Introduction

A large body of published evidence has emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic, and there is a lot more learning to be undertaken as the pandemic continues1,2.

Features of an island context

Optimising the management of COVID-19 is perhaps unique in an island context. Rural and island communities have different disease patterns compared to densely populated urban areas3. Population mortality rates appear to be highest in urban counties but case fatality rates appear to be higher in rural counties4. Climate and seasonal factors have also been shown to be key5. The flow of populations in and out of an island is particularly important, as is the extent to which visiting populations from areas that have a higher prevalence of COVID-19 mix with the local uninfected population6.

Operating in a political context

Public health evidence always operates in a wider political and cultural context, and the response to the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that. A recent article, discussing the extent to which evidence supported decision making during infectious disease outbreaks, recognised that ‘Decision makers … tend to be challenged by scientific uncertainties, which allow for conflicting interpretations of evidence and for public criticism and contestation of decision-making processes’7. Island communities often have to deal with local politics, as well as wider national political influences.

The modern world is built on extensive bureaucratic systems, from global players such as the World Health Organization to local systems including primary care and the local provision of social care. The interplay between these layers can be complex and challenging. This is perhaps particularly the case for atypical communities, such as island populations. The overall system can over- or under-amplify a range of factors. Barker argued that the response to the anticipated H1N1 pandemic in 2009 ‘led to a bureaucratic reflex, a security response event that overtook the present actualities of the disease’8. National responses therefore do not always align with the reality on the ground in island communities; for example, some island communities had no COVID-19 cases for long periods of time when COVID-19 rates were high in neighbouring mainland areas.

The key nature of communication and collaboration

Communication and access to information are often key, and the importance of the relationship between public health and the media, including social media, has been highlighted in some studies9. Island communities often have tight informal communication networks, which create a distinct common feature, which affects the public health response.

There was a recognition early in the pandemic that learning might be obtained by collaboration between public health teams across islands around Britain that took into account the unique characteristics of island life, and described and supported management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Professional isolation is a well recognised risk in rural and island communities, and the value of networks and related mechanisms to address personal and organisational development was recognised as having a clear evidence base10, from National Health Service (NHS) laboratory services11 to wider settings12. The present study drew on this evidence in terms of its design, focusing on the question ‘What are the key public health lessons that can be learned from the COVID-19 pandemic across island communities around Britain?’ The scope of the project has partly emerged through the project, but can be defined as focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic; covering the period January 2020 – June 2021; restricted to island communities around Britain; undertaken from a public health management perspective, with particular emphasis on health protection and the wider determinants of health; recognising the importance of preventing COVID-19 coming into an island, and controlling COVID-19 when and where it has appeared on an island; and recognising the unique aspects of island communities such as the impact of geography, travel and cultural factors.

Methods

A peer support group was set up to support island public health teams, and their Directors of Public Health (DPH) in particular, to share experiences and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The underlying paradigm was action learning, as expressed, for example, in the statement ‘Action research is simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out’13.

The group began as part of the North of Scotland Public Health Network and expanded from the north of Scotland health boards to include public health teams covering islands around Britain that could only be accessed by a boat or plane. One purpose of the group was to identify the differences and similarities in responses and approaches to COVID-19, draw together common threads, gather learning and understand how successful actions might be transferable.

