Introduction

In their seminal book Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty, Acemoglu and Robinson, in their endeavor to explain the factors that are responsible for the success – or failure – in terms of collective welfare of states, proposed a groundbreaking theory1. The key concept behind the Acemoglu and Robinson proposal is that economic prosperity of a nation is closely related to the degree of inclusiveness of its economic, political and legislative institutions. Inclusivity, a central notion in this theoretical proposal, is characterized by the strong presence of the state (‘a state with capacity’2) and a broad distribution of power of decisions. Conversely, a significant decrease in potential collective welfare occurs when the institutions in a society are extractive – when they are built in such a way that they permit a closed group of people (an elite) to exercise market power and extract wealth (welfare, in a broad interpretation) from those who are not part of the elite. The general population, in that sense, are those who lose from a system with extractive mechanics (ie a system with exclusivity).

The dialectics about the role of institutions in shaping the broader social environment can provide a useful insight regarding the way that the macro-level dimensions of a society can influence the activities and behaviors in the individual (ie at the micro-level)3 and, to that end, the results in terms of collective welfare. Institutions in a society are created out of subjective human interaction but are perceived by participants as objective and stable4. In other words, institutions form the rules of the game within a society5,6, and a close inspection of these interactions between persons and institutions introduces a new approach regarding the study of social, economic and political dynamics7 in such complex systems.

Among the complex subsystems that constitute a society, the healthcare ecosystem retains a leading role. However, the examination of the role of institutions in shaping healthcare markets and individual behaviors remains less explored compared to studies in other societal systems. Discussions tend to focus mainly on the nature and evolution of institutions in health care from an organizational sociology point of view8 or, in some cases, on the relationship (and the distinction) between institutions and formal organizations in health care9, and the role of institutions in organizational change10. Newer contributions in the topic discuss the role of institutions in areas such as the system-level responses to emergency situations in health11 or the influence of institutions as moderators in health behaviors12 and in health planning13, although these veins of work are still evolving. In this view, the investigation of the effects of the characteristics of institutions on the collective health outcomes or total welfare remains an unexplored path.

The concept of inclusion, on the other hand, regarding applications in health, has been used mainly from the perspective of social rights and participation14,15, or to describe health services that are equitable, affordable and efficacious16,17. Acemoglu and Robinson depict a different view on inclusivity, where, as already noted, the state has a crucial role. This role is performed through a set of attributes of the strong presence of the state, such as the securing of access for the great majority of its citizens to a range of basic opportunities, for example education (or, by extension, health), the provision of public services and the production of public goods2. The opposite of this pluralistic organization of societal infrastructures are the extractive institutions: extractiveness thrives when there is concentration of power (political or market power) in specific groups of the population18 who, in turn, can operate in imperfect market structures, such as monopolies, oligopolies and monopolistic competition. Such arrangements, between supply and demand, typically lead to loss of total surplus – to decreases in total social welfare compared to more pluralistic forms of markets (eg perfect competition).

In this light, the Acemoglu and Robinson theory provides a new perspective into the role of institutions in the increase and distribution of societal welfare. Taking into account that one of the pillars of the modern welfare state is its health system, this article attempts to explore, largely based on the Acemoglu and Robinson proposal – and at an expansive interpretation – whether the degree of inclusivity of a health system could be related to improved welfare. In other words, using the terminology proposed by Acemoglu and Robinson and adapting it in the health setting, the research question that this brief analysis attempts to explore is whether inclusive health systems perform better, compared to extracting systems, in terms of their outcomes in collective welfare, as the latter is expressed through healthy life expectancy.

Methods

The analysis is based on the exploration of publicly available data by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)19. Given the widely acknowledged synergistic relationship between health, welfare and economic benefit20 the analysis utilizes an indicator of population health as a proxy for collective welfare: healthy life expectancy at the age of 65 (HLE_65). HLE, in general, represents the number of expected healthy years of life for individuals at a given age21. HLE summarizes mortality and morbidity in a single summary measure of average population health22 and constitutes a key indicator of collective health status23.

The analysis explores the relationship between HLE_65 and four variables that are potentially indicative of the institutional inclusivity or exclusivity of health systems:

- the share of public expenditure in total health expenditure (ie the share of expenditure from government/compulsory schemes in the current expenditure on health from all sources)

- spending on collective services and, in specific, spending on preventive care, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) (ie the total expenditure for prevention in each country, expressed as part of the corresponding year’s GDP)

- market power of physicians (expressed as the concentration of physicians, ie physician density, across regions in a country, by territorial level 2 regions)

- share of generalists in the total number of physicians in a country (measured as the total number of general practitioners to the total number of practicing physicians in a given country).

The sample of the analysis consists of all the European countries that are members of OECD. All data refer to 2018 (last available data at the time of the present analysis), apart from the third point (market power).

