Introduction

Over the past 20 years, research delineating the nature of nursing practice in rural and remote Canada has emerged and grown1-9. Commensurate with this growing body of knowledge is the translation of research findings into policy and educational programs, as the important relationship between the role of nurses and the health of rural communities is becoming increasingly apparent10-13. Despite the increased understanding of Canadian rural and remote nursing in the past two decades, no nursing frameworks to guide rural and remote practice had been previously synthesized.

This article outlines the initiative of the Canadian Association for Rural and Remote Nursing (CARRN) in 2020 and 2021 to develop a document that will be used to inform the professional practice of all categories of regulated nurses (registered nurses (RNs), licensed practical nurses (LPNs) or registered practical nurses in Ontario (RPNs), registered psychiatric nurses (RPNs) and nurse practitioners (NPs)) working in rural and remote Canada. Founded in 2004, CARRN aims to ‘promote and advance the unique specialty of rural and remote nursing practice through recognition, research and education, and influence rural and remote health policy’14. The CARRN Executive also identified the necessity to revise their previous 2008 discussion document on rural and remote nursing parameters. Both projects began simultaneously in the northern summer of 2020 with funding from the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. Overall coordination of the project was led by the CARRN President (MP), with revision of the updated discussion paper and development of the framework undertaken collaboratively by two consultants (DE, JK). Ongoing discussions and findings from the updated discussion paper15 critically informed work on the practice framework document.

Canadian nurses working in rural and remote areas

Rural areas defined by Statistics Canada have a population density less than 400 persons per square kilometer and fewer than 1000 people16. Based on this definition, the rural population in Canada increased slightly (+0.4%) in 2021 to 6.6 million and accounted for nearly 18% of the Canadian population16. The expanse of the country, as well as its varied rural geography and demographics, pose challenges to healthcare delivery17.

Canadian nurses working in rural and remote regions practice in conditions unique from that of their urban counterparts. Isolation from healthcare specialists and tertiary facilities frequently necessitates the transfer of patients, often in the midst of unpredictable or inclement weather15. Working with an extended scope of practice is not uncommon for nurses in rural and remote Canada18. In contrast to the recent increase in rural population, the number of nurses in rural and remote areas of Canada is shrinking. In 2020, the number of RN, LPN, RPN and NP personnel identified as ‘working rural’ totalled 41 071 nurses, and constituted only 10% of all Canadian nurses employed within the profession19. It is currently unknown whether the mental and emotional strain precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate current nursing shortages20. There is evidence that rural communities exhibited adaptation and coping during the pandemic21,22, yet it remains unclear whether this observed adaptation will influence rural nurse retention.

Existing Canadian rural health frameworks

Provincial and federal governments have produced rural health frameworks over the past ten years. In 2015, British Columbia published a framework document that incorporated a rural policy lens10, and the Ontario government developed a rural and northern healthcare framework/plan in 201723. Some of the guiding principles used to develop these frameworks included community engagement, population health need, shared responsibility, flexibility and innovation, team-based approaches, cultural safety, integration and being evidence-based10-23. Understandably, government frameworks focus on service delivery or quality improvement. While a federal population-level rural framework was developed in 2006, it does not capture the interface between healthcare professionals and rural or remote communities24.

In order to improve efforts to recruit and retain family physicians and other health professionals in rural areas, the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Society for Rural Physicians of Canada co-sponsored a committee to formulate a framework for improved access to rural health care in 201725. The resulting social accountability framework and detailed road map identified five partners necessary to address rural communities’ healthcare needs in Canada: policymakers, health professionals, community, health and education administrators, and universities. The social accountability framework addressed rural health workforce issues but, similar to the federal population-level framework, it did not encapsulate the interconnected realities of practice in rural and remote Canada.

The CARRN project aimed to synthesize existing rural and remote nursing evidence into a framework that would guide practice by nurses and inform the actions of rural communities, other health professionals, educators, policymakers and regulators. It was envisioned that use of the resulting framework could enhance the health of Canadian residents who live in rural and remote areas.

Methods

The process of framework development occurred between July and December 2020 and involved several steps. An external advisory group consisting of 16 members of various provincial regulatory bodies, union and professional associations was established by the CARRN Executive. Further to this, six known rural nursing researchers were invited to participate with the external advisory group and the CARRN Executive to critique the project outcomes at various junctures.