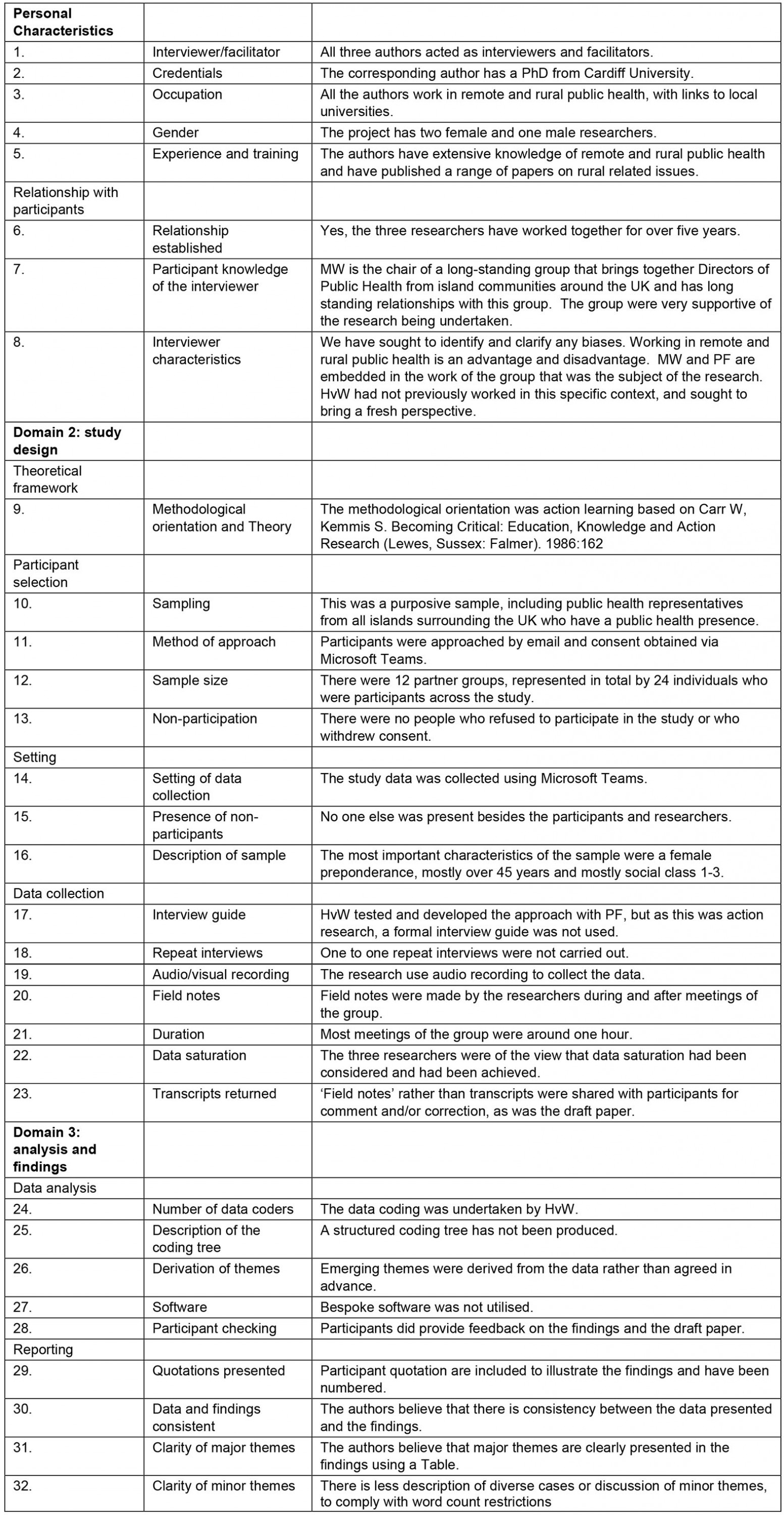

The learning of the group was captured through interviews with key leads in the group, analysis of two sets of independent notes (MW, PF) taken from the series of meetings of the peer support group, and thematic analysis of a recording of the final meeting reported within this article. Analysis was based on nine peer support meetings held at intervals of 6–8 weeks between 1 May 2020 and 21 June 2021. The membership of the peer support group was purposively drawn from DPHs covering British islands and Crown Dependencies around the UK, supplemented by colleagues in health protection or who had a key role in providing a public health response to COVID-19, particularly in those islands where there was no locally based DPH. Thematic analysis was begun by PF and developed further by HvW. Thematic analysis was undertaken manually rather than using computer software. A comparison of the methods used against the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) is provided in Supplementary table 114.

Ethics approval

This project was undertaken in line with the ethics principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and local governance policies and procedures. Every participant agreed to being part of the study and supported publication of the study.

Results

Island characteristics and legal frameworks

The included island communities have a range of different characteristics. Three of the island groups are Crown Dependencies with high levels of self-governance: Bailiwick of Jersey, Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Isle of Man. In these settings, public health was closely aligned to the government executive function and political system, and was supported by the capacity to rapidly enact legislation to address the specific needs of the island(s) at any given time. The nature of the Crown Dependencies was associated with greater autonomy, which allowed local decision making over the pace, rate and categories of testing regimes for COVID-19 that was generally seen as giving some tactical advantages to these jurisdictions.