Results

A stronger presence of the state, in terms of public healthcare spending, is associated with a higher HLE at age 65

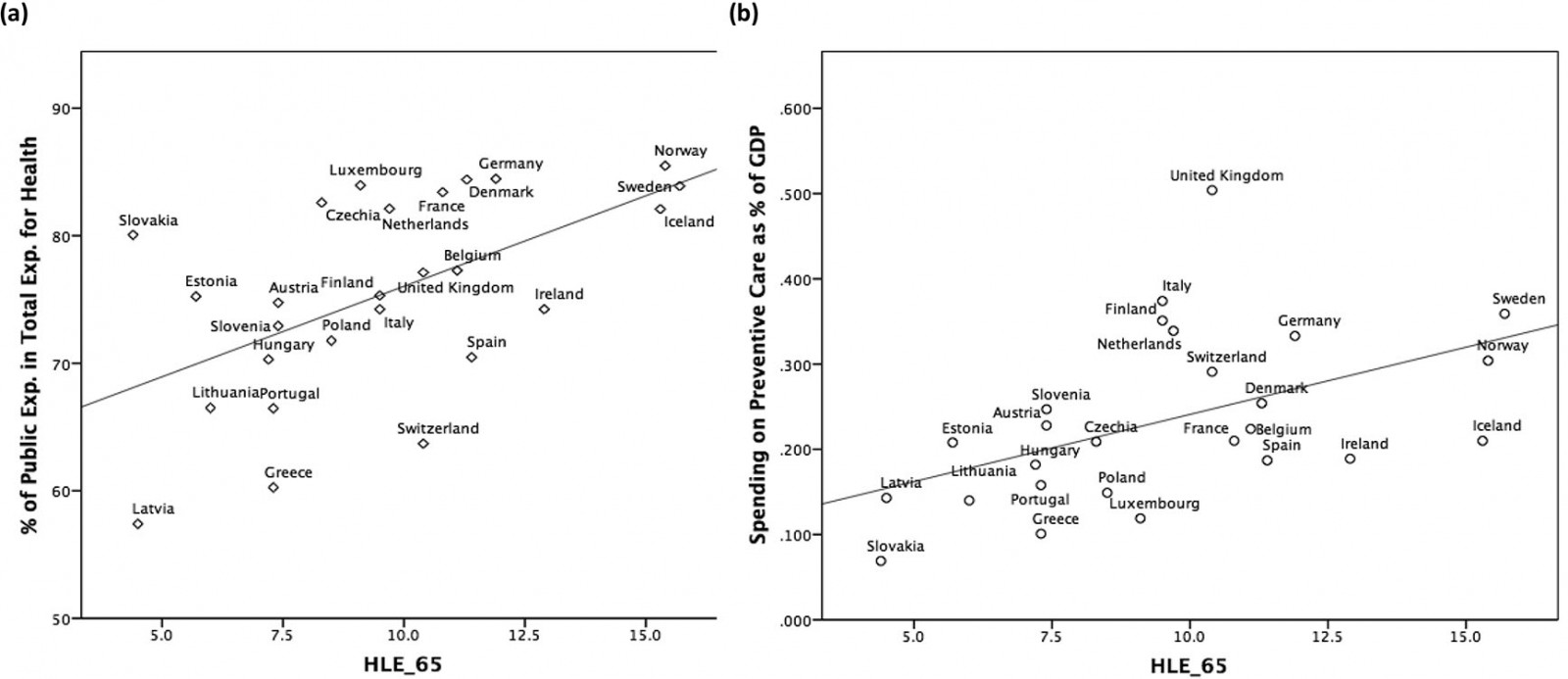

A moderate (Pearson’s r=0.557) but statistically significant (p=0.003) correlation is observed between the share of public expenditure in total healthcare spending and HLE_65 (Fig1a). On average, for every 10 percentage point increase in the public share of healthcare spending, HLY_65 is expected to increase by 2.18 years.

Systems with predominantly public spending on health appear to achieve better outcomes in terms of the number of years lived in full health, after the age of 65 years. An explanation for this finding could be that systems with higher public expenditure on health appear to demonstrate higher equity in health outcomes by closing the health gap between the poor and non-poor strata of the population24 and provide better opportunities for a healthy life by reducing child and infant mortality25. The share of public health expenditure, (ie the strength of the presence of the state) is related to the level of out-of-pocket spending26 and, by extension, to protection from catastrophic health expenditure27 and from the occurrence of unmet healthcare needs28.