Guiding principles relevant to nursing practice were established by the consultants. These included holistic care, community empowerment, philosophy of primary health care, cooperation and collaboration, determinants of health and the professional practice of all regulated nurses in Canada. Particular attention was given to the determinants of health in the formulation of the document, given the known health disparities that exist in rural and remote areas of the country24,26,27. Health determinants from the First Nations Holistic and Planning Model28, as well as those determinants identified by the Government of Canada29, were incorporated into the final model.

To identify existing international rural nursing models or frameworks, a focused review of international literature was conducted. Electronic database platforms, including ProQuest, the Cumulative Index of Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Medline were searched, with literature limited to English-only articles. Dissertations, grey literature and midwifery references were excluded. The following key search words and BOOLEAN operators were used: (Nurs* OR Nursing) AND (practice OR care OR clinical OR social determinants) AND (rural OR remote OR outpost OR frontier OR outback) AND (framework OR model OR theory OR approach). Articles were considered if they provided either a framework for rural or remote nursing or contained models of rural or remote health. Review of article titles and abstracts for relevancy was completed by both consultants, and the qualifying publications were then read in full to ascertain whether they would be retained for framework development.

Following the identification of relevant articles, key elements and components from each article were tallied into a grid for analysis. These attributes were then categorized, and formed the basis for the construction of model diagrams and narrative description. The initial draft of the document was sent to the reviewers for feedback, and revisions followed.

