Introduction

Urban–rural equity of healthcare provision is a challenge throughout the world, in countries of widely varying socioeconomic development1. While half the global population lives in rural environments, only 24% of medical doctors live in rural environments1.

Many strategies to improve recruitment and retention of healthcare workers into rural and underserved areas have been proposed and implemented, which a Cochrane systematic review2 has grouped into four broad types of effort:

- educational strategies

- financial incentives

- regulatory strategies

- personal and professional support.

Notably, this systematic review was only able to include one comparative study. This parallels the findings of a more recent systematic review of systematic reviews, which found only low-grade evidence among the nine included reviews to support some interventions3.

In Scotland, 17.8% of the population is classified as living in a rural area4. Some regions of the Scottish landmass are among the least densely populated areas in Europe, and 103 700 people live on 93 islands5. Scotland’s healthcare system includes six rural general hospitals (RGHs), which provide a full surgical service to the most remote and rural populations. The constraints of geography, finance and the needs of these populations dictate that local delivery of surgical services will continue to be required for the foreseeable future. The Scottish Government has committed to this provision, stating that, ‘access to healthcare should be as local as possible, for the whole population of Scotland, no matter where they live’6. Rural general surgeons provide most of the capacity required for a local surgical service, and often need to deploy an extended range of skills7,8.

Remote and rural surgery is formally recognised as a special interest area within the UK’s general surgery curriculum9, but this does not currently extend to a specific credentialling system. In recent years, recruitment and retention of rural general surgeons has become difficult, and RGHs have extensively relied on locums to maintain service cover7.

Any efforts to improve this situation in the UK require context-specific perspective on recruitment and retention challenges. This study aimed to assess the attitudes of current Scottish surgical trainees towards remote and rural surgery, with particular reference to their interest in training and working in rural environments, and the factors that influence this interest. The study also aimed to gather views from current trainees on how surgical jobs in Scotland’s RGHs might be made more attractive. No data of this nature are currently available in peer-reviewed literature.

Methods

Data collection

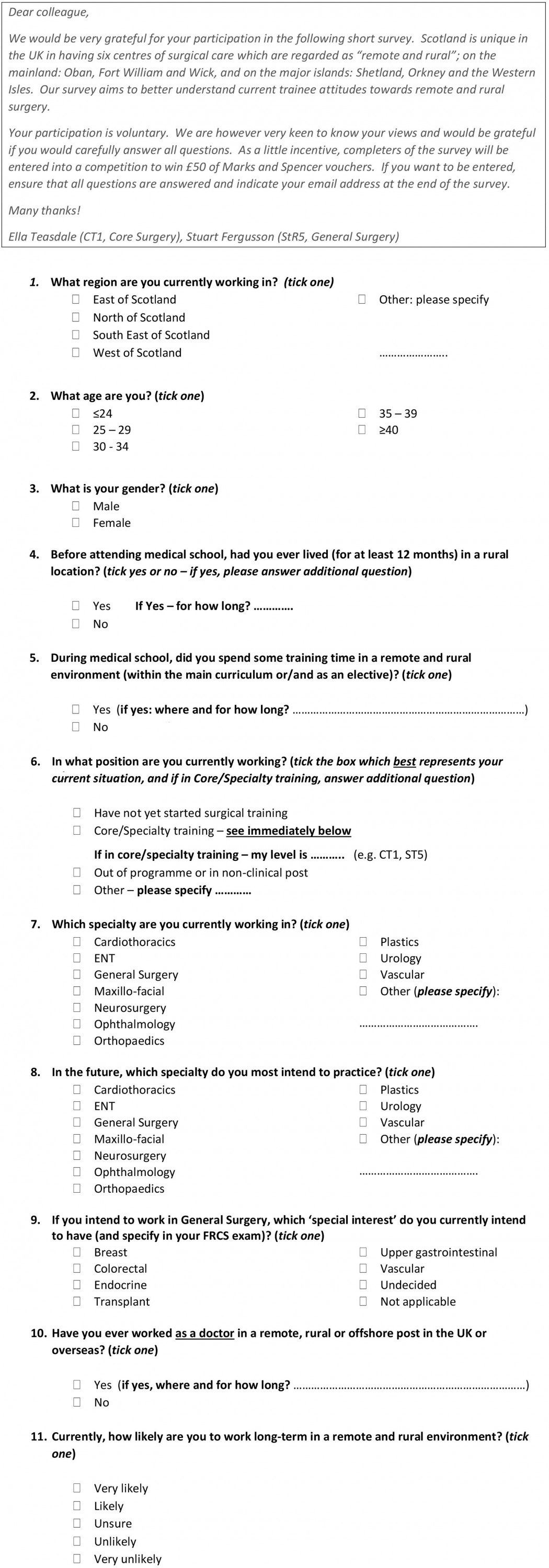

A survey was distributed to all Scottish core surgical trainees (n=95) and higher surgical trainees in general surgery (n=161) between July and September 2016. The survey was distributed in both paper and electronic forms.

In the UK, ‘core’ surgical training encompasses the first 2 years of the surgical curriculum, and ‘higher’ general surgical training encompasses years 3–8 of the curriculum. As of August 2021, core surgical training has been denoted phase 1, and higher surgical training in general surgery is split into an initial 4 years (phase 2) and a final 2 years (phase 3), with remote and rural surgery being an optional module in phase 29.

