Introduction

According to the WHO, more than 2 billion cases of diarrheal disease are reported globally each year, which result in more than 2 million annual deaths1,2. Diarrheal disease affects children aged less than 5 years disproportionately2: in Latin America alone, diarrheal disease causes more than 75 000 annual deaths in children aged less than 5 years3,4. Diarrheal disease also has numerous chronic consequences in children, such as decreased growth, undernutrition, and impaired cognitive development2-6.

Inadequate access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) are known risk factors for diarrheal disease3,5-7. Nevertheless, WASH infrastructure is inequitably distributed worldwide and remains a global health challenge6,8-10. More than 40% of the global population experiences water scarcity, and even among those who do have access to water, approximately 23% (1.8 billion) use a fecally contaminated drinking water source2,11-14. Furthermore, in 2015, only 39% of the global population had access to safe sanitation services (eg toilets and latrines)6,8-10. These unsafe water and hygiene conditions are responsible for nearly 90% of diarrheal deaths globally, and the health impacts of investment in WASH interventions are well documented13-15. Importantly, it is anticipated that climate change will compound these existing human health risks via degradation of freshwater sources and impacts on water security16,17. In some regions of the Amazon, populations are already reporting challenges with water security due to increasing flooding18.

Although Peru was very successful in achieving the 2015 Millennium Development Goal (MDG) indicators for water access, it was not as successful for sanitation14,19-21. The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which build upon the MDGs, include an enhanced focus on access to quality water, sustainable sanitation, and ending open defecation (SDG6)10,11. Furthermore, the SDGs have a pledge to ‘leave no one behind’, and countries have committed to prioritizing marginalized populations, including children, women, and Indigenous Peoples18,22. Consequently, the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme created SDG-indicators in water access, sanitation, and hygiene to help identify populations that should be prioritized to meet national SDG targets14. Current policies in Peru for Drinking Water and Sanitation include Programa Nacional de Saneamiento Rural (National Sanitation Rural Program), which aims to supply water and sanitation to communities from the four basins in the Peruvian Amazon that are home to several Indigenous Amazonian communities. Additionally, the Ministry of Housing conducts the PIASAR – Programa Integral de agua y saneamiento rural (Rural Global Water and Sanitation Program), which has collaboration and support from the Inter-American Development Bank.

Previous studies conducted in Peru have revealed a high prevalence of diarrhea in children aged less than 5 years, particularly in rural and remote areas23,24. Of note, one study in the Peruvian Amazon reported a prevalence of diarrhea as high as 50% for Indigenous children25. Given the previously reported high burden of diarrheal disease among Indigenous children in Peru, as well as the ambitious and regionally targeted focus of the SDGs, it is critical to understand current WASH indicators in Indigenous communities in Peru in order to identify and prioritize public health interventions18,26. As such, this study aimed to estimate the prevalence of childhood diarrhea, characterize access to water and sanitation, and determine the association of childhood diarrhea with water access and sanitation indicators in 10 Shawi Indigenous communities along the Armanayacu River in the Peruvian Amazon.