Results

Literature review results

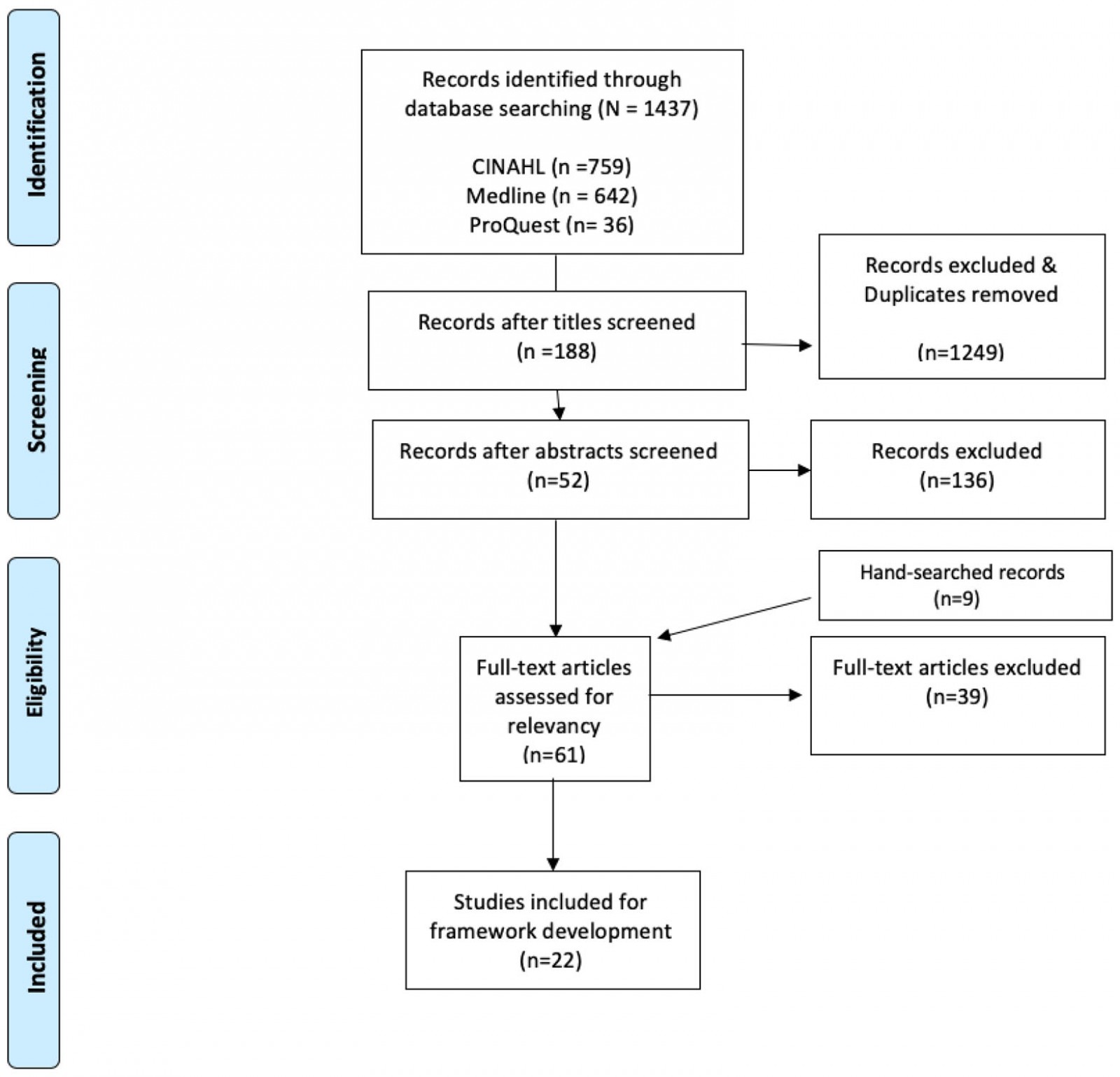

A total of 1437 articles were initially identified from the literature search; after screening titles and abstracts, 52 articles, in addition to nine records found from citations, were assessed for relevancy (n=61). A total of 39 full-text articles were excluded, leaving 22 to be included in the framework development (Fig1). The retained literature, published between 1989 and 2020, originated from five jurisdictions: USA (n=9), Australia (n=6), Canada (n=5), New Zealand (n=1) and South Africa (n=1).

The foci of the publications varied, and included the determinants of health in rural populations30-33, the role of environment and place34-36, concepts related to the development of rural nursing theory37-39, and frameworks for rural nursing leadership40,41. Additional frameworks were multidisciplinary rural professional development42, rural acute care ethical decision-making43, rural health program planning44, primary healthcare logic model45, rural community case management46, and rural and remote health47. Four discussion papers were also among the 22 publications analyzed48-51.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram of literature search, framework development.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram of literature search, framework development.

Process of framework development

Ten components pertaining either to rural health or to rural and remote nursing arose from analysis: community, and importance of participatory engagement (n=11); knowing the rural context (n=8); geography and environment (n=8); determinants of health (n=8); care (n=5); integrated health systems (n=5); ‘being visible’ (eg lack of anonymity, n=4); collaborative communication and teamwork (n=3); social justice and diversity (n=2); and leadership (n=2). Recent Canadian nursing research reports affirmed the importance of understanding the rural context40-43, being part of the community8, being visible52, and coping with geography, weather and travel53.

Numerous characteristics that constitute the ‘complex, generalist practice’8 of the rural or remote nurse’s role in Canada have been identified15. These characteristics include being versatile52, having multiple skills8, expanded practice50, maintaining confidentiality43, being prepared52, providing culturally safe care54 and blurring of professional boundaries43.

