Context and issues

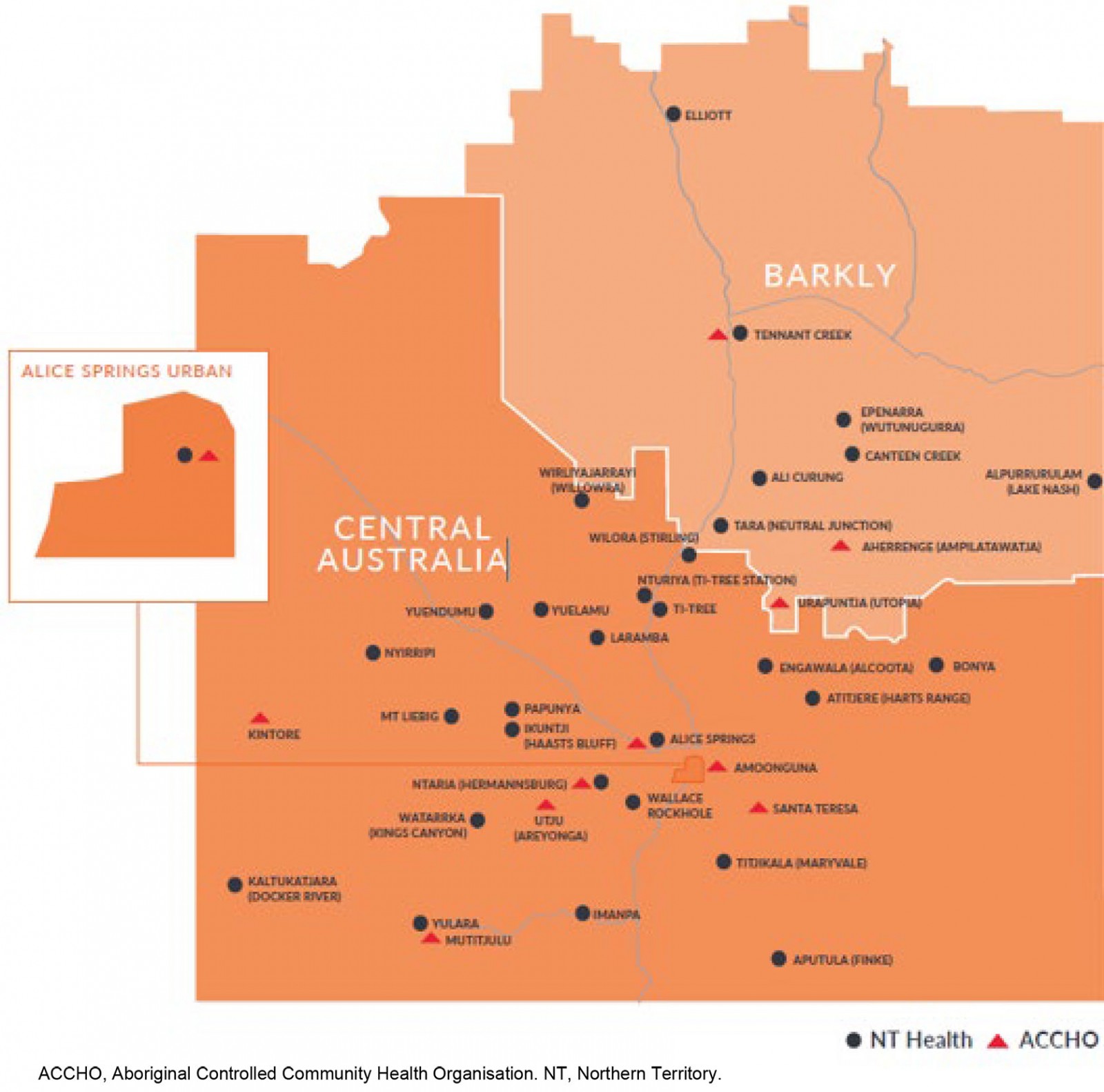

There have been unique challenges in planning for acute care of COVID patients in remote Central Australia. First, there are approximately 15,000 people in 29 remote communities across almost 900 000 square kilometres of the Central and Barkly regions of the Northern Territory (NT), and for most of these communities aeromedical retrieval is the only option for acute care (Fig1). The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) in Alice Springs provides a continuous retrieval service, with two day crews and one night crew, in partnership with Northern Territory Health, as well as a charter crew providing regional community health services.

