Context

Australia is a vast country, with approximately 28% of its population living in regional and remote areas1. Access to high quality health care is a well-documented challenge for this population when compared to metropolitan counterparts2. This population typically has higher levels of disease and injury, lives shorter lives, and experiences more challenges in accessing health services, including end-of-life and palliative care3. While regional and remote access to health services is an issue in all Australian jurisdictions, these issues are particularly acute in Western Australia (WA) due to its vast area and population distribution, which comprises many communities with limited access to medical practitioners4.This policy report will focus on regional and remote access in WA, in the context of voluntary assisted dying (VAD).

VAD is a relatively new end-of-life choice that is available to terminally ill competent adults who can satisfy narrow eligibility criteria. The existence of regimes for lawful assisted dying have expanded significantly around the world in the past 20 years5.In Australia, at the time of writing, VAD had been legalised in six states (Victoria, WA, Tasmania, South Australia, Queensland and New South Wales) and has commenced operation in Victoria and WA. While there is some variation across states, the legislative models are broadly similar. The practice is highly regulated, and access is only possible with the approval of at least two medical practitioners who have undertaken the legislatively mandated training and possess the necessary level of qualifications and experience (and, in Victoria and South Australia, one of the medical practitioners must have expertise in the patient’s disease, illness or condition). The VAD substance is dispensed by a pharmacy, and self-administration (by the person) and practitioner administration (by eligible health practitioners) are permitted.

Victoria’s VAD laws, the first VAD laws in Australia, commenced operation in June 2019. One of the practical challenges in Victoria is finding an eligible medical practitioner willing to assist in the VAD process6,7. This challenge is particularly acute for those in regional and remote communities6,8,9. In Victoria, approximately 35% of practitioners are from regional and remote areas, and only a small proportion of them are specialists10. The lack of qualified medical practitioners has often meant terminally ill patients have been forced to travel to metropolitan Melbourne to be assessed. For patients who are too gravely ill to travel, this can mean they are unable to access VAD6.

Under all VAD legislative models, health practitioners can conscientiously object to being involved. The implications of conscientious objection may be disproportionately great for individuals seeking VAD in regional and remote communities due to the already smaller cohort of eligible medical practitioners9,11,12. These communities tend to be disproportionally serviced by internationally trained practitioners13, who have been found to more likely claim a conscientious objection to ‘contentious’ medical practices such as abortion14. Similarly, reputational and community stigma have been found to deter health practitioners from participating in VAD, which is particularly acute in the regional and remote context given practitioners typically live in the same community in which they practise6,9,15.

A further barrier for regional and remote access to VAD is the restriction on the ability of health professionals and patients to communicate through telehealth. This restriction potentially applies in the VAD context because of Commonwealth criminal law, which makes it an offence in some circumstances to discuss ‘suicide’ via a ‘carriage service’ (such as telehealth). While this law was enacted before state VAD laws were passed, and it targeted different activities, it has potentially criminalises certain aspects of the VAD process that are permitted under state VAD laws and causes significant access issues for regional and remote residents 7,10,16-20.

Equity of access to VAD for individuals living in regional and remote communities will be a challenge for any Australian jurisdiction legalising VAD, and states have taken a variety of approaches to mitigate this inequity. However, recognising such challenges would be pronounced in the WA context – due to the state’s geography and population distribution – the WA Government implemented a range of initiatives intended to facilitate access for all potentially eligible individuals to VAD, regardless of where they reside. This policy report explores initiatives used to facilitate regional and remote access in WA, reflecting on the lessons learned and the implications of such initiatives for future implementation of VAD in other Australian jurisdictions and internationally.

