Introduction

In general practice, technical procedures have many areas of application, including prevention (eg vaccination or cervical smear), diagnosis (eg group A streptococcus testing), and treatment (eg wound dressing)1. They require specific skills that are based on both knowledge and manual abilities2-4. Along with communication, knowledge, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and reflection, technical skills are a dimension of medical competence5 and a part of the general practice curriculum in many countries6,7. Lists of core technical procedures have been developed in Canada, the US and Australia to serve as bases for training general practice students, but none are currently available in France2-4.

Several studies have attempted to describe the technical procedures performed in general practice, especially in the above-cited countries8-21, and it is of note that many found that rural GPs perform more technical procedures than urban GPs10-15,18. However, most studies had limitations in the data collection process (declarative data)10-12,19-21, the scope of the procedures addressed (in the absence of standard classification)13,14,16-18, or the healthcare actors involved (including students or specialists other than GPs)9,15. In particular, they were performed in at least 18.4% of encounters in Australian general practice in 2015–168. However, no comparable French data have been published.

The aim of the present study was therefore to describe the frequency and type of technical procedures performed in French general practice, and to assess the procedure determinants, in particular rurality.

Methods

Study design

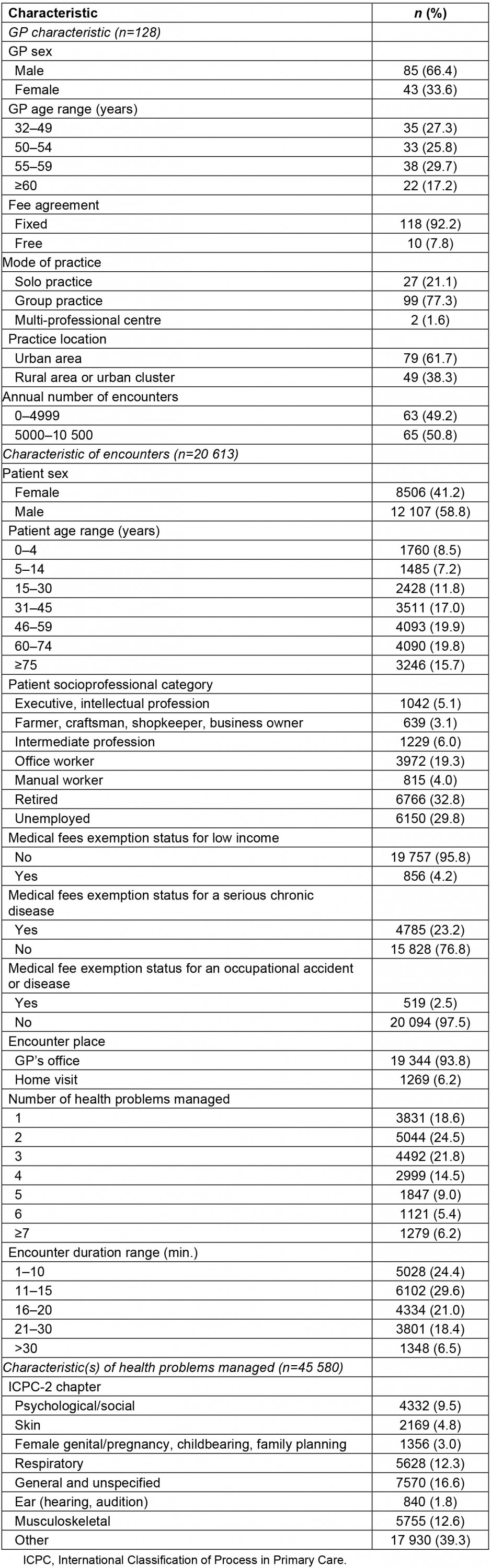

This study was ancillary to the ECOGEN (Eléments de la COnsultation en médecine GENérale) study, an observational, cross-sectional, multicentre, nationwide study conducted in French general practice from November 2011 to April 201222. Its aim was to describe the clinical activity of French GPs. It involved a representative sample of 128 centres (offices of GPs who were also interns’ trainers) attached to one of the 27 collaborating French medical universities. All encounters at the office and home visits were included during 20 working days distributed across the study period. Patient refusal to participate was the only non-inclusion criterion.

Data collection

Data were collected by 54 interns in general practice, acting as observers of their GP trainers. They had been trained to collect and code encounter data according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2)1. They collected the data of each encounter and entered these daily into a secured central database using a dedicated server.