The survey was a novel 18-question instrument (Appendix I), which was designed by both authors to answer the study questions, drawing on data from previously published literature. Data were collected describing demographics, life and career experiences, and attitudes towards training and working in remote and rural environments. Given the anticipated heterogeneity of our cohort, Scotland’s six RGHs were listed in the survey introduction but a set definition of remote or rural was not provided.

The survey used a variety of categorical responses, including binomial and five-point Likert scale choices, and ranking questions. Ranking questions asked respondents to order the importance of potential barriers to both training and working in remote and rural hospitals, which had been identified as issues from previously published literature10, personal experience and discussion with Scottish remote and rural hospital practitioners. Free-text responses were invited on how remote and rural surgical jobs could be made more attractive. Participants were asked to only fill out the survey once.

The draft survey was reviewed by two subject experts for face validity and coverage of relevant issues. The survey was piloted individually by 10 junior doctors not undertaking surgical training, to check clarity and usability of the instrument. Non-surgical junior doctors were asked, to avoid potential contamination or reduction in size of the study sample.

Data analysis

Data were described and compared as appropriate to type and distribution. For univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, interest in training in a remote and rural environment was analysed as a binomial variable by combining ‘interested’ and ‘very interested’ ratings from the original five-point scale and comparing with other combined ratings. Perceived likelihood of working long term in a remote and rural environment was also analysed as a binomial variable by combining ‘likely’ and ‘very likely’ ratings in comparison with others. This contraction of data from a five-point to a two-point scale was undertaken to improve statistical power and clarity of result.

Analysis of ranking questions was performed using a weighted averages approach; the lowest ranking was assigned a score of 1, the next lowest ranking was assigned a score of 2, and so on. The score for each item was averaged out by the number of respondents ranking that item, meaning that higher weighted average scores indicated a higher preference for that item.

Statistical analyses were carried out using R v3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://www.r-project.org). Thematic analysis was undertaken on free-text responses. Not all surveys were fully completed; in such cases pairwise deletion was used rather than imputing missing data11. This approach was taken as the authors made an assumption that this data was ‘missing at random’, and constituted a small proportion of the dataset – for example, in the key question of how likely respondents were to work in a rural location, this data was missing in only 6 of 152 survey responses (4%).

Ethics approval

Formal National Health Service (NHS) Research Ethics Committee approval was not required for this study, since it was a non-interventional attitudinal assessment of NHS staff. However, written permission for this study was obtained from all relevant training program directors in Scotland, who assisted in survey dissemination.

Results

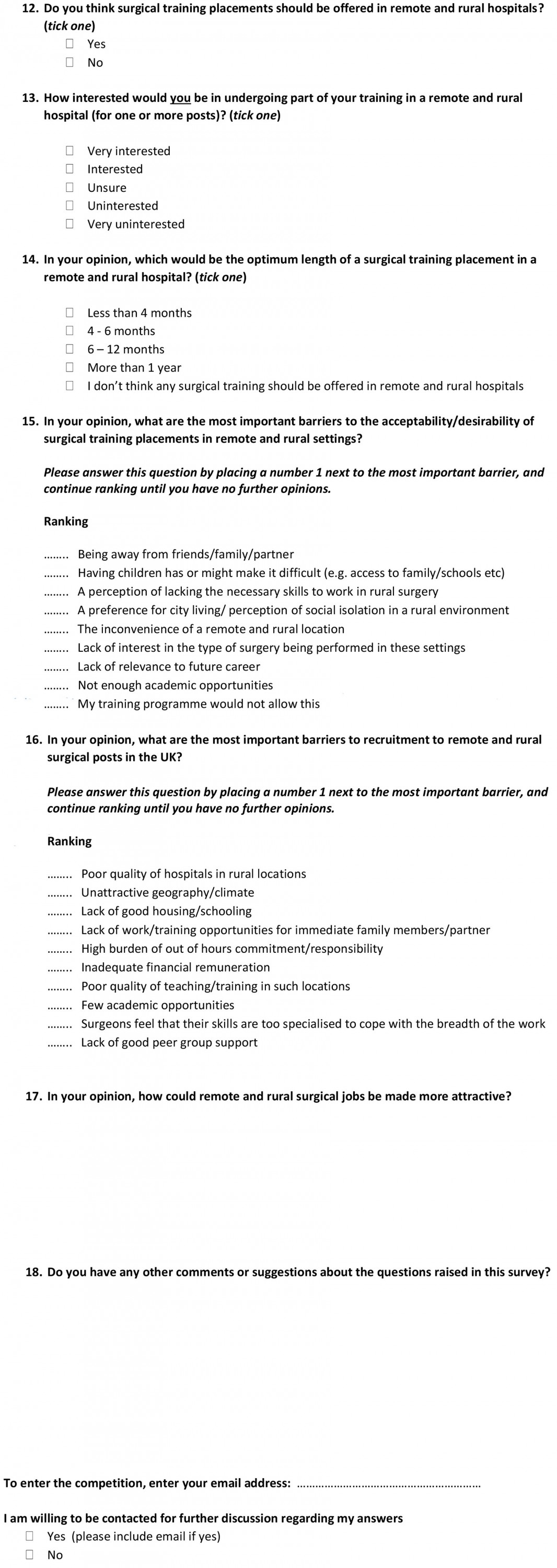

A total of 152 participants completed the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 59.4%. Survey cohort characteristics are reported in Table 1. The proportion of the cohort who had ever lived in a rural location (for 12 months or more) before medical school was 25.7%, while 31.6% of the cohort had received some undergraduate medical training in a rural location and 27.0% had personal experience of working as a doctor in a remote, rural or offshore post – in the UK or elsewhere.