Methods

Shawi Indigenous Peoples

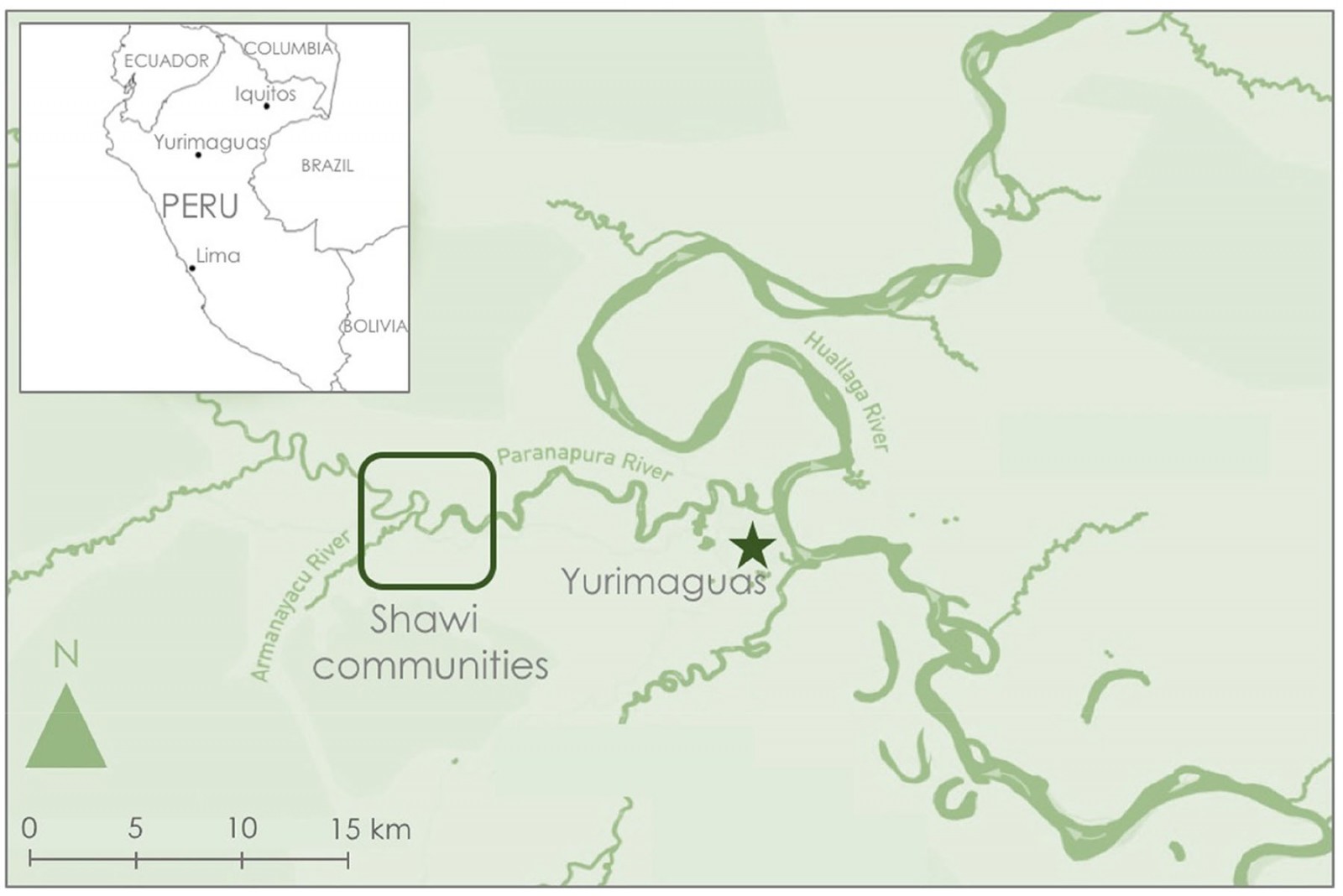

Shawi Indigenous Peoples predominantly reside in the province of Alto Amazonas in the department of Loreto within the Peruvian Amazon (Fig1). With a population of about 25 000, Shawi are one of 55 Indigenous Peoples in Peru. Shawi maintain subsistence livelihoods, relying on hunting, local agriculture, fishing, and local drinks like masato (a fermented beverage made from cassava) as key food sources. Shawi culture is rich and vibrant, with strong connections to the environment27. The Peruvian Amazon climate is generally warm and humid, with a rainy and a dry season. In recent years, communities have expressed concerns regarding increasing flooding, which is expected to be exacerbated by climate-related stresses and environmental degradation from deforestation and resource extraction28-30.

Research approach and study design

This research is embedded within a larger water and sanitation project31 part of the Indigenous Health Adaptation to Climate Change (IHACC) Program. EcoHealth principles guided the research approach, emphasizing transdisciplinarity, equity, participation, and sustainability in the research process32. Indigenous Shawi guided and contributed to all research phases, including study design, data collection, result interpretation, result dissemination, and co-authorship.

This study was conceptualized in collaboration with national, regional, and local Indigenous leaders and communities who provided input into research topics that would meaningfully benefit Indigenous Shawi communities33. These collaborators identified water security as one of the main climate-health outcomes of concern for Shawi peoples34.

Before the study was designed, researchers (PT, GL, CZ) visited 18 Shawi communities in the Balsapuerto district, of the province of Alto Amazonas (Fig1). Communities were selected on the basis of: interest in and availability for participating in data collection; having a large proportion of the population comprising children aged less than 5 years; and accessibility from the city of Yurimaguas (ie within a 2-hour drive and up to five additional hours on foot). Leaders from these communities co-developed the research objectives and methods and advised on several practical topics, including how to approach household members (eg following local gendered practices, males were the first person to contact) and when to visit communities. Community leaders also suggested hiring local research assistants. Ten of these 18 communities ultimately partnered in the study. At the request of the communities and for confidentiality purposes, community names are not used herein.

Data collection

A survey questionnaire was used to collect standardized data from households. The questionnaire was created in a workshop with local Shawi teachers where questions were co-developed and pre-tested for content, context, and language. The questionnaire was then piloted by Shawi researchers31. The questionnaire captured data on three focus areas of the IHACC Program: food security, vector-borne diseases, and water security. The outcome of interest in this study was diarrheal disease in children aged less than 5 years, as reported by a parent. Diarrheal disease was defined as at least one episode of diarrhea (ie three or more loose stools in a 24-hour period) in the month prior to survey35-37. Exposures of interest were water source, perceived water source quality, water treatment method, and type of sanitation facility. A global water access/sanitation score was calculated by assigning a 0 or a 1 to each of the exposures of interest, and then summing to obtain the final score. Scores ranged from 0 to 4, where a higher score reflected better access to safe water and sanitation. Sociodemographic variables and information on feeding practices were also captured to include as confounding variables. Nutritional status was assessed via physical examination of the participating child (ie weight, height/length) to provide context for diarrheal disease in the community, as outlined by Zavaleta et al38.