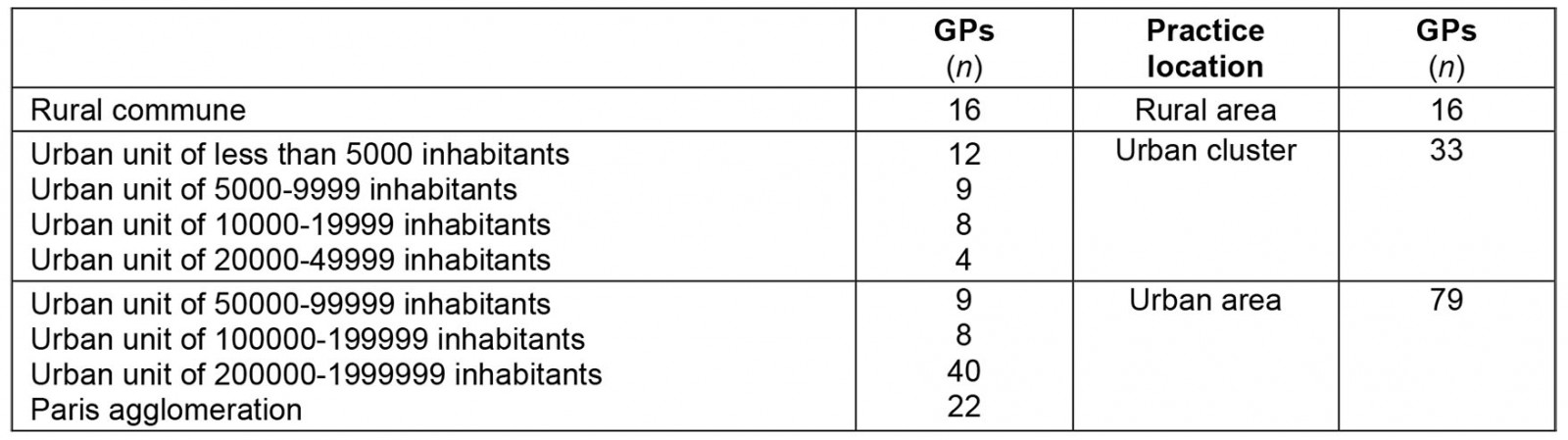

Data about GP characteristics included age, sex, fee agreement (fixed or free), mode of practice (solo practice, group practice, practice in a multi-professional centre), annual number of encounters, and practice location. Three categories for GP practice location (rural area, urban cluster, urban area) were derived from the classification of the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques, INSEE), based on 2007 census data and using both the name of the commune and the postcode23. These categories were defined according to the number of inhabitants in each territory unit (Appendix I).

Data concerning the patient and the encounter included age, sex, socioprofessional category, medical fee exemption status (for low income, for serious chronic disease, for accident or occupational disease), place of encounter (at the office or home visit), number of health problems managed, and duration of encounter. The health problems managed and the associated processes of care performed or planned were coded according to the ICPC-2 classification1. For each process of care coded, the intern had to describe it further by recording a specific verbatim.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