Regional and remote access initiatives

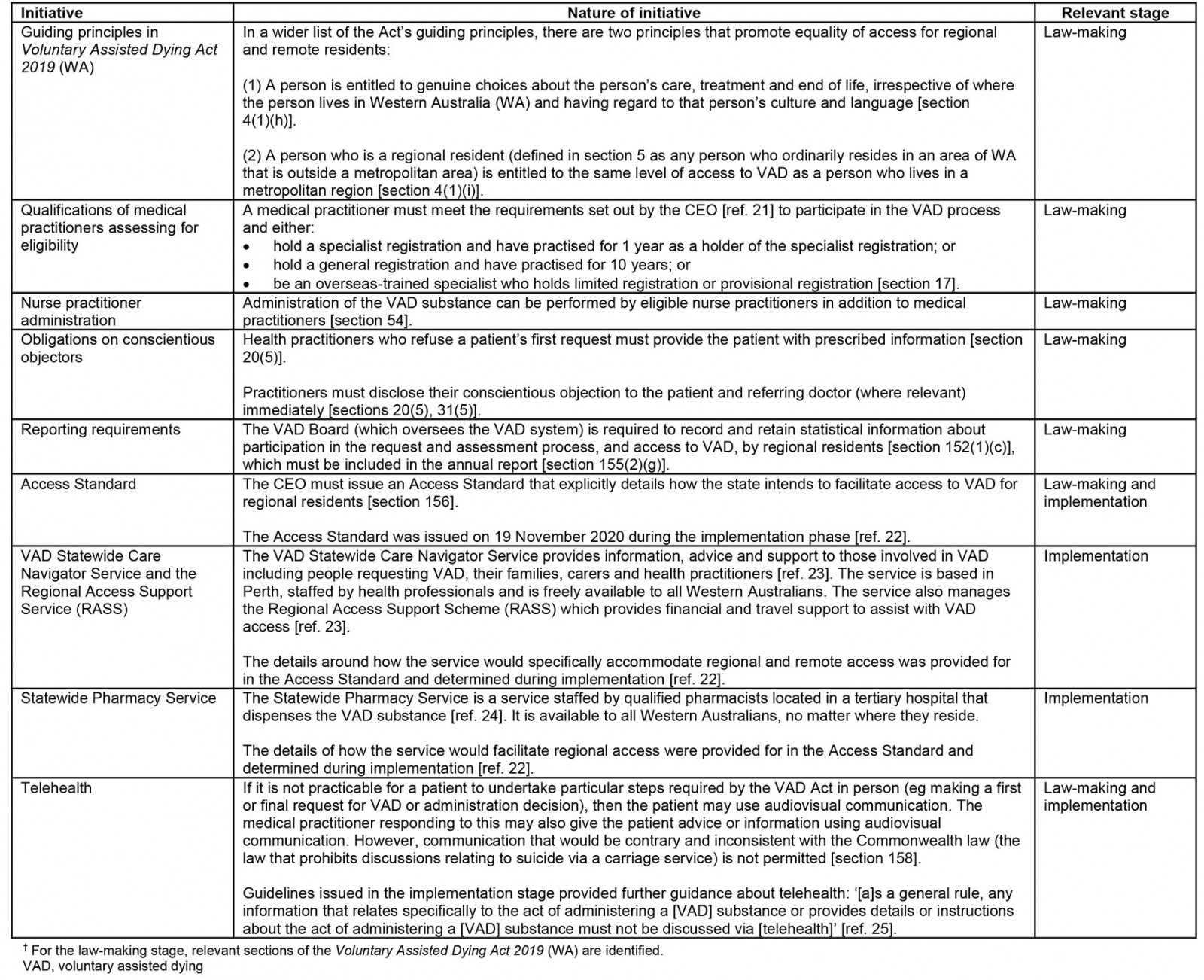

The focus of this policy report is on regional and remote access initiatives that have been identified through four sources: VAD legislation or policy, parliamentary debates, the Ministerial Expert Panel (MEP) report (which advised the WA Government on designing the VAD system)4, and academic literature. These initiatives, identified in Table 1, and described more fully in the commentary that follows, occurred at two different stages of the reform process. The first is the law-making stage (up to 19 December 2019, when the law was passed by Parliament) and the second is the implementation stage (from 19 December 2019 to when the law started in force on 1 July 2021).

Because the WA law began operation in July 2021, the design and implementation phases could draw on early insights from Victoria. However, as was repeatedly noted in the MEP’s report, the vast differences between Victoria and WA, particularly in relation to WA’s geography, population distribution and cultural diversity, demanded further measures to support the needs of regional and remote communities4.