Data were collected during the rainy season of 2015 (November–December) by a team of eight trained local Shawi researchers. All households in participating communities with at least one child aged less than 5 years were invited to participate at a community assembly. If a household had more than one child aged less than 5 years, a single child was randomly selected to participate. The survey was completed at the household level, where at least one adult member, who was required to be older than 18 years and have resided in the community for at least the prior 6 months, responded to all survey questions. Each household decided who would answer on behalf of the children (ie mother or father or both). If both parents were absent at the time of the visit, and would not return in the next month, a grandparent was interviewed, as they are protectors and caregivers in Shawi culture31.

The survey was administered orally in the local Shawi language at each household. Responses were recorded in paper form. Nutritional examinations (ie weight, height/length) were performed in a second visit to the household by a non-Shawi nutritionist and nurse.

Data analysis

Data from the questionnaires were manually entered into an Excel database, then uploaded into Stata/SE v15.0 (StataCorp; https://www.stata.com/stata15) for data cleaning and statistical analyses. Monthly prevalence of childhood diarrhea was calculated. Nutritional calculations to assess for stunting and wasting were conducted using the igrowup_Stata package from the WHO Child Growth Standards39. Descriptive statistics were performed for each independent variable; means were reported with their standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact tests. Ordinal variables were compared using χ2 tests to examine linear trends. For comparisons between continuous variables, the student’s t or Wilcoxon tests were performed when required. Prevalence ratios (PRs) with their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. Power calculation was done post-hoc, allowing us to detect with at least 73% power, differences of 50% or larger in the prevalence rates of exposures of water and sanitation variables between cases and non-cases.

Ethics approval

The study protocol and instruments were reviewed and approved by the McGill University Research Ethics Board and by the Institutional Review Board at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (approval no. 59472). Shawi community leaders were extensively consulted before initiating the study to ensure agreement, collaboration, and understanding throughout the research process33,40,41. Informed consent was obtained from the community authorities and participating households.

Figure 1: Partnering Indigenous Shawi communities along the Armanayacu River, Yurimaguas, and surrounding area in the Loreto Region of the Peruvian Amazon. (Credit: Carleee Wright and Paola A. Torres-Slimming)

Figure 1: Partnering Indigenous Shawi communities along the Armanayacu River, Yurimaguas, and surrounding area in the Loreto Region of the Peruvian Amazon. (Credit: Carleee Wright and Paola A. Torres-Slimming)