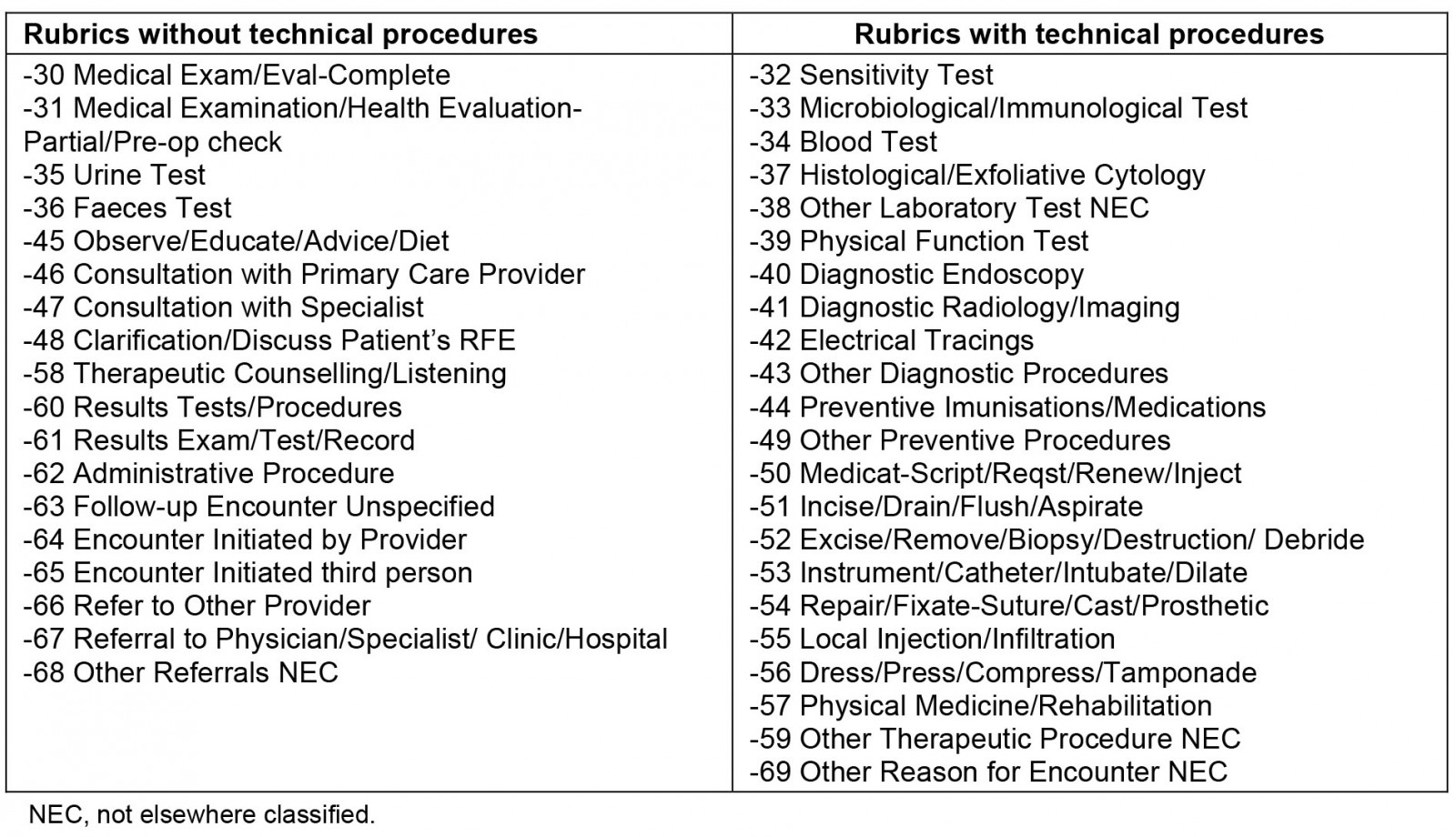

Among processes of care performed, those coded with the ICPC-2 rubrics corresponding to clinical, administrative, or coordinating processes of care were excluded (Appendix II), and among those remaining all non-technical procedures based on the recorded verbatim were also excluded. A technical procedure was considered as a process of care that required both knowledge and manual abilities, excluding the routine clinical examination procedures and purely interpretative tasks (eg interpretation of radiography)2-4. Routine clinical examination procedures were defined, according to WONCA classifications, as inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation; visual acuity and fundoscopy; otoscopy; vibration sense; vestibular function; digital rectal and vaginal examination; vaginal speculum examination; blood pressure recording; indirect laryngoscopy; and height/weight measurement1.

Data management and analysis

The GP practice location variable was categorised as either urban (territory units of 50 000 inhabitants or more) or rural area/urban cluster (territory units of less than 50 000 inhabitants). Health problems managed were regrouped, merging the 17 ICPC-2 chapters into eight categories in order to distinguish psychosocial problems from the main somatic problems concerned by technical procedures. The various technical procedures were classified according to the framework of the International Classification of Process in Primary Care (IC-Process-PC)24.

The frequency of technical procedures was compared according to GP practice location using the χ2 test. We analysed the determinants of performing technical procedures on the level of the health problems managed, which we considered the most specific level because a technical procedure is usually performed to prevent, diagnose, or treat a particular health problem. The dependent variable analysed was therefore the performance of at least one technical procedure per each health problem managed (yes/no). To study the influence of each variable of interest on the dependent variable, we performed bivariate then multivariate analyses, using logistic regression models. These analyses were based on a hierarchical mixed-effect model with random intercepts on physician and encounter effects, including three levels: the physician, the encounter, and the health problem managed. To compare the multivariate model to the ‘null model’ (with no fixed effect predictor), we calculated the random effect variances and the intraclass correlations for both physicians and encounters, as well as the Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion fit statistics. We also used the marginal R² and the conditional R² to express the variance explained by the multivariate model. Statistical significance threshold was set to 5%, and Stata v16 (StataCorp; http://www.stata.com) was used to perform analyses.

Ethics approval

The ECOGEN study was approved by the National Data Protection Commission (Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés, no. 1549782) and the regional ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est IV, No. L11-149).

