Introduction

WHO defines mental health as ‘a state of health in which every individual realises his or her potential, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community’1. Several components contribute to mental health, including social, psychological and biological factors1, all of which can be influenced by one’s geographical living location. The heightened burden of poor mental health in rural locations is evident. Despite the prevalence of diagnoses for mental disorders being similar in urban and rural locations, suicide rates are 40% higher in rural communities2.

The term ‘community’ is often inappropriately used throughout political processes3. The concept suggests engaging with the community to develop ‘community based’ programs, a ‘quick fix’ for many economic and social concerns3. There have been recognised benefits to genunine engagement of commuity members3. When mental health is the focus, community engagement allows people residing in rural communities to contribute to their community, positively impacting on mental health1.

Community engagement is commitment from the community that includes the individuals, their support structures and social networks, organisations providing relevant services to individuals, and relevant community stakeholder relationships4. The resultant community development strengthens social networks and capital learning to an enhanced awareness of social concerns, and the community taking responsibility for interventions4.This develops community empowerment where people residing in rural locations can independently and collectively influence one another4 and contribute to their community. Along with contributing to their community, another determinant of mental health is the ability to work productively and fruitfully1.

People living in rural locations often report a high subjective wellbeing (SWB) if their productivity is maintained – despite experiencing poor mental health, chronic conditions or persistent pain5. High SWB may be due to the rural ideal of stoicism: ‘the endurance of pain or hardship, without the display of feelings and without complaint’6. However, stoicism may not be the only factor contributing to the stigma of mental health in rural communities. Other factors may be privacy, distance to the nearest healthcare service, or associating SWB with productivity alone, rather than with quality of life5. The rural view of SWB could be why people living in rural communities score higher in happiness surveys, despite having poorer mental health outcomes7. SWB may also impact upon a rural community’s level of readiness to address the mental health of those residing in rural communities.

Communities vary in their level of engagement and readiness to adapt or even acknowledge social concerns8. This can significantly influence the success of interventions supported by a local community8. Models like the Community Readiness Model (CRM) are strategically designed to determine a community’s current level of readiness to action social concerns9. When interventions like the CRM involve local community members, they are more likely to be culturally appropriate for communities8. This encourages community ownership and longevity of interventions8, further fostering community engagement, participation and empowerment.

To engage the community in some cases, culture and gender should be considered in frameworks. Despite many frameworks claiming to be community based, often cultural norms are not acknowledged. For example, gender-matching participants with researchers can be essential in some cultures due to differences in men and women’s business10. Gender matching in research supports true community engagement, in participatory frameworks.

Previous studies11-16 have considered participatory frameworks for mental health in rural communities. However, there have been no reviews to date that have focused on the process of community engagement for mental health in rural communities. Nor is there a recommended established framework of community engagement. This review aims to examine how community engagement, participation and empowerment were used in the development and implementation of interventions aimed at improving mental health of adults residing in rural communities.

