

The survey is the first of its kind to explore how older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, including those living with dementia, engage with their community controlled art centres. Respondents, primarily art centre managers and staff, report multiple and interwoven reasons for engagement. These include that art centres are seen as a safe place to earn an income, which enables older artists, many of whom are Elders, to fulfil their roles and responsibilities to provide for their (often) large families. The importance of this cannot be underestimated in geographically remote communities, where access to employment is limited and the cost of living high. Importantly though, the respondents emphasise that the reasons for engagement are not limited to economic outcomes, despite art centres being mainly funded for economic purposes3,20. For older artists, who are often cultural authorities and in the prime of their career, art centres provide routine, purpose and work that places a high value on their cultural knowledge. Workplaces that enable a worker to participate in cultural obligations are more likely to be associated with wellbeing21.

Similarly to other studies, the crucial role of Elders in teaching younger generations and the importance of having a safe place for this to occur was emphasised22-24. While this concept can be interpreted as one of comfort from extreme weather conditions or overcrowded and unsafe housing common in remote communities25, it also includes the concept of cultural safety. Developed in the colonial context of Aotearoa, New Zealand, cultural safety places an obligation on those providing care to acknowledge power in relationships, and to recognise and respect difference26. Furthermore, the concept requires the user of the service to decide if they feel safe26. Cultural safety is evidenced in the survey results by the voluntary manner in which the older artists engage with their centres in multiple ways and on their own terms. The community controlled model also plays a pivotal role in the art centres’ day-to-day operation and the Elders, as the knowledge keepers, are at the core of this model, enhancing and reinforcing the centres as safe places.

Respondents emphasised that the older artists’ engagement is underpinned by the purpose of connecting with their communities, Countries, and families; fulfilling their roles; and practising their beliefs and knowledge systems. All of these are upholding the cultural determinants of health27,28 and reflect a deeply interwoven and relational worldview emphasised by key Indigenous scholars29,30. Additionally, if the community controlled art centres are perceived as culturally ‘safe’ and potentially free from structural racism by older art centre participants, they hold many lessons for mainstream institutions funded to identify and respond to the health and care needs of Australia’s remote-dwelling ageing populations10.

The results indicate that the model of care provided by art centres is directed by the older people or their families, rather than being stipulated through funding or regulated by mainstream mechanisms. The nature of care provided manifests in diverse ways, and respondents indicated it is facilitated through interpersonal relationships between staff, the artists and their families, and staff relationships with health and aged care services within their communities. Respondents also noted the provision of this support was necessary for artists to feel comfortable to engage in their work. In addition to prioritising relationships, the model embeds the Indigenous concept of reciprocity30,31 where the artists work for the centre and their community, and the centre cares for artists, which in turn assists them to practise their multiple roles within the centre and beyond.

Facilitating bush trips to support the wellbeing of older artists and the production of art and culture was reported. These trips provide opportunities for cultural practices such as gathering foods, painting, weaving and sharing stories on Country3, and are important to maintain a connection to Country and culture21,32; wellbeing32,33; the cultural determinants of health28; as well as supporting a good quality of life for older Aboriginal peoples34. The difficulties of older artists who experience a decline in their mobility have with safely entering and exiting vehicles was identified as a dilemma by respondents who, in line with recent research, recognised the profound benefits of being on Country for health and wellbeing35-38.

It is noteworthy that, unlike programs that are funded to deliver aged care services, art centres are not bound by siloed funding categories that mean they are exclusively places for older people. They do not categorise artists according to diagnosis or age; instead, all are welcome, strengths are emphasised, business agendas are self-determined, and opportunities for connection and teaching and learning between generations abound. These elements have been identified as fundamental to Aboriginal people’s wellbeing21. They echo calls to abandon ‘one size fits all [and] same system[s] thinking’39 as well as dominant biomedical hierarchies in health care in favour of locally responsive holistic approaches that learn from and are led by Australia’s First Peoples40,41. In addition to providing care without aged care funding, the centres are doing so with infrastructure that is not easily accessible, and a workforce not necessarily trained to identify and respond to chronic care needs, or with an understanding of how to access funded care programs (if available). The multiple responsibilities and expectations to provide care for artists within such under-resourced environments has been identified as contributing to exhaustion and burnout of art centre managers42.