Results

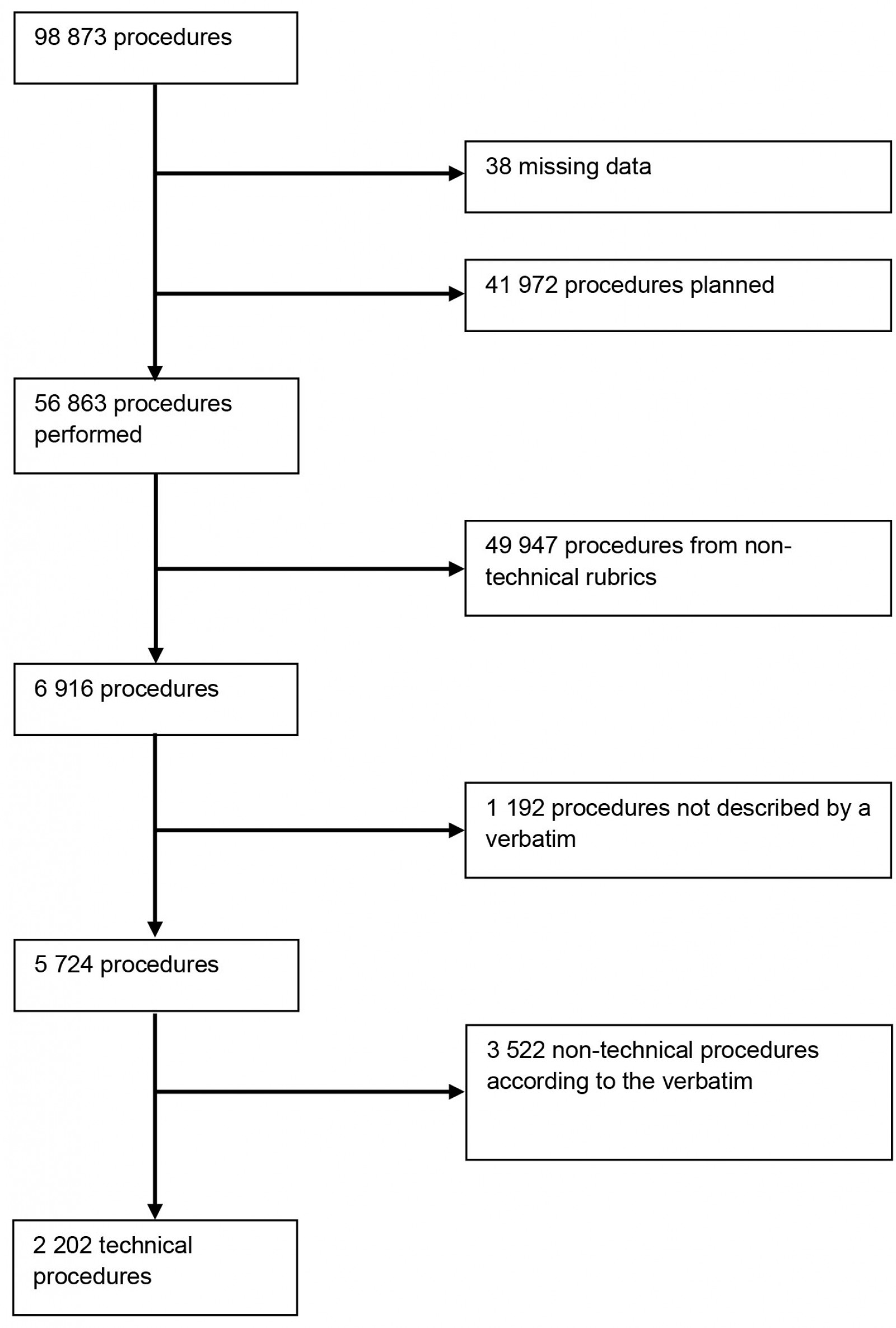

The study investigators directly observed 20 613 patient–GP encounters, including 45 580 health problems managed and 98 873 associated processes of care (including 41 972 planned and 56 863 performed). There were 2202 technical procedures performed during the study period and included herein (Fig1). At least one technical procedure was performed in 2046/20 613 encounters (9.9%) and for 2114/45 580 health problems managed (4.6%). The characteristics of GPs, encounters and health problems managed are reported in Table 1. In particular, 38.3% of GPs practised in a rural area or an urban cluster and 61.7% in an urban area.