Results

Response rate

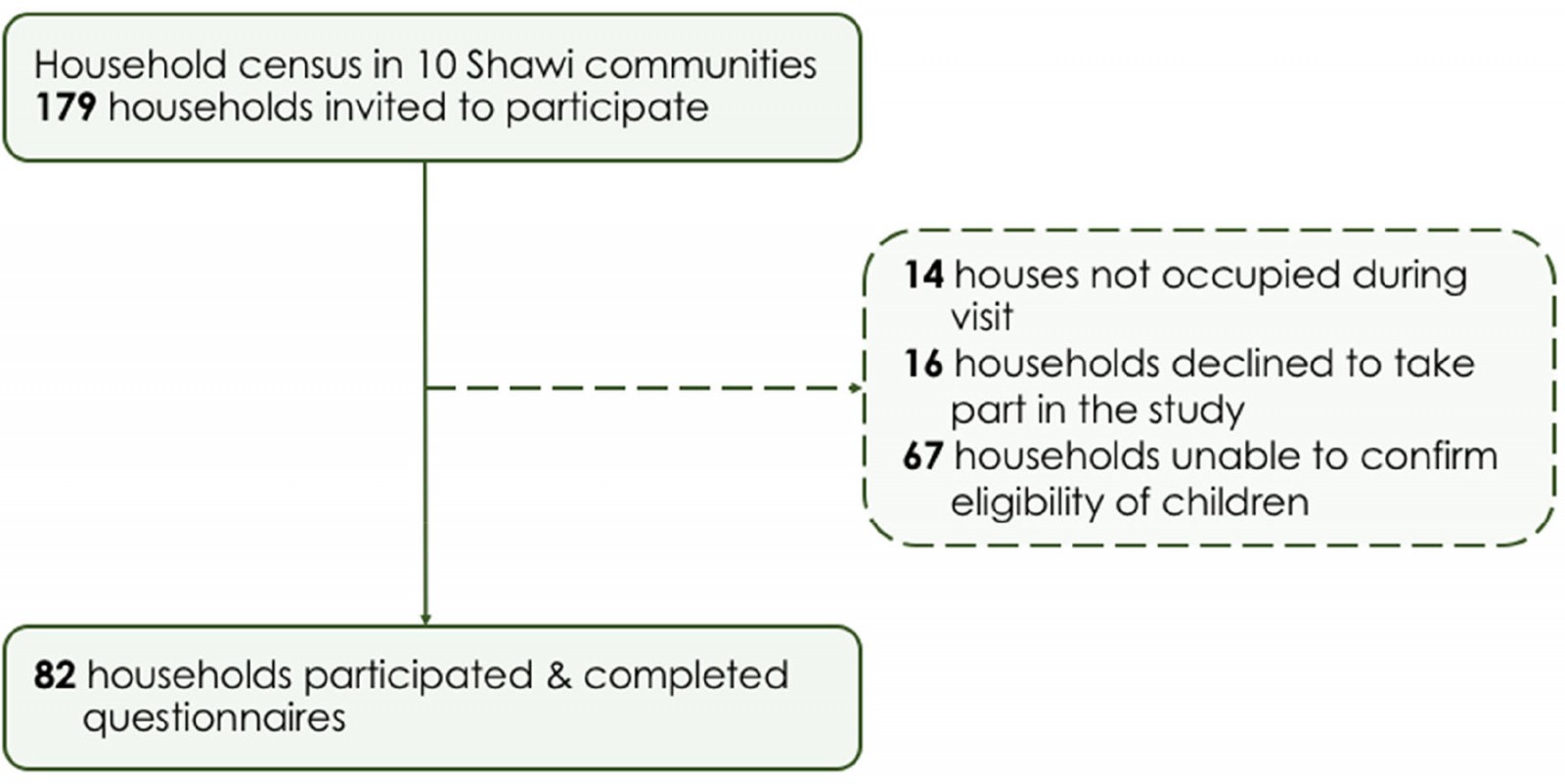

Of the 179 households identified, 14 (8%) were absent during the study period, 67 (37%) did not meet inclusion criteria (ie children in the house were older than 5 years), and 16 (9%) declined participation (Fig2). A total of 82 households agreed to participate. The number of participating households per community ranged from 1 to 22.