While respondents have indicated that many art centres collaborate with their local aged care and health services, respondents also indicated the need to recognise and resource these collaborations. Rather than formalising responsibility to deliver funded aged care programs themselves, the art centres want to work alongside their local aged care in ways that work for both organisations. Integrating shared models of care between aged care and art centres is outlined in one recent example through a trial of co-location in a very geographically remote part of Western Australia. The partnership between two Aboriginal community controlled organisations was described as mutually beneficial by both parties. Benefits include sharing infrastructure, which is often scarce in remote communities; reducing stigma associated with accessing aged care services; promoting belonging and integration for all generations; and enabling people to raise and have their concerns addressed in an indirect and trauma-informed manner43. Although in their infancy, such models have the potential to break down mainstream siloes and align operations with holistic ways of conceptualising health and wellbeing. This example aligns with previous calls to tackle dementia awareness outside of the domain of aged care services in remote Aboriginal communities44.

Importantly, the results speak directly to the recommendations from the Australian Royal Commission into Quality and Safety in Aged Care that indicate aged care providers need to deliver care that facilitates connection to Country, cultural safety and consider integration with existing community controlled organisations45. They also align with calls from Indigenous scholars to rethink mainstream models of care that centre the biomedical aspects of an individual’s health towards models that are self-determined and led by communities. Models are required that embed the holistic definitions of health23, promote cultural expression and cultural safety28, and prioritise connection to Country in health and wellbeing21,46. Further exploration about how the art centres could be recognised, resourced and implemented within Australian aged care, health and disability policy frameworks is warranted.

Limitations and future research

As noted, the survey was in English and many people who work at art centres do not speak English as a first language. As a result, the survey may not include a representative proportion of responses from the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander workforce. Only three respondents identified as artists and more research is needed to understand the role of art centres in supporting older artists from the artists’ point of view.

Conclusion

The survey reveals Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled art centres play a wide ranging and vital role in their geographically remote communities. Managers and staff perceive the centres as safe spaces that enable teaching and learning, that also provide physical, social, spiritual, cultural and economic care, all of which support the holistic health of older people, who are often the cultural pillars of the art centre. Many respondents report it is the nature of this support that enables the older people to participate in the day-to-day business of their art centres, whether that be as an artist, a staff member or a director, and therefore meet the overall economic and cultural objectives of these social enterprises and their broader communities. Furthermore, the intergenerational connections enabled by art centres may have a role in contributing to broader community wellbeing. The survey results indicate that, although provision of care is facilitated through strong relationships, it is not without its challenges for staff, who report dilemmas in managing these under-recognised and unfunded care requirements within the already under-resourced context of running the centres. The survey also revealed that, although a great deal of collaboration already exists between art centres and their local aged care and healthcare providers, little of it is formally documented or arranged. The results of this survey provide an opportunity to recognise the value of art centres in providing culturally responsive and safe care in geographically remote communities experiencing high rates of chronic disease, variable access to health and aged care services, challenges with workforce recruitment and retention, and a growing ageing population. They also provide a prompt for health services, aged care providers and art centres to re-imagine models of care in geographically remote locations and, together with funders and policymakers, consider how to resource and implement them.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the many Countries on which we live and work. We pay our respects to the First Peoples of these Countries and to their ancestors and Elders past and present. We would also like to acknowledge the Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara peoples of Tjanpi Desert Weavers, Pintupi-Luritja peoples of Ikuntji Artists, and Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Walmajarri, Wangkajunka and Nyikina peoples of Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency for their ongoing methodological and ethical guidance of the overarching program of research this study sits within.

The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank the participants of this study, as well as members of our Project, Advisory and Methodology Fidelity Groups for their comments on early drafts of the survey tool.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Australian Government Department of Health and Erica Foundation Pty Ltd.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/6850/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2006 - SEAM - improving the quality of palliative care in regional Toowoomba, Australia: lessons learned