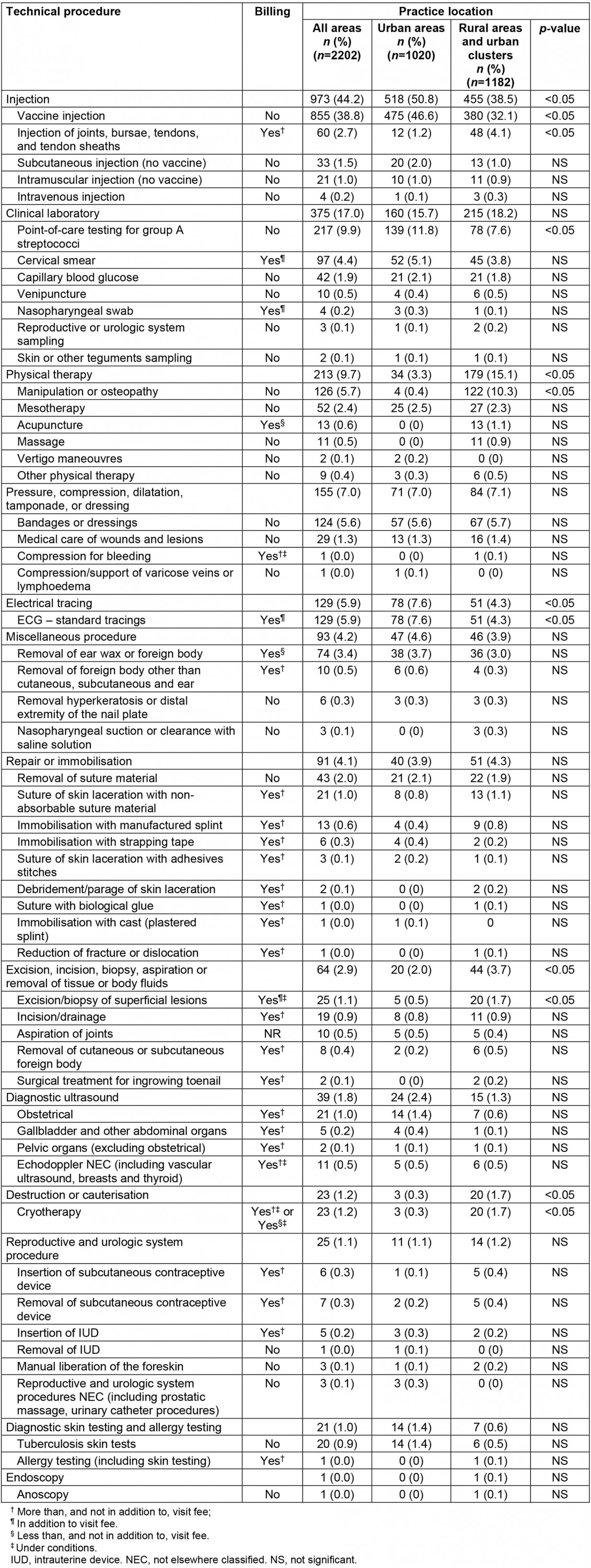

The two most frequent groups of technical procedures performed were injections (44.2% of all technical procedures), and clinical laboratory procedures (17.0%). Physical therapies (15.1% v 3.3%), excision/incision/biopsy/aspiration or removal of tissue or body fluids (3.7% v 2.0%), and destruction or cauterization (1.7% v 0.3%) were more often performed by GPs practising in rural areas or urban clusters than in urban areas. Conversely, injections (50.8% v 38.5%) and electrical tracing (7.6% v 4.3%) were more often performed by GPs practising in urban areas (Table 2).

The two most frequent technical procedures were vaccine injections (38.8% of all technical procedures) and point-of-care testing for group A streptococci (9.9%). The following procedures were more often performed by GPs practising in rural areas or urban clusters: injection of joints, bursae, tendons and tendon sheaths (4.1% v 1.2%), manipulation and osteopathy (10.3% v 0.4%), excision/biopsy of superficial lesions (1.7% v 0.5%), and cryotherapy (1.7% v 0.3%). All of these procedures are billed to the patient (€26.13–68.80 (~A$42.90–112.96), instead of the visit fee), apart from manipulation and osteopathy. Conversely, the following procedures were more often performed by GPs practising in urban areas: vaccine injection (46.6% v 32.1%), point-of-care testing for group A streptococci (11.8% v 7.6%), and ECG (7.6% v 4.3%). Among these, only ECGs are billed (€14.26 (~A$23.42), in addition to the visit fee; Table 2).