Sociodemographic data

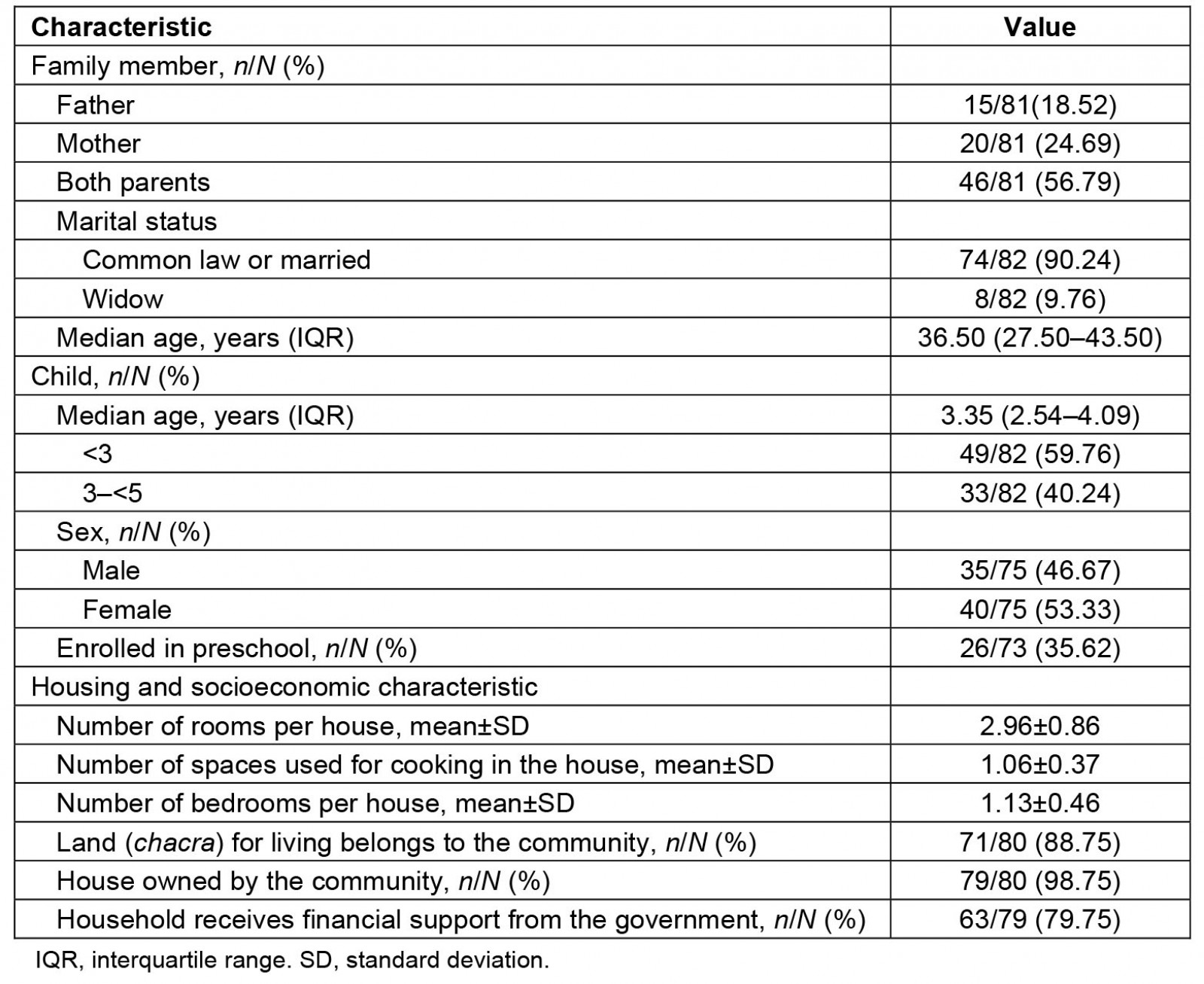

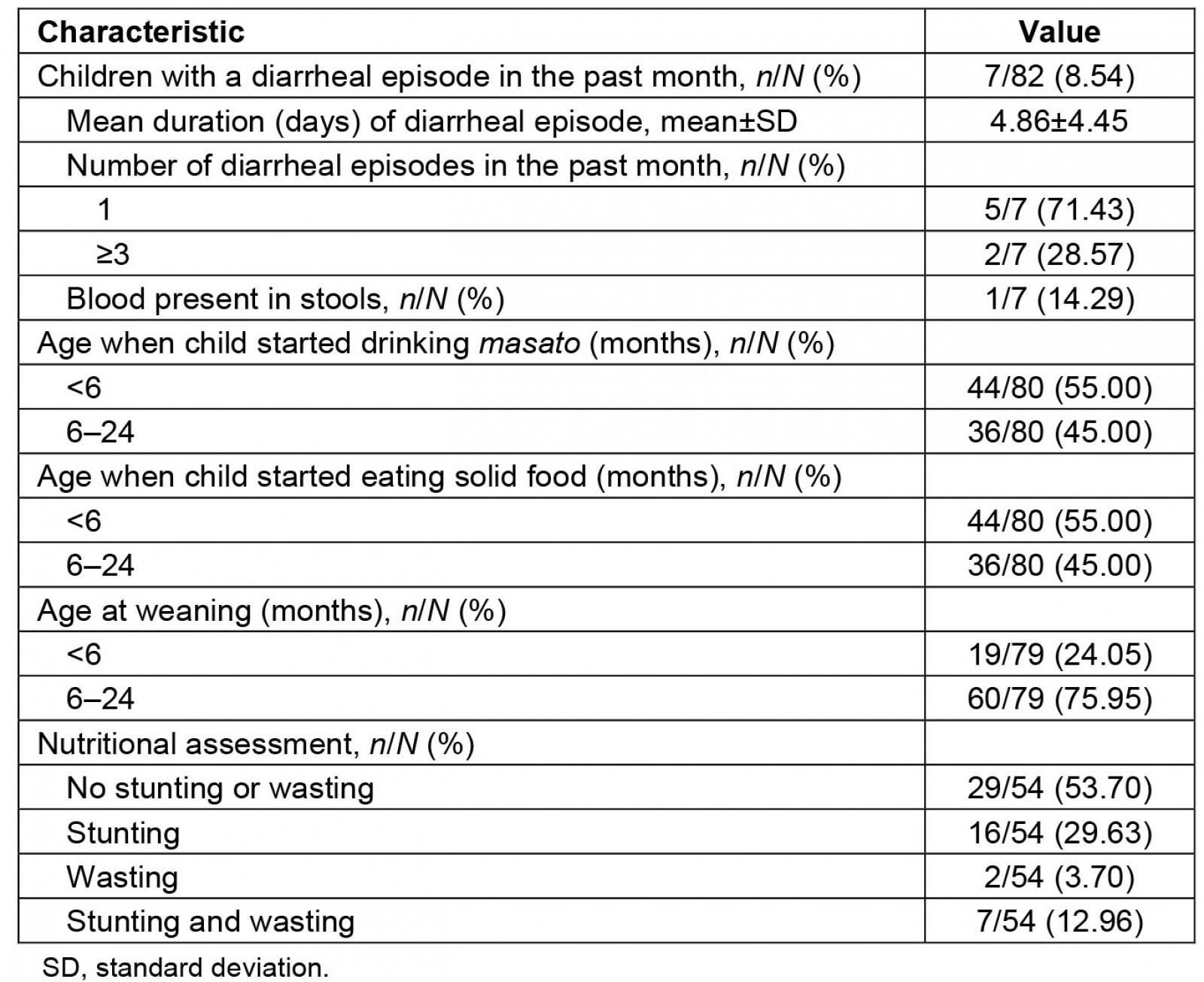

In 57% (n=46) of households, both parents responded on behalf of the child (Table 1). The median age of participating children was 3.35 years. Just over half (53%) of the children were female, and one-third attended preschool. Nutritional data were obtained from 66% (54/82) of children, of whom almost half had stunting, wasting, or both (Table 2). Almost all houses and family farms (chacra) were located on communal land (Fig3) and most households (80%) received economic support through a national cash transfer program. At 6 months of age, all children were eating solid food and many (55%) had started drinking masato. Most children (75%) were weaned after the age of 6 months (Table 2).

Diarrheal disease

Seven (9%) children, located across four of the 10 communities, had at least one episode of diarrhea in the month prior to the survey (location data not shown for confidentiality). The mean duration of diarrhea was 4.86 days. One case involved bloody stools.