Table 1: Cohort characteristics for surgical trainees completing the questionnaire (n=152)

Attitudes towards training in rural general hospitals

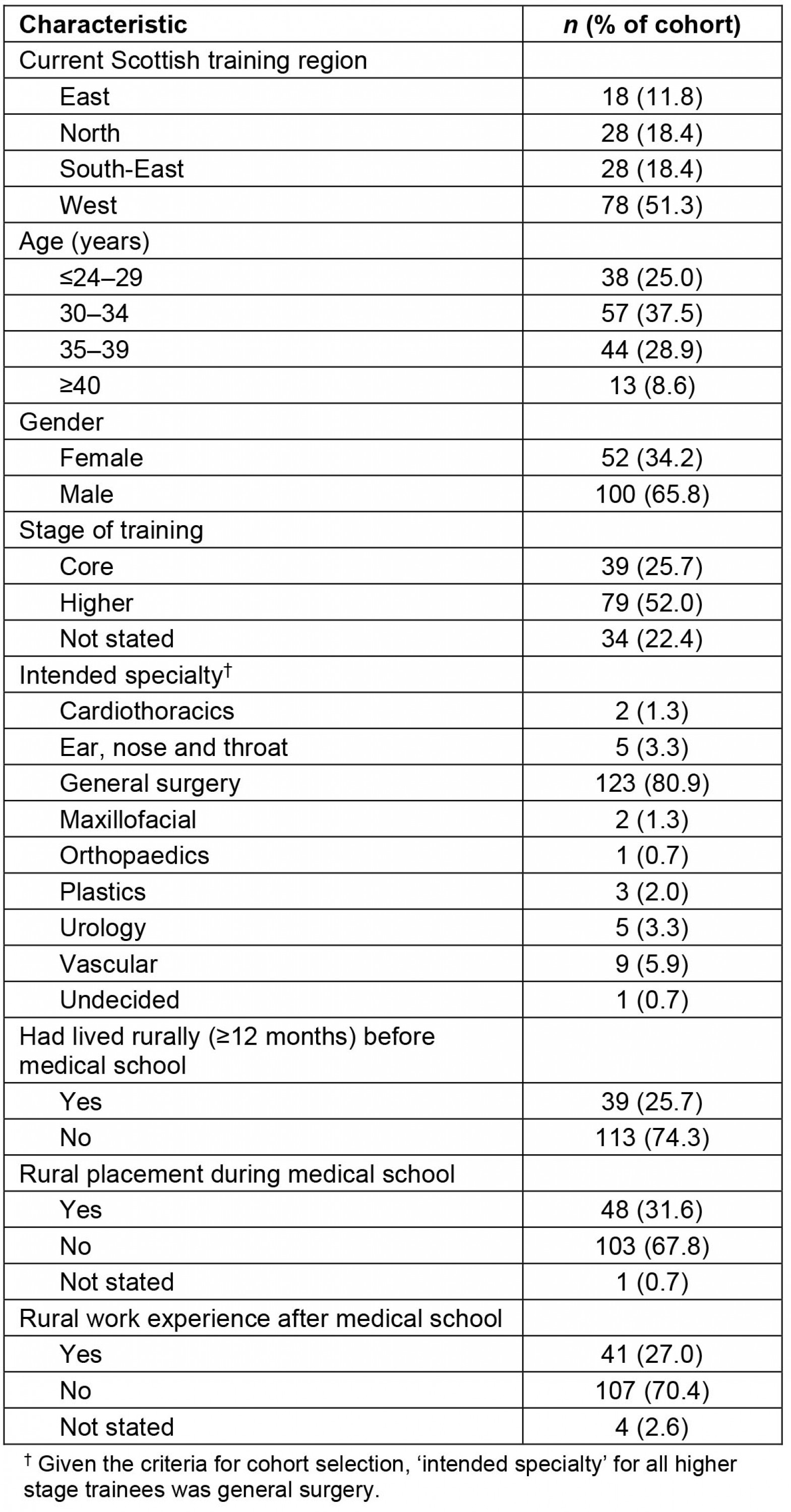

The large majority (80.9%) of respondents were of the opinion that surgical training placements should be offered in RGHs. The proportion of the cohort who were either ‘interested’ or ‘very interested’ personally in a rural surgical placement was 43.4%. Table 2 indicates participant opinions on the optimal length of an RGH placement. The most common response was ‘4–6 months’ (43.4%), with 90.4% of respondents selecting time scales of a year or less.