Second, the baseline sociodemographic of these communities is one of extreme poverty and overcrowded, poor quality housing not amenable to isolation of individuals with infection. Remote health clinics are small and have limited acute care capacity. There are very high rates of comorbidity, which predispose remote community residents to poor outcomes from COVID infection1.

Third, the sociocultural beliefs and expectations of many people in this region are traditional, with a mixed perspective of mainstream health care. As a result, there were relatively low COVID vaccination rates (as low as 20% in some communities) as remote NT cases heralded the beginning of the pandemic in November 20212. For many people in these communities, there is a strong desire to remain at home, regardless of conventional healthcare advice, as interaction with healthcare service providers has a chequered history through which many Elders have themselves lived3. Cultural beliefs of wellbeing are often founded upon being on Country4, a value that has been held onto despite the pandemic.

By January 2022, there was limited experience guiding approaches to remote community outbreaks of COVID. In the outbreak of mid-2021 in north-western New South Wales, the response was recognised to be a dual crisis of pandemic exacerbated by inadequate and overcrowded housing5. In late 2021, as the pandemic took hold in the NT, the initial approach was early detection through wastewater sampling in communities and, if positive, to aggressively test, trace, isolate and quarantine. Entire communities were placed in lockdown to limit community movement and, initially, attempts were made to evacuate all cases to quarantine facilities in urban settings by aeromedical services or as health charter passengers if stable or close contacts. Challenges included an immediate extreme pressure on aeromedical and charter services, stretched quarantine facilities housing people who often had complex comorbidity requiring ready access to primary care, and problematic post-isolation repatriation. On top of this, the issue of consent to be moved from community was vexing, with many people reluctant to leave and unhappy with distant quarantine.

Figure 1: Communities with airstrips in Central and Barkly regions, Northern Territory.

Figure 1: Communities with airstrips in Central and Barkly regions, Northern Territory.

A risk stratified model for COVID care at home in remote communities

Posed with these challenges and a limited evidence base to guide our approach, the NT Health Central Australian Region service (NTHCAR) in partnership with RFDS developed a risk stratification and remote support model for COVID on Country for remote communities. The program was primarily designed around safety while supporting individuals to choose to remain on Country (as opposed to removal to distant quarantine). The approach was also shaped to balance limited retrieval, quarantine and patient transport capacity in and from Alice Springs.

Rather than continuing to retrieve communities to centralised facilities, NTHCAR and RFDS would transition to bringing care to remote communities in addition to a foundation of telehealth support. This proposal was supported in principle and with funding from the Commonwealth of Australia and Alice Springs Hospital.