Table 1: Overview of initiatives21-25†

Guiding principles

During the law-making process, dedicated principles to promote equity of access for regional and remote residents were introduced (Table 1). Principle (1) was recommended by the MEP in response to consultation feedback that there should be dedicated guiding principles related to equality of access4. Principle (2) was introduced during the parliamentary debates to acknowledge the government’s commitment to providing regional and remote residents equal access to VAD26.These principles, while not creating specific legal obligations, guide the interpretation of the Act and were relied on to introduce access initiatives for regional and remote residents.

Qualifications of medical practitioners

Due to access concerns about availability of medical practitioners, the MEP recommended that criteria for practitioners to participate in the VAD process be less restrictive than in Victoria4.The MEP suggested that relevant experience and skills of practitioners were more pertinent than specialist qualifications and noted that many senior doctors working in country hospitals did not have specialist qualifications4.The MEP recommended that, unlike in Victoria, the legislation should not require participating practitioners to hold a fellowship from a specialist medical college or be a vocationally trained GP4. Nor did it recommend that at least one of the practitioners have 5 years’ experience post-fellowship or post-registration, or one of the practitioners have relevant expertise and experience in the patient’s disease, illness or condition (also Victorian requirements)4. WA practitioners must still satisfy the legislative requirements (Table 1) to participate in VAD.

Nurse practitioner administration

To increase the pool of clinicians available to administer VAD, the MEP recommended nurse practitioners’ involvement4. By contrast, Victorian law only permits practitioner administration by medical practitioners. The MEP suggested that nurse practitioners’ extensive training and scope of practice would make them suitable to participate in VAD, noting that nurse-led teams already provide specialist palliative care in regional and remote WA4.

Conscientious objection

The MEP considered how conscientious objection could hamper access. While recommending conscientious objection to be permitted, the MEP wanted to ensure that patients were still provided with sufficient information about VAD to ensure access4. The access challenges posed by conscientious objection, particularly in regional and remote communities, are widely recognised9,11,12. Commentators have raised concerns about the Victorian VAD Act’s conscientious objection provision (section 7), and its ability to compound access issues, due to the lack of obligations it imposes on conscientious objectors to refer patients on to willing practitioners or provide information about VAD8,9. WA, unlike Victoria, requires conscientious objectors to provide the patient with standardised information, which includes contact details of the VAD Statewide Care Navigator service and information about regional support packages27.

Statistical information

The Act’s requirement to collect and publish statistical information about regional access was an amendment moved during parliamentary debates. It was reasoned that given the commitment to facilitate equal access for regional and metropolitan residents (guiding principle (2) discussed above), parliament should support this initiative to ascertain to what extent this principle is realised in practice26.

Access Standard

During parliamentary debates, the VAD Bill was amended to introduce an Access Standard, with its content to be determined during implementation. The amendment was moved due to concerns about the access inequities some WA residents face, particularly regional and remote residents26. The Access Standard was intended to assist people seeking VAD to understand how they can do so and reflected the Act’s principles about equitable access26. It was issued in November 2020 and indicated that regional and remote access would be facilitated via the VAD Statewide Care Navigator Service, Regional Access Support Scheme (RASS), VAD Statewide Pharmacy Service and by the state providing clarity about, and monitoring developments in relation to, telehealth22. These specific initiatives are discussed further below.