Methods

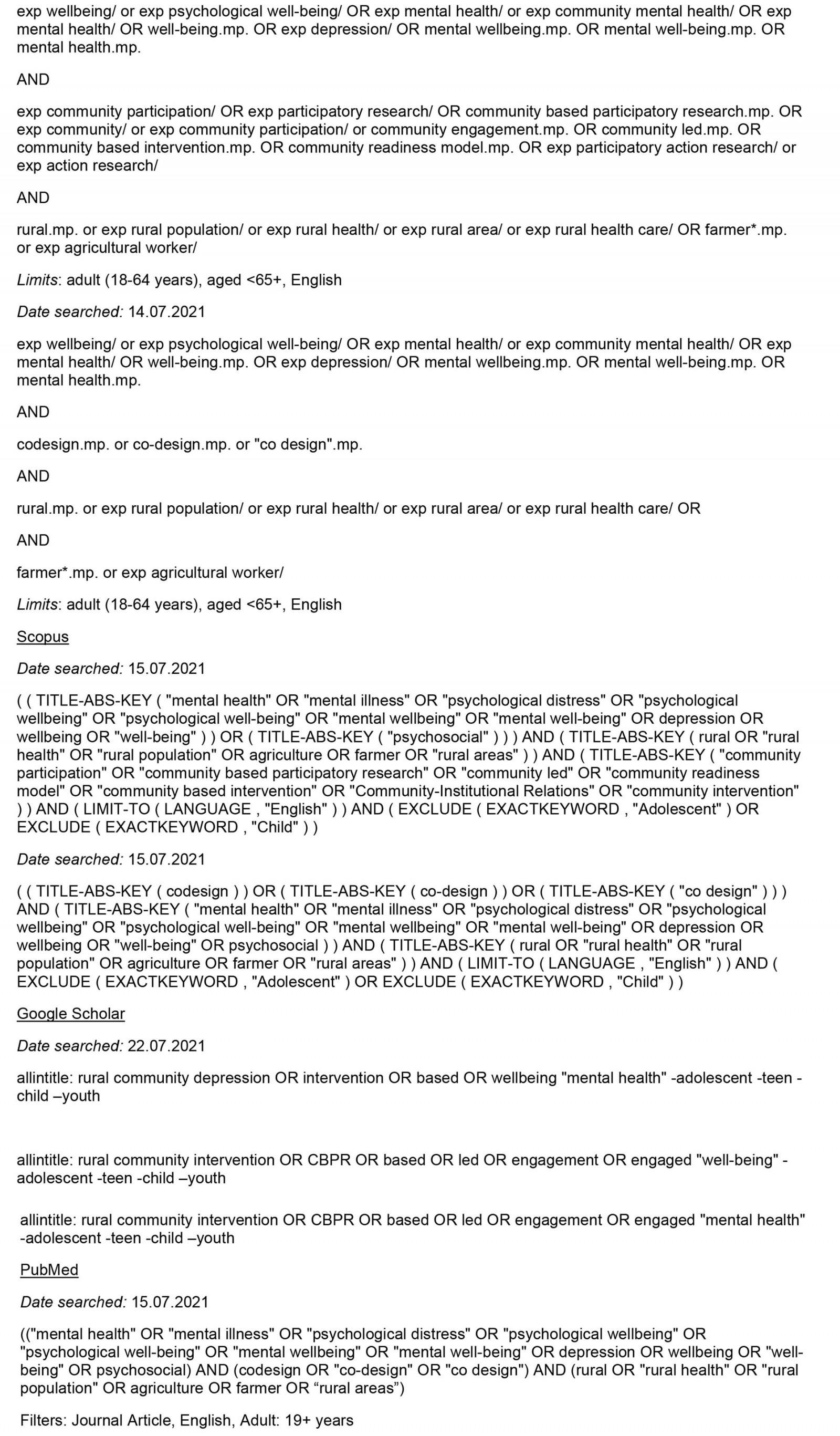

A systematic search was conducted in July 2021 to identify research investigating the development and implementation of community engagement interventions aimed at improving the mental health of adults residing in rural communities. The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines17 (Fig1).