Water access and sanitation

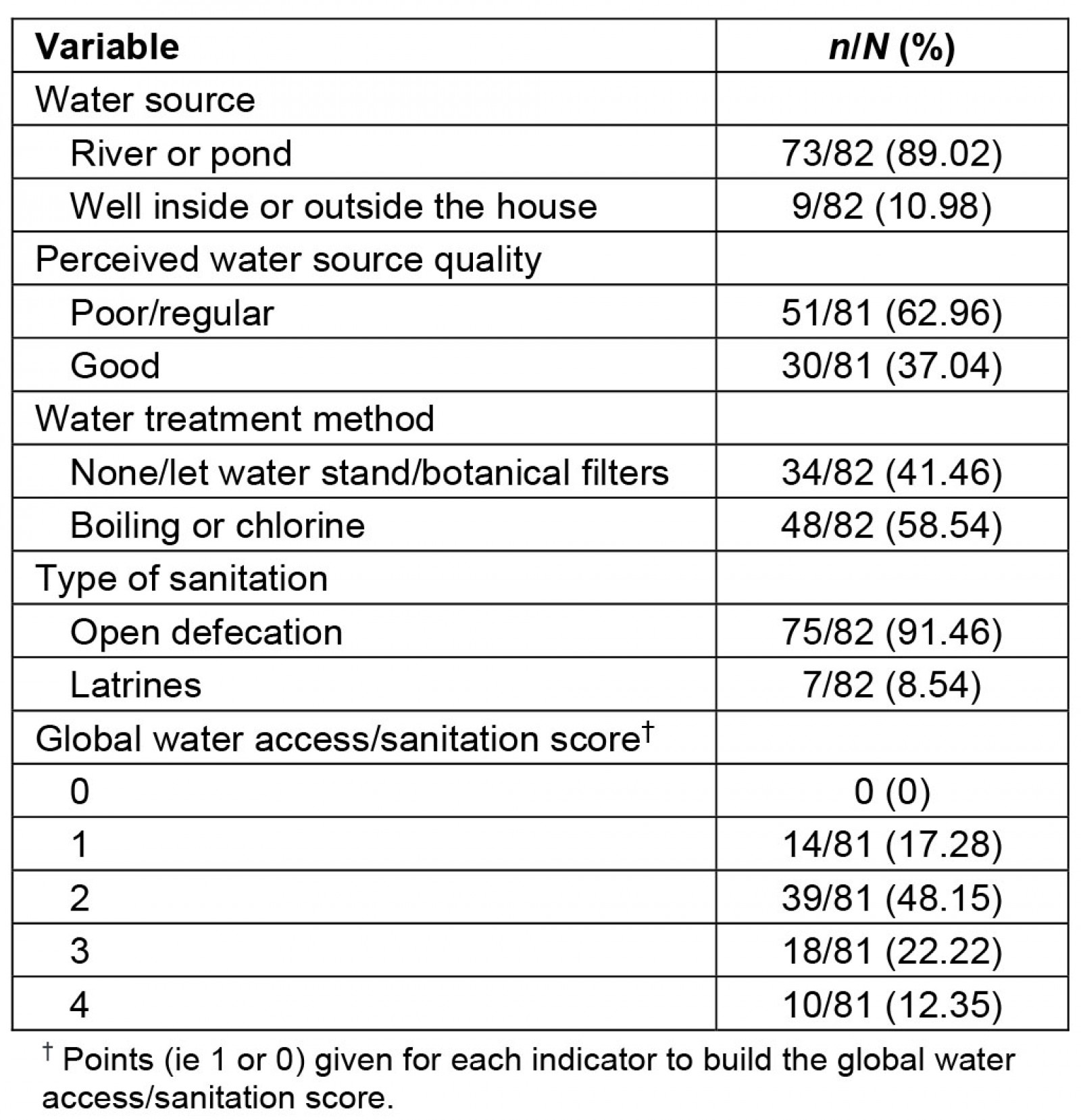

Most (89%) participants’ main water source was the Armanayacu River. Only 37% of participants described their water source’s smell, color, and taste to be ‘good quality’. Over 58% of respondents boiled or chlorinated their drinking water. Other water treatment methods included letting the water stand or filtering water with plants. The practice of open defecation was common (91%). Only two households used closed latrines, while five households used open latrines. The most common global water access/sanitation score was 2 (48%); no household had a score of 0 (Table 3).