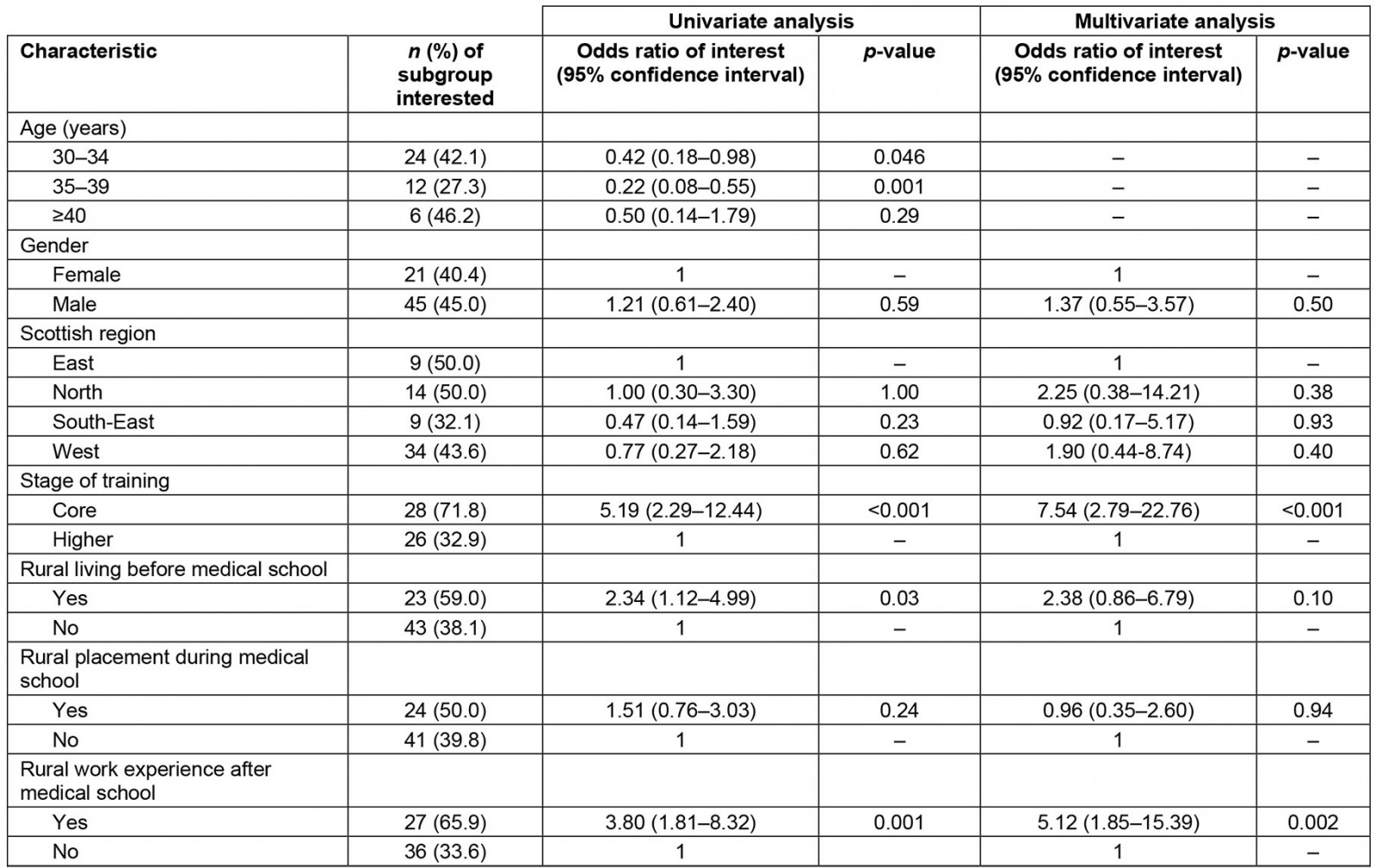

The potential effect of different cohort characteristics on interest in training in remote and rural environments was explored through univariate and multivariate analysis, with results shown in Table 3. On univariate analysis, the factors significantly associated with an interest in training in a RGH were younger age, being at the earlier (core) stage of training, living in a rural location before medical school, and rural work experience following medical school. On the final multivariate analysis, two factors remained significantly associated with an interest in rural training: being at the earlier (core) stage of training and having experience of working in a remote or rural location after medical school. Age was excluded from the final multivariate analysis model since inclusion of this variable created problematic collinearity effects.