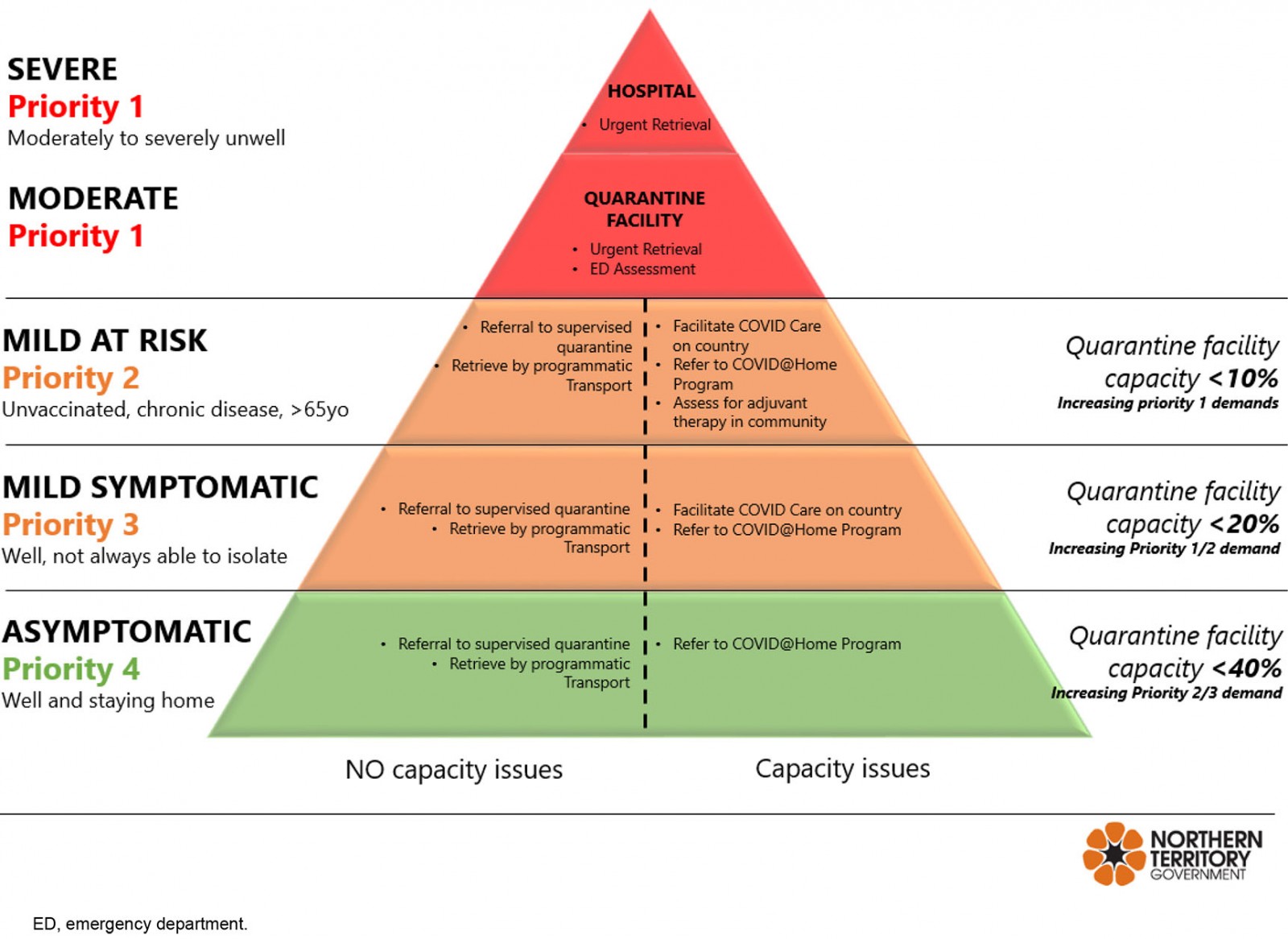

The process was designed to manage limited capacity for transport and quarantine as safely as possible while determining the optimal COVID positive pathway (Fig2). Rather than moving all community cases, NTHCAR transitioned to a schedule of moving clinicians and hospital-level COVID care, including monoclonal antibody infusions and restocking of oral antivirals, to remote communities, with ongoing telehealth monitoring and advice. This model of outpatient care for high risk patients and those with mild to moderate disease has been proposed in the literature, with similar concerns in the USA about delayed access to care for high risk rural populations6, and safe outpatient care has successfully been deployed in emergency departments7, outpatient settings8 and rural communities9.

Thus a COVID on Country model of care for Central Australians was developed between October 2021 and January 2022, and implemented commencing February 2022.

The underlying principle of the NTHCAR model rests on timely assessment of two risk factors: patient factors and community/capacity factors. Prioritisation of care and location were based upon both factors.

Patient factors

Every remote living patient diagnosed in a community underwent risk assessment and stratification for suitability to remain on Country or for aeromedical retrieval, based upon evolving recommendations from the National Covid-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce10. This stratification was Priority 1 (moderate to severely unwell), Priority 2 (mild, but high risk), Priority 3 (mildly symptomatic, but potentially unable to isolate) and Priority 4 (asymptomatic, well and able to stay at home).

Community/capacity factors

Patients were assessed in the context of their community regarding:

- majority of household confirmed or assumed positive

- threshold community incidence above 20%

- majority of community positive and/or recovered from COVID.

Identification of any of the above categories triggered a referral to the COVID on Country program11, with a goal of minimising the risks of system overload of a generic track/trace/transport for isolation approach to the patient in their community.