Association between diarrheal disease and water and sanitation associations

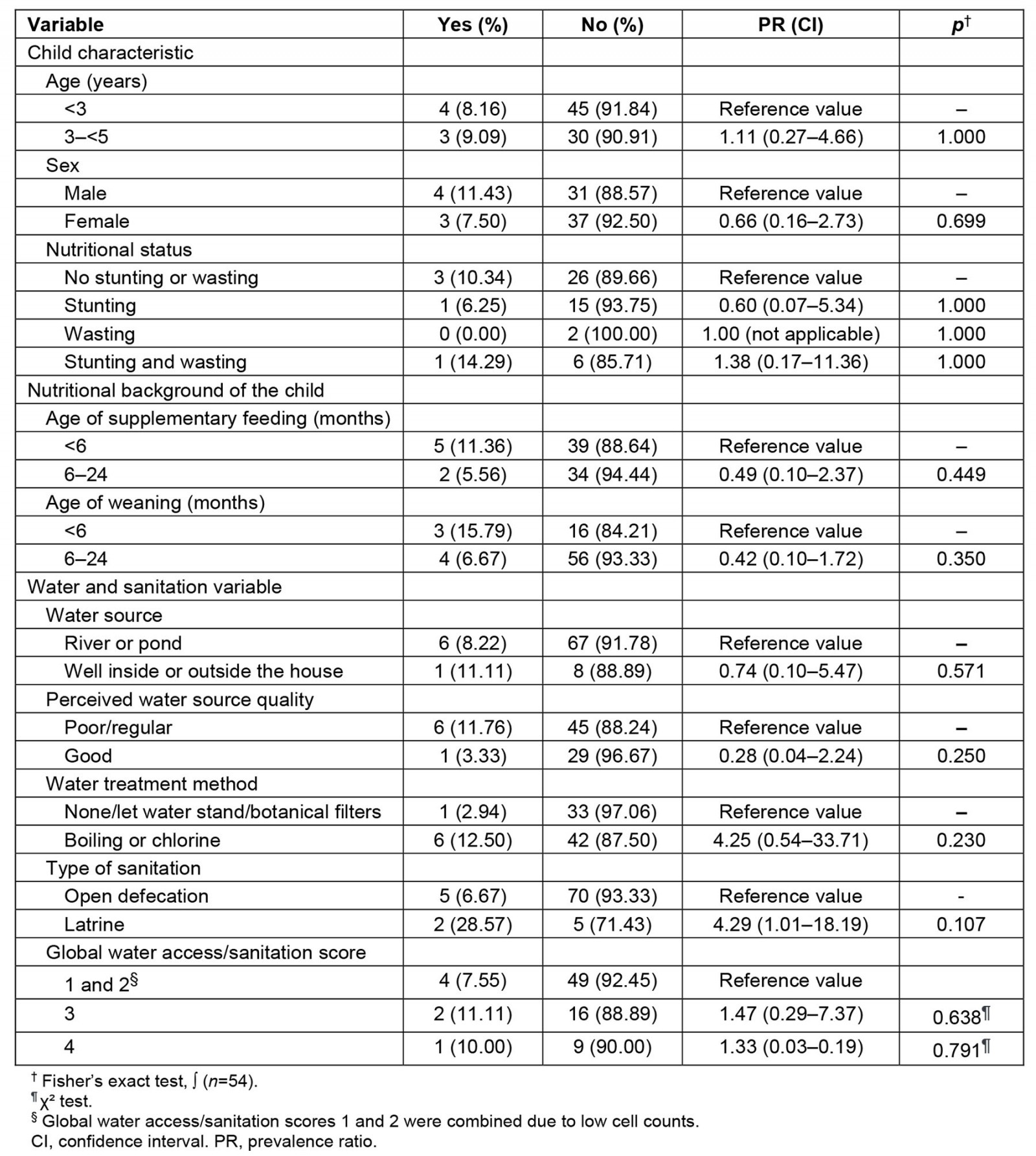

Children living in households that used latrines were 4.29 times more likely to report an episode of diarrhea in the prior month, compared to households that practiced open defecation (PR 4.29, 95%CI 1.01–18.19, p=0.107) (Table 4). Similarly, although not statistically significant, children in households that boiled or chlorinated their water were 4.25 times more likely to report an episode of diarrhea in the prior month than those who did not (PR 4.25, 95%CI 0.54–33.71, p=0.230) (Table 4). Water source, perceived water quality, and the final global water access/sanitation score had no significant association with childhood diarrhea in the prior month. Confounding variables, including sex, age, and feeding practices, were not statistically significant. Child nutritional status was not significantly associated with diarrheal disease in the prior month (p=1.000).

Table 1: Household sociodemographic characteristics of survey participants in 10 Shawi communities, Peruvian Amazon (n=82 participants)

Table 2: Description of diarrheal episodes and nutritional history of children in 10 Indigenous Shawi communities, Peruvian Amazon

Table 3: Water access and sanitation indicators in 10 Indigenous Shawi communities, Peruvian Amazon (n=82 participants)

Table 4: Associations of a child experiencing diarrhea in the last month with water, sanitation, nutrition, and demographic variables for 10 Shawi communities in the Peruvian Amazon (n=82 participants)

Figure 2: Response rate for household survey in 10 Indigenous Shawi communities in the Peruvian Amazon.

Figure 2: Response rate for household survey in 10 Indigenous Shawi communities in the Peruvian Amazon.

Figure 3: An example of sanitation facilities.

Figure 3: An example of sanitation facilities.