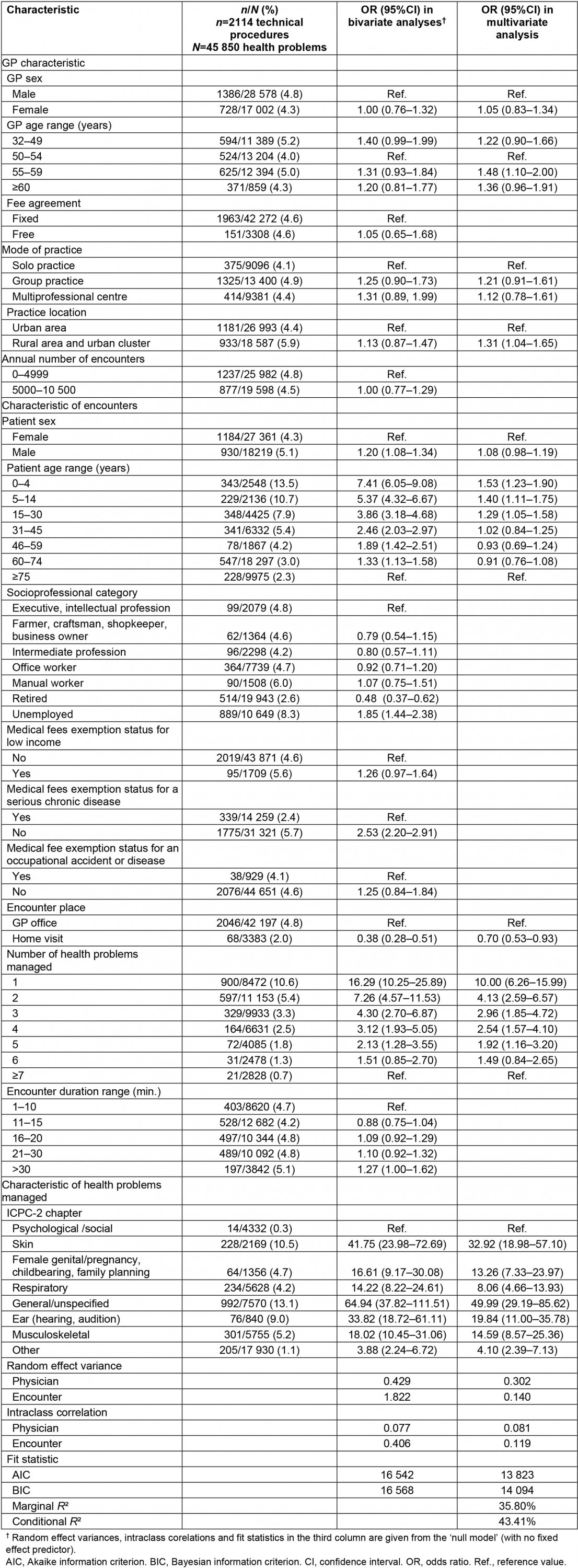

According to bivariate analyses, performing technical procedures was not associated with GPs’ sex, age, fee agreement, mode of practice, practice location or annual number of encounters. Encounters with patients who were male (odds ratio (OR)=1.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08–1.34), younger (ORs increasing from 1.33 (95%CI 1.13–1.58) in those aged 60–74 years to 7.41 (95%CI 6.05–9.08) in those aged 0–4 years, and with respect to patients aged 75 years or more), unemployed (OR=1.85, 95%CI 1.44–2.38), with respect to executives, or without fee exemption status for a serious chronic disease (OR=2.53, 95%CI 2.20–2.91) more often included a technical procedure. Conversely, retired patients had technical procedures less often than executives (OR=0.48, 95%CI 0.37–0.62). Technical procedures were more often performed when fewer health problems were managed during encounters (ORs from 2.13 (95%CI 1.28–3.55) for five health problems to 16.29 (95%CI 10.25–25.89) for one health problem; with respect to seven or more health problems), and less often performed if encounters took place at patients’ homes rather than at GPs’ offices (OR=0.38, 95%CI 0.28–0.51). A technical procedure was more often performed to manage a health problem classified as general/unspecified (OR=64.94, 95%CI 37.82–111.51) or concerning the skin (OR=41.75, 95%CI 23.9–72.69), the ear (OR=33.82, 95%CI 18.72–61.11), the musculoskeletal system (OR=18.02, 95%CI 10.45–31.06), female health/family planning (OR=16.61, 95%CI 9.17–30.08), the respiratory system (OR=14.22, 95%CI 8.22–24.61), or another ICPC-2 body chapter (OR=3.88, 95%CI 2.24–6.72) other than psychological or social chapters (Table 3).

In the multivariate analysis, GPs practising in a rural area or an urban cluster performed technical procedures more often than those practising in an urban area (OR=1.31, 95%CI 1.04–1.65). No association was found with patient sex or with medical exemption status for a serious chronic disease (Table 3).

Figure 1: Flowchart of technical procedure selection.

Figure 1: Flowchart of technical procedure selection.

Table 1: Characteristics of GPs, patients, encounters, and health problems managed

Table 2: Distribution of technical procedures according to GP practice location

Table 3: Characteristics of GPs, encounters and health problems associated with technical procedures per health problem managed in bivariate and multivariate analyses

Discussion

This study provides insight on the performance of technical procedures by French GPs and the influence of rurality. It showed that at least one technical procedure was performed in 9.9% of encounters and for 4.6% of health problems managed. Injections were the most frequent group of procedures performed, followed by clinical laboratory tests, and vaccine injection was the most frequent procedure, far ahead of point-of-care testing for group A streptococci. GPs practising in rural areas or in urban clusters performed more technical procedures than those practising in urban areas. Some complex technical procedures more frequently performed by GPs practising in rural areas and in urban clusters are not billed above the visit fee.

Comparison with existing literature

Among the published studies8-21, only the one conducted by Britt et al in Australia was based on frequency estimators and a procedure classification similar to that used herein8; therefore comparisons were only made with this report. The overall frequency of technical procedures in France was around half of that reported in Australia (18.4%, including vaccine injections). We found that injections were the most frequent group of procedures performed in France, as also observed in Australia (30.1%); however, the proportion of vaccine injections among these was greater in France as compared to Australia (18.3%). The high frequency of vaccine injections in the present study is consistent with the strong association between technical procedures performed and health issues classified in the ICPC-2 ‘general/unspecified’ chapter, which includes the ‘preventive medicine’ rubric. The second most frequent group of procedures corresponded to clinical laboratory procedures, mainly point-of-care testing for group A streptococci. The frequency of all clinical laboratory procedures was not reported in the Australian study, and point-of-care testing for group A streptococci is not routinely done in Australia25. It is of note that in the Australian study procedures were grouped into ‘excision, removal tissue, biopsy, destruction, debridement, cauterization’ and ‘incision, drainage, flushing, aspiration, removal body fluid’, whereas in the present study approximately the same procedures were included but not in the same groups (‘excision, incision, biopsy, aspiration or removal of tissue or body fluids’ and ‘destruction or cauterization’); combining these arrives at a similar content, and this was more frequent in Australia (18.9%) than in France (3.9% of all technical procedures; data not shown). Taken together, technical procedures are less frequent in France than in Australia and a lower proportion of these are complex.

According to the present study, French GPs practising in rural areas or in urban clusters performed more technical procedures than those practising in urban areas; this may explain at least in part the higher frequency of technical procedures performed in Australia that did not formally investigate this aspect8. Several studies conducted in Australia, the USA, Israel, and various European countries have also found that rural GPs performed more technical procedures than urban GPs10-15,18. In particular, complex procedures such as infiltrations of joints11 and minor surgery13-15 were more often performed by rural GPs, which is consistent with the findings presented herein, considering that the group ‘excision, incision, biopsy, aspiration or removal of tissue or body fluids’ roughly corresponded to minor surgery procedures. This, as well as the more frequent performance of complex technical procedures in general by rural GPs, may be due to the rarity of specialists (such as surgeons or dermatologists) in such areas26. To our knowledge, the more frequent performance of cryotherapy and manipulation/osteopathy by French GPs in rural areas or urban clusters had not been identified previously.