Current capacity of the quarantine facilities themselves was factored into the disposition of the patient:

- Capacity <40% triggered referral for home monitoring, but plan still to transport for quarantine.

- Capacity <20% triggered additional consideration of COVID on Country.

- Capacity <10% triggered additional consideration of adjuvant care (e.g. monoclonal antibody infusion) in community.

Figure 2: Risk stratification model for COVID on Country.

Figure 2: Risk stratification model for COVID on Country.

Implementation of COVID on Country model

Several principles were prioritised in this model of care.

COVID care in community

Positive cases were registered for the COVID on Country program in community and monitored via a Primary and Public Health Care Remote flow chart. Regular daily reassessment of risk (clinical status including baseline risk factors, pulse oximeter saturation measurements, respiratory rate, pulse rate and blood pressure) ensured accurate restratification and prioritisation for escalation to early community therapy, as well as timely access to supportive care (such as analgesics, oral rehydration salts and haemodynamic monitoring).

Foundation of shared care

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and regular remote primary care teams were actively engaged and consulted for ‘COVID of concern’ patients (priorities 1–3), with clinical support and advice provided by the COVID on Country team.

Programmatic clinician/consumable support and planned retrieval

Up to twice-daily scheduled COVID on Country routes were arranged to cover all regions of Central Australia, with RFDS crews and appropriately trained NTHCAR clinicians carrying doses of the monoclonal antibody treatment sotrovimab to ensure regular in-person support of COVID patients in communities. Cold chain was maintained by the use of Credo CubesTM, maintaining temperatures of 2–6°C without electricity for 36 hours at high ambient temperatures12. Clinical care was sequentially escalated remotely by telehealth, including commencement of inhaled budesonide and/or sotrovimab administration in community. Patients who displayed signs of moderate to severe illness were escalated to aeromedical retrieval to hospital-based care.

Lessons learned

In the first 3 weeks of the program, 485 at-risk patients were successfully monitored remotely, with early intensive review and intervention performed for 203 at-risk patients, including 16 who received monoclonal antibody infusion in community, 29 transferred by charter flight for quarantine or further assessment in Alice Springs, and eight retrieved by RFDS/NTHCAR. There was significant idiosyncratic diversity in the challenges faced (Box 1). This represents both culturally appropriate patient-centred health care and additionally demonstrated significant economic and retrieval resource benefits of fewer unnecessary aeromedical transfers (a retrieval requires a dedicated return flight to a community, and the RMP COVID on Country routes allowed a single aircraft to visit up to eight communities in one loop), and lower facility-based accommodation and repatriation costs.

Challenges were many and varied, and consisted of an amplification of business-as-usual hurdles that remote hospitals deal with every day, superimposed with pandemic conditions. With adequate use of infection control, staffing of the remote clinicians was minimal and none were infected with the virus. There were, however, many disruptions to normal staffing, felt particularly within the hospital system. Subsequently, the reduced demand resulting from maintaining stable patients in their remote communities of origin was beneficial to the larger acute healthcare system. Supply chain disruption was also a major issue as experienced by health services globally throughout the pandemic.

The COVID on Country approach to supporting remote communities in Central Australia has been safely and successfully implemented in a partnered model between NTHCAR, RFDS and the Commonwealth of Australia through clinical pathways, RFDS monoclonal antibody supply chain, and operations/logistical support, providing options for both patient-centred and culturally safe high quality care in community for remote First Nations Australians.

The pandemic has created extreme challenges for healthcare services worldwide and, in the context of the logistical complexities of remote Australia, significant capacity issues were expected when extraordinary measures were implemented at short notice13. For clinicians in Central Australia, clinician–patient continuity relationships are fundamental to provision of conventional health care to First Nations Australians. Many of these pandemic-driven requirements have substantially strained such relationships. Being aware of this at Alice Springs Hospital, the foundations of COVID on country were built upon values of respect, autonomy and consent and we have strived towards culturally safe and high quality care under very challenging circumstances.