Higher spending on prevention is associated with a higher HLE at age 65

Expenditure on preventive care, measured as percentage of GDP, is significantly correlated with HLE_65 (r=0.490, p=0.011). A 0.1% of GDP increase in spending for prevention is associated with an addition of 1.51 years in HLE_65 (Fig1b)

The benefits of prevention are universally acknowledged. However, another aspect of prevention, and especially one of its institutional characteristics, could be a potential explanation for this effect. State-organized preventive services, such as universal screening programs, are collective services, designed to have no barriers in access, and are thus by definition inclusive.

Figure 1: Strength of inclusive institutions of health systems and their effect on healthy life expectancy19. (a) Relationship between share of public expenditure in total health expenditure and HLE_65. (b) Relationship between healthcare expenditure on preventive care (as % of GDP) and HLE_65.

Figure 1: Strength of inclusive institutions of health systems and their effect on healthy life expectancy19. (a) Relationship between share of public expenditure in total health expenditure and HLE_65. (b) Relationship between healthcare expenditure on preventive care (as % of GDP) and HLE_65.

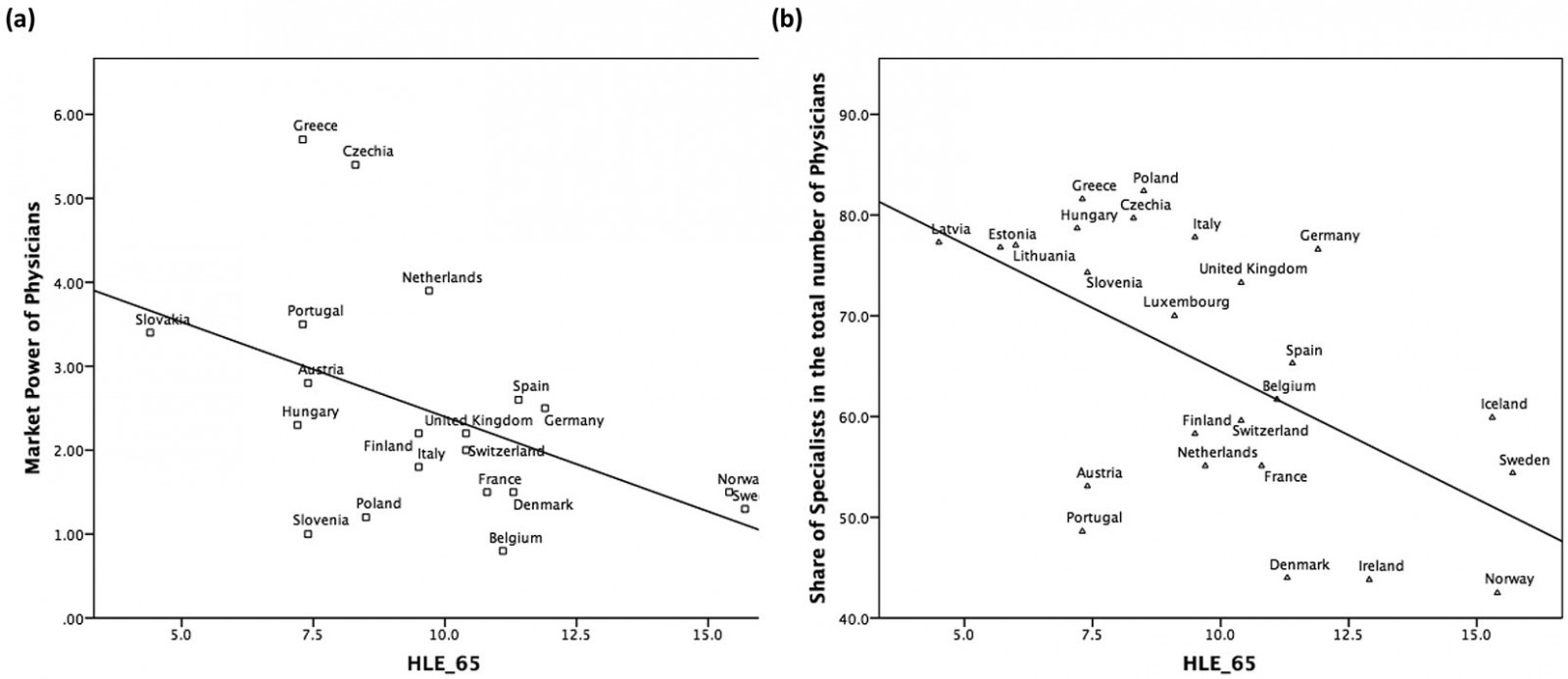

The market power of physicians is inversely related to collective welfare

For the approximation of market power the analysis uses the density of physicians in geographic areas and, specifically, the OECD’s estimates of physician density (physicians per 1000 population) across localities, by level 2 regions29. For each country the difference between the regions with the highest and the lowest density is estimated. We believe that this is a better demonstrator of the market structure of physicians in each country, compared to the overall physicians per capita estimates, since it indicates the areas of high or low concentration of the supply side. Our measure (ie the magnitude of the difference) shows the degree of uneven distribution and, thus, areas with strong market power of physicians. Significant market power of physicians, (ie stronger tendencies towards oligopolies/monopolies), leads to influence over prices and, thus, to an extracting mechanism that moves consumer surplus towards suppliers.