VAD Statewide Care Navigator Service and Regional Access Support Scheme

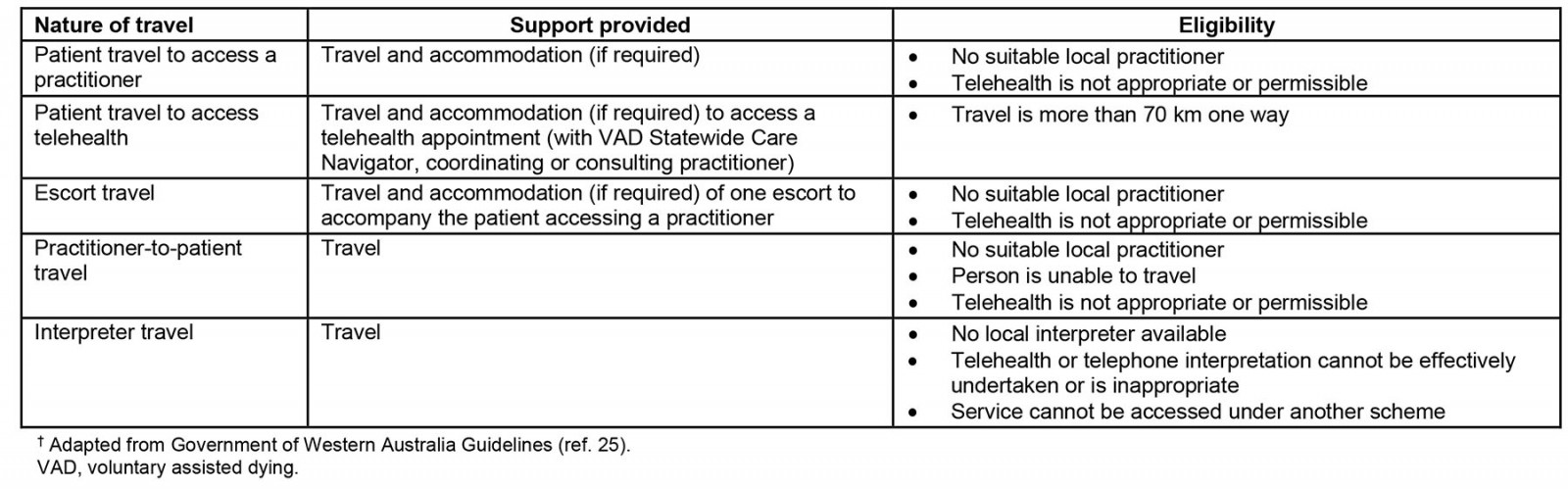

When considering possible access issues, the MEP recommended establishing a VAD Statewide Care Navigator Service4. While the Navigator Service facilitates VAD access statewide, the Access Standard specified that the service would include provision for regional and remote residents to receive information and face-to-face support (if required)22. The Access Standard also established the RASS to facilitate access by supporting persons living in regional and remote areas to travel in order to access a practitioner, or support a practitioner to visit the person through payment of travel expenses and remuneration22. Further detail about the scheme’s travel support is provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Regional Access Support Scheme travel support25†

VAD Statewide Pharmacy Service

Although a Statewide Pharmacy Service was contemplated during the law-making process, its operation was only determined during implementation. In the parliamentary debates, a hub-and-spoke model was considered optimal, with a central pharmacy service at a tertiary hospital with several regional pharmacy hubs26, but was ultimately not adopted. The Access Standard provided that the service would actively engage with regional and remote residents to ensure safe, timely and appropriate supply of the VAD substance and ensure regionally based ‘Authorised Disposers’ could facilitate convenient substance disposal for these residents22. The service has also set (and to date met) 5 days as the key performance indicator for supply of the VAD substance, compared to 2 days for metropolitan WA28.

Telehealth

The MEP’s consultation process revealed some support (albeit not universal) for telehealth to enable regional and remote access to VAD4. The MEP recognised that telehealth already played a significant role in delivering specialist palliative care in regional and remote communities and acknowledged that electronic information exchange would enable reliable and secure access to VAD statewide4. The MEP indicated that access to telehealth would primarily be addressed during implementation, but recommended that there should be no impediment to appropriate use of telehealth in the legislation4.

The importance of telehealth for regional and remote access, and concerns about the impact of the Commonwealth Criminal Code, were raised in the parliamentary debates26. The WA Government indicated that it was in continuing discussions with the Commonwealth and committed to adopting alternative implementation strategies to assist with access if telehealth was not permitted26.

The Access Standard provided that the state would continue to monitor developments in the Commonwealth Criminal Code and provide clarity around what audiovisual communications could be appropriately utilised22. As already discussed, the WA Government issued guidance (via its clinical guidelines) during implementation making it clear that some discussions about VAD should not occur via telehealth25.