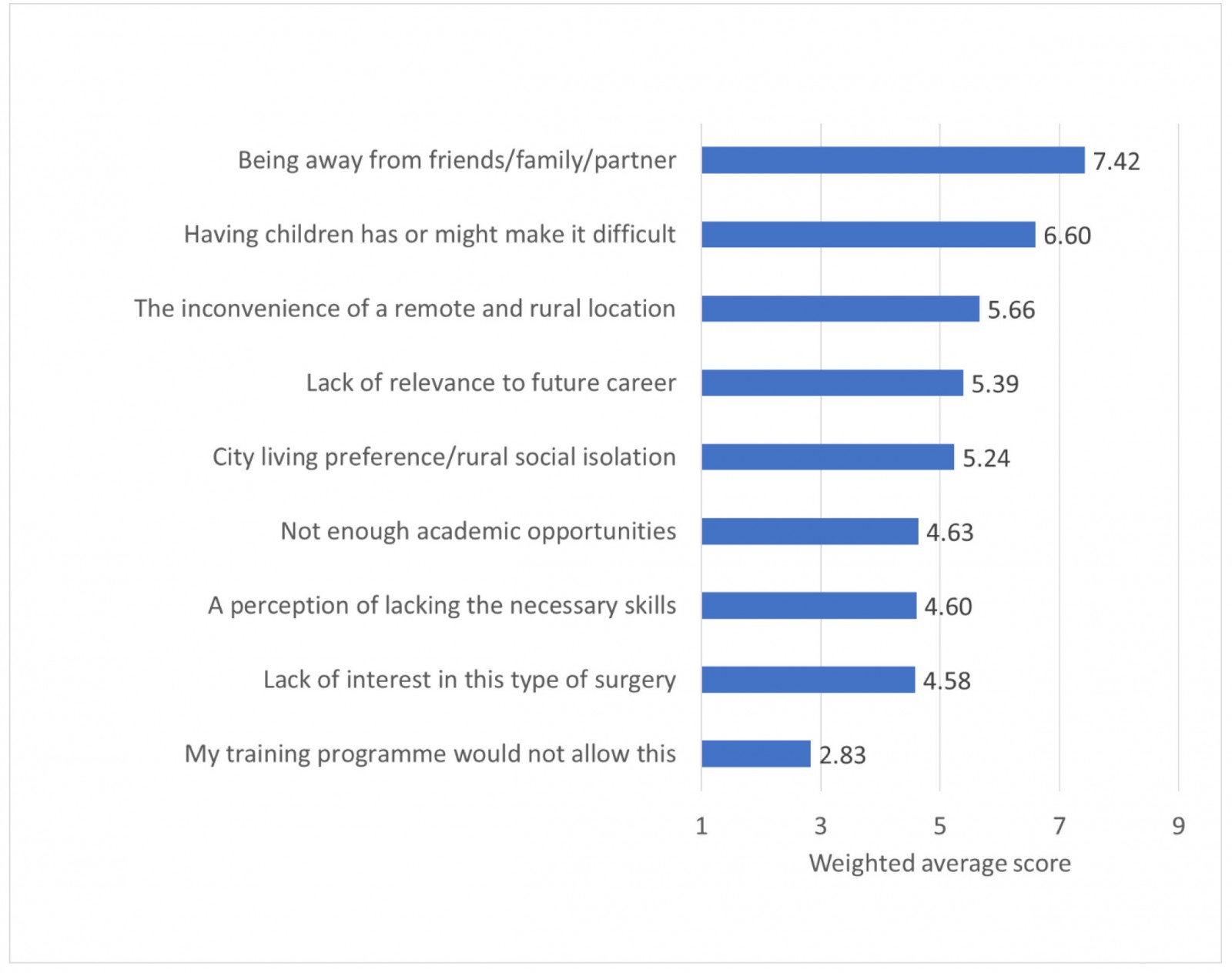

Results of an analysis of pre-identified perceived barriers to training in a remote and rural hospital (ranked in order of importance by each respondent) are shown in Figure 1. The weighted average score illustrates the degree of prioritisation that each item received. The potential barrier ranked as most important was ‘being away from friends/family/partner’. The next most-prioritised barriers were ‘having children would/might make it difficult’ and ‘the inconvenience of a remote and rural location’.

Table 2: Participant opinion on the optimum length of a rural general hospital placement

Table 3: Interest in training in rural general hospitals: univariate and multivariate analysis

Figure 1: Perceived barriers to training in a rural general hospital: weighted average analysis

Figure 1: Perceived barriers to training in a rural general hospital: weighted average analysis

Attitudes towards long-term working in rural general hospitals

Respondents were asked to rate how likely they were to personally work long term in a remote and rural environment, and a total of 14 respondents (9.2%) rated themselves either ‘likely’ or ‘very likely.’ Twenty-nine respondents (19.1%) were ‘unsure’ and the remainder were ‘unlikely’ or ‘very unlikely’.