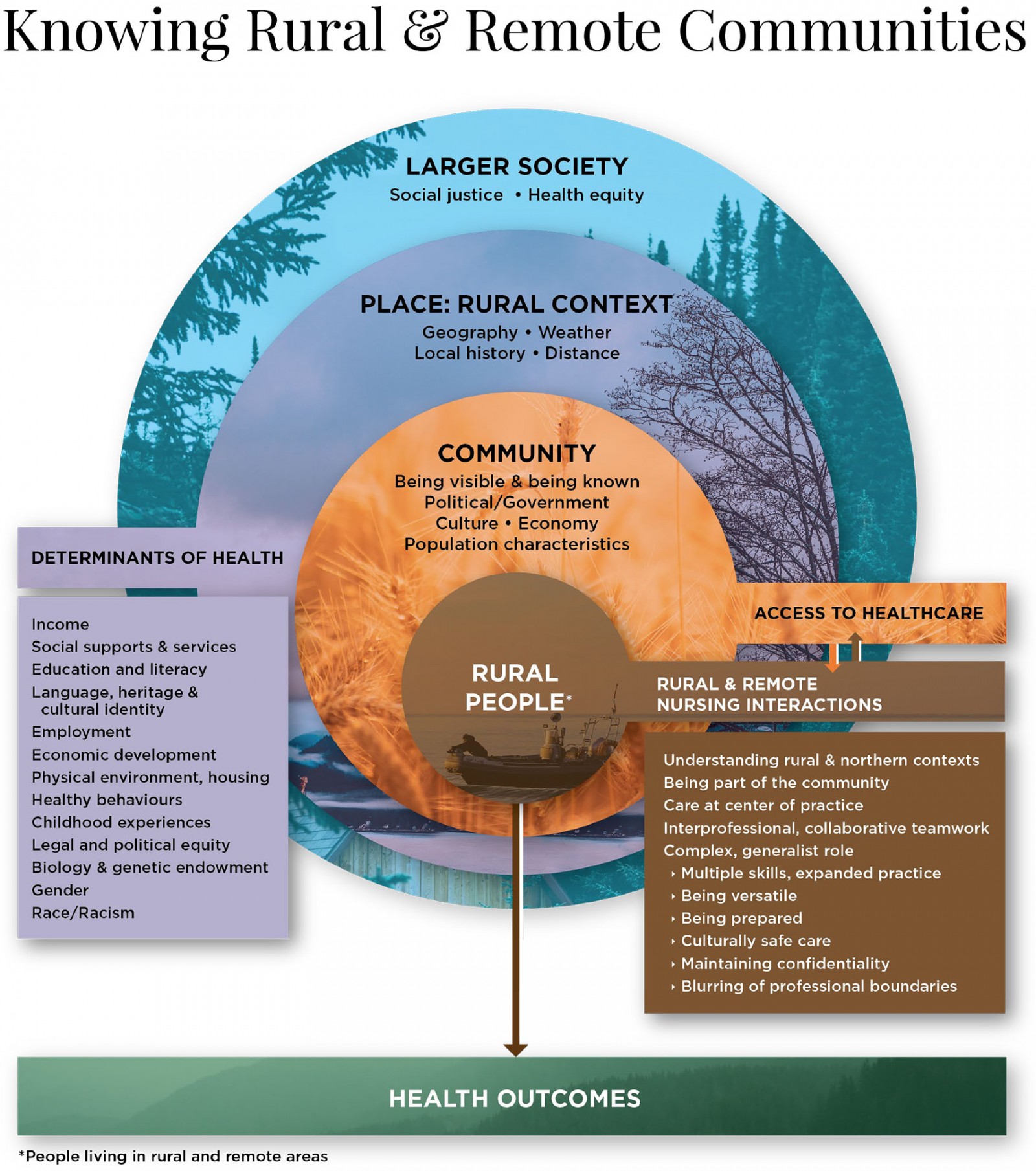

The components and attributes were then synthesized into five main categories: larger society/determinants of health, role of place/the rural or remote context, rural and remote peoples/communities, rural and remote nursing, and health outcomes. Two diagrams, one linear and another circular, were constructed to convey the interconnectedness of the components. The 16-page written document provided background information, definitions of rural and remote, and the process of the framework development, including a descriptive explanation of the framework diagram. To illustrate how the framework could be applied in practice, three clinical exemplars were included in the implications section. Limitations were identified and the document ended with dissemination plans and future actions.

Outcome of framework review and critique

The initial document, the two graphic visualizations drafted by the consultants and a Likert five-point scoring sheet were distributed to all reviewers (n=30) for feedback and critique. The reviewers were from eight provinces and one territory, represented all regulated nurses in Canada, and over half of the reviewers lived in rural or remote regions at the time. The average length of time working in rural or remote practice over their careers was nearly 16 years. Editorial suggestions and detailed comments were incorporated into revisions of the document text. The suggested edits included recommendations for re-organization of content, additional sources and identification of content omissions.

Reviewers were also asked to choose the diagram that best captured the essence of rural and remote nursing practice; a slight majority of reviewers (57%) chose the diagram of overlapping circles, which illustrated an ecologic approach with macro-, meso- and micro-levels of interaction between the framework components. The selected diagram, as well as the reviewers’ comments about the visualizations, were shared with the graphic artist hired for the project. An iterative process of the framework diagram construction occurred between the graphic artist, the consultants and the CARRN Executive and resulted in Figure 2, ‘Knowing Rural & Remote Communities’. In May 2021, the final document was widely disseminated via email to Canadian nursing associations, unions and regulatory bodies.

Figure 2: ‘Knowing Rural & Remote Communities’: a framework for nursing practice in rural and remote Canada.