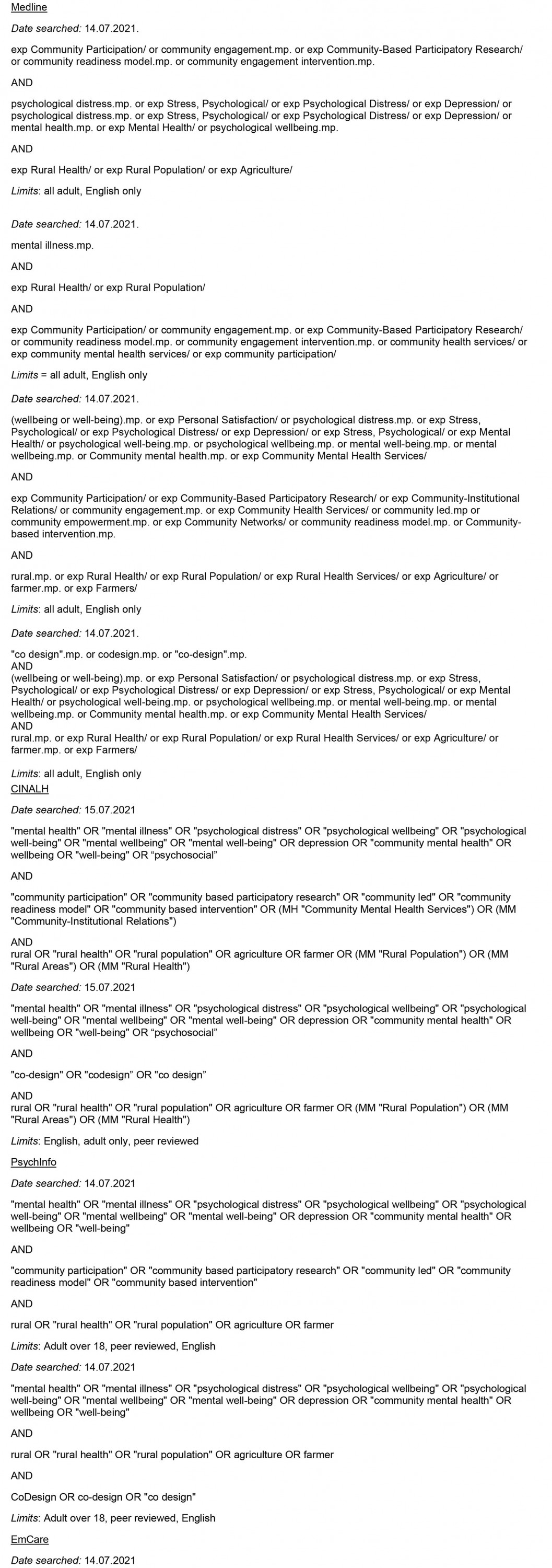

An amalgamation of keyword search and MeSH terms, with Boolean structure, was utilised for the following databases: Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo, EmCare, Scopus, PubMed and Google Scholar. Keyword search and MeSH terms were amended based on the database, with the following themes: ‘community engaged’, ‘intervention’, ‘mental health’ and ‘rural’. For a full list of search terms, see Appendix I.