Three procedures were more often performed by French GPs practising in urban areas: vaccine injections, point-of-care testing for group A streptococci, and ECGs. These findings are consistent with previous data from Ontario and Iowa regarding vaccine injections, ECG, and laboratory procedures as a whole15,17. Lack of GPs in French rural areas may have increased the proportion of vaccine injections and point-of-care testing performed by other healthcare professionals such as nurses or pharmacists27. In addition, the higher workload of rural GPs28 may push them to delay time-consuming and non-urgent procedures required for routine monitoring, such as ECGs.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first published study providing data on the performance of technical procedures by French GPs. It was a large multicentre national study, based on a detailed and comprehensive practice-based collection of health problems managed along with the associated processes of care, including the technical procedures. In addition, both health problems and technical procedures were classified consistently.

GPs involved in the ECOGEN study were all trainers, which may entail differences with other GPs. However, they proved to be representative of French GPs for age, sex, and practice location22. In addition, according to another study conducted in France, patients of GP trainers can be considered to be similar to those of non-trainer GPs; however, among technical procedures, GP trainers performed slightly more seasonal flu vaccination than non-trainers, although it is not known whether this applies to other vaccinations29.

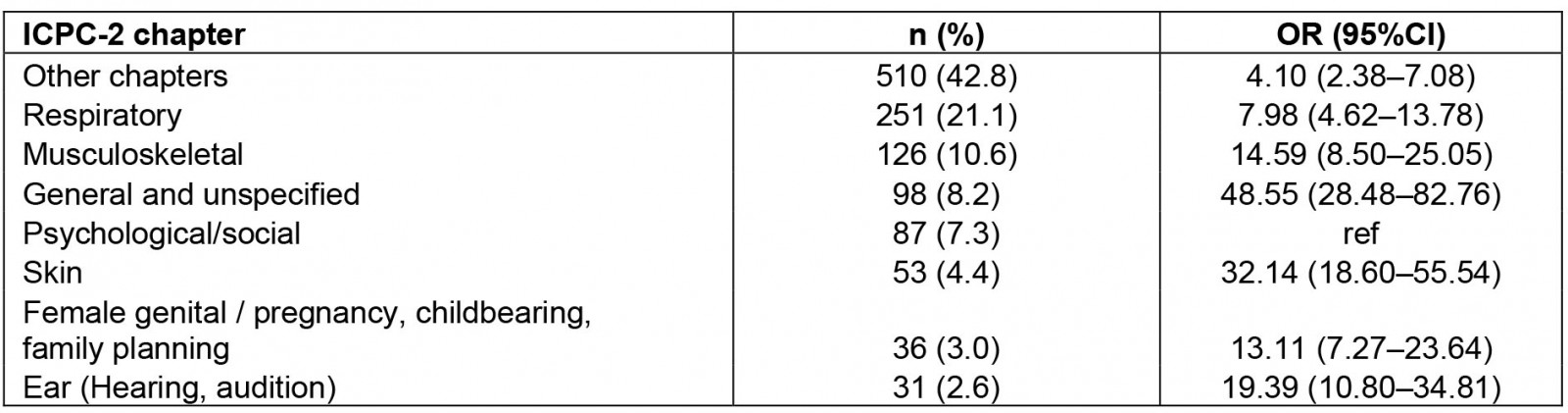

We excluded 1192 procedures not described by a verbatim (17.2% of those eligible), which could lead to an underestimate of the number of technical procedures performed. However, most of these excluded procedures were associated with health problems classified in ICPC-2 chapters not likely compatible with performing technical procedures, such as the ‘other’ chapters and the respiratory chapter (Appendix III).

It is of note that only 12.5% of the GPs participating in the ECOGEN study practised in a rural area, which precluded the study of this group specifically. We therefore merged the groups of GPs practising in rural areas and in urban clusters in order to increase the statistical power for comparing rural and urban practices, and comparison with other studies in this regard has to be interpreted with caution.

Since the time when the ECOGEN was conducted, some task shifting from GPs to other primary care professionals has emerged in France. The concerned tasks include some technical procedures such as vaccine administration, which is now partially allowed to nurses, pharmacists and midwives and may be less often performed by GPs30.

Implications

The frequency of technical procedures undertaken by GPs in France seems low, and it is of note that most are simple procedures. This suggests that there may be certain barriers to performing technical procedures, and that this may be different in more rural than urban areas; this has previously been reported, and barriers include lack of time, fear of complications, lack of experience and training, as well as inadequate fees for the time, skills, legal protection, and equipment needed20,31. Further studies are therefore required to describe needs of patients and the potential barriers to performing technical procedures, with a special emphasis on the location of patient care.