Discussion

This study explored the association of diarrheal disease and water access and sanitation indicators in children aged less than 5 years in 10 Shawi Indigenous communities. The diarrheal disease period prevalence for children aged less than 5 years was 8.54%, which is lower than national data and studies conducted in other Amazonian communities24,27,42,43. This finding could be explained by the season that the survey was conducted in: this cross-sectional study was carried out during the rainy season when diarrhea rates can be lower, because in the dry season, lower rainfall can decrease water flows and concentrate fecal coliforms44,45. Furthermore, Shawi’s consumption of masato, a beverage made from fermented cassava46, could help explain this finding, as although masato consumption was not significantly associated with diarrhea in our study, masato has been found to reduce microbial contamination of untreated water, and thus may be protective against water-related diarrheal disease46.

While not statistically significant, a finding of this study was that households that used water treatment methods had higher rates of childhood diarrheal disease than those that did not. As McClelland et al suggest, inadequate effects of point-of-use water treatment prior to consumption could potentially recontaminate water sources47. Therefore, this may be explained by the fact that those using untreated water are consuming it as masato46,48. Future studies should investigate local risk and protective factors against childhood diarrheal disease.

While not statistically significant, the PR of childhood diarrhea in this study was 4.29 times higher in households that used latrines than in households that practiced open defecation. This finding does not align with other global studies, where the implementation of latrines has consistently reduced diarrheal disease prevalence15,49-52. Inconsistent latrine use may have contributed to this unexpected finding15. One of the reasons in the failure of successful sanitation indicators is considering whether to install toilets if there is no perceived demand by the population53. Hence, as Mara mentions, cultural local preferences should be explored before locating any sanitation infrastructure54. Failures related to sanitation strategies can include inadequate location and the odor removal system55,56. A study done in rural Caribbean areas in Colombia by Galezzo et al concluded that in order to reduce childhood diarrheal, prevalence policies need to incorporate environmental and sanitation strategies within households57; our study also points to the importance of engaging communities to develop culturally appropriate sanitation interventions.

Importantly, this study was conducted in the rainy season, during which flooding is an increased risk28-30. Flooding negatively affects sanitation infrastructure, particularly pit latrines, which pose a high risk of overflow during flooding periods, thus contributing to increased risk of diarrheal disease34,58-62. Data relating to frequency of latrine use as well as recent precipitation and/or flooding events were not collected in this study, precluding analysis of these potential risk factors58. However, given this unexpected finding, further investigation is warranted. This is particularly important in the context of climate change in the western Amazon, where increased rainfall and flooding due to extreme weather events are projected62-66. Furthermore, disaggregating the type of latrine (pit versus raised pit) used in these communities would be important because raised pit latrines are recognized as a more suitable sanitation system in flood-prone areas and should be considered in future WASH interventions59-61.

In these 10 Shawi communities, drinking water was accessed directly through the Armanayacu River and the practice of open defecation was common. Based on these indicators, the Shawi communities scored in the bottom ‘ladder’ of the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for progress towards the SDG goals for access to safe water and sanitation14,66. Although since 2005 the Peruvian government has implemented a National Rural Program for Drinking Water and Sanitation, which aims to supply water and sanitation to communities from the four basins in the Peruvian Amazon, there is no evidence of their presence in the Armanayacu river basin. Consequently, these communities must be prioritized in upcoming SDG WASH initiatives13,15,65-68. In order to maximize the effectiveness of WASH initiatives, decision-makers must identify, understand, and incorporate local Indigenous values and cultural practices into intervention design and implementation58,67-77. Without such consideration, studies show that community uptake of WASH interventions will be limited25,27,78-82.

Strengths and limitations

As a cross-sectional study, the statistical associations presented cannot be used to infer a cause-and-effect relationship. The attempted household census was a strength of this study; however, the small sample size precluded multivariable analysis and adjustment for clustering within community and for nutritional status. Recall bias is also a general limitation of retrospective survey methods; however, similar methods have previously been successful in this region.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study conducted in 10 Indigenous Shawi communities provides valuable information about childhood diarrheal disease and related water and sanitation risk factors, which can serve to inform efforts to meet the SDGs in Peru. The prevalence of childhood diarrhea was lower than that reported in other areas of the Amazon. Given this result, and the unexpected findings of higher rates of childhood diarrhea in households that used latrines and water treatment methods than in those that did not, further investigation into local risk and protective factors for childhood diarrhea is needed. Furthermore, these communities scored in the bottom ‘ladder’ of the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme, meaning that they must be prioritized in future WASH initiatives. Research will be required to understand and incorporate local Indigenous values and cultural practices into WASH initiatives to maximize intervention uptake and effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all Shawi community members for participating in this study. Special thanks to Tito Chanchari, Elvis Lancha, and Desiderio Tangoa for their assistance with data collection.

Statement of funding

This research was supported by the IHACC Program through funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the International Development Research Centre’s International Research Initiative on Adaptation to Climate Change. Funding was also provided by a 2016 Ekosanté Internship Award, a 2015 UNESCO/Keizo Obuchi Research Fellowship, and a 2014 Ekosanté Professional Development Award. The funders did not play a role in study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript writing; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

You might also be interested in:

2018 - Promoting delayed umbilical cord clamping: an educational intervention in a rural hospital