Whilst an intermittent face-to-face clinical support underpinned by remote telemedicine is effective, ongoing infrastructure limitations to remote monitoring continue to be barriers to optimal patient safety. Personal access to telehealth may not be universally accessible to remote communities, with one study reporting that only 63% of First Nations Australians have access to internet at home compared with 91% of other Australians14, and recent extreme weather events in Australia have exposed the insecurity of basic phone access for communities15. Thus face-to-face clinical support rises in importance for remote communities in Central Australia.

Potential applications of care in community for remote underserved populations in Australia and other global settings may be similarly cost-effective, whether for outbreaks of infectious disease or where other aetiologies put remote populations at risk of delayed or culturally unsafe care far from home. Successful remote infusions of sotrovimab with close remote support may open the door to conversations about other on-country care, such as chemotherapy and dialysis.

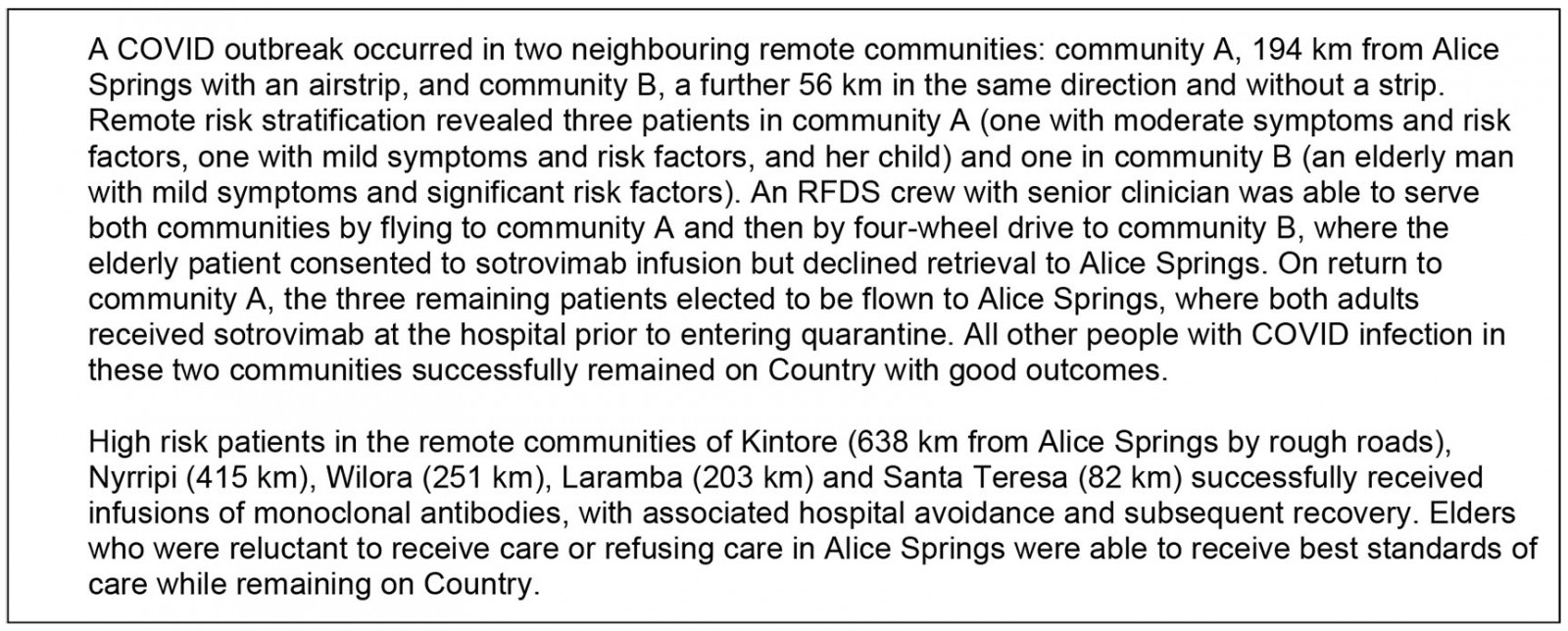

Box 1: COVID care choices in two Central Australian communities, January 2022

Box 1: COVID care choices in two Central Australian communities, January 2022

References

You might also be interested in:

2016 - Can a 'rural day' make a difference to GP shortage across rural Germany?