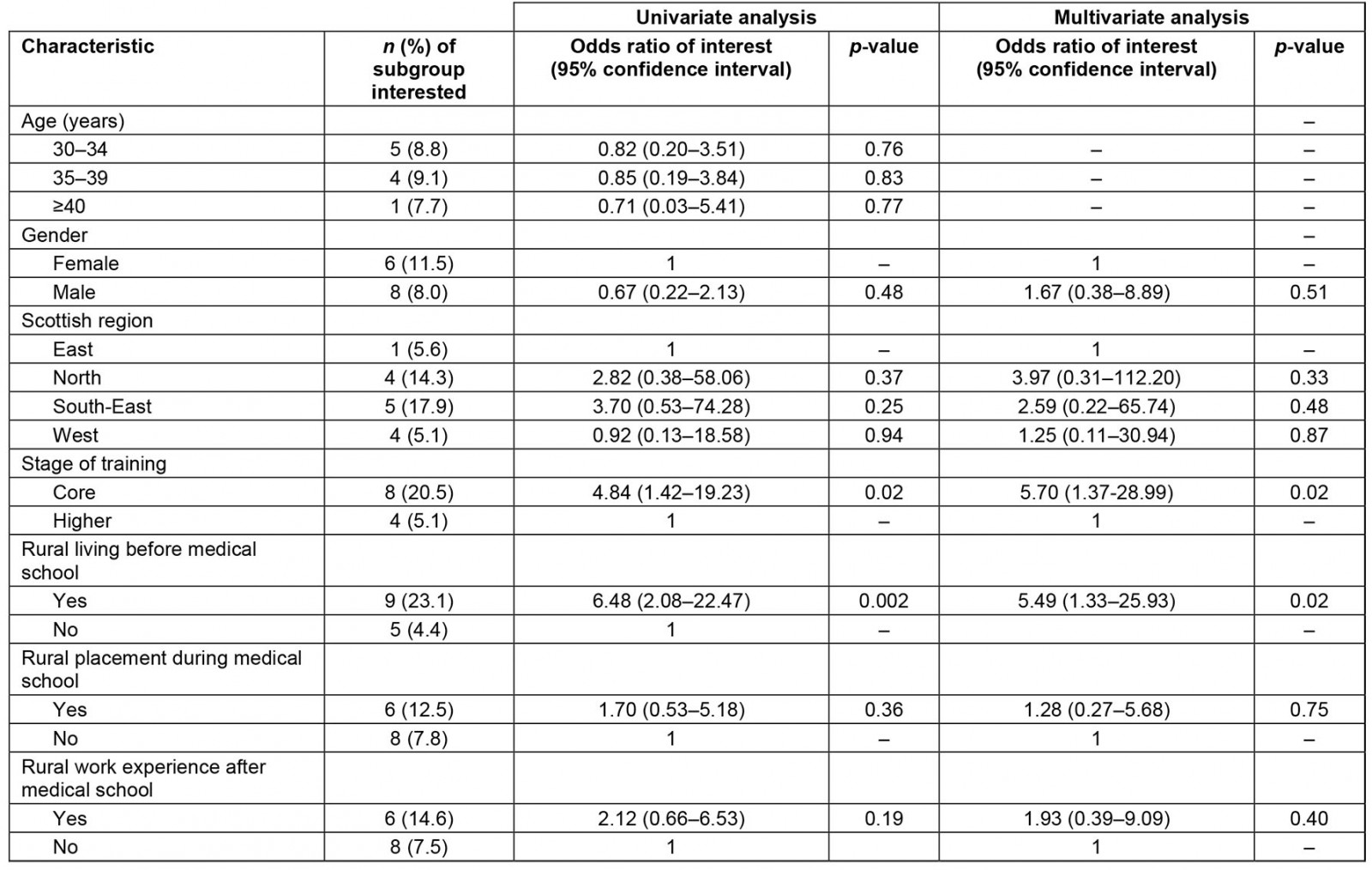

Results of univariate and multivariate analyses of variables potentially affecting long-term interest in a rural surgical career are shown in Table 4. On univariate analysis, the only two factors associated with an interest in a rural surgical career were being at the earlier (core) stage of surgical training, and having lived for at least 12 months in a rural location before entering medical school. This remained the case in a multivariate analysis. Age was excluded from the final multivariate model as inclusion caused problematic collinearity effects, as with the multivariate model of training interest (Table 3).

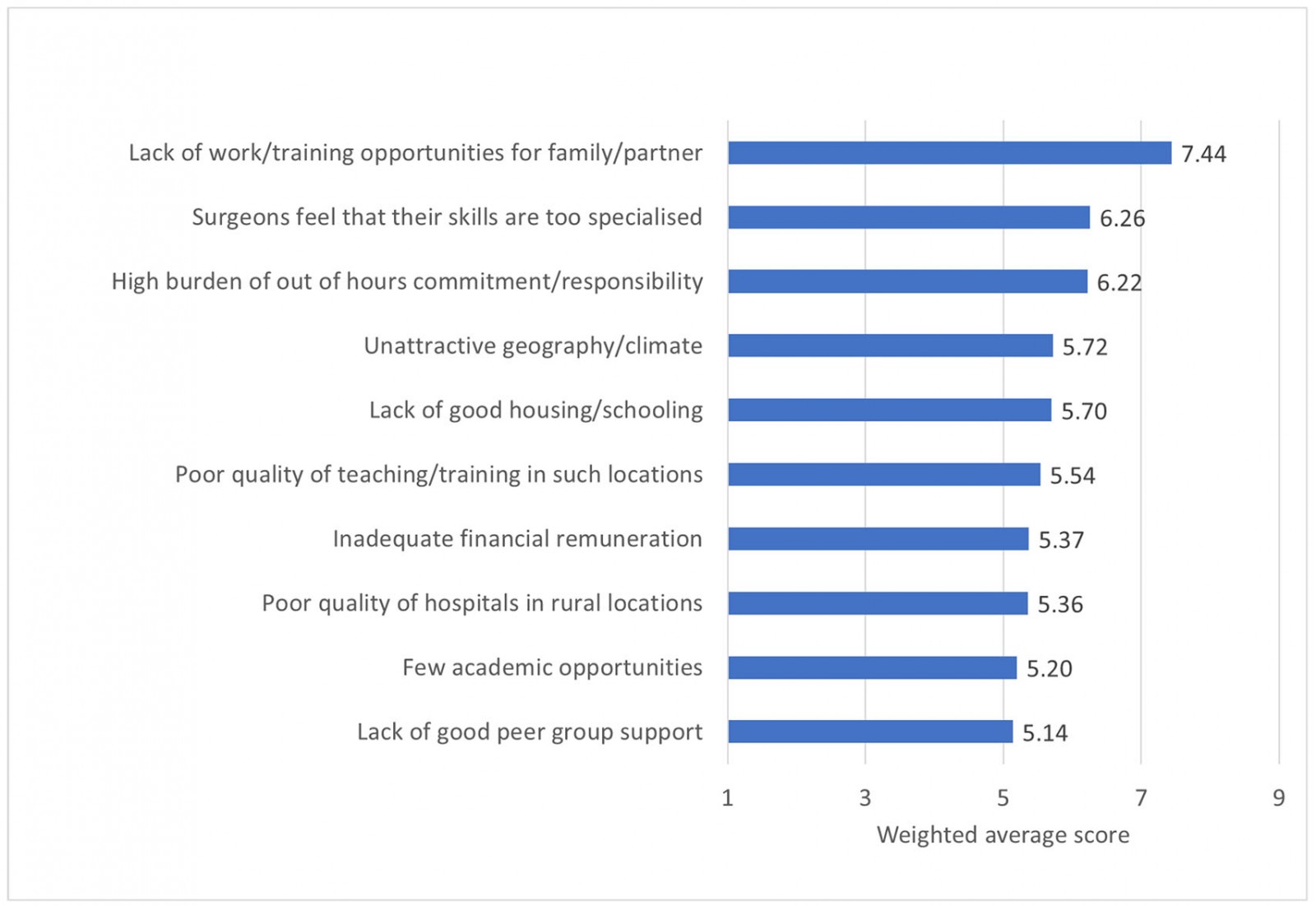

The ranking of pre-selected potential barriers to remote and rural surgery recruitment was also analysed using a weighted average score (Fig2). The barrier given highest prominence by trainee respondents was ‘lack of work/opportunities for family/partner’, with the next most important barriers ranked as ‘surgeons feel that their skills are too specialised’, and ‘high burden of out-of-hours commitment/responsibility’.