Conclusion

A technical procedure was performed in approximately 1 in 10 encounters in France, which is approximately half the rate reported in Australia. These procedures were more frequently performed and more complex when they were performed in rural areas and urban clusters. More studies are required to assess patient needs and potential barriers regarding technical procedures. Such assessment should help to design training of primary care professionals on technical procedures according to countries and eventually to rural and urban areas of practice.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the ECOGEN study group, including the steering committee, the 54 residents and the 128 GP trainers. The members of the steering committee were Laurent Letrilliart, Alain Mercier, Irène Supper, Matthieu Schuers, David Darmon, Pascal Boulet, Dominique Ambros, Madeleine Favre, Gil Mury, Bernard Gay, Denis Pouchain, Eric Van Ganse, Philippe Ameline, Anne-Marie Schott, Angelique Denis. The interns (trainees) were: Céline Alexanian, Clement Barletta, Solene Baron de Preville, Muriel Baudoin-Bion, Naïma Belarbia, Clarisse Bertrand, Anne-Sophie Billet, Emilie Boulard, Emilie Breillat, Claire Brunet, Claire Camilleri, Hélène Carrier, Mathieu Carron, Nelly Cordeiro, Clément Coutarel, Sophie Dargent, Sarah Darriau, Hubert de Lary, Karen Denis, Yohana Dery, Isabelle Duquenne, Guillaume Farcis-Morgat, Charlotte Favier, Sarah Filoche, Mohamad Hamade, Marion Helly, Laura Hsiung, Thibault Lelong, Nathalie Levernier, Julia Marquant, Prisca Martin, Caroline Martin-Bouyer, Ryma Metahri, Lesley-Ann Montigneaut, Noémie Morel, David Nakache, Claire Parker, Eric Pernollet, Solène Petitclerc, Alicia Pillot, Henri Plancke, Fanny Poirot, Thomas Proboeuf, Sophie Quien, Marie-Camille Rault-Tandonnet, Charlotte Regnier, Yohan Saynac, Saphanie Son, Damien Steciuk, Aurélie Urena-Dores, Yannick Vacher, Maxime Veques, Lucile Wies, Elodie Youssef. The GP trainers were Ahmed Aadjour, Isabelle Aubin-Auger, Ghislaine Audran, Nadine Ayme, Catherine Bageot, Jérôme Bard, Bruno Beauchamps, Olivier Bisch, Paul Blanchet, Jean-Michel Blondel, Pierre Bobey, Jean-Yves Borgne, Jean-Yves Breton, Agnès Bryn, Martin Buisson, Marie Cabanas, Gérald Catsanedo, Maxime Cauchie, Nicole Caunes, Cerisier-Cornillot, Patrick Charbit, Pascal Clerc, Laurent Convert, Françoise Corlieu, Thierry Cornille, Alain Couatarmanac’h, Claude Danner, Jean-Claude Darrieux, Alain Dasse, François de Golmard, Gilles de Lorenzi, Anto de Pavljasevic, Pierre-François Delzanno, Nicole Derain, Pierre Deveche, Vincent Diquero, Bénédicte Chevreau, Elise Dubreuil, Pierre Dupont, Charline Dupont, Richard Dymny, Catherine Elsass, Pierre Eterstein, Gilles Faivre, Eric Fanjeaux, Emmanuelle Farcy, Claudine Fity, Vasantha Flory, Anne Girard, Christophe Girault, Sabine Grutter, Murielle Guillier, Thérèse Guyenne-Chambru, Christophe Haguet, Jean-Yves Hascoet, Sophie Haudidier, Sylvain Hirsch, Gaëtan Houdard, Hélène Hubail, André Kastelik, Sylvain Kichelewski, Xavier Lainé, Valérie Lapouge, Christian Larcheron, David Laurent, Laurent Laval, Serge Lavaure, Mireille Lavigne, Yves Leborgne, Odile Lion, Viviane Mannevy, Jean-Michel Mathieu, Laure-Emmanuelle Mavraganis, Denis Perrot, Yvon Petrault, Christophe Pigache, Maurice Ponchant, Véronique Poupet, Daniel Reynolds, Emmanuel Robin, Marie-Hélène Robineau, Jean-Loup Roblot, Larisa Savan, Pierre Sebbag, Patrick Serey, Michel Serraille, Corinne Simoneau, François Tahon, Jean Louis Teruel, Audrey Tordoir, Christian Verot, Valérie Zéline.

We thank Philip Robinson (DRS, Hospices Civils de Lyon) for help in manuscript preparation.

The ECOGEN study was supported by the French National College of Teachers in General Practice via a grant from Pfizer.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

appendix II:

Appendix II: Selection of ICPC-2 processes of care including technical procedures or not

appendix III:

Appendix III: Distribution of the 1192 procedures excluded because they were not described by a verbatim, by health problem ICPC-2 chapter, with their OR from multivariate analysis

You might also be interested in:

2022 - Managing hospitalized patients with bacterial infections: the price-to-pay upon site of infection

2020 - Does driving using a Green Beacon reduce emergency response times in a rural setting?