Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced global public health researchers to adapt their approaches according to restrictions to control the pandemic1. Under these circumstances, standard face-to-face interaction in research activities is replaced by alternatives of remote data collection2. Hence, telephone interviews and computer-assisted telephone interviews have become a major alternative to maintain social distancing. Also, messaging app interventions have emerged as a main method of health education and health promotion during lockdown periods2. Despite challenges of data quality, these remote methods of health research are safe and effective during pandemic situations.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, research was conducted mainly using telephone interviewing due to its cost effectiveness and time efficiency3. Hensen and colleagues highlighted that remote data collection mainly relied on mobile phones but would still be challenging in low- and middle-income countries2. The use of remote data collection sounds promising and easy in urban and semi-urban areas but its feasibility and suitability in a rural area are still not clear. With 2.3 million fixed-access telephones and 27.7 million cell phone subscribers in 2020 in Sri Lanka4, this remote approach in data collection seemed to be a fair alternative for a population of 21.8 million and 5.1 million households. While the hotlines, health message delivery services and smartphone-based interventions were implemented during the lockdown period, an assessment of the generalizability of telephone interview and the coverage and feasibility of app-based interventions is not available, especially for rural and remote areas of the country, where the availability of this digital technology may still be an issue. In this regard we share our experience of large-scale telephone interviews from a rural setting in Sri Lanka to understand related issues and for better design of research and interventions in future.

Methods

We present data from a large-scale, population-based pregnancy cohort, Rajarata Pregnancy Cohort (RaPCo)5, which was conducted in the Anuradhapura district in Sri Lanka. Anuradhapura is the geographically largest district in Sri Lanka (7719 km2) with a population density of 129 persons per square kilometer 6. It is situated nearly 200 km away from Colombo, which is the largest commercial and administrative district in the country with a population density of 3417 persons per square kilometer6. RaPCo recruited 3374 first-trimester pregnant women who were registered with public health midwives at the field antenatal clinics in 22 Medical Officer of Health areas of Anuradhapura district. Participants were recruited to the cohort within the third quarter of 2019 and over 95% of eligible pregnant women in the district were enrolled. During recruitment, contact numbers were collected from all pregnant women with permission to contact them to share investigation results, appointments and follow-up data collection. Third-trimester follow-up and hospital-based delivery data collection of RaPCo were impossible during COVID-19 lockdown. To overcome this challenge and especially to provide psychological support to pregnant and postpartum women during the pandemic, we conducted a round of telephone interviews for all RaPCo participants. Five female medical graduates awaiting internship were trained on telephone interview technique, with emphasis on politeness, telephone etiquette, basic counselling skills and essential perinatal health information. Telephone interviews were conducted mainly during the lockdown period and completed within 3 months. If the first attempt failed, several attempts to contact pregnant women were done on same day and then in subsequent days for the next 2 weeks. A second round of calls was done to contact those who were unavailable or busy the first time. In addition to telephone interviews, we specifically enquired about the use of messaging apps to deliver health education/promotion contents during the lockdown period.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka (ERC/2019/07).