Table 4: Interest in long-term work in a rural general hospital: univariate and multivariate analysis

Figure 2: Perceived barriers to remote and rural surgical recruitment: weighted average analysis

Figure 2: Perceived barriers to remote and rural surgical recruitment: weighted average analysis

Improving the attractiveness of rural general hospital surgical jobs

Free-text responses were invited on how to improve the attractiveness of remote and rural surgical jobs, which were analysed thematically. The following themes were identified:

- increasing and improving training opportunities in rural hospitals

- increasing the breadth of surgical training

- optimising links with referral centres

- improving pay and conditions.

Increasing and improving training opportunities in rural hospitals: Some respondents were of the opinion that the attraction of rural surgical jobs could be improved by better highlighting and improving training opportunities in these locations. Comments included:

By having people go as a trainee, they would see it’s a really good work-life balance/lifestyle etc.

It’s not something I had really heard about until coming to this region so advertising/publicity could be improved.

One respondent gave the opinion that training placements in remote and rural hospitals gave:

scope for breadth of experience in assessment and initial management, but lack of specialists mean trainees do lose out.

A suggestion was given that:

pre-planned dedicated research/education projects [could] coincide with placement.

Increasing the breadth of surgical training: A number of respondents wrote that improving the breadth of surgical training would increase the attractiveness of rural posts, corresponding with the high ranking given to the pre-selected recruitment barrier ‘surgeons feel that their skills are too specialised’ (Fig2). A suggestion which typifies these opinions was:

teach broader skills and discourage such early sub-specialisation.

Optimising links with referral centres: Some responses indicated that optimising links between RGHs and larger units elsewhere would alleviate some anxieties about being based in a rural location:

Links with big centres are vital, my worry would be being isolated with a difficult case with no one from whom to seek advice, i.e. what to do next peri-operatively.

One opinion was given that jobs that combine responsibilities between rural and urban locations may be attractive for some:

Split [job] with large DGH [District General Hospital]/tertiary centre e.g. elective in major centre, emergency in R&R [Remote and Rural], opportunity for R&R surgeons to maintain skills by operating in large centre.

Improving pay and conditions: Some suggestions on improving the attractiveness of rural surgical jobs centred around the pay and conditions in such locations, with the suggestion that some financial supplements may be required:

Rural allowance is important as surgeons are still expected to attend mandatory training and this is more difficult and expensive from rural locations.

Greater financial support towards rural training opportunities was also suggested:

There are excellent opportunities to be had in remote and rural locations with regards to operative and trauma exposure but having to pay for accommodation twice (and location) make it much less attractive.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Scottish surgical trainees support the provision of training placements in remote and rural hospitals (80.9% in favour), and 43.4% were personally interested in undertaking surgical training in this kind of environment. In an adjusted multivariate analysis, interest in training in an RGH was associated with being a core (early-stage) trainee, and having personal experience of working in a remote or rural location after medical school. Physical separation from family, friends or partner was seen as a key barrier to the acceptability or desirability of a rural training placement, and financial support towards additional costs of travel and accommodation was an incentive suggested by several trainees.

A small minority of current Scottish surgical trainees expressed an interest in being based in an RGH in the long term (9.2%). In an adjusted analysis, interest in long-term rural surgical work was associated with being a core trainee and living in a rural area before medical school. Barriers to long-term rural work given prominence by current surgical trainees include fears over lack of work or other opportunities for family or partners, concern about being over-specialised and of having a high burden of on-call commitment. Trainees outlined views on a variety of approaches that they felt may improve the attractiveness of rural surgical posts.

Strengths and limitations

This survey accessed the views of a high proportion of current surgical trainees in Scotland (response rate 59.4%). The opinions of surgeons training in this region are of particular interest since they would seem to be a key target of efforts to improve recruitment and retention in rural Scottish hospitals. Their views may be relevant to contexts where other healthcare providers are seeking to recruit generalists.

The main limitation of this study relates to its survey methodology. It is difficult to fully understand and interpret complex, context-bound attitudes and motivations without recourse to exploration in real time, such as in interviews or focus groups. Understanding of this topic area would be enhanced by a further study using one of these qualitative techniques. A survey was pragmatic in assessing views from a large and representative sample of current trainees, although non-responder bias could mean that the authors overstated interest in rural work.

The survey instrument was not formally validated. No validated questionnaires were available for the topic areas explored in this study. There is no single applicable standard for validation of questionnaires, although this is generally understood to include elements such as expert appraisal of the content and face validity of the instrument12. To some degree this was obtained in the present study through the use of two subject experts who reviewed the instrument prior to use. The refinement of questions would have ideally involved focus groups of surgeons but the authors did not think this necessary for the once-off broad assessment that this questionnaire provided, and it would have reduced the size of the subsequent cohort available to study, since these individuals would have had to be excluded from the study population.

Relation to existing knowledge: influences on interest in rural surgical practice

This is the first study in the UK setting that has focused on the views of surgical trainees towards training and working in rural environments, although closely parallel work has explored a similar group in the US context13.