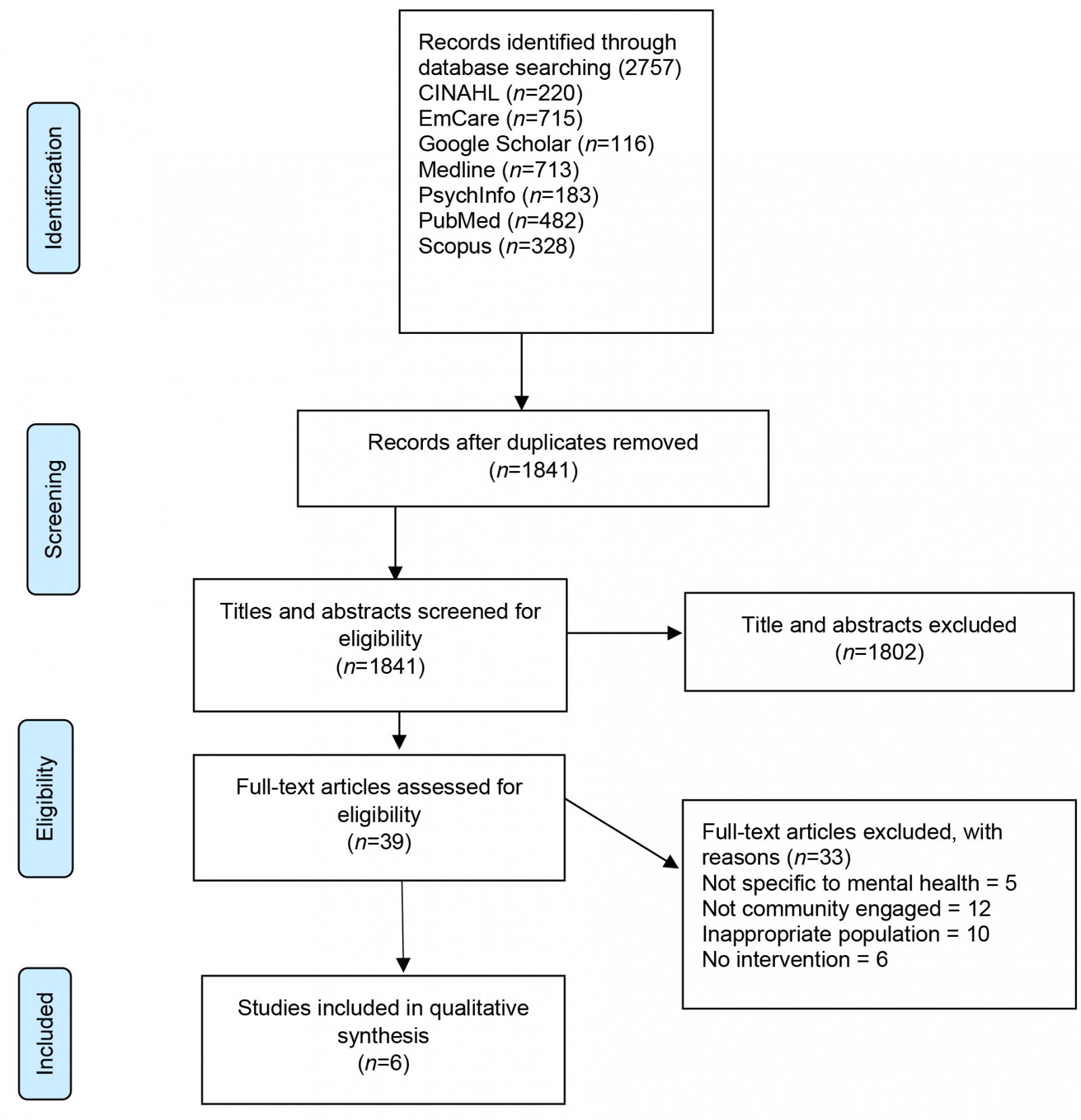

The aim of this review was based on the PICo (Population, Interest, Context) framework18 (Table 1). The population was adults within a rural cohort. ‘Rural’ is defined as any location that is not urban, with urban recognised as a concentrated spatial distribution of people whose lives are not focused on agriculture activities19. Studies included the used of community engagement. Community engagement requires the involvement of individuals, their support structures and social networks, organisations providing relevant services to individuals and relevant community stakeholder relationships4. Community engagement was to be used in the development or implementation of the intervention. The context was mental health. Studies selected for inclusion were original, peer-reviewed studies published in English. Studies from database inception to the search date (28 July 2021) were included.

Studies focusing on children and adolescents were excluded. Identified studies focusing on comorbidities associated with mental health or a clinical diagnosis of mental illness based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)/International Classification of Diseases (ICD) conditions were also excluded, ensuring the present research was focused on community mental health, not personal illness. Studies were excluded if the community engagement did not occur in the development or implementation of an intervention.

The development of the search was undertaken by one author (KR) with the guidance of an independent research librarian. Duplicates were removed by first reviewer (KR). The PRISMA flow diagram was used to guide screening of the remaining articles by the first reviewer (KR) and second reviewer (SV). EndNote libraries were shared to achieve this. To maintain rigour, the six included full-text articles were evaluated for eligibility by a third reviewer (FB).