Lessons learned

This policy report has considered an existing challenge (regional and remote access to health care) in the context of a new and sensitive end-of-life option, VAD. This report has focused on WA, the jurisdiction to date with the greatest need to address regional and remote access, and one that has taken specific steps to do so.

Currently, there are limited data available about regional and remote access to VAD in WA, given the official report of WA’s VAD operations is yet to be published. However, in June 2022, the WA Minister of Health stated in Parliament that, as of 31 May 2022, there were 68 fully trained medical practitioners eligible to provide VAD, 46 of whom came from Perth (including the Peel region), with the remaining 22 coming from regional and remote areas29. The Minister also indicated that 171 individuals have accessed VAD, 21% of whom were located in regional areas29.The RASS has reportedly been used multiple times to provide access to individuals in regional and remote areas30. Despite its acknowledged usefulness, it has been noted that the lack of local practitioners in regional and remote regions means that residents in these areas face greater burdens30. Incentives such as remuneration for training have been proposed to help increase the number of providers31, and there is emerging evidence that the RASS has been used to partly compensate regional practitioners for undertaking the training to assist a particular patient when there are no trained practitioners available in the area32.

Despite these early indications, it is still unclear how regional and remote access will fare in WA. However, as already noted, there was a considered and targeted focus on regional and remote access in both the law-making and implementation stages of the WA system. Evaluation of the effectiveness of WA’s access initiatives and opportunities to improve will be critical. It is significant that regional and remote access is the subject of legislatively mandated data collection and reporting because this facilitates transparent assessment of progress on this issue. Providing health care generally is challenging for regional and remote residents and VAD should not be expected to be any different. However, careful evaluation can assess the effectiveness of the specific measures employed by the WA Government and identify the need for additional measures, if required.

WA is not the only Australian state with regional and remote challenges – indeed all states have them. Significantly, Queensland and Tasmania (two other states that have passed VAD laws that have not yet started) have the most decentralised populations, with the largest proportion of regional residents in the country33. Alongside South Australia and New South Wales, these states have made efforts to facilitate regional and remote access in their respective legislation and will likely introduce further initiatives during implementation. There is an opportunity for these implementation exercises to benefit from the WA experience as well as international assisted dying regimes where regional and remote access issues have similarly been identified12,34. However, each jurisdiction is different, so any initiative must be adapted to the context in which it will operate.

Importantly, in Australia, some VAD access issues for regional and remote communities are beyond the control of state governments. For instance, VAD systems depend on having sufficient willing and available practitioners. Additionally, restrictions on using telehealth cannot be addressed by state governments and depend on Commonwealth action. Despite the limitations of telehealth, especially in the VAD context, telehealth has traditionally been used to help mitigate access barriers, with a range of different telehealth models being used across regional and remote Australia35. Given the burdens this restriction on telehealth creates in the context of VAD, the Commonwealth should amend its Criminal Code16,17.

Note in proof

Since the acceptance of this article, VAD laws are now also operational in Tasmania, Queensland and South Australia. In November 2022, Western Australia’s Voluntary Assisted Dying Board released its first annual report, which details uptake of VAD requests, including among regional patients (https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Corp/Documents/Health-for/Voluntary-assisted-dying/VAD-Board-Annual-Report-2021-22.pdf). Furthermore, the requirements for remunerating regional practitioners for undertaking VAD training has subsequently been broadened, so its availability is no longer limited to cases where practitioners undertake the training to help a particular patient.

Funding

This research is co-funded by the Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Queensland University of Technology and Ben White’s Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT190100410: Enhancing end-of-life decision-making: Optimal regulation of voluntary assisted dying).

Declared conflicts of interest

The authors disclose that Ben P. White and Lindy Willmott were engaged by the Victorian, WA and Queensland Governments to design and provide the legislatively mandated training in each of these states for medical practitioners (and nurse practitioners and nurses as appropriate) involved in voluntary assisted dying. Casey M. Haining was employed on the Queensland VAD training. Lindy Willmott is a member of the Queensland Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board.

References

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Farewell Ralph McLean - a quiet contributor to rural health

2003 - Evaluation of a rural community-based disability service in Queensland, Australia