In previous literature, life experience in a rural environment is the most consistent factor found to positively influence a rural career choice10. The largest study of this effect used an Australian longitudinal cohort study of 3156 general practitioners (GPs) and 2425 specialists14. The study found that this positive association was only seen for GPs where they had spent six or more childhood years in a rural location, and for hospital specialists an association was only seen where they had spent at least 11 childhood years living rurally. This strong association has prompted the instigation in some areas of medical school admission policies that favour recruitment from rural areas, with some success in increasing the numbers of graduates who enter rural practice15.

This study’s findings that ‘being away from friends/family/partner’ was the most prominent barrier to rural training experience, and that ‘lack of work/training opportunities for family/partner’ was the most prominent barrier to a rural career choice, fit with previous research. A survey of 190 Australian junior doctors found that the most important reason given for a practice location decision varied significantly between those who aspired to work in a rural location and those who wished to practice in an urban environment16. ‘Partner, family, friends’ was given as the top consideration to a location choice by 46% of junior doctors who wished to practice in an urban environment, but only 5.9% of those who wished for a rural practice. Spooner et al undertook a recent qualitative study of career decision-making amongst UK Foundation Year 2 doctors and provide some insights on these processes17. In their sample, aspirations towards a good work–life balance seemed foremost among the concerns of junior doctors making career choices.

Another barrier given prominence in this study was the perception among surgeons of having too specialised a skill set for rural practice, and this concern does not seem limited to UK experience. A survey of 64 Canadian general surgical residents in their final year of training found that while surgeons were confident with basic general surgery procedures, confidence was significantly lower for the variety of subspecialty procedures that are a strong feature of many rural surgical practices18.

The finding in this study that being at an early stage of training is strongly associated with higher interest in rural training and working is novel. Previous work has not demonstrated an association between age and rural practice19, although it has focused on actual practice location, rather than career aspirations. From the present study, it is not possible to elucidate why interest decreases in later-stage trainees, and this is worthy of further investigation.

Relation to existing knowledge: views on encouraging rural surgical practice

This study explored Scottish trainee views on how rural practice might be made more attractive. One approach taken in Scotland to improve equitability of health professional distribution has been to develop both short and extended undergraduate rural placements, which have evaluated well in the Scottish context20 although they have not yet been strongly associated with subsequent rural practice. In this study, undergraduate rural placements had an insignificant association with interest in rural work.

One suggestion made by respondents in this study was to carefully ensure that undergraduate and postgraduate rural experiences were of high quality. A qualitative study of Scottish trainees in remote and rural locations showed that the perceived educational quality of jobs was often high, but could be coloured by challenges such as social isolation, additional expenses and poor accommodation21. It may be that investment in alleviating financial disincentives to rural training experiences would be worthwhile.

Some trainees suggested that the possibility of modifying conventional general surgical training towards a broader-based experience would help improve the appeal of rural practice. In the USA, some training programs have focused on producing broadly trained, rural-capable surgeons for many years, but there has still arguably been a lack of coordinated effort towards this goal22. An Australian rural training scheme was shown to be largely successful in preparing surgeons for this type of work, although the majority of scheme participants ultimately practised their careers in urban centres23. The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons now has a multi-point strategy towards rural surgical equity, with one new development being a system of dual accreditation in both a primary specialty and ‘Global Remote/Rural/Regional and Deployable (GRiD) Surgery’24.

Scotland has developed a Rural Surgical Fellowship scheme, for those at the end of general surgery training or beyond who wish to broaden their surgical experience in preparation for a rural surgical consultant position. Fellows are given bespoke, supernumerary access to specialties such as obstetrics and gynaecology, orthopaedics and urology. There would appear to be scope to increase awareness and uptake of this opportunity.

Another avenue of investment could be in increasing the number of surgical trainees who have postgraduate exposure to remote and rural surgery. A recent report by the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) suggested that as part of a strategy towards improved recruitment, ‘a 4- or 6-month rotation to a rural surgical unit should be offered to all general surgical trainees in Scotland’25. The study found that 43.4% of Scottish surgical trainees would be personally interested in a rural placement, although currently only three of Scotland’s six rural general hospitals provide placements to doctors in a surgical training program.

The same report by RCSEd recommended that rural surgeons needed to receive generous time away from their rural base to attend relevant courses and conferences, and time in specialist referral units to refresh or learn surgical skills. One innovative approach subsequently taken in Scotland to increase the attractiveness of rural consultant jobs has been to offer a permanent ‘global citizenship’ contract, which incorporates time for regular international volunteering into commitments at the rural base hospital26. The effectiveness of this strategy is not yet known.

In high-income countries, coordinated national approaches to the challenge of rural healthcare provision are not consistently in evidence, and it is difficult to pick apart which recruitment and retention initiatives may be having an effect27,28. Few studies have focused on the specific challenges of surgical recruitment in rural areas, and similar patterns may be found in analogous healthcare settings. This study provides data that will inform future qualitative exploration of these issues in the Scottish context, and formation of strategies that need to be subject to rigorous scrutiny.

Conclusion

Although surgeons may constitute a relatively small number of rural healthcare practitioners, the service they provide is key in maintaining the viability of RGHs29 and thus rural communities30. The continuation of full surgical services in RGHs has the strong backing of the Scottish Government6. Acute surgical workforce shortages in rural environments must therefore be addressed as a matter of national priority. This study’s findings contribute towards an understanding of how this might be done.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of surgical training program personnel throughout Scotland who assisted in dissemination of our questionnaire. We are also grateful to Mr David Sedgwick and Mr Gordon McFarlane for providing an expert (rural surgeon) review of the draft survey. We thank Professor Ronald MacVicar and Mr Sedgwick for providing helpful feedback on the draft manuscript.