Critical appraisal of studies inluded in the present systematic review was undertaken using the McMaster Critical Review for Qualitative Studies20. To understand the development and implementation of community-engaged interventions to improve the mental health of adults in rural communities, a narrative synthesis was based on information provided in the studies. Data extracted from each study included the methodological quality of the study and study model, the community (location of community, population involved, phase and type of community-engagement methods), the action (purpose of the study, study/intervention duration, data collection methods, data obtained) and the intervention outcomes. The phases of community engagement included pre-development (the phase between origination and initiation of the intervention), developing the intervention and actioning the intervention.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart of the literature search process.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart of the literature search process.

Table 1: Population, Interest, Context framework for the study

Results

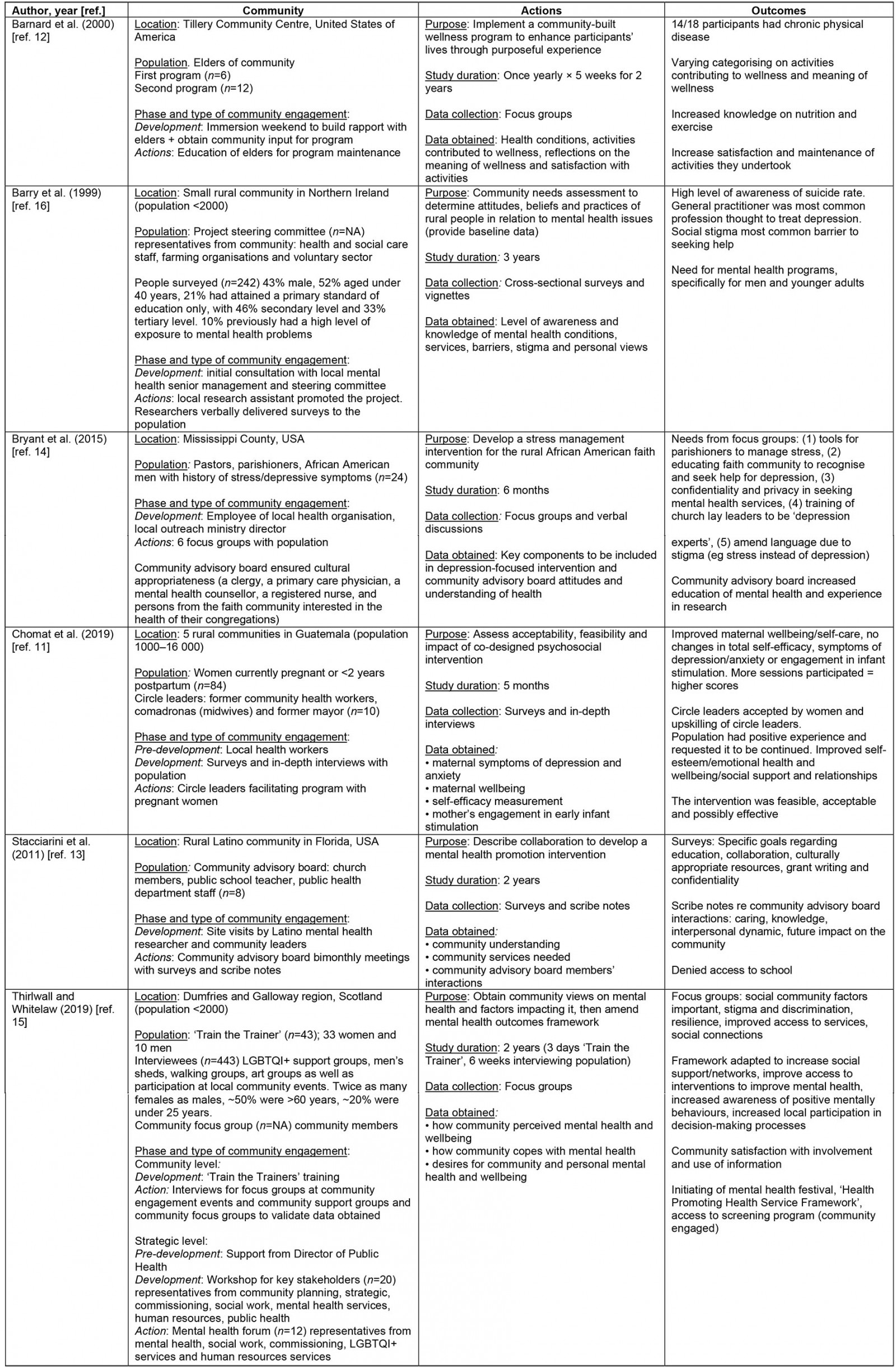

A total of six studies met the inclusion criteria, guided by PRISMA format (Fig1). The data extracted is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Details of included studies11-16

Location

All studies were conducted in rural communities. Three were conducted in the USA, two in the UK and one in Guatemala. Populations ranged from 1000 to 4000 community members.

Population

The sample size of participants had a range of 6–443 participants. Four studies included both men and women. One study included only men and one study included only women. Barnard et al12 focused on the elders of the community12. Six elders participated in the first wellness program. One year later, 12 elders took part in the second wellness program. Barry et al16 had a higher number of participants (242 people surveyed) and initially used a project steering committee (number involved unknown) including health and social care staff, farming organisations and the voluntary sector16. Ten percent of participants had previous high-level exposure to mental health problems. Thirlwall and Whitelaw had a larger number of participants: 43 involved in ‘Train the Trainer’ (33 women and 10 men), which engaged 443 interviewees15. This included twice as many females compared to males, 50% aged over 60 years and 20% under 25 years. A community focus group (number of participants unknown) was used to validate the data, through surveys in the structure of an interview.