Public health teams in the Isle of Wight and the Isles of Scilly sat within local government, as is the case throughout England. In these islands, public health management arrangements were jointly undertaken with mainland local authorities, which provided access to larger public health teams, creating greater resilience.

Public health teams in Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles are under NHS Health Boards, which are specific to each island community. This facilitated communication and influence with local health services, but each team was relatively small, so significant outbreaks on each island stretched the available resources tremendously. Archipelagos of inhabited islands are found in a number of Scottish health boards. Some of these islands did not have a doctor or nurse living on the island, which has led to challenges in assessing or testing potential COVID-19 patients, particularly as travel on and off islands was restricted.

Some Scottish islands come under mainland health boards, particularly NHS Highland, which has 27 inhabited islands. NHS Ayrshire and Arran includes two islands (Arran and Great Cumbrae) with small hospitals.

Size and local infrastructure

There was variability among islands in access to hospital care. Larger islands or island groups have basic secondary care; smaller islands, such as the Scilly Isles or Arran, have general practitioner (GP)-led community hospitals. Even smaller islands have a visiting GP and nursing service. All the islands have some threshold at which acutely sick patients need transfer off the island. These transfers were challenging in the context of COVID-19 infection control requirements. It was also a challenge to get those who had required hospital treatment for COVID-19 off the island and back to their island home during and after their infectious period.