Results

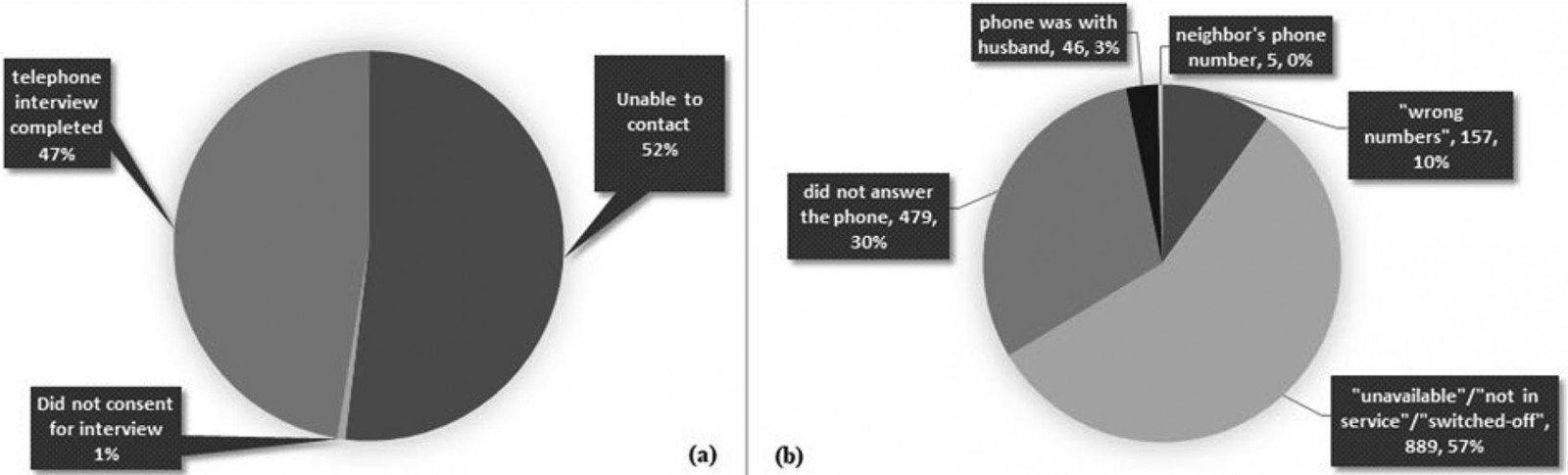

Data for the current analysis were available from 3374 pregnant women with a mean age of 27.9 years (standard deviation (SD) 5.6 years). Mean age of their husbands was 31.9 years (SD 5.9 years). The majority (88.9%) of pregnant women had completed their post-primary education. Of the total sample, 3284 (98.4%) had at least one mobile phone in their households and only 496 (14.7%) had a fixed-access phone. A contact telephone number was provided by 3138 (95.6%) pregnant women. For the telephone interview (6–9 months after the baseline assessment), already reported first-trimester miscarriages were excluded and 3034 (89.9% of baseline participants recruited) were included in the telephone list. During attempts to contact them, 157 (5.2%) were identified as wrong numbers and 889 (29.3%) were unavailable, not in service or switched off in all repeated attempts. Despite several calls, 479 (15.8%) did not answer their phone. On 46 (1.5%) occasions, the phone was answered by the husband of the participant, and he was away from home, and 20 (0.7%) pregnant women answered the phone but were hesitant to provide information. Five (0.16%) of the cellular connections were from neighbors/relatives, which were used only to convey essential messages.

Figure 1 shows that only 47.4% of the participants who were included in the telephone list were actually contactable and also the reasons and distribution of participants who were unable to be contacted through telephones. Of the 3374 initial cohort sample, telephone interviews were completed among 1438 (42.6%). Of these, 476 (33.1%) were using messaging apps, which included WhatsApp, Viber, IMO and Facebook Messenger. A simple comparison (χ2 test) showed (p<0.05) pregnant women and husband with low education levels, and those without easy access to healthcare, were difficult to contact as well as not having access to messaging services.

Figure 1: (a) Distribution of participants by study participation (n=3034). (b) Distribution of non-contactable participants by reason (n=1576).

Figure 1: (a) Distribution of participants by study participation (n=3034). (b) Distribution of non-contactable participants by reason (n=1576).

Discussion

Despite having a push towards use of alternative services for interviews as well as message delivery, this large population-based study showed that, in rural districts, those approaches may be largely invalid. A study carried out in Galle, Sri Lanka and published in 2017 reported a 52% non-respondence7 showing that telephone interview is a challenge even in relatively urban areas. Another island-wide study showed a 62%8 follow-up rate for telephone interviews after a longer interval, such as 4 years, for follow-up. Our study shows that ,in rural settings, long-term follow-up as well as interventions through internet/smart phone-based techniques is still a big challenge. Discussions with public health midwives revealed that predominant use of prepaid services is one reason for not being able to contact these rural participants due to frequent lack of credit. Also, changing mobile numbers is very common among people in these rural settings. A considerable number (15.5%) did not answer the call and it is an established practice by females of this area not to answer calls from unknown phone numbers.

Conclusion

The difference between face-to-face and telephone interviews are well documented in literature3,9. Even though telephone interviews and remote data collection and health promotion methods sound promising during the pandemic, there are still significant barriers for health service delivery in rural settings, and affected people are deprived of proper health promotion services. In addition to data quality and validity, telephone interviews in Sri Lankan rural setting may lead to selection bias, where the sample will be more educated, financially stable and already have better access to health care. If other ways to target vulnerable people in rural areas are not in place, the adoption of a telephone-based strategy for health message delivery may worsen health disparity during the COVID-19 pandemic. These lessons learned will aid in the planning and implementation of research and health promotion initiatives in rural areas of low- and middle-income nations throughout the world.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Professor TC Agampodi, Dr WAND Wickramasinghe, Dr YPJN Warnasekara, Dr DAU Hettiarachchi and Dr GS Amarasinghe for their great support in designing and conducting this study. We also acknowledge the Accelerating Higher Education Expansion and Development (AHEAD) Operation of the Ministry of Higher Education, Sri Lanka which is funded by the World Bank, for funding the original cohort study.

References

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Gestational diabetes in a rural, regional centre in south Western Australia: predictors of risk

2010 - Early childhood caries among Hutterite preschool children in Manitoba, Canada