Chomat et al also used local healthcare professionals to engage the sample population, which was 84 women pregnant at the time or less than 2 years postpartum and 16 circle leaders (nine former community health workers, six midwives and one former mayor)11. This was similar to the study of Bryant et al, where the local outreach minister identified 24 men to be involved14. The men included pastors, parishioners and African-American men with stress/depressive symptoms. In the study by Stacciarini et al, eight community advisory board members were the source of data13. The board included church members, public school teacher and public health department staff. Recruitment for community engagement varied throughout the studies according to community need determined from consultations. Community engagement methods utilised depended on each community to maximise sample size.

Phases and type of community engagement

Methods of community engagement varied throughout the intervention phases (pre-development, development and action) in each of the studies. Barnard et al used prior relationships between the community and university to facilitate an immersion weekend for occupational therapy students in the development stage12. This allowed the students to build rapport and obtain the elders’ input for program development. When the program was in the action phase, the elders of the community were responsible for taking notes in each session to replicate the program independently.

In the development phase, Barry et al chose to liaise with the local mental health senior management16. Management assisted in developing a community-based initiative including voluntary and legislative sector organisations. When moving into the action phase, a local research assistant promoted the project, and the researchers verbally delivered the surveys to the community. Chomat et al used local health workers who requested the intervention after being involved in another project with the research team11. When developing the project, surveys and in-depth interviews were used with the population, along with circle leaders facilitating the program.

Bryant et al also used an employee of the local health organisation who had an interest in depression and linked the research team in with the director of an outreach ministry14. Both the health employee and ministry director assisted to develop the project and engaged a community advisory board. The board took part in six focus groups to ensure the project was culturally appropriate. Stacciarini et al also relied on community advisory boards for cultural guidance13. The research was originally developed by a Latino mental health researcher, who met with community leaders. This prompted bimonthly meetings between the board and research team. Surveys were used to determine community needs. Scribe notes were also used based on the stage of research.