A special case is that of areas with high concentration of physicians. Although it would be expected that this could lead to competition for a market share, evidence points to the opposite; according to Dunn and Shapiro physicians in more concentrated markets charge higher service prices through being able to exercise market power30. Monopolistic behaviors may lead to less supply of services and lower efficiency of spending, especially for those populations that live in countries with high exposure to healthcare spending (extracting systems).

As shown in Figure 2a, uneven distribution of physician density is negatively correlated with HLE_65 (r=–0.458, p=0.042).

More specialists compared to generalists can lead to a loss of welfare

The share of specialists in the total population of physicians is inversely correlated (Pearson’s r=–0.575, p=0.003) to HLE_65 (Fig2b). Specifically, a 10% increase in the share of specialists is associated with a reduction in HLE_65 by 1.3 years.

A possible explanation for this trend could be dual. On the one hand, according to published studies systems with a high percentage of generalists tend to use fewer resources but at the same time achieve similar health status outcomes – thus achieving efficiency31-33. This should be combined with the fact that a stronger presence of general physicians is the basis of a stronger institutional primary care, which is less monopolistic (less extracting) and is associated with improved access, better population health and greater equity (ie inclusivity)34,35.

Figure 2: Strength of extracting institutions of health systems and their effect on healthy life expectancy19. (a) Association between difference in within-country density of physicians (areas with highest – areas with lowest density of physicians per 1000 population) and HLE_65. (b) Relationship between share of specialists in total number of physicians and HLE_65.

Figure 2: Strength of extracting institutions of health systems and their effect on healthy life expectancy19. (a) Association between difference in within-country density of physicians (areas with highest – areas with lowest density of physicians per 1000 population) and HLE_65. (b) Relationship between share of specialists in total number of physicians and HLE_65.

Discussion

Health systems are core social institutions functioning ‘at the interface between people and the structures of power that shape their broader society’36. In this sense, equity in access to health services and efficiency of spending are prerequisites of both a democratic society37 and an increase in collective welfare.

This analysis attempted to examine whether the inclusivity or exclusivity of a health system, with both terms based on a broad interpretation of the theory of Acemoglu and Robinson in the case of health, affects collective welfare, as proxied by estimates of HLE at the age of 65. In doing so, the analysis uses publicly available data and finds positive correlations between HLE_65 and the strength of the presence of the state in terms of financing the health system and the investment in collective actions such as preventive care. On the contrary, loss of welfare is associated with market power of physicians and the overwhelming presence of specialty care compared to general physicians/primary care.

Certainly, correlation does not equal causality. Also, the issue of the production function of a health system, in terms of its analytical scope, remains a subject of debate, with promising contributions coming from the application of standard economics methods, such as the use of the Cobb–Douglas production function, in the field of the production of health38. Nevertheless, the findings of this analysis can be of high importance to the health and welfare of populations living in remote and rural areas; the uneven allocation of physicians, which is typically expressed with lower densities in rural areas39,40, can lead to lower healthy life expectancy at the macro level, as shown from the findings of this study. In the same context, the absence of investment in collective actions (such as population-based organized screening programs) is associated, based on the macroscopic findings of this study, with reduced health life expectancy (on a country basis), which can disproportionately affect rural populations41. This effect is intensified when the population is exposed in private spending for screening42, in line with the findings of the study that demonstrate that when the public presence in healthcare expenditure is stronger (ie private spending is lower), the results in collective welfare are better.

Conclusion

The organizational characteristics of institutions in a society can play a major part in terms of their results on collective welfare: according to Acemoglu and Robinson, inclusive institutions, characterized by a democratic expression of the power of decisions and a strong presence of the state, appear to increase collective welfare, compared to extractive institutions (ie systems where the power of decision-making is limited to the hands of closed groups of people). The results of the present analysis indicate that this approach can be applicable in health as well, given that systems with inclusive characteristics appear to perform better in terms of health outcomes, as expressed through measurements of healthy life expectancy. In this sense, policies that aim to strengthen the inclusivity of a healthcare system, such as the focus on prevention – especially in populations that face geographical, time or cost barriers in access to health services, the focus on financial protection and the avoidance of catastrophic expenditure on health, and the strengthening of public health and primary care – could have a significant positive effect in collective welfare and social cohesion, especially for populations in less developed parts of the world.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Eleftheria Karampli and Dr Michael Igoumenidis for their insightful comments during the drafting of this manuscript.