Figure 2: ‘Knowing Rural & Remote Communities’: a framework for nursing practice in rural and remote Canada.

Final framework diagram

The model consists of four concentric circles, each representing three of the five categories synthesized from the literature. The largest circle encompasses the macro-level values of society at large, including social justice and health equity values. Embedded within the larger circle is the meso-level circle, which represents ‘place’ and the rural context. Geography, weather, distance and local history affect rural and remote places and are intertwined with the determinants of health, shown in the left box. A rural community and its people are the next two layered micro-level circles. Access to health care (a determinant of health) occurs directly at the community level and is found to the right of the community circle. The phrase ‘rural people’ refers to those living in rural and remote areas of Canada. The inner circle encompassing the phrase ‘rural people’ is at the center of the model, surrounded by the influences of local community factors, the rural or remote context and the resulting determinants of health, as well as the larger society. To the right of the inner, foreground circle is the fourth category, that of rural and remote nursing interactions, shaded in the same color as ‘rural people’. Nursing interactions that occur with local rural or remote-living residents all transpire with the same community circle. These interactions are carried out best by knowing and being part of the community50,52. Pertinent attributes of Canadian rural and remote nursing practice are found in the right-hand box below the nursing interactions heading. One identified attribute, collaborative intra- and interprofessional teamwork, is critical for safe functioning of services and the wellbeing of patients8,36,42,55. Health outcomes, the final category of the framework, emerge directly from the combined effects of the larger society, the rural context, determinants of health, the community and interactions with nursing.

In sum, nurses’ attention to the rural context, determinants of health and societal issues assists in better addressing the upstream or root causes56 that affect the downstream health issues observed in daily practice.

Discussion

There is an ever-increasing complexity of delivering health care to rural and remote populations amidst personnel shortages, restricted resources and the COVID-19 pandemic57-59. Such immediate challenges often obscure the larger societal and socioeconomic forces affecting the day-to-day nursing efforts to improve patient health outcomes. As healthcare services only contribute an estimated 25% to the overall health of a population60, health professionals need to collaborate with local rural and remote communities to reduce disparities. Nurses working in these areas must engage with others to advocate for safe and accessible housing, economic stability, clean water, nutritious food, education and social supports. Ideally, practicing nurses will find the framework useful to guide their assessments and strengthen their practice.

Resource and time restrictions of the project prevented consultation with several groups, which is a limitation. Indigenous and Francophone nurses were not part of the framework discussions, nor were community members living in rural or remote Canada. Incorporation of local knowledge40,41, respect for local wisdom and cultural understanding61 by healthcare providers are crucial for shared decision-making with community members. The acceptability of this document among our Indigenous and Francophone nursing colleagues and rural communities remains to be determined through knowledge mobilization efforts by CARRN.

Educational programs or courses that focus on rural and remote nursing practice are limited in Canada. However, content on the determinants of health and the importance of intra- and interprofessional collaboration exists in all Canadian undergraduate nursing curricula. Recent research documented how both collaboration and social determinants of health factored into rural healthcare students’ responses to clinical placements in Alberta, disrupted by the outbreak of COVID-1962. The rural and remote nursing practice framework document has the potential to be incorporated into educational programs with dedicated rural nursing content.

Methods to foster and monitor the uptake of the document are under discussion by the CARRN Executive. Collaborations with researchers to design studies to evaluate and test the use of the framework in practice, education and policy decisions are crucial to advance the scientific knowledge in rural and remote nursing51. Explorations could include testing the proposed linkages in the framework model, examining the effects of the framework content on student learning, as well as determining outcomes of policy decisions.

Conclusion

The resulting framework from this project acknowledges the impact of societal factors on the local community and how nursing and other healthcare professionals’ interactions can improve the health of those living in rural and remote Canada. An opportunity exists to use the framework document to guide rural and remote practice, to impart a structure for nursing students in understanding the rural context, and to inform researchers and policymakers. Scrutiny of the framework by practitioners, educators, researchers and decision-makers is required to determine the overall utility of the framework.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the funding provided by the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. The work could not have been completed without the diligence and work of the CARRN Executive, the external advisory group and our graphic artist, Angela Hot.

References

You might also be interested in:

2017 - Gene therapy renews hope to lower the global rural sickle cell disease burden

2006 - Health and information in Africa: the role of the journal Rural and Remote Health