Thirlwall and Whitelaw made initial contact with community leaders in the pre-development phase15. A ‘Train the Trainer’ technique was used to develop community engagement, and focus groups were held at community engagement events and community support groups (LGBTQI+ support groups, men’s sheds, walking and art groups). Community focus groups were also used to validate the data collected. At a strategic level, researchers held workshops for key stakeholders. The workshops discussed outcomes from the focus groups and mapped out current projects. To action an intervention, a mental health forum identified key outcomes from the workshop. The community engagement methods varied for each study. However, the underlying general purpose remained consistent: that of improving community mental health.

Study duration, data collection and data obtained

Intervention durations ranged from 5 months to 3 years. Of the studies that implemented interventions, qualitative and quantitative outcome measures were used to evaluate the impact of the intervention on community mental health. To determine the results of the 5-month intervention, surveys and in-depth interviews were used11. The surveys included determinants of mental wellbeing (maternal symptoms of depression and anxiety, maternal wellbeing, self-efficacy and mothers’ engagement in early infant stimulation). After the 5-week wellness program in the second year, Barnard et al chose to use focus groups with interview questions12. This clarified participants’ health conditions and reflections (activities that contributed to wellness, the meaning of wellness and satisfaction of program activities). Thirlwall and Whitelaw used discussion focus groups to determine community perceptions of mental health, how the community copes with mental health, along with the desires for community and personal mental health and wellbeing15. Focus groups were also used for feedback on community satisfaction with the intervention.

Varied data collection methods was used for community engagement to develop interventions. Surveys and vignettes were implemented over 3 years for community needs assessment through determining community level of awareness and knowledge of mental health conditions, services, barriers, stigma and personal views16. Surveys were also used over 2 years to determine community understanding, community services needed and community advisory board members’ interactions12. Bryant et al used focus groups over a period of 6 months to find key components to include in the intervention14. Using surveys, focus groups and vignettes, studies were able to adapt the development and implementation of interventions to achieve results.

Intervention outcomes

Outcomes for each study are displayed in Table 1. Three studies in the development phases identified what is required to improve community mental health13,14,16. This included a need for a mental health program specifically for men and younger adults13; a gap in upskilling, education12,13, confidentiality12,13, culturally appropriate language13 and resources12; and goals for collaboration and grant writing12.

The three studies that implemented a community-engaged intervention reported positive outcomes to improve community mental health11,12,15.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first review to examine how community engagement, participation and empowerment are used in the development and implementation of interventions aimed at improving mental health of adults residing in rural communities. In all studies, community engagement was facilitated to include the individual, their support structures, and social networks4. Community participation developed ownership by building social network for increased awareness and moving focus to the responsibility of citizens4. Two studies13,15 demonstrated community empowerment where locals were able to influence each other independently4 to improve the mental health of adults in rural communities.

Using community engagement to develop the intervention prolonged community engagement and resulted in larger sample sizes11,15,16. This allowed trust to be formed between locals and the research team, resulting in participants more freely sharing information21. Results show trust and community engagement can be achieved through fostering local organisations and community stakeholder relationships16. Characteristics of community members involved influenced the sample population. For example, when local health professionals assist in recruiting participants, purposive sampling is achieved21.

Consistent with purposive sampling, the gender of community researchers influences sample characteristics11,14. For example, a greater number of female community champions led to a greater number of female study participants14. Aligning with cultural norms, some rural Indigenous communities have increased project ownership through yarning (informal discussions) to amplify their voices in research22. Informal meetings with Indigenous rural communities can be effective in establishing collaborations for research23. This ensures communication about research is relatable, for a positive influence on participation rates23.

Where informal yarning was used for initial engagement in community13,14, the community advisory boards also had a personal interest in the project. This was evident in their commitment to the project without financial gain, influencing community readiness to change24. These boards often take on the role of an advisor in community-engaged interventions25. They do this through being upskilled to develop research, collect data and facilitate collaborations between community members and researchers25. The upskilling of interested community members demonstrates community empowerment, where locals respond to mental health promotion effectively13,15.