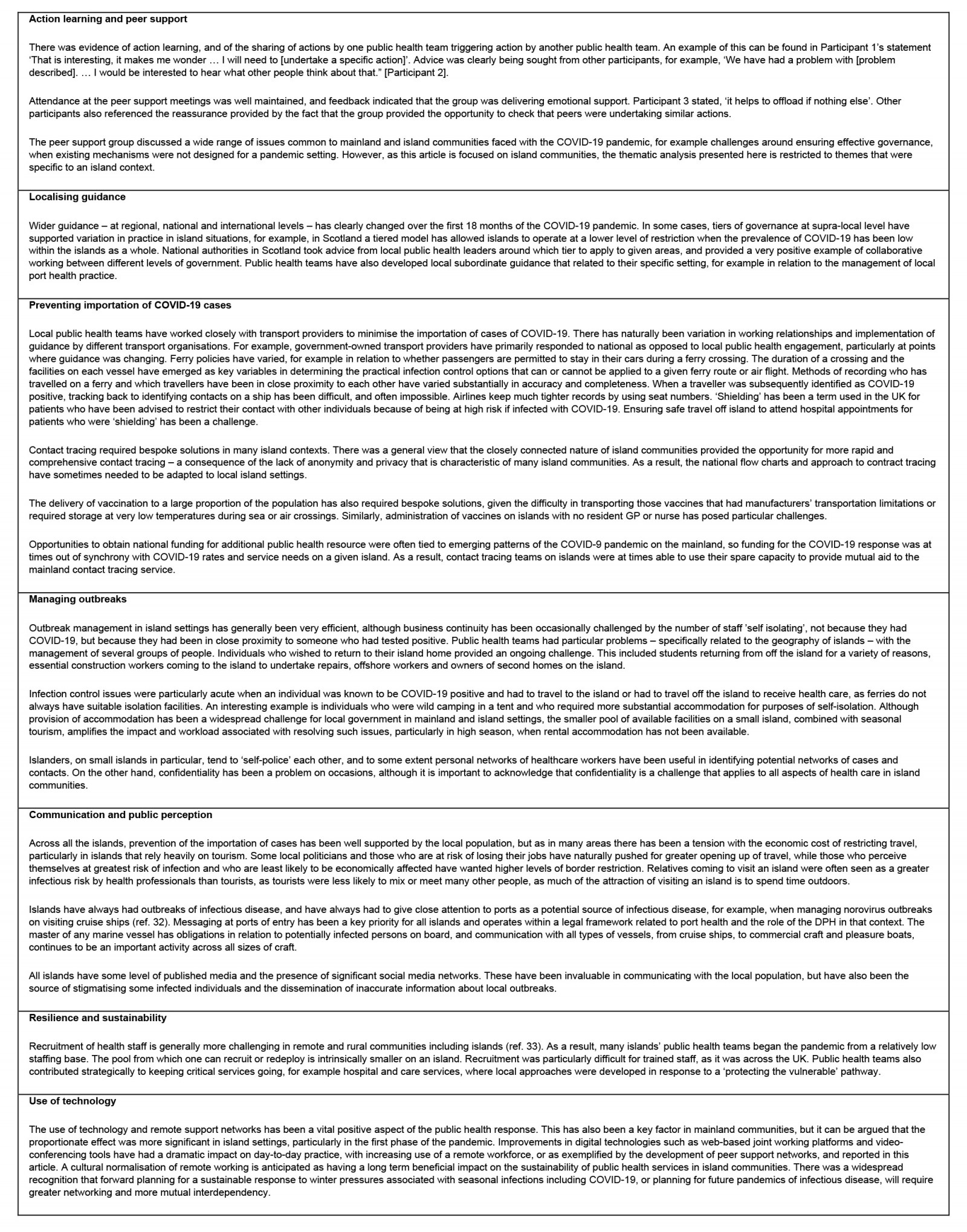

A detailed review of identified themes is provided in Table 1.

A common theme across the islands was the mix of long stretches of time with no COVID-19 infections at all, followed by rapid bursts of spread, requiring intense action when such outbreaks occurred. Although these outbreaks were small by most standards, they were often demanding to manage in terms of the available public health resource and other calls on local public health teams.

Table 1: Themes identified as important to the management of COVID-19 across the island public health teams15,16

Discussion

Analysis of the discourse within a public health peer support network across British island communities identified action learning in a number of areas including sharing local guidance, actions to prevent the importation of COVID-19, approaches to managing outbreaks, approaches to communication and public engagement, and strengthened resilience – and it has supported a future focus on enhancing sustainability.

Localising guidance

There are a huge variety of islands across the world and a number of papers examining different aspects of the relationship between health and living on an island, including theoretical models that examine this relationship. Telesford explored four features of islands in relation to COIVD-19: boundness, smallness, isolation and fragmentation17. He highlighted that an island ‘conjures a feeling of being trapped within geographical as well as psychological and societal boundaries, which contributes to a strong sense of attachment to one’s island’ and highlighted the relationship between this boundedness and the risk of isolation. He also pointed out that, on the other hand, ‘no island stands alone’ and that connectivity is a key feature of all island communities. In the context of COVID-19, the article highlighted the tension between using border control to reduce the importation of COVID-19 versus the adverse economic impact of such measures. All the factors raised in Telesford’s article were recognisable in our analysis of discussion within the peer support group across the British islands.

Border control is a key topic in the literature regarding COVID-19 in an island context, and the potential economic impact associated with tight border control is a key challenge. A study in the Pacific islands concludes, ‘Efforts to prevent transmission by closing borders reduced transmission but also created significant economic hardship’18. The problem is a significant one, even for much larger islands such as New Zealand19.

The impact of COVID-19 control measures has so far been mitigated to a great extent in the British Isles as a result of a generous government funded package, which has been accessible to most of the individuals who have been unable to work as a result of lockdown measures. The extent to which islands will use tight border control to limit the importation of COVID-19 is likely to be a key area of policy decision for island communities in the future.

Preventing importation of COVID-19

A recent article explored the development of an objective tool to assess the impact of air travel in a Pacific Island context, and there may be the possibility of developing a similar approach for other jurisdictions. The risk model was based on six categories20:

(i) ‘prevention’ (i.e. prevention of the emergence or release of pathogens); (ii) ‘detection and reporting’ (i.e. early detection and reporting for epidemics of potential international concern); (iii) ‘rapid response’ (i.e. rapid response to and mitigation of the spread of an epidemic); (iv) ‘health system’ (sufficient and robust health system to treat the sick and protect health workers); (v) ‘compliance with international norms’ (i.e. commitments to improving national capacity, financing plans to address gaps and adhering to global norms) and (vi) ‘risk environment’ (i.e. overall risk environment and country vulnerability to biological threats).

Managing outbreaks

Several articles have explored aspects of outbreak control in island settings. A review of Caribbean island approaches referenced border controls, as has already been referred to. The article also references control of movement on an island, and control of gatherings21. The management of COVID-19 in a number of British Overseas Territories not included in our peer support group concluded that outbreaks had been effectively managed in these contexts, but that relationships with the UK Government were at times strained, due to a perceived neocolonial attitude and what was viewed in at least one case as ‘misleading information’20.

Peer support for an ‘action learning’ approach

Better relationships than those reported in the Caribbean experience20 were generally experienced by members of our group. Several areas in the UK had tiered responses, depending on the prevalence of COVID-19 in a particular area. In a Scottish context, some of the restrictions in the different levels had unintended consequences for island communities. For example, when areas were classed as Level 1, there was no indoor visiting in homes, whereas on the mainland it was possible to meet up in a coffee shop, an option not available to many islanders. For mental wellbeing reasons, Directors of Public Health agreed with national authorities that visiting in homes would be allowed on such islands. In other cases, there was at times a sense that the particular characteristics of a given island were not always fully understood by central authorities.

Communication and public perception

Island communities often rely on visiting external expert skills to sustain complex infrastructure, such as servicing a CT scanner in a small island hospital. Islands also depend on imported foods and other goods. The management of this flow of personnel has been complicated by the pandemic. Detailed analysis of the impact of some of these factors has been undertaken on specific islands, for example, Shetland22.

There are many other aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic communication that could have been explored in our study, including a more in-depth analysis of the role of the press and social media. A recent review of island ferry travel and tourism, in the context of COVID-19 in Hong Kong, found significant fluctuation over time in online searches related to tourism in a given context, which probably reflected changes in local prevalence and policy23.

Use of technology

Social media has provided a contentious space during the pandemic, with both helpful information and misinformation appearing and widely shared24,25. There is a lot still to learn about optimal communication in the context of a pandemic. Some social platforms have removed posts that they considered inaccurate or misinformation, but some authors argue that the basis for such assessment may at times have be conflated with political processes26,27.

Resilience and sustainability

Resilience and long term sustainability of island communities is important, particularly in relation to potential climate change impacts28,29. However, there has also been criticism that much of the literature is not written by those who live on potentially affected islands and that there has at times between a failure to recognise how resilient and adaptable island communities can be30. One positive outcome that may emerge across islands as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic is a greater desire to maximise internal sustainability, for example greater use of locally grown food, resulting in a reduced reliance on external supply chains31.

Conclusion

There are distinct characteristics of public health practice in island communities, and the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted these. The key action learnings that have come out of this study include the importance of border control to minimise the importation of cases, rapid control of outbreaks when they occur, close cooperation with transport providers, and effective communication and engagement with local and visiting populations. A peer support group was effective in providing mutual support and shared learning across quite varied island contexts. There was a sense that this had helped in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic and facilitated in maintaining a low prevalence of infection.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve and it is clear that further action learning will be needed to mitigate the impact of the pandemic, balance economic and service needs, and manage the flow of individuals in and out of an island. There are ongoing research opportunities. For example, pre- and post-travel testing has played a role in minimising spread and it may be possible to utilise new rapid salivary tests at ports of entry in a way that is particularly useful to island communities32,33.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following individuals who were key members of the project steering group: Christina Morrison (NHS Western Isles); Tim Allison and Jenny Wares (NHS Highland); Louise Wilson, Rebecca Welfare and Sara Lewis (NHS Orkney); Susan Webb and Susan Laidlaw (NHS Shetland); Allan Penman and Tristan Hamade (NHS Ayrshire and Arran); Simon Bryant and Robert Pears (Hampshire and Isle of Wight); Rachel Wigglesworth, Aisling Khan, Ruth Goldstein, Abigail Wrigley and Faye Colcoff (Cornwall and Isles of Scilly); Nicola Brink (Guernsey, Alderney and Sark); Ivan Muscat and Cynthia Folarin (Jersey); and Henrietta Ewart and Jacqui Dunn (Isle of Man).