By employing local research assistants the studies showed support for community engagement11,16 and minimised reliance on the research team26. In community participation, ownership of the project is developed, increasing local awareness and moving the focus to the responsibility of locals4. The local community taking on responsibility addresses possible inequalities between researchers and communities that may contribute to data collection being a false representation of community26. This empowers local organisations to influence one another4 to also address community mental health.

Community empowerment aligns with the research team whose initial contact was not through local health workers; but authority figures in the community. Holt et al confirmed that organisation management support highly impacts community readiness24. If management can envision project achievements over a prolonged period of time (1–8 years), there is increased support27. The increased support minimises negative impacts from short-term decreased outcomes27. The studies13,15 reiterated the need for management support to achieve community empowerment, project longevity and successful outcomes.

The elements of community engagement, participation and empowerment align with strategies demonstrated in the CRM to support project longevity and successful outcomes. The use of the CRM to address a social issue, in this case mental health, involves local community members from various sectors of the community28. Using the CRM prior to intervention delivery can determine the community’s readiness to address a social issue, ensuring strategies are culturally appropriate to facilitate community ownership through community engagement, participation and empowerment.

Future research

As evident by the paucity of studies in this review, frameworks to guide research in addressing mental health in rural communities are limited. Prior to delivering interventions that address mental health concerns in rural communities, future research should consider employing an evidence-based framework to assess a community’s readiness for change. A model such as the CRM, which considers community engagement, participation and empowerment, could be appropriate since it may ensure the right intervention is developed and delivered in the right way, by the right people, for the betterment of the community.

Future research in rural communities should also engage local personnel, including health professionals, gender matched to the target population to ensure cultural norms are recognised. More specifically, future research should describe in greater detail the protocols used for community engagement, intervention delivery and assessment to facilitate translation of interventions to other communities so direct comparisons of effectiveness across geographic boundaries can be conducted. Finally, the included studies that only focused on the development of the intervention should consider continuing community consultation to implement the developed intervention to examine its effectiveness.

Limitations

This review has a number of limitations. To capture as many potential studies as possible, the search strategy was deliberately broad. Despite this, only a small number of studies met the inclusion criteria. This likely reflects the paucity of research specifically examining how community engagement, participation and empowerment are used in the development and implementation of interventions aimed at improving mental health of adults residing in rural communities. Moreover, the included studies are only from three countries. This again reflects the limited research and makes the generalisability of the findings to other regions difficult. The review only included studies focused on adult populations and therefore translation of findings or recommendations to younger populations is not feasible. Only studies published in English were included in the present review and it is therefore possible that there are some relevant studies published in other languages.

Included studies are not without limitation. Data were collected using only surveys and focus groups. An absence of within-study reporting regarding thematic saturation and details of data collection makes study replication difficult and contributes to the heterogeneous nature of included studies. Community consultation and feedback on interventions are limited. Determining the success in developing and implementing interventions appears to be relative to each community and community members involved. This results in a lack of transferability across rural communities.

Conclusion

The studies included in this systematic review identified similarities in developing and implementing community-engaged interventions to address mental health of adults living in rural communities. Community engagement requires the early involvement of local community members. Community engagement should involve a local research assistant with a background in health or local health professional to engage the sample population. Community participation should upskill local health professionals as community researchers. Community empowerment requires support from community management and that the initial contact with community be through local authorities.

Overall research into community-engaged interventions to address the mental health of adults living in rural communities is emerging. Due to the varying culture of each rural community and stigma toward mental health, there are limited frameworks that have been adapted to address mental health. To achieve community engagement, participation and empowerment in rural communities, more research into implementing interventions guided by pre-existing models such as the CRM is needed. This could determine if these models are transferable across rural communities to address social concerns like mental health.

References

You might also be interested in:

2009 - What older people want: evidence from a study